|

Believe it or not, this article does indeed belong on Classical Wisdom instead of a publication like Modern Magazine!

Here's why… Ever since the world's first known analogue computer - the famous Antikythera mechanism - emerged from an ancient Greek shipwreck in 1901, historians have been trying to come to terms with the fact that,

The mechanism was first believed to be nothing more than a lump of rock.

In 2012, it was revealed to be a complex system of cogs that could perform more calculations than a Swiss watch.

The discovery led to an increased interest in ancient technologies. Researchers have been re-examining old discoveries and making new ones, and the results have been enlightening.

So, without further delay we present five technological discoveries from Greece and Rome that are surprisingly ancient.

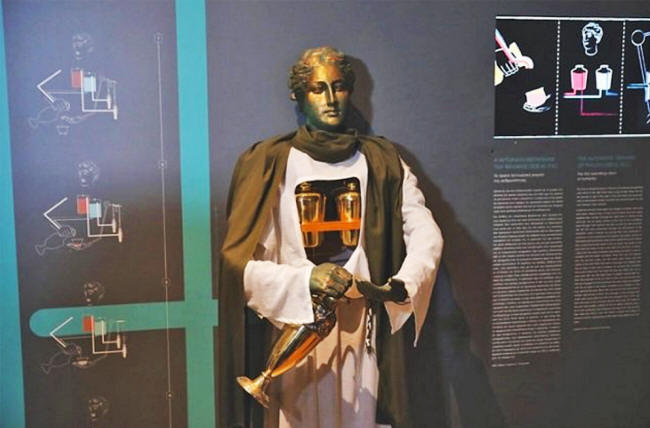

The automatic servant of Philon (3rd Century BC), by Philo of Byzantium

The automatic servant of Philon from the 3rd century BC, is seen at Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology in Athens, Greece February 13, 2020. PHOTO: REUTERS

Invented by Philo of Byzantium in the third century BC, the automatic servant of Philon is currently recognized as the world's first robot. It is a human-shaped automaton that dispenses wine when a cup is placed in its hands.

The Greeks were known for diluting their wine with water, and the automaton is designed to do just that. Once the cup is placed in the empty hand, wine is poured followed by water.

The liquids are dispensed in turn using a series of pipes hidden within the robot that lead from the robot's arm to a central chamber in the torso.

The pipes are controlled by air valves that open when the arm lowers with the weight of the cup, and close again once the cup is removed.

A series of vending machines that dispensed holy water were built by Hero of Alexandria using a similar mechanism. Valves were activated when a coin was dispensed.

These machines were common at the entrance of holy places.

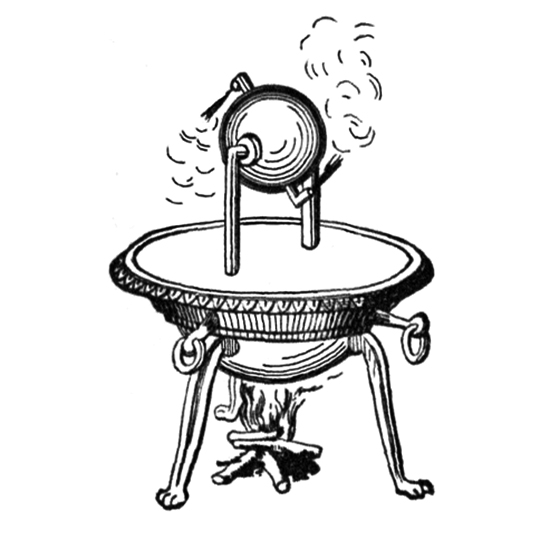

Aeolipile (The First Steam Engine)

An illustration of Hero's aeolipile

Also known as a 'Hero's Engine,' the Aeolipile is the first world's first-known steam engine.

The Aeoliple was believed invented as a demonstration of steam power, and not intended for any practical purpose. Even so, the machine is evidence of the period's revolutionary scientific experimentation.

There is speculation that this invention did have a predecessor, as a similar device was mentioned by Vitruvius in his treatise De Architectura.

However, historians say it could be the same device, which would make the invention slightly older than currently thought.

Astrolabe

A modern Iranian flat Astrolabe (Tabriz, 2013), by Jacopo Koushan

Similar to the Antikythera Device, the Astrolabe was an intricate device used by astronomers and navigators to measure altitude.

The mechanism was designed to be used day and night.

The Astrolabe made specific altitudinal calculations based on the horizons of celestial bodies. It was also used to identify stars and planets, and could provide the local latitude data based on a given local time (and vice versa!).

The earliest Astrolabe was invented by Apollonius of Perga somewhere between 220 and 150 BC.

The design is an amalgamation of two earlier inventions the planisphere (a device used to calculate stars using two rotating disks) and a dioptra (a tubed device used to measure angles).

The Astrolabe is not only a great invention in its own right, it is also evidence of how the ancient scientific community took inspiration from existing discoveries, just like scientists today.

The Lycurgus Cup

The Lycurgus cup

The Lycurgus cup is named after the mythical figure King Lycurgus, who adorns it.

The cup changes from red to green depending on the light source. The discovery of this color-changing cup, dated to fourth-century Rome, baffled scientists for decades.

Recent investigations have discovered that the color-changing effect is produced by a painstakingly intricate process whereby minute shards of silver and gold nanoparticles, about 70nm in diameter, are diffused within the glass, causing the light to scatter and create the illusion that it is changing color.

What is amazing about this discovery is that the theory of light scattering in relation to nanoparticles wasn't believed discovered until 1908, and finally proven in practice in 1980.

Scientists and historians are unsure what method the Romans used to create the metallic particles, but they all agree that the ancient Romans were the true pioneers of 'new' nanotech...!

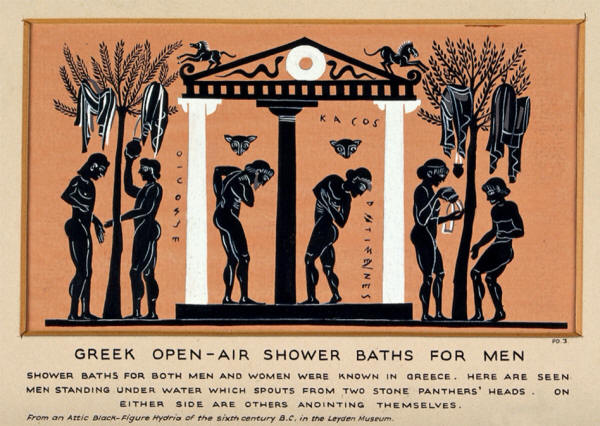

Showers

Greek open-air shower baths for men, gouache painting. Credit: Wellcome Collection

It may not sound exciting, but the invention of showers possibly changed the lives of Ancient Greek people and beyond.

The first shower was rudimentary - literally a hole in the wall, with a servant pouring water through it from the other side. The invention of lead piping soon revolutionized this method.

Archaeologists stumbled upon evidence of Greek showers in a bathhouse while excavating the ancient Greek city of Pergamon.

The site was relatively close to the sea, and a series of underground pipes collected the seawater and dispensed it within the bathhouse for public showering.

This evidence corresponds with evidence of lead plumbing found at gymnasiums and fragments of carved shower heads.

There is also evidence via scripture and pottery illustrations that this same plumbing technique was common to Greek homes, not just public bathhouses.

It is becoming increasingly accepted that Greek city-states may have added pipes to pre-existing aqueduct systems in order to bring water to showers in private homes as well as public buildings.

|