|

by Dennis Overbye

March 14, 2018

from

NYTimes Website

Spanish version

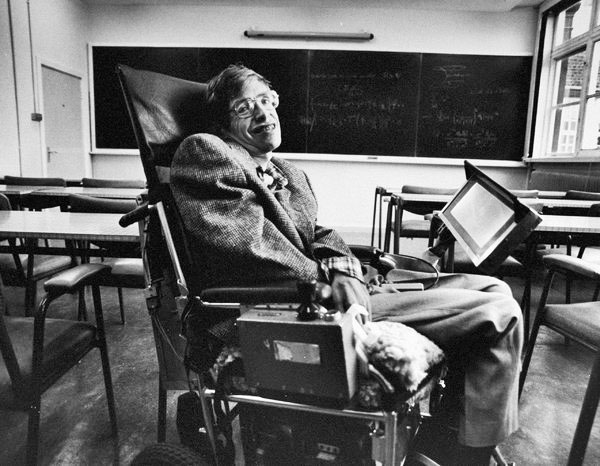

Stephen Hawking became a leader

in

exploring gravity and the properties of black holes.

His

work led to a turning point in the history of modern physics.

Credit

Terry Smith/Time Life Pictures, via Getty Images

A physicist and best-selling

author, Dr. Hawking did not

allow his physical limitations to hinder his quest to answer

"the big question: Where did the universe come from?"

Stephen W. Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist and

best-selling author who roamed the cosmos from a wheelchair,

pondering the nature of gravity and the origin of the universe and

becoming an emblem of human determination and curiosity, died early

Wednesday at his home in Cambridge, England.

He was 76.

A university spokesman confirmed the death.

"Not since Albert

Einstein has a scientist so captured the public imagination and

endeared himself to tens of millions of people around the

world," Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at the

City University of New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Hawking did that

largely through his book "A Brief History of Time - From the Big

Bang to Black Holes," published in 1988. It has sold more than 10

million copies and inspired a documentary film by Errol Morris.

His own story was the

basis of an award-winning 2014 feature film, "The Theory of

Everything." (Eddie Redmayne played Dr. Hawking and won an Academy

Award.)

Stephen Hawking,

one of

the greatest physicists of our time,

died on

Wednesday.

He is

immortalized by his brilliant research,

but

also by his pop culture appearances.

By

CAMILLA SCHICK on Publish Date March 14, 2018.

Photo

by David Parry/Press Association,

via

Associated Press.

Scientifically, Dr. Hawking will be best remembered for a discovery

so strange that it might be expressed in the form of a Zen koan:

When is a black hole

not black? When it explodes.

What is equally amazing

is that he had a career at all.

As a graduate student in

1963, he learned he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a

neuromuscular wasting disease also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

He was given only a few

years to live...

The disease reduced his bodily control to the flexing of a finger

and voluntary eye movements but left his mental faculties untouched.

He went on to become his generation's leader in exploring gravity

and the

properties of black holes, the bottomless gravitational pits

so deep and dense that not even light can escape them.

That work led to a turning point in modern physics, playing itself

out in the closing months of 1973 on the walls of his brain when Dr.

Hawking set out to apply quantum theory, the weird laws that govern

subatomic reality, to black holes.

In a long and daunting

calculation, Dr. Hawking discovered to his befuddlement that black

holes - those mythological avatars of cosmic doom - were not really

black at all.

In fact, he found, they

would eventually fizzle, leaking radiation and particles, and

finally explode and disappear over the eons.

SLIDE SHOW

- Click above image

The Expansive Life of Stephen Hawking

Credit Paul E. Alers/NASA

Nobody, including Dr. Hawking, believed it at first - that particles

could be coming out of a black hole.

"I wasn't looking for

them at all," he recalled in 1978. "I merely tripped over them.

I was rather annoyed."

That calculation, in a

thesis published in 1974 in the journal Nature under the title

"Black Hole Explosions?," is hailed by scientists as the first great

landmark in the struggle to find a single theory of nature - to

connect gravity and quantum mechanics, those warring descriptions of

the large and the small, to explain a universe that seems stranger

than anybody had thought.

The discovery of

Hawking radiation, as it is known, turned black

holes upside down.

It transformed them from destroyers to creators -

or at least to recyclers - and wrenched the dream of a final theory

in a strange, new direction.

"You can ask what

will happen to someone who jumps into a black hole," Dr. Hawking

said in 1978. "I certainly don't think he will survive it."

"On the other hand," he added, "if we send someone off to jump

into a black hole, neither he nor his constituent atoms will

come back, but his mass energy will come back.

Maybe that

applies to the whole universe."

Dennis W. Sciama,

a cosmologist and Dr. Hawking's thesis adviser at Cambridge, called

Hawking's thesis in Nature,

"the most beautiful

paper in the history of physics."

Edward Witten, a

theorist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, said:

"Trying to understand

Hawking's discovery better has been a source of much fresh

thinking for almost 40 years now, and we are probably still far

from fully coming to grips with it. It still feels new."

In 2002, Dr. Hawking said

he wanted the formula for Hawking radiation to be engraved on his

tombstone.

He was a man who pushed the limits - in his intellectual life, to be

sure, but also in his professional and personal lives.

-

traveled the

globe to scientific meetings, visiting every continent,

including Antarctica

-

wrote

best-selling books about his work

-

married twice

-

fathered three

children

-

was not above

appearing on "The Simpsons," "Star Trek: The Next

Generation" or "The Big Bang Theory"

He celebrated his 60th

birthday by going up in a hot-air balloon.

The same week, he also

crashed his electric-powered wheelchair while speeding around a

corner in Cambridge, breaking his leg.

In April 2007, a few months after his 65th birthday, he

took part in a zero-gravity flight aboard a specially equipped

Boeing 727, a padded aircraft that flies a roller-coaster trajectory

to produce fleeting periods of weightlessness.

It was a prelude to a

hoped-for trip to space with Richard Branson's Virgin

Galactic company aboard

SpaceShipTwo.

Asked why he took such risks, Dr. Hawking said,

"I want to show that

people need not be limited by physical handicaps as long as they

are not disabled in spirit."

Dr. Hawking

pushed

the limits in his professional and personal life.

At 65,

he took part in a zero-gravity flight

aboard

a plane that flies a roller-coaster trajectory

to

produce fleeting periods of weightlessness.

Credit

Steve Boxall/Zero Gravity Corporation

His own spirit left many in awe.

"What a triumph his

life has been," said Martin Rees, a Cambridge University

cosmologist, the astronomer royal of England and Dr. Hawking's

longtime colleague.

"His name will live

in the annals of science; millions have had their cosmic

horizons widened by his best-selling books; and even more,

around the world, have been inspired by a unique example of

achievement against all the odds - a manifestation of amazing

willpower and determination."

Studies Came

Easy

Stephen William Hawking was born in Oxford, England, on Jan.

8, 1942 - 300 years to the day, he liked to point out, after the

death of Galileo, who had begun the study of gravity.

His mother, the former

Isobel Walker, had gone to Oxford to avoid the bombs that fell

nightly during the Blitz of London.

His father, Frank

Hawking, was a prominent research biologist.

The oldest of four children, Stephen was a mediocre student at St.

Albans School in London, though his innate brilliance was recognized

by some classmates and teachers.

Later, at University College, Oxford, he found his studies in

mathematics and physics so easy that he rarely consulted a book or

took notes. He got by with a thousand hours of work in three years,

or one hour a day, he estimated.

"Nothing seemed worth

making an effort for," he said.

The only subject he found

exciting was cosmology because, he said, it dealt with,

"the big question:

Where did the universe come from?"

He moved to Cambridge

upon his graduation from Oxford.

Before he could begin his

research, however, he was stricken by what his research adviser, Dr.

Sciama, came to call "that terrible thing."

The young Hawking had been experiencing occasional weakness and

falling spells for several years. Shortly after his 21st birthday,

in 1963, doctors told him that he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

They gave him less than three years to live...

His first response was severe depression. He dreamed he was going to

be executed, he said.

Then, against all odds,

the disease appeared to stabilize. Though he was slowly losing

control of his muscles, he was still able to walk short distances

and perform simple tasks, though laboriously, like dressing and

undressing.

He felt a new sense of

purpose.

"When you are faced

with the possibility of an early death," he recalled, "it makes

you realize that life is worth living and that there are a lot

of things you want to do."

In 1965, he married

Jane Wilde, a student of linguistics.

Now, by his own account,

he not only had "something to live for"; he also had to find a job,

which gave him an incentive to work seriously toward his doctorate.

His illness, however, had robbed him of the ability to write down

the long chains of equations that are the tools of the cosmologist's

trade.

Characteristically, he

turned this handicap into a strength, gathering his energies for

daring leaps of thought, which, in his later years, he often left

for others to codify in proper mathematical language.

Dr. Hawking

and his first wife,

the former Jane

Wilde, in 1990.

The couple married in

1965.

He said the marriage

gave him "something to live for."

Credit David

Montgomery/Getty Images

"People have the

mistaken impression that mathematics is just equations," Dr.

Hawking said. "In fact, equations are just the boring part of

mathematics."

By necessity, he

concentrated on problems that could be attacked through "pictures

and diagrams," adopting geometric techniques that had been devised

in the early 1960s by the mathematician Roger Penrose and a

fellow Cambridge colleague, Brandon Carter, to study general

relativity, Einstein's theory of gravity.

Black holes are a natural prediction of that theory, which explains

how mass and energy "curve" space, the way a sleeping person causes

a mattress to sag.

Light rays will bend as

they traverse a gravitational field, just as a marble rolling on the

sagging mattress will follow an arc around the sleeper.

Too much mass or energy in one spot could cause space to sag without

end; an object that was dense enough, like a massive collapsing

star, could wrap space around itself like a magician's cloak and

disappear, shrinking inside to a point of infinite density called

a

singularity, a cosmic dead end, where the known laws of physics

would break down:

a

black hole.

Einstein himself thought this was absurd when the possibility was

pointed out to him.

Dr. Hawking in his office

at the

University of Cambridge in December 2011.

His

only complaint about his speech synthesizer,

which

was manufactured in California,

was

that it gave him an American accent.

Credit

Sarah Lee/London Science Museum,

via

Agence France-Presse - Getty Images

Using the

Hubble Space Telescope and other sophisticated tools of

observation and analysis, however, astronomers have identified

hundreds of objects that are too massive and dark to be anything but

black holes, including a

supermassive one at the center of the Milky

Way.

According to current

theory, the universe should contain billions more.

As part of his Ph.D. thesis in 1966, Dr. Hawking showed that when

you ran the film of the expanding universe backward, you would find

that such a singularity had to have existed sometime in cosmic

history; space and time, that is, must have had a beginning.

He, Dr. Penrose and a

rotating cast of colleagues published a series of theorems about the

behavior of black holes and the dire fate of anything caught in

them.

A Calculation in His

Head

Dr. Hawking's signature breakthrough resulted from a feud with the

Israeli theoretical physicist Jacob Bekenstein, then a

Princeton graduate student, about whether black holes could be said

to have entropy, a thermodynamic measure of disorder.

Dr. Bekenstein said they

could, pointing out a close analogy between the laws that Dr.

Hawking and his colleagues had derived for black holes and the

laws

of thermodynamics.

Dr. Hawking said no. To have entropy, a black hole would have to

have a temperature. But warm objects, from a forehead to a star,

radiate a mixture of electromagnetic radiation, depending on their

exact temperatures.

Nothing could escape a

black hole, and so its temperature had to be zero.

"I was very down on

Bekenstein," Dr. Hawking recalled.

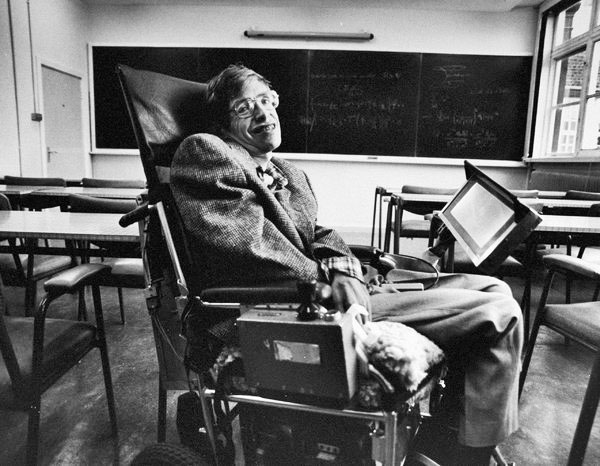

Dr. Hawking in 1979.

The

only subject at University College, Oxford,

that he

found exciting was cosmology because

it

dealt with what he called

"the

big question: Where did the universe come from?"

Credit

Santi Visalli/Getty Images

To settle the question, Dr. Hawking decided to investigate the

properties of

atom-size black holes.

This, however, required

adding

quantum mechanics, the paradoxical rules of the atomic and

subatomic world, to gravity, a feat that had never been

accomplished. Friends turned the pages of quantum theory textbooks

as Dr. Hawking sat motionless staring at them for months.

They wondered if he was

finally in over his head.

When he eventually succeeded in doing the calculation in his head,

it indicated to his surprise that particles and radiation were

spewing out of black holes. Dr. Hawking became convinced that his

calculation was correct when he realized that the outgoing radiation

would have a thermal spectrum characteristic of the heat radiated by

any warm body, from a star to a fevered forehead.

Dr. Bekenstein had

been right.

Dr. Hawking even figured out a way to explain how particles might

escape a black hole.

According to quantum

principles, the space near a black hole would be teeming with

"virtual" particles that would flash into existence in matched

particle-and-antiparticle pairs - like electrons and their evil twin

opposites, positrons - out of energy borrowed from the hole's

intense gravitational field.

They would then meet and annihilate each other in a flash of energy,

repaying the debt for their brief existence.

But if one of the pair

fell into the black hole, the other one would be free to wander away

and become real. It would appear to be coming from the black hole

and taking energy away from it.

But those, he cautioned, were just words. The truth was in the math.

"The most important

thing about Hawking radiation is that it shows that the black

hole is not cut off from the rest of the universe," Dr. Hawking

said.

It also meant that black

holes had a temperature and had

entropy.

In thermodynamics,

entropy is a measure of wasted heat. But it is also a measure of the

amount of information - the number of bits - needed to describe what

is in a black hole.

Curiously, the number of

bits is proportional to the black hole's surface area, not its

volume, meaning that the amount of information you could stuff into

a black hole is limited by its area, not, as one might think, its

volume.

That result has become a

litmus test for string theory and other

pretenders to a theory of quantum gravity. It has also led to

speculations that we live in

a holographic universe, in which

three-dimensional space is some kind of illusion.

Andrew Strominger, a Harvard string theorist, said of the

holographic theory,

"If it's really true,

it's a deep and beautiful property of our universe - but not an

obvious one."

To 'Know the

Mind of God'

The discovery of black hole radiation also led to a 30-year

controversy over the fate of things that had fallen into a black

hole.

Dr. Hawking initially said that detailed information about whatever

had fallen in would be lost forever because the particles coming out

would be completely random, erasing whatever patterns had been

present when they first fell in.

Paraphrasing Einstein's

complaint about the randomness inherent in quantum mechanics, Dr.

Hawking said,

"God not only plays

dice with the universe, but sometimes throws them where they

can't be seen."

Many particle physicists

protested that this violated a tenet of quantum physics, which says

that knowledge is always preserved and can be retrieved.

Leonard Susskind,

a Stanford physicist who carried on the argument for decades, said,

"Stephen correctly

understood that if this was true, it would lead to the downfall

of much of 20th-century physics."

On another occasion, he

characterized Dr. Hawking to his face as,

"one of the most

obstinate people in the world; no, he is the most infuriating

person in the universe." Dr. Hawking grinned.

Dr. Hawking admitted

defeat in 2004. Whatever information goes into a black hole will

come back out when it explodes.

One consequence, he noted

sadly, was that one could not use black holes to escape to another

universe.

"I'm sorry to

disappoint science fiction fans," he said.

Despite his concession,

however, the information paradox, as it is known, has become one of

the hottest topics in theoretical physics. Physicists say they still

do not know how information gets in or out of black holes.

Raphael Bousso of the University of California, Berkeley, and

a former student of Dr. Hawking's, said the present debate had

raised,

"by another few

notches" his estimation of the "stupendous magnitude" of Dr.

Hawking's original discovery.

In 1974, Dr. Hawking was

elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, the world's oldest

scientific organization; in 1979, he was appointed to the

Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge, a post once held by

Isaac Newton.

"They say it's

Newton's chair, but obviously it's been changed," he liked to

quip.

Dr. Hawking also made

yearly visits to the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena,

which became like a second home.

In 2008, he joined the

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, as

a visiting researcher.

Having conquered black holes, Dr. Hawking set his sights on the

origin of the universe and on eliminating that pesky singularity at

the beginning of time from models of cosmology.

If the laws of physics

could break down there, they could break down everywhere.

In a meeting at the Vatican in 1982, he suggested that in the final

theory there should be no place or time when the laws broke down,

even at the beginning. He called the notion the "no boundary"

proposal.

With James Hartle of the Institute for Theoretical Physics in

Santa Barbara, Calif., Dr. Hawking envisioned the history of the

universe as a sphere like the Earth. Cosmic time corresponds to

latitude, starting with zero at the North Pole and progressing

southward.

Although time started there, the North Pole was nothing special; the

same laws applied there as everywhere else.

Asking what happened

before the Big Bang, Dr. Hawking said, was like asking what was a

mile north of the North Pole - it was not any place, or any time.

By then,

string theory, which claimed finally to explain both

gravity and the other forces and particles of nature as tiny

microscopically vibrating strings, like notes on a violin, was the

leading candidate for a "theory of everything."

In "A Brief History of Time," Dr. Hawking concluded that,

"if we do discover a

complete theory" of the universe, "it should in time be

understandable in broad principle by everyone, not just a few

scientists."

He added,

"Then we shall all,

philosophers, scientists and just ordinary people, be able to

take part in the discussion of why it is that we and the

universe exist."

"If we find the answer to that," he continued, "it would be the

ultimate triumph of human reason - for then we would know the

mind of God."

"I want to show that

people need not be

limited by physical

handicaps as long as they

are not disabled in spirit."

Dr.

Hawking

Until 1974, Dr. Hawking was still able to feed himself and to get in

and out of bed.

At Jane's insistence, he

would drag himself, hand over hand, up the stairs to the bedroom in

his Cambridge home every night, in an effort to preserve his

remaining muscle tone.

After 1980, care was supplemented by nurses.

Dr. Hawking retained some control over his speech up to 1985. But on

a trip to Switzerland, he came down with pneumonia. The doctors

asked Jane if she wanted his life support turned off, but she said

no.

To save his life, doctors

inserted a breathing tube. He survived, but his voice was

permanently silenced.

Speaking With

the Eyes

It appeared for a time that he would be able to communicate only by

pointing at letters on an alphabet board.

But when a computer

expert, Walter Woltosz, heard about Dr. Hawking's condition,

he offered him a program he had written called

Equalizer.

By

clicking a switch with his still-functioning fingers, Dr. Hawking

was able to browse through menus that contained all the letters and

more than 2,500 words.

Word by word - and when necessary, letter by letter - he could build

up sentences on the computer screen and send them to a speech

synthesizer that vocalized for him.

The entire apparatus was

fitted to his motorized wheelchair.

Even when too weak to move a finger, he communicated through the

computer by way of an infrared beam, which he activated by twitching

his right cheek or blinking his eye. The system was expanded to

allow him to open and close the doors in his office and to use the

telephone and internet without aid.

Although he averaged fewer than 15 words per minute, Dr. Hawking

found he could speak through the computer better than he had before

losing his voice.

His only complaint, he

confided, was that the speech synthesizer, manufactured in

California, gave him a new vocal inflection.

"Please pardon my

American accent," he used to say.

His decision to write "A

Brief History of Time" was prompted, he said, by a desire to share

his excitement about,

"the discoveries that

have been made about the universe" with "the public that paid

for the research."

He wanted to make the

ideas so accessible that the book would be sold in airports.

He also hoped to earn enough to pay for his children's education. He

did. The book's extraordinary success made him wealthy, a hero to

disabled people everywhere and even more famous.

The news media followed his movements and activities over the years,

from visiting the White House to meeting the Dallas Cowboys

cheerleaders, and reported his opinions on everything from national

health care (socialized medicine in England had kept him alive) to

communicating with extraterrestrials (maybe not a good idea, he

said), as if he were a rolling Delphic Oracle.

Asked by New Scientist magazine what he thought about most, Dr.

Hawking answered:

"Women. They are a

complete mystery."

The Academy Award-winning director James Marsh

discusses his newest project, "The Theory of Everything,"

which chronicles the life of the cosmologist Stephen Hawking.

By Carrie Halperin on Publish Date October 27, 2014.

Photo by Liam Daniel/Focus Features.

In 1990, Dr. Hawking and his wife separated after 25 years of

marriage; Jane Hawking wrote about their years together in two

books,

The latter became the

basis of the movie "The Theory of Everything."

In 1995, he married Elaine Mason, a nurse who had cared for

him since his bout of pneumonia. She had been married to David

Mason, the engineer who had attached Dr. Hawking's speech

synthesizer to his wheelchair.

In 2004, British newspapers reported that the Cambridge police were

investigating allegations that Elaine had abused Dr. Hawking, but no

charges were filed, and Dr. Hawking denied the accusations.

They later divorced...

Dr. Hawking married Elaine Mason in 1995.

Credit

Lynne Sladky/Associated Press

His survivors include his children, Robert, Lucy and Tim, and three

grandchildren.

'There Is No

Heaven'

Among his many honors, Dr. Hawking was named a commander of the

British Empire in 1982. In the summer of 2012, he had a star role in

the opening of the Paralympics Games in London.

The only thing lacking

was the Nobel Prize, and his explanation for this was

characteristically pithy:

"The Nobel is given

only for theoretical work that has been confirmed by

observation. It is very, very difficult to observe the things I

have worked on."

Dr. Hawking was a strong

advocate of space exploration, saying it was essential to the

long-term survival of the human race.

"Life on Earth is at

the ever-increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster, such

as sudden global nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus or

other dangers we have not yet thought of," he told an audience

in Hong Kong in 2007.

Nothing raised as much

furor, however, as his increasingly scathing remarks

about religion.

One attraction of the

no-boundary proposal for Dr. Hawking was that there was no need to

appeal to anything outside the universe, like God, to explain how it

began.

In "A Brief History of Time," he had referred to the "mind of God,"

but in "The Grand Design," a 2011 book he wrote with Leonard

Mlodinow, he was more bleak about religion.

"It is not necessary

to invoke God to light the blue touch paper," he wrote,

referring to the British term for a firecracker fuse, "and set

the universe going."

He went further that

year,

telling The Guardian:

"I regard the brain

as a computer which will stop working when its components fail.

There is no heaven or afterlife for broken-down computers; that

is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark."

Dr. Hawking saw space exploration

as

essential to the long-term survival of the human race.

"Life on Earth is at the ever-increasing risk

of being wiped out by a disaster,

such as sudden global nuclear war," he said in 2007.

Credit David Silverman/Getty Images

Having spent the best part of his life grappling with black holes

and cosmic doom, Dr. Hawking had no fear of the dark.

"They're named black

holes because they are related to human fears of being destroyed

or gobbled up," he once told an interviewer.

"I don't have fears

of being thrown into them. I understand them. I feel in a sense

that I am their master."

|