|

Vol. 13

No 6 (Dec 2019)

Enthusiasts say that

quantum experiments demonstrate that an observer's presence or

perspective determines the nature of objects on a subatomic scale.

But ongoing findings in

quantum physics - when considered without half-baked understanding -

keep pushing the door back open.

Scientific authorities quickly shoot down the starting proposition that quantum theory raises a viable question about the causative influence of the mind, at least in a world of subatomic particles and waves.

Many scientists object

that such notions arise from a misunderstanding of quantum data.

Many people have heard of some version of it.

In essence, more than eighty years of laboratory experiments show that atomic-scale particles appear in a given place only when a measurement is made.

Astonishing as it sounds

- and physicists themselves have debated the data for generations -

quantum theory holds that no measurement means no precise and

localized object on the atomic level.

Critics sometimes argue that certain particles are too small to measure; hence any attempt at measurement inevitably affects what is seen.

Such experiments have repeatedly shown that,

How is this actually provable?

In the parlance of quantum physics,

When particles or waves - typically in the form of a beam of photons or electrons - are directed or aimed at a target system, such as a double-slit, scientists have found that their pattern or path will actually change, or "collapse," depending upon the presence or measurement choices of an observer.

Hence, a wave pattern will shift, or collapse, into a particle pattern.

The situation gets even stranger when dealing with the thought experiment known as "Schrodinger's Cat."

The twentieth-century physicist Erwin Schrodinger was frustrated with the evident absurdity of quantum theory which showed objects simultaneously appearing in more than one place at a time.

Such an outlook, he felt, violated all commonly observed physical laws.

In 1935, Schrodinger

sought to highlight this predicament through a purposely absurdist

thought experiment, which he intended to force quantum physicists to

follow their data to its ultimate degree.

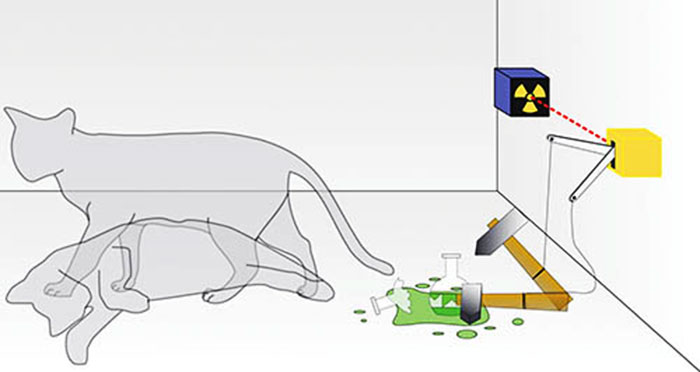

Schrödinger's cat thought experiment: a cat, a flask of poison, and a radioactive source are placed in a sealed box. If an internal monitor (e.g. Geiger counter) detects radioactivity (i.e. a single atom decaying), the flask is shattered, releasing the poison, which kills the cat. The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics implies that after a while, the cat is simultaneously alive and dead. Yet, when one looks in the box, one sees the cat either alive or dead, not both alive and dead. This poses the question of when exactly quantum superposition ends and reality collapses into one possibility or the other.

Of course, all lived experience tells us that if the atom went into the empty box, the cat is alive, and if it went into the box with the cat and the poisoning device, the cat is dead.

But Schrodinger, aiming

to highlight the frustrations of quantum theory, argued that if the

observations of quantum-mechanics experiments are right you would

have to allow for each outcome.

In this line of reasoning, conscious observation effectively manifested the localized atom, the dead cat, the living cat - and also manifested the past, i.e., created a history for both a dead cat and a living one.

Both outcomes are true.

Yes to that, say quantum physicists - but decades of quantum experiments make this model - in which a creature can be dead/alive - into an impossible reality:

Schrodinger's thought experiment forced a consideration of the meaning of quantum mechanics (though not many physicists pay attention to the radical implications).

It may be due to the limits of our observation in the macro world.

Some twenty-first-century quantum physicists call this phenomenon,

The theory of "information leakage" holds that the apparent impossibilities of quantum activity exist all around us. They govern reality...

However, when we step away from whatever instrument we are using to measure micro particles and begin looking at things in larger frames and forms, we see less and less of what is really going on.

William James alluded to a similar dynamic in his 1902 Gifford Lectures:

Only future experiments will determine the broader implications of sub-natural phenomena in the mechanical one in which we live.

For now, however, decades of quantum data make it defensible to conclude that observation done on the subatomic scale:

This last point is sometimes called the "many-worlds interpretation," in the words of physicist Hugh Everett.

This theory of "many worlds" raises the prospect of an infinite number of realities and states of being, each depending upon our choices.

And here we encounter the frustrating but persistent thesis of positive thinking, which holds, in some greater or lesser measure, that our thoughts influence - concretely - our experience.

(1905–1972)

Neville (who went by his first name) argued that everything we see and experience, including one another, is the product of what happens in our own individual dream of reality...

Through a combination of emotional conviction and mental images, Neville believed, each person imagines his own world into being - all people and events are rooted in us, as we are ultimately rooted in God.

When a person awakens to his true self, Neville argued, he will, in fact,

Most quantum physicists wouldn't be caught dead/alive as Schrodinger's cat reading an occult philosopher such as Neville.

Indeed, many physicists reject the notion of interpreting the larger implications of quantum data at all.

The role of physics, critics insist, is to measure things - not, in Einstein's phrase,

Leave that to gurus and philosophers, but, for heaven's sake, critics argue, keep it out of the physics lab.

Others adopt the opposite position:

The latter principle may carry the day.

A rising generation of physicists, educated in the sixties and seventies and open to questions of consciousness, is currently reaching positions of leadership in physics departments (and gaining authority in areas of grant-making and funding).

This cohort was educated in a world populated by Zen and motorcycle maintenance, psychedelic experimentation, and Star Trek:

Hence, we could be on the brink of a renaissance of inquiry into the most remarkable scientific issue since Newton codified classical mechanics.

As more data is known,

purveyors of quantum physics and metaphysics may be headed for a new

and serious conversation.

To the frustration of scientists, spiritual seekers often prove overeager to seize upon the implications of quantum data, declaring that we now have proof that the universe is the result of our minds.

The correlation between the events of the micro world and those of the daily life that we see and feel is far from clear.

Spiritual seekers should resist the temptation to cherry-pick from data that seems to confirm their most deeply cherished ideas.

Such a discussion may,

ultimately, revolutionize how we see ourselves in the twenty-first

century as much as Darwinism did in the Victorian age.

|