|

by Ethan Siegel from Medium Website

An illustration of multiple, independent Universes, causally disconnected from one another in an ever-expanding cosmic ocean, is one depiction of the Multiverse idea. Image credit: Ozytive / Public Domain.

is all that's out there, prepare to rethink

everything you

knew...

Imagine that the Universe we observe, from end-to-end, is just a drop in the cosmic ocean.

That beyond what we can see, there's more space, more stars, more galaxies, and more everything, for perhaps countless billions of light years farther than we'll ever be able to access.

And that as large as the unobservable Universe is, that there are again innumerably more Universes just like it - some larger and older, some smaller and younger - dotted throughout an even larger spacetime.

As rapidly and inevitably as these Universes expand, the spacetime containing them expands even more quickly, driving them apart from one another, and ensuring that no two Universes will ever meet.

It sounds like a fantasy picture:

But if the science we

accept today is correct, it's not only a valid idea, it's an

unavoidable consequence of our fundamental laws.

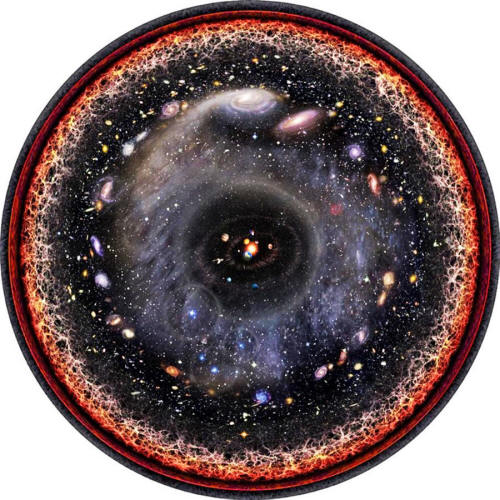

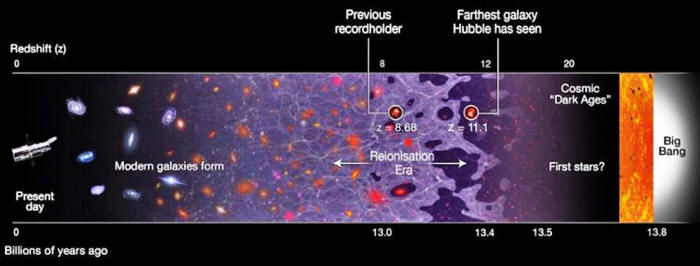

Everywhere we look in the sky, we see stars and galaxies, clustered together in a great cosmic web. But the farther away in space we look, the farther back in time we look as well.

The more distant galaxies are younger, and hence less evolved.

Their stars have fewer heavy elements in them, they appear smaller as fewer mergers have happened, there are more spirals and fewer ellipticals (which take time to form from mergers), and so on.

If we go all the way to the limits of what we can see, we find the very earliest stars in the Universe, and then a region of darkness beyond that, where the only light is the leftover glow from the Big Bang.

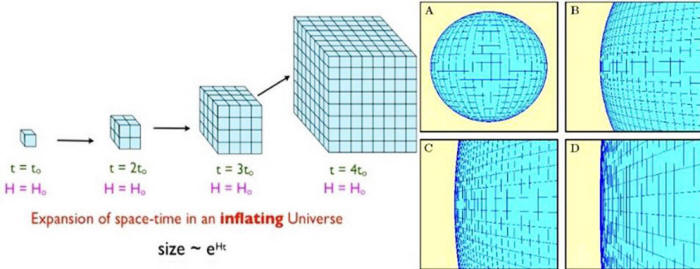

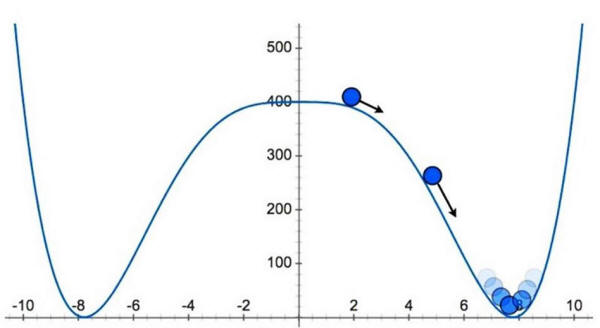

Before that, there was an epoch known as cosmic inflation, where space itself expanded exponentially, full of energy inherent to the fabric of spacetime.

Cosmic inflation is itself an example of a theory that came along and superseded the one that came before it, in that it:

There's also, however, one consequence that inflation predicts that we do not know whether we can confirm or not:

This takes whatever existed before the hot Big Bang and made it much, much, much larger than it was previously.

So far, so good:

When inflation ends, that Universe gets filled with matter and radiation, which is what we see as the hot Big Bang.

But here's where it gets weird.

That transition, and "rolling" down into the valley, is what causes inflation to come to an end, and create the hot Big Bang.

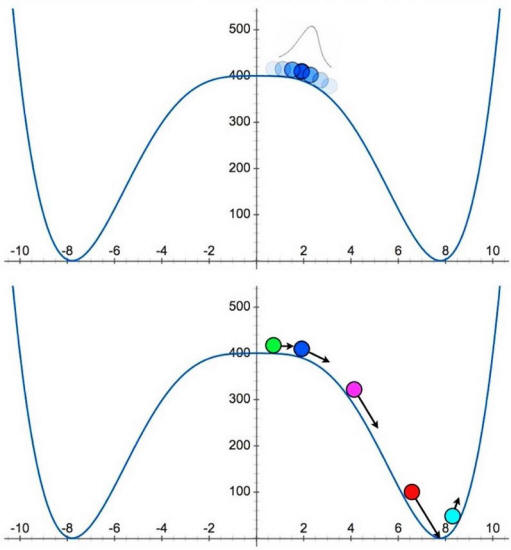

Like all quantum fields, it's described by a wave-function, with the probability of that wave spreading out over time.

If the value of the field is rolling slowly-enough down the hill, then the quantum spreading of the wave-function will be faster than the roll, meaning that it's possible - even probable - for inflation to wind up farther away from ending and giving rise to a Big Bang as time goes on.

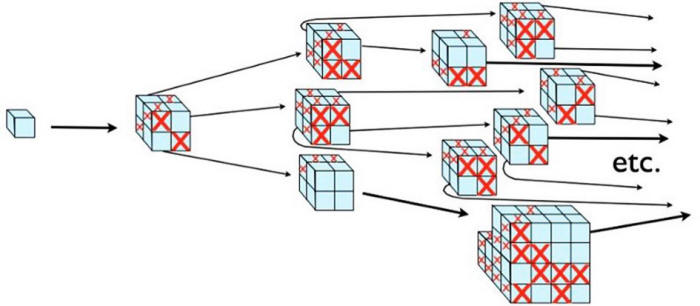

In a few regions, inflation will come to an end:

But in others, inflation will continue on, giving rise to more and more space surrounding each and every region where inflation ends.

The rate of inflation is far more rapid than even the maximum rate of expansion of a matter-and-energy-filled Universe, so in very short order, the inflating parts take over everything.

According to the viable mechanisms that give us enough inflation to produce the Universe we see, there are many more regions of space surrounding our own - where inflation did end - where inflation doesn't end right away.

Where inflation ends, we get a hot Big Bang and a Universe - of which we can observe part of the one we're in - very much like our own. (Denoted by the red "X" above.)

But where inflation doesn't end, that produces more inflating space, which gives rise to some regions that will have hot Big Bangs causally disconnected from our own, and other regions that will continue to inflate.

And so on...

It's important to recognize that the Multiverse is not a scientific theory on its own. It makes no predictions for any observable phenomena that we can access from within our own pocket of existence.

Rather, the Multiverse is a theoretical prediction that comes out of the laws of physics as they're best understood today.

It's perhaps even an inevitable consequence of those laws:

If that's the case, then

the existence of a Multiverse isn't a foregone conclusion, but the

prediction of an eternally inflating state, where an

uncountable large number of pocket Universes are continuously

born and driven inextricably apart from one another, is a direct

consequence of our best current theories, if they're correct.

It may go well beyond physics, and be the first physically motivated "metaphysics" we've ever encountered.

For the first time, we're understanding the limits of what our Universe can teach us. There is information we need, but that we'll never obtain, in order to elevate this into the realm of testable science.

Until then, we can predict, but neither verify nor refute, the fact that our Universe is just one small part of a far grander realm:

|