|

by Christopher Joyce

August 20,

2018

from

NPR Website

Ecologist Chelsea Rochman (left)

and

researcher Kennedy Bucci

dig

through washed-up debris along Lake Ontario.

They're

looking for small particles of plastic

that

make their way into oceans, rivers and lakes.

Chris Joyce/NPR

Plastic trash is littering the land and fouling rivers and oceans.

But what we can see is only a small fraction of what's out there.

Since modern plastic was first mass-produced,

8 billion tons have been

manufactured. And when it's thrown away, it doesn't just disappear.

Much of it crumbles into small pieces.

Scientists call the tiny pieces "microplastics"

and define them as objects smaller than 5 millimeters - about the

size of one of the letters on a computer keyboard. Researchers

started to pay serious attention to microplastics in the environment

about 15 years ago.

They're in oceans, rivers

and lakes. They're also in soil...

Recent research in

Germany found that fertilizer made from composted household waste

contains microplastics.

And, even more concerning, microplastics are,

How microplastics get

into animals is something of a mystery, and

Chelsea Rochman is trying to

solve it.

Rochman is an ecologist at the University of Toronto. She studies

how plastic works its way into the food chain, from tiny plankton to

fish larvae to fish, including fish we eat.

She says understanding how plastic gets into fish matters not just

to the fish, but to us.

"We eat fish that eat

plastic," she says.

"Are there things

that transfer to the tissue? Does the plastic itself transfer to

the tissue? Do the chemicals associated with the plastic

transfer to the tissue?"

Bucci uses a microscope

to look

at a fathead minnow larva

that

has ingested plastic particles.

Chris Joyce/NPR

Rochman says she has always loved cleaning up. She remembers how, as

a 6-year-old, she puzzled her parents by volunteering to clean the

house.

In high school in Arizona

she got even more ambitious.

"I used to take my

friends into the desert and clean up a mile of trash every Earth

Day," she says. "I remember finding weird old dolls and strange

old toys that I thought were creepy, but that I would also

keep."

As a graduate student,

she landed a spot on a research vessel to visit the

infamous floating garbage patch in the Pacific

Ocean.

She and the other

scientists on the trip were supposed to count the plastic as it

drifted by.

She remembers the moment they sailed into the patch,

"Everyone runs up to

the bow and says, 'There's trash, there's trash, everyone start

counting the trash.' And so we all start counting the trash."

But something was wrong.

"We're looking and

it's, like, basically a soup of confetti, of tiny little plastic

bits everywhere," she remembers.

"Everyone just stops

counting. [They] sat there, their backs up against the wall and

said, 'OK, this is a real issue, [and it's] not an island of

trash you can pick up."

To Rochman, a third thing

was also clear:

"The tiny stuff, for

me as an ecologist, this is really getting into the

food chain. You could spend a career studying this

stuff."

So she did...

Microplastics found

along

Lake Ontario by Rochman's team

Chris Joyce/NPR

A world of

plastic

A typical day for Rochman might start alongside sparkling Lake

Ontario, where parks line the shore and joggers and picnickers enjoy

the shoreline scenery.

The lake, however, hides

a mostly invisible menace.

To see it, Rochman's student, Kennedy Bucci, brings us to an

inlet that's ankle-deep in washed-up debris. An apartment building

looms overhead.

They squat down, reach

into the muck and quickly find what they're looking for.

"I'm digging and just

finding more and more," Rochman says. "Like whole bottle caps.

This is insane."

"It's so ingrained in the soil," says Bucci.

She comes here regularly

to collect plastic for Rochman's research.

They work quickly,

filling a jar with bits of plastic.

Rochman, who's not

wearing gloves, inadvertently picks up something she wishes she

hadn't.

"Oh!" she laughs,

flinging it aside. "That's why you've got gloves on," she tells

Bucci, and then gets right back to digging.

Since she started

studying microplastics, Rochman has found them in the outflow

from sewage treatment plants...

And they've shown up in

insects, worms, clams, fish and birds.

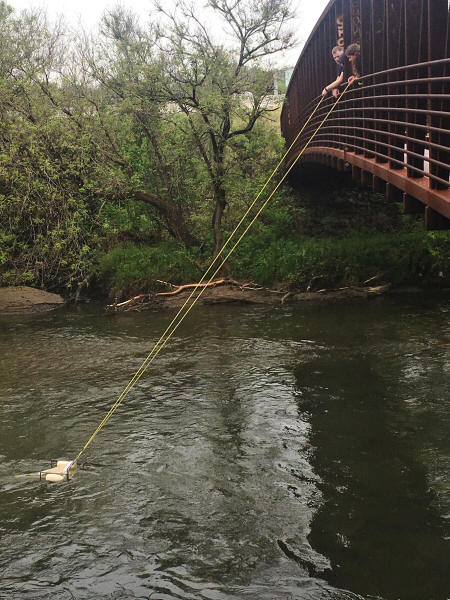

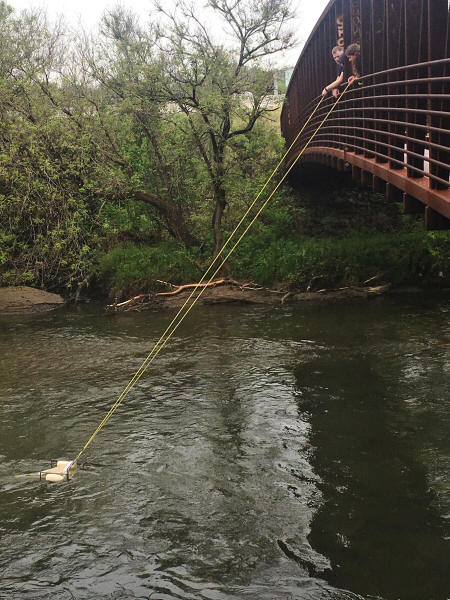

Rochman's scientific team

drops a

net into a stream in Toronto

to

collect tiny floating pieces of plastic.

Chris Joyce/NPR

To study how that happens, Bucci makes her own microplastics from

the morning's collection.

She takes a postage

stamp-size piece of black plastic from the jar, and grinds it into

particles using a coffee grinder.

"So this is the

plastic that I feed to the fish," she says.

The plastic particles go

into beakers of water containing fish larvae from fathead minnows,

the test-animals of choice in marine toxicology.

Tanks full of them line

the walls of the lab. Bucci uses a pipette to draw out a bunch of

larvae that have already been exposed to these ground-up plastic

particles. The larva's gut is translucent.

We can see right into it.

"You can see kind of

a line of black, weirdly shaped black things," she points out.

"Those are the microplastics."

The larva has ingested

them...

Rochman says microplastic particles can sicken or even kill larvae

and fish in their experiments.

Plastic can also get into fish tissue, particularly plastic fibers

from clothing such as fleece. Rochman found fleece fibers in fish

from San Francisco Bay.

She also looked in fish

from Indonesia, a tropical country whose residents are not known for

dressing in fleece. She found plastic

in Indonesian fish guts, but no

fibers, suggesting that fish bodies tell a story about what kind of

plastic resides in local waters.

Rochman took this line of research a step further when she bought a

washing machine for her lab and washed fleece clothing. Lots of

plastic fibers came out in the filter she added to collect the

wastewater.

In fact, she has found

microplastics floating in the air...

"If you put a piece

of double-sided sticky tape on a lab bench for an hour, you come

back and it's got four plastic fibers on it," she says.

Resilient, durable

and potentially dangerous

Most plastic is inert; it does not readily react chemically with

other substances, and that's one reason it has been so successful.

Plastic is resilient,

durable and doesn't easily degrade. It's a vital part of medical

equipment and has revolutionized packaging, especially food storage.

But, over time, plastic can break down and shed the chemicals that

make it useful, such as

phthalates and

bisphenol A.

These substances are

common in the environment and their effects on human health are of

concern to public health scientists and advocates, but few

large-scale, definitive studies have been done.

Plastic also

attracts other chemicals in the

water that latch onto it, including toxic industrial compounds like

polychlorinated biphenyls, or

PCBs.

Plastic becomes a

chemical Trojan horse...

Researcher Kennedy Bucci

collects plastics from the shore

of Lake

Ontario in Toronto.

Chris Joyce/NPR

Tracking all those chemicals is researcher Clara Thaysen's

job.

"Right now we're

starting with the common types of plastic, so polyethylene,

polypropylene [and] polystyrene," she explains.

"But, there's..." she pauses and sighs. "There's tons."

Plastic comes in many

forms, with a wide variety of chemical additives depending on how

the plastic is used.

What happens to plastic

over decades just hasn't been studied deeply.

"This happens all the

time," says Thaysen. "We invent something that seems really

great and... we don't think and we become so dependent on it."

Rochman notes that this

kind of research is relatively new; most of the environmental

studies on microplastics have come out within the past 10 years.

"The things we don't

know," she says, "are daunting."

"What are all the

sources where it's coming from, so that we can think about where

to turn it off? And once it gets in the ocean, where does it go?

Which is

super-important because then we can understand how it impacts

wildlife and humans."

She says she's ready to

spend the rest of her career finding out...

|