|

In Paris in 1876 a 31-year-old banker named Albert took an 18-year-old named Bettina as his wife.

Both were Rothschilds, and they were cousins. According to conventional notions about inbreeding, their marriage ought to have been a prescription for infertility and enfeeblement.

Despite his own limited gene pool, Albert, for instance, was an outdoorsman and the seventh person ever to climb the Matterhorn.

The American du Ponts practiced the same strategy of cousin marriage for a century. Charles Darwin, the grandchild of first cousins, married a first cousin. So did Albert Einstein.

In the United States they are deemed such a threat to mental health that 31 states have outlawed first-cousin marriages. This phobia is distinctly American, a heritage of early evolutionists with misguided notions about the upward march of human societies.

Their fear was that cousin marriages would cause us to breed our way back to frontier savagery - or worse.

So when a team of scientists led by Robin L. Bennett, a genetic counselor at the University of Washington and the president of the National Society of Genetic Counselors, announced that cousin marriages are not significantly riskier than any other marriage, it made the front page of The New York Times.

The study (Genetic Counseling and Screening of Consanguineous Couples and Their Offspring - Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors), published in the Journal of Genetic Counseling last year, determined that children of first cousins face about a 2 to 3 percent higher risk of birth defects than the population at large.

To put it another way, first-cousin marriages entail roughly the same increased risk of abnormality that a woman undertakes when she gives birth at 41 rather than at 30.

Banning cousin marriages makes about as much sense, critics argue, as trying to ban childbearing by older women.

Inbreeding is also commonplace in the natural world, and contrary to our expectations, some biologists argue that this can be a very good thing.

It depends in part on the

degree of inbreeding.

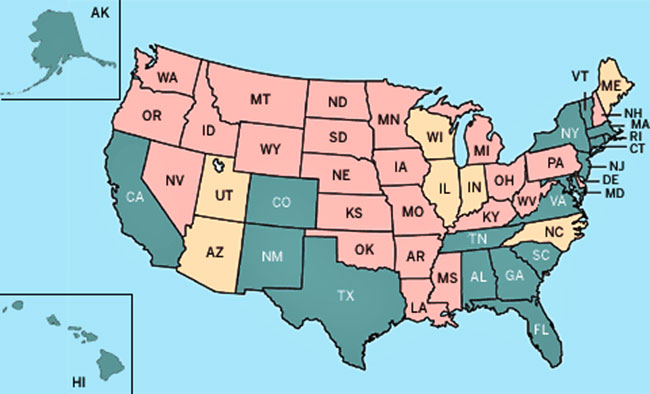

In 24 states (pink), such marriages are illegal. In 19 states (green), first cousins are permitted to wed. Seven states (peach) allow first-cousin marriage but with conditions.

Maine, for instance, requires genetic counseling; some states say yes only if one partner is sterile. North Carolina prohibits marriage only for double first cousins.

Got that?

Map by Matt Zang

So it's important to acknowledge first that inbreeding can sometimes also go horribly wrong - and in ways that, at first glance, make our stereotypes about cousin marriage seem completely correct.

Cousin marriages have been customary in Kashmir for generations, and more than 85 percent of Bradford's Pakistanis marry their cousins. Local doctors are seeing sharp spikes in the number of children with serious genetic disabilities, and each case is its own poignant tragedy.

One couple was recently raising two apparently healthy children. Then, when they were 5 and 7, both were diagnosed with neural degenerative disease in the same week.

The children are now slowly dying. Neural degenerative diseases are eight times more common in Bradford than in the rest of the United Kingdom.

These so-called lethal recessives are associated with diseases like cystic fibrosis and sickle-cell anemia.

The traditional view of human inbreeding was that we did it, in essence, because we could not get the car on Saturday night.

Until the past century, families tended to remain in the same area for generations, and men typically went courting no more than about five miles from home - the distance they could walk out and back on their day off from work.

As a result, according to

Robin Fox, a professor of anthropology at Rutgers University,

it's likely that 80 percent of all marriages in history have been

between second cousins or closer.

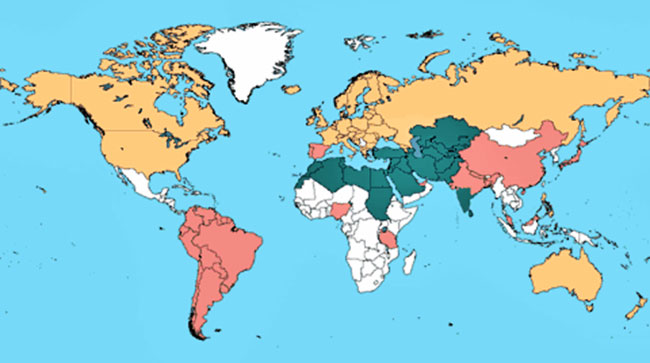

Map by Matt Zang

Pierre-Samuel du Pont, founder of an American dynasty that believed in inbreeding, hinted at these factors when he told his family:

He got his wish, with seven cousin marriages in the family during the 19th century.

Mayer Amschel Rothschild, founder of the banking family, likewise arranged his affairs so that cousin marriages among his descendants were inevitable.

His will barred female descendants from any direct inheritance.

Without an inheritance, female Rothschilds had few possible marriage partners of the same religion and suitable economic and social stature - except other Rothschilds. Rothschild brides bound the family together. Four of Mayer's granddaughters married grandsons, and one married her uncle.

These were hardly people whose mate choice was limited by the distance they could walk on their day off.

Moderate inbreeding may also produce biological benefits.

Contrary to lore, cousin marriages may do even better than ordinary marriages by the standard Darwinian measure of success, which is reproduction.

A 1960 study of first-cousin marriages in 19th-century England done by C. D. Darlington, a geneticist at Oxford University, found that inbred couples produced twice as many great-grandchildren as did their outbred counterparts.

In a family that had not inbred, the same children would have 38 ancestors.

Because of inbreeding, they were directly descended no fewer than six times each from Mayer and Gutle Rothschild.

If our subconscious Darwinian agenda is to get as much of our genome as possible into future generations, then inbreeding clearly provided a genetic benefit for Mayer and Gutle.

The consequences of inbreeding are unpredictable and depend largely on what biologists call the founder effect:

A founding couple can also pass on advantageous genes.

Among animal populations, generations of inbreeding frequently lead to the development of co-adapted gene complexes, suites of genetic traits that tend to be inherited together.

These traits may confer special adaptations to a local environment, like resistance to disease.

Alan Bittles, a professor of human biology at Edith Cowan University in Australia, points out that there's a dearth of data on the subject of genetic disadvantages too.

Not until some rare disorder crops up in a place like Bradford do doctors even notice intermarriage. Something disturbingly eugenic about the idea of better-families-through-inbreeding also causes researchers to look away.

Oxford historian Niall Ferguson, author of The House of Rothschild, speculates that that there may have been,

But he quickly dismisses this as "unlikely."

When we want a dog with the points to take Best in Show at Madison Square Garden, we often get it by taking individuals displaying the desired traits and "breeding them back" with their close kin.

The dominant male in each colony typically inbreeds with his kin. His genes rapidly spread through the colony - the founder effect again - and each colony thus becomes a little different from the others, with double recessives proliferating for both good and ill effects.

When the weather changes or some deadly virus blows through, one colony may end up better adapted to the new circumstances than the other nine, which die out.

Inbreeding, with its

cascade of double recessives, causes the trait to be expressed in

every generation of this family - and under the intense selective

pressure of DDT, this family of resistant insects survives and

proliferates.

Field biologists have often observed that animals reared together from an early age become imprinted on one another and lack mutual sexual interest as adults:

But what they are avoiding, according to William Shields, a biologist at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry at Syracuse, is merely incest, the most extreme form of inbreeding, not inbreeding itself.

He argues that normal patterns of dispersal actually encourage inbreeding.

When young birds leave the nest, for instance, they typically move four or five home ranges away, not 10 or 100; that is, they stay within breeding distance of their cousins.

Intense loyalty to a home territory helps keep a population healthy, according to Shields, because it encourages "optimal inbreeding."

This elusive ideal is the point at which a population gets the benefit of adaptations to local habitat - the co-adapted gene complexes - without the hazardous unmasking of recessive disorders.

A study conducted by E.L. Brannon, an ecologist at the University of Idaho, looked at two separate populations of sockeye salmon, one breeding where a river entered a lake, the other where it exited.

Salmon fry at the inlet evolved to swim downstream to the lake. The ones at the outlet evolved to swim upstream.

When researchers crossed the populations, they ended up with salmon young too confused to know which way to go. In the wild, such a hybrid population might lose half or more of its fry and soon vanish.

For instance, the size and shape of our teeth is a strongly inherited trait.

So is jaw size and shape. But the two traits aren't inherited together. If a woman with small jaws and small teeth marries a man with big jaws and big teeth, their grandchildren may end up with a mouthful of gnashers in a Tinkertoy jaw.

Before dentistry was commonplace, Bateson adds,

Marrying a cousin was one way to avoid a potentially lethal mismatch.

The similarities are social, psychological, and physical, even down to traits like earlobe length. Cousins, Bateson says, perfectly fit this human preference for "slight novelty."

No scientist is advocating intermarriage, but the evidence indicates that we should at least moderate our automatic disdain for it. One unlucky woman, whom Robin Bennett encountered in the course of her research, recalled the reaction when she became pregnant after living with her first cousin for two years.

Her gynecologist professed horror, told her the baby "would be sick all the time," and advised her to have an abortion.

Her boyfriend's mother, who was also her aunt,

The woman had an abortion, which she now calls,

Science is increasingly able to help such people look at their own choices more objectively.

Genetic and metabolic tests can now screen for about 100 recessive disorders. In the past, families in Bradford rarely recognized genetic origins of causes of death or patterns of abnormality.

The likelihood of stigma within the community or racism from without also made people reluctant to discuss such problems.

But new tests have helped change that.

Last year two siblings in Bradford were hoping to intermarry their children despite a family history of thalassemia, a recessive blood disorder that is frequently fatal before the age of 30.

After testing determined which of the children carried the thalassemia gene, the families were able to arrange a pair of carrier-to-noncarrier first-cousin marriages.

It may even be the sort of thing that causes Americans, with their entrenched dread of inbreeding, to shudder.

But the needs of both

culture and medicine were satisfied, and an observer could only

conclude that the urge to marry cousins must be more powerful, and

more deeply rooted, than we yet understand...

|