|

by Alexandra Witze

January

09, 2019

from

Nature Website

Erratic motion

of north magnetic pole

forces experts

to update model

that aids global

navigation.

Update, 9

January:

The release of the World

Magnetic Model

has been postponed to 30

January

due to the

ongoing US government shutdown.

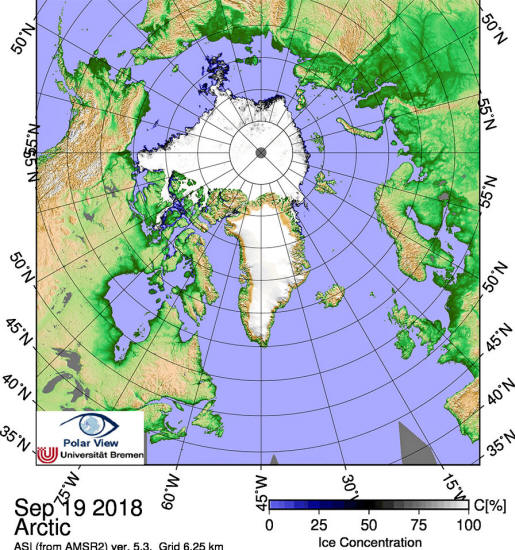

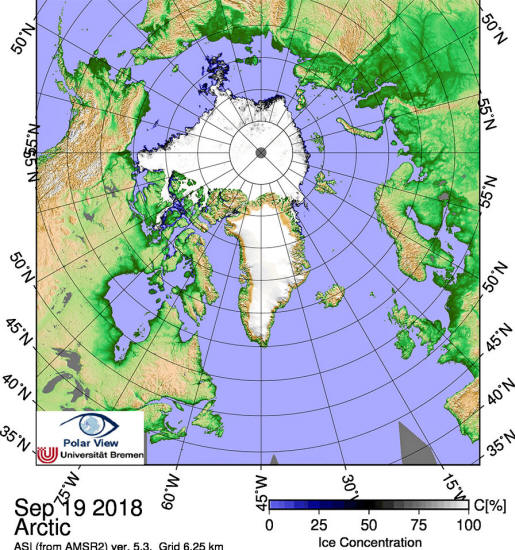

Something strange is going on at the top of the world.

Earth's north magnetic

pole has been skittering away from Canada and towards Siberia,

driven by liquid iron sloshing within the planet's core. The

magnetic pole is moving so quickly that it has forced the world's

geomagnetism experts into a rare move.

On 15 January, they are set to update the World Magnetic Model

(WMM),

which describes

the planet's magnetic field and

underlies all modern navigation, from the systems that steer ships

at sea to Google Maps on smartphones.

The most recent version of the model came out in 2015 and was

supposed to last until 2020 - but the magnetic field is changing so

rapidly that researchers have to fix the model now.

"The error is

increasing all the time," says Arnaud Chulliat, a geomagnetist

at the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA's) National Centers for

Environmental Information.

The problem lies partly

with the moving pole and partly with other shifts deep within the

planet.

Liquid churning in

Earth's core generates most of the magnetic field, which varies over

time as the deep flows change. In 2016, for instance, part of the

magnetic field temporarily accelerated deep under northern South

America and the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Satellites such as the

European Space Agency's

Swarm mission tracked the shift.

By early 2018, the World Magnetic Model was in trouble. Researchers

from NOAA and the British Geological Survey in Edinburgh had been

doing their annual check of how well the model was capturing all the

variations in Earth's magnetic field.

They realized that it was

so inaccurate that it was about to exceed the acceptable limit for

navigational errors.

Wandering pole

"That was an

interesting situation we found ourselves in," says Chulliat.

"What's happening?"

The answer is twofold, he

reported last month at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union

in Washington DC.

- First, that

2016 geomagnetic pulse beneath South America came at the worst

possible time, just after the 2015 update to the World Magnetic

Model.

This meant that the

magnetic field had lurched just after the latest update, in ways

that planners had not anticipated.

Source: World Data Center for Geomagnetism

Kyoto Univ.

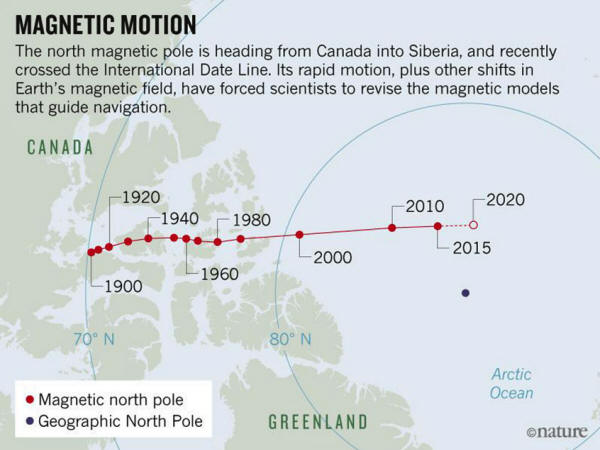

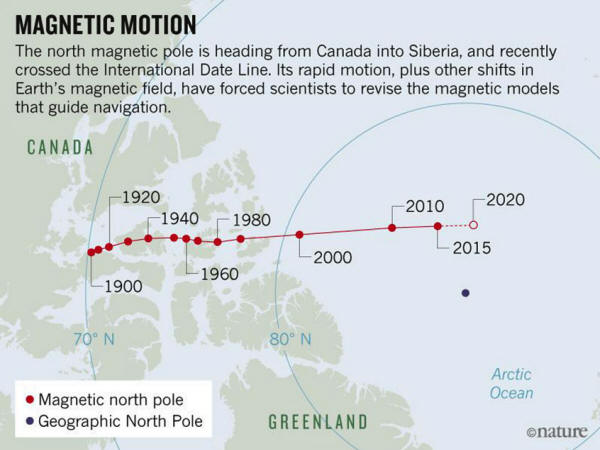

- Second, the motion of the north magnetic pole made the

problem worse.

The pole wanders in

unpredictable ways that have fascinated explorers and scientists

since

James Clark Ross first measured

it in 1831 in the Canadian Arctic.

In the mid-1990s it

picked up speed, from around 15 kilometers per year to around 55

kilometers per year.

By 2001, it had entered

the Arctic Ocean - where, in 2007, a team including Arnaud

Chulliat landed an aeroplane on the sea ice in an attempt to

locate the pole.

In 2018, the pole crossed the

International Date Line into the

Eastern Hemisphere. It is currently making a beeline for Siberia.

The geometry of Earth's magnetic field magnifies the model's errors

in places where the field is changing quickly, such as the North

Pole.

"The fact that the

pole is going fast makes this region more prone to large

errors," says Chulliat.

To fix the World Magnetic

Model, he and his colleagues fed it three years of recent data,

which included the 2016 geomagnetic pulse.

The new version should

remain accurate, he says, until the next regularly scheduled update

in 2020.

Core questions

In the meantime, scientists are working to understand why the

magnetic field is changing so dramatically.

Geomagnetic pulses, like

the one that happened in 2016, might be traced back to 'hydromagnetic'

waves arising from deep in the core. 1 And the fast

motion of the north magnetic pole could be linked to a high-speed

jet of liquid iron beneath Canada. 2

The jet seems to be smearing out and weakening the magnetic field

beneath Canada, Phil Livermore, a geomagnetist at the

University of Leeds, UK, said at the American Geophysical Union

meeting.

And that means that

Canada is essentially losing a magnetic tug-of-war with Siberia.

"The location of the

north magnetic pole appears to be governed by two large-scale

patches of magnetic field, one beneath Canada and one beneath

Siberia," Livermore says.

"The Siberian patch

is winning the competition."

Which means that the

world's geomagnetists will have a lot to keep them busy for the

foreseeable future.

References

-

Geomagnetic acceleration and rapid

hydromagnetic wave dynamics in advanced numerical

simulations of the geodynamo - Aubert, J. Geophys.

J. Int. 214, 531–547 (2018)

-

An accelerating high-latitude jet in

Earth's core - Livermore, P. W., Hollerbach, R. &

Finlay, C. C. Nature Geosci. 10, 62–68 (2017)

|