|

by Tyler Durden

May 07, 2018

from

ZeroHedge Website

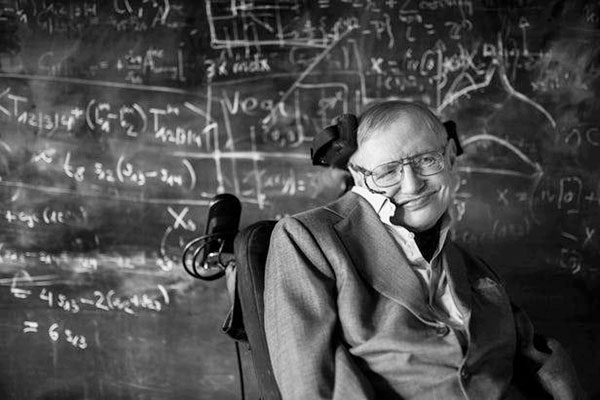

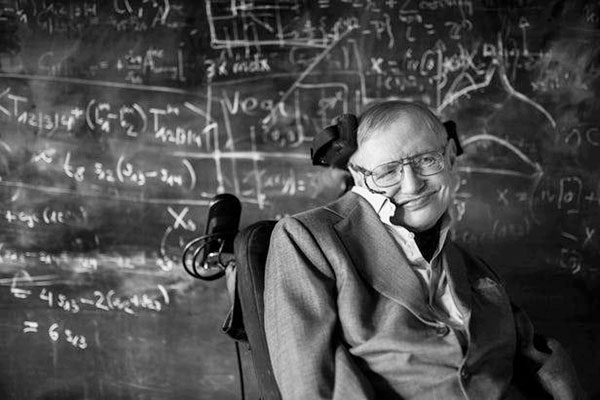

Before he passed

away in March, renowned physicist Stephen Hawking had

published more

than 230 articles on,

But,

ten days before his death, Hawking finished his final theory on the

origin of the universe (A

Smooth Exit from Eternal Inflation?)

- now published posthumously -

and it offers an interesting departure from earlier ideas about the

nature of

the "multiverse."

As PBS

reports, the new

report, co-authored by Belgian physicist Thomas Hertog, counters the

longstanding idea that the universe will expand for eternity.

If you asked an astrophysicist

today to describe what happened after

the Big Bang, he would

likely start with the concept of "cosmic inflation."

Cosmic inflation argues

that right after the Big Bang - we're talking after a teeny

fraction of a second - the universe expanded at breakneck speed

like dough in an oven.

But this exponential expansion

should create, due to quantum mechanics, regions where the

universe continues to grow forever and regions where that growth

stalls.

The result

would be a multiverse, a collection of bubblelike pockets, each

defined by its own laws of physics.

"The local laws

of physics and chemistry can differ from one pocket universe to

another, which together would form a multiverse," Hertog said

in a

statement.

"But I have never been a fan of the multiverse. If the scale of

different universes in the multiverse is large or infinite the

theory can't be tested."

Along with

being difficult to support, the

multiverse theory, which was co-developed

by Hawking in 1983, doesn't jibe with classical physics,

namely the contributions of Einstein's theory of

general relativity as they relate to the structure and dynamics

of the universe.

"As a

consequence, Einstein's theory breaks down in eternal

inflation," Hertog said.

Einstein spent

his life searching for a unified theory, a way to reconcile the

biggest and smallest of things, general relativity and

quantum

mechanics.

He died never

having achieved that goal, but leagues of physicists like Hawking

followed in Einstein's footsteps.

One path led to holograms.

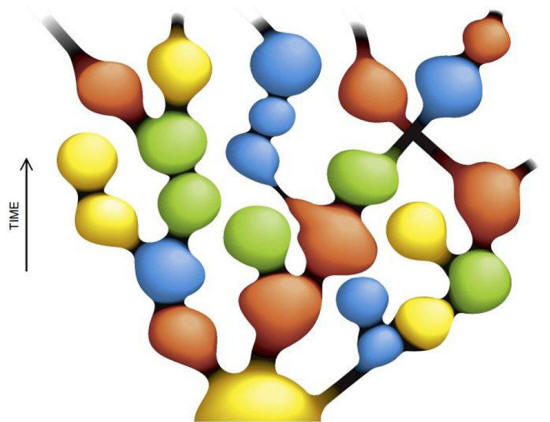

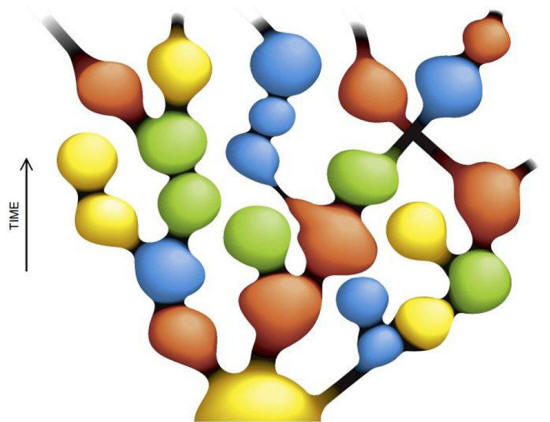

Diagram of

evolution of the (observable part) of the

universe from the Big Bang (left) to the

present.

After the Big

Bang and inflation, the expansion of the

universe gradually slowed down for the next

several billion years, as the matter in the

universe pulled on itself via gravity.

More recently,

the expansion has begun to speed up again as

the repulsive effects of dark energy have

come to dominate the expansion of the

universe.

Image and caption by NASA

Instead of the 'standard' description

of how the 'universe' unfolded (and is unfolding), the authors argue

the Big Bang had a finite boundary, defined by string theory and

holograms.

The new theory

- which sounds simplistically like the world of the

red-pill-blue-pill Matrix movies - embraces the strange concept

that the universe is like a

vast and

complex hologram.

In other words,

3D reality is an illusion, and that the apparently "solid"

world around us - and the dimension of time - is projected from

information stored on a flat 2D surface.

The Telegraph

reports

that Prof Hertog, from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

(KT Leuven), said:

"It's

a very precise mathematical notion of holography that has come

out of string theory in the last few years which is not fully

understood but is mind-boggling and changes the scene

completely."

Applied to

inflation, the newly published theory suggests that

time

and "the beginning" of the universe arose holographically from

an

unknowable state outside the Big Bang...

Prof Hawking said

before his death:

"We are not down to a single,

unique universe, but our findings imply a significant reduction

of the multiverse, to a much smaller range of possible

universes."

And believe it or

not,

there's actually

evidence that the world works this way.

As PBS

concludes,

some physicists point out that the Hawking-Hertog theory is

preliminary and should be considered speculation until

other mathematicians can replicate its equations.

Sabine

Hossenfelder, a theoretical physicist with the Frankfurt

Institute for Advanced Studies, said on

her blog that the ideas put forward in this paper join others

that are currently pure speculation and don't yet have any evidence

to support them.

She makes it clear

that while the proposals aren't uninteresting, Hawking and Hertog

haven't found a new way to detect the existence of universes other

than our own.

"Stephen Hawking was beloved by everyone I know, both inside and

outside the scientific community," she wrote.

"He was a great man without doubt, but this paper is utterly

unremarkable."

Here is

Ars Technica's John Timmer

with more details on the holographic universe.

|