|

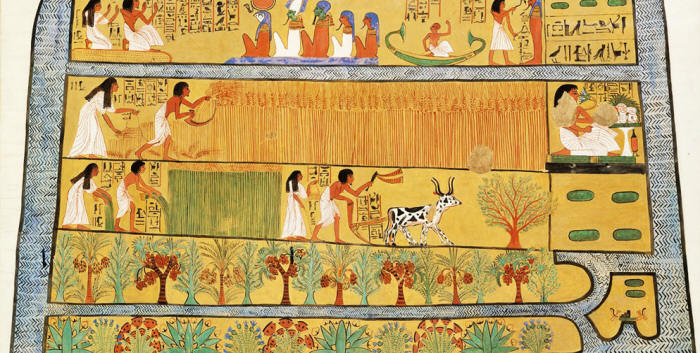

in the Fields of Iar, 1295-1213BC. Charles K. Wilkinson/Met Museum of Art

We recently sequenced (A 3,000-year-old Egyptian Emmer Wheat Genome reveals Dispersal and Domestication History) the genome of a 3,000-year-old sample of Egyptian emmer wheat, and comparisons with modern samples suggest a story of how that crop spread from one region to others.

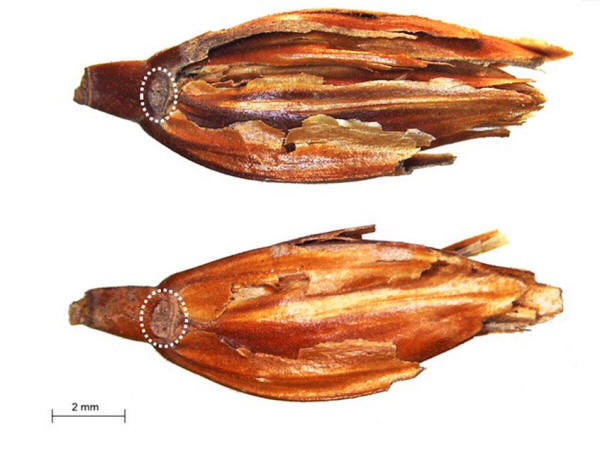

Emmer wheat is "hulled",

which means that strong physical processing is required to separate

the grain from the surrounding chaff. Emmer wheat is a wild hybrid

species that carries two full genomes, each coming from a different

wild grass species.

This means that the hulls are brittle and easily separated from the grain during threshing.

Bread wheat, the most

widely grown crop in the world today, is also free-threshing but

carries one further genome, which comes from a third wild grass

species.

Emmer bread. Michael Scott, UCL Genetics Institute,

Author provided

It is claimed that the Romans therefore referred to hulled wheat as Pharaoh's wheat, which could be the linguistic root of "farro". Egyptians may have found that emmer wheat suited the local climate or that the hulls protected the grain from pests in storage.

Alternatively, the popularity of emmer wheat could be a matter of cultural preference and taste.

We first became aware of ancient cereal specimens in the UCL Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London from a BBC documentary.

The 3,000-year-old emmer wheat chaff that we sequenced was excavated from the Hememiah North Spur site more than 90 years ago by archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thomson and a local workforce.

Despite wartime bombing and flooding - and particularly the sample being stored without climate control - the DNA from the wheat had survived.

Chris Stevens, UCL Institute of Archaeology,

Author

provided

Of cultivated emmer wheats with comparable genetic data available, the Egyptian emmer wheat was most similar to modern emmer grown in,

This suggests a genetic

connection between the early eastward and southward expansions of

emmer cultivation from the fertile crescent, distinct from northward

and westward expansions.

We found that the Egyptian emmer wheat already had most of the genetic characteristics associated with domestication.

Domesticated emmer wheat retains its seeds on the plant, where they can be easily harvested. This would be disadvantageous in the wild because it prevents dispersal. Domesticated emmer wheat seeds are also consistently large and easy to germinate.

These traits were likely

present in the ancient emmer.

However, our study only considers available modern sequences and a single location and time.

In the future, genomic data from more modern and ancient wheats will allow us to pinpoint historical crop movements and changes in genetic diversity. Samples and researchers from relevant regions are likely to play a key role.

It has even been

suggested that the genetic diversity that is present in wild

populations and ancient crops but lost from modern varieties could

be reintroduced to boost crop improvement for the future.

|