|

by Katherine_Kennedy

from ClassicalWisdom Website

March 04, 2020

He bore many different versions of his name whilst growing up; these changed as his familial status was altered first by the death of his father, then his unofficial adoption by his grandfather, and finally his legal coming of age.

Some of the names he was known by include,

But, when Antoninus Pius formally adopted him, as Hadrian's successor, Marcus became heir to the empire, and his name was changed to Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar.

This name would only change once more; when he became emperor.

His final, and full name - Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus - would last until his death.

He was of Italo-Hispanic descent on his father's side and, as such, was a member of the Aurelii, who were based in Roman Spain. The Annia gens is also of Italian descent, with the Annii Veri having risen through the Roman ranks from the 1st century AD.

Marcus was related directly to Marcus Annius Verus (I), his great-grandfather, an ex-praetor, and Marcus Annius Verus (II), his grandfather and unofficial adoptive father, who was a patrician.

She was his grandmother's

half sister, with Sabina and Rupilia being daughters of Trajan's

sororal niece, Salonia Matidia.

from "Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum"

As the daughter of a Roman patrician, P. Calvisius Tullus, her wealth was so great that it included brickworks on the outskirts of Rome - which was a boon in an age of rapid expansion - and Horti Domitia Calvillae/Lucillae, the villa on the Caelian hill of Rome, one of the famous Seven Hills of Rome.

Marcus would later refer to this villa as 'My Caelian', as he was born and raised there, and always remembered it fondly.

But genes and family names do not an Emperor make.

Though Marcus Aurelius was born into noble families, it was his education that would shape the born-leader's mind and harness his abilities.

His adoptive father, Marcus Annius Verus (II), through patria potestas authority when Marcus Annius Verus (III) died around 124, oversaw his grandson's upbringing.

Marcus' education taught him to be of good character and to avoid bad temper, something he recognized as being of great value, and he thanked his grandfather for his wisdom.

Diogenetus, a painting master, also had great impact on Marcus; as it appears it is he who introduced the young man to philosophy and a philosophic way of life.

This extended to Marcus taking up the robes and habits of a philosopher in the year 132.

This involved wearing a

rough Greek cloak whilst studying, and he would sleep on the ground

for a period, although the latter part he would give away after a

time, due to the many frequent and vocal concerns of his mother.

from "Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum"

...all who taught him Latin, with Marcus thanking Alexander for teaching him literary styling, which can be seen in Marcus' Meditations.

From AD 136, Marcus had three Greek tutors,

Late in 136 Marcus' life changed dramatically; he took the toga virilis and began his training in oratory.

After nearly dying, Emperor Hadrian, whilst convalescent in Tivoli, chose Marcus' intended father-in-law, Lucius Ceionius Commodus, as his successor.

Lucius took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar, making Marcus as Lucius' adoptive son, a direct successor to the throne.

In a bold move, and as part of the terms of this agreement between Hadrian and Antoninus, Antoninus was to adopt Marcus and Lucius' son Lucius Verus.

This once again implied that Emperor Hadrian had always kept Marcus in mind for the role of Emperor, eventually.

As the heir apparent to the Empire, he also took the name Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar; a title he would remind himself not to take too seriously with the following admonition:

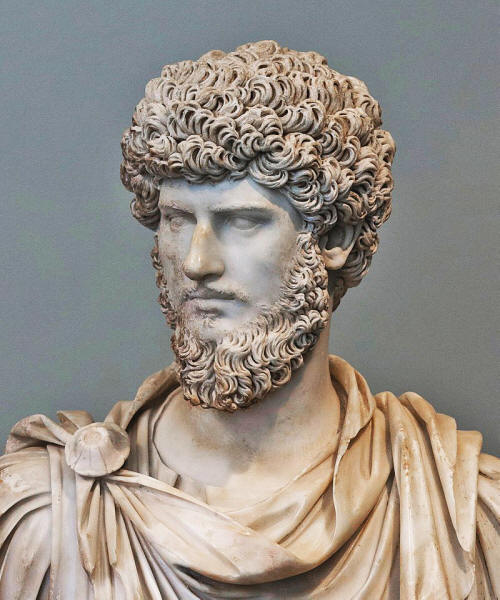

Marble, ca. 161 AD. From the area of Tivoli.

Despite Marcus's objections, he was also required to adopt the habits of his position, the aulicum fastigium or 'pomp of the court'.

As such, he was also made to relocate his home to the House of Tiberius, the imperial palace on the Palatine, something he was loathed to do and which caused him some sadness.

However, through the words,

As quaestor, and under the tutelage of Fronto, Marcus received training for ruling the state. He gained practice by dictating dozens of letters, receiving oratory training giving speeches to the senators, and being educated in matters of State.

In 145 he was made consul for the second time, with Fronto urging him to rest well before his appointment as Marcus had complained of an illness previously.

This ongoing illness would haunt him for many years, especially as he had never been particularly healthy or strong.

At this point, Marcus'

formal education was ended, and his philosophic tendencies began to

return to the fore.

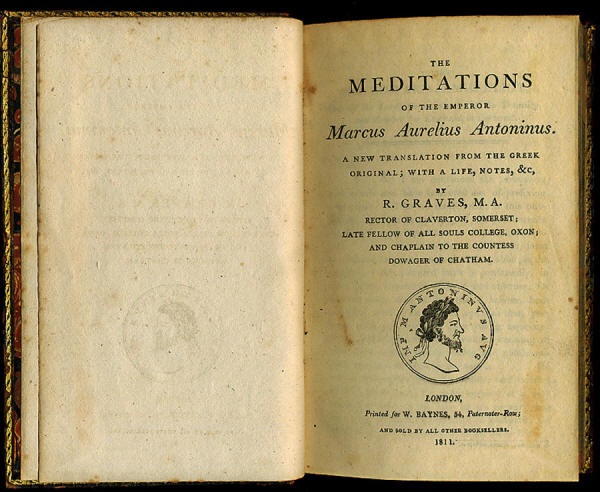

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, translated by R. Graves.

He had contempt for Marcus' sessions with Apollonius of Chalcedon, as it is probably he who introduced Marcus to Stoicism. Fronto's attitude would lead to a distance growing between master and student that would never be bridged.

Marcus would keep in touch with Fronto, but from here on he chose to ignore Fronto's opinions.

During their marriage they would have at least 14 children over a 23-year period; including two sets of twins, and only one son and four daughters outliving their parents.

The first child, Domitia Faustina, was born in 147, and the next day Marcus received tribunician power and the imperium from Emperor Antoninus.

Sadly, this period also marked the deaths of his beloved mother, Domitia Lucilla, and Cornificia, his sister.

This period of emotional upheaval may have contributed to Marcus' downward spiraling health, and cemented his Stoic beliefs:

Antoninus turned 70 in AD 156, and had grown physically weak; needing stays to keep him upright and nibbling dried bread to stay awake through morning receptions.

During this time, Marcus took on more and more administrative duties, including those of praetorian prefect when Gavius Maximus died in 156 or 157.

Marcus and Lucius were both designated as joint consuls for the coming year in 160, as Antoninus was quite ill by this time.

Palazzo Altemps Rome

Having summoned the imperial council, and having handed over the state and his daughter to Marcus, as evening fell and the night-watch came to ask the password, he uttered it before turning over as if to sleep - aequanimitas (equanimity).

So ended the rule of

Anotnius Pius and began that of Marcus Aurelius.

Part II

However, although he was granted the name Augustus and the title imperator, and was elected Pontifex Maximus, Marcus appears to have taken these positions with some hesitation, having to be compelled to do so.

Although Marcus doesn't appear to have had any great sentiment for Hadrian, as he did not mention Hadrian in his Meditations, Marcus was no doubt aware of the former emperor's plans of succession, and ultimately chose to uphold them.

The Senate capitulated,

and two Emperors were now ruling Rome equally, working united, a

first for the Empire.

British Museum.

Marcus held more authority - auctoritas - as he had been consul more times than Lucius, and had been involved in Antoninus' rule and was Pontifex Maximus.

To the public eye, it was clear that Marcus was the senior partner in this joint rulership.

This course of action, winning over the military, wasn't entirely necessary as with previous ascensions, however it was an effective way of solidifying support from the army to the Emperors against any future attacks.

The remains of Antoninus Pius were interred with the remains of Marcus' beloved children, and former emperor Hadrian's remains in Hadrian's mausoleum.

The birth was celebrated

widely, with coins being minted.

During the ceremonies, the Emperors made new provisions to support poor children, something akin to previous imperial foundations.

They also earned favor by permitting free speech, something that had been lacking, with those who spoke out being subject to retribution. Marcus then proceeded to breath new life into the empire, by replacing major officials.

The first to change was the ab epistulis, or those in charge of the imperial correspondence. Next, one of Marcus' former tutors, Lucius Volusius Maecianus was appointed prefect of the treasury, due to his experience as prefectural governor of Egypt.

Finally, Gaius Aufidius Victorinus, Fronto's son-in-law, was made governor of Germania Superior.

Although Fronto did not dare to write to the emperors directly, he did reflect on how the boy he had known had grown into a great leader, and remarked,

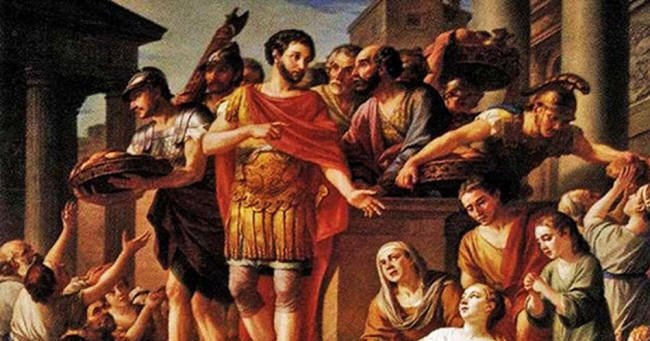

Distributing Bread to the People by Joseph-Marie Vien.

Coinage from the era is stamped with the euphemistic words 'felicitas temporum' or 'happy times'.

Late in 161 or early 162, the Tiber broke its banks and flooded much of Rome. This flooding took the lives of citizens and livestock alike, causing famine and disease to ravage the city.

Marcus and Lucius turned their personal attention to the dire situation, and provided for the communities from the Roman granaries to ease their suffering.

He also noticed that, with this new prominence of position, that Marcus might have ,

...something Fronto was all too keen to assist with, but also reminded him of the differences between Marcus' personal life and his public one.

With Fronto's words,

...he commended his student's rhetorical abilities when the Emperor addressed the Senate after an earthquake in Cyzicus.

It was clear to all who heard his words:

As Emperor Antoninus Pius lay dying, his mind was often consumed by the actions of foreign kings. Such worries would turn out to not be unfounded, though Antoninus would (perhaps fortunately) not live long enough to see his fears justified.

The governor at the time, Marcus Sedatius Severianus, an experienced military man and Gaul, was, unfortunately, mislead by the prophet Alexander of Abonutichus.

Severianus was duped by the snake handler and lulled into a false sense of military superiority.

Vologases IV, minted at Seleucia in 156.

But, the Parthian general Chosrhoes trapped him near the head of the Euphrates River, at Elegia. Severianus attempted several engagements with the general but failed each time.

After three days he committed suicide, leaving his legion to be massacred by the Parthians.

Lucius Verus, Roman Antonine period.

He would spend much of his time in Antioch, wintering at Laodicea, and spending the summers at Daphne, enjoying what were to be his final days as a bachelor.

In the autumn of 163, or early 164, Lucius married Lucilla in Ephesus after Marcus moved up the marriage date; perhaps as a result of Lucius taking a mistress, Panthea.

Some evidence suggests that he was not entirely happy with the arrangement, as he also sent word to his proconsuls not to give the company any official reception.

Eventually, in 165, the Roman forces moved on Mesopotamia, and after a series of skirmishes the Parthian army was routed at the Tigris River, before the Roman army continued on down the Euphrates River for another major victory.

Lucius and the Roman army then turned their sights on the cities of Ctesiphon and Seleucia.

At the end of 165 Ctesiphon was seized, and as the only city that had withstood the Romans, it then faced having the royal palace raised to the ground by fire.

Both of these pillaging conquests would leave a black mark on Lucius' honor and reputation.

Marcus Aurelius (left) and Lucius Verus (right), British Museum.

When the army returned, in 166, to Media, Lucius then added the extra title Medicus to his name, while Marcus chose to wait until then to include Parthicus Maximus to his list of honors.

The two emperors were then hailed as imperatores for the fourth time, and on 12th October Marcus announced his two sons as his heirs-apparent:

Indeed, much of the 160s were consumed with attacks on almost all of the Roman Empire's borders.

There were skirmishes,

Marcus had been ill-prepared for inheriting such a calamitous state, and with very little military experience, he was guided by others.

Unfortunately, Marcus had

replaced capable leaders and governors with friends and relatives of

the imperial family, and this nepotism would come back to haunt him. Where the Roman army had so far succeeded in repulsing the advances of smaller bands of the Germanic tribes, in 168 they faced a much more dangerous combination of united tribes who crossed the Danube.

(series of paintings by Thomas Cole): The Consummation of Empire (1836).

Lucius Verus, having recently defeated the Parthian leader Vologases, was quick to defend the Danubian border.

While fending off this advance, the Germanic tribes began settling in Dacia, Pannonia, Germany, as well as Italy.

While returning to Rome, Lucius became grievously ill with the symptoms of gastroenteritis, although some scholars believe it may have been the Antonine Plague, aka; smallpox.

Just three days later, he was dead.

2nd century relief plates from Ephesus, on display at Humboldt University of Berlin

The co-Emperor would be deified and then worshipped as Divus Verus, soon after the funeral games held in his honor.

Now, as the only ruler, he would spend much of his time in Rome, addressing matters of law. There he would decide over disputes and listen to petitions.

This is something that his predecessors had failed to do:

He also paid particular attention to,

He was a shrewd businessman, seeking the senate's approval before spending money, even though he did not need to do so as Emperor.

During this period, Marcus potentially made contact with Han China, though this tenuous link is via a Roman traveler who claimed to represent the ruler of Daqin.

There is physical evidence to support this story, with Roman glassware being found at Huangzhou, which shares some coastline on the South China Sea, and golden Roman medallions have been found at Óc Eo, in Vietnam, which dates to Marcus' rule, or possibly earlier to Antoninus'.

The Antonine Plague is now suspected to have been smallpox, and was one of the plagues that afflicted the Han Empire at the time of Marcus' potential contact.

with copy of equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius.

The

original is displayed in the Capitoline Museum.

It is believed that during this contact, Roman subjects may have begun a new era of Roman-Far East trading.

However, this exchange of goods may also have instigated the wider spreading of the plague, and caused severe damage to Roman maritime trade in the Indian Ocean.

For instance, archaeological records spanning Egypt to India show decreased traffic, and this had a significant effect on goods going to Southeast Asia at this point.

For much of the 170s, Marcus' rule was spent attempting to stem the onslaught, and in 177 he named Commodus as co-ruler (his other son, Annius, died in 169).

Whatever his intentions, Marcus would not live to see them bear fruit.

He passed away in 180, of natural causes, in Vindobona - modern-day Vienna. He was 58 years old, and his ashes were returned to Rome, and there placed in the mausoleum of Hadrian.

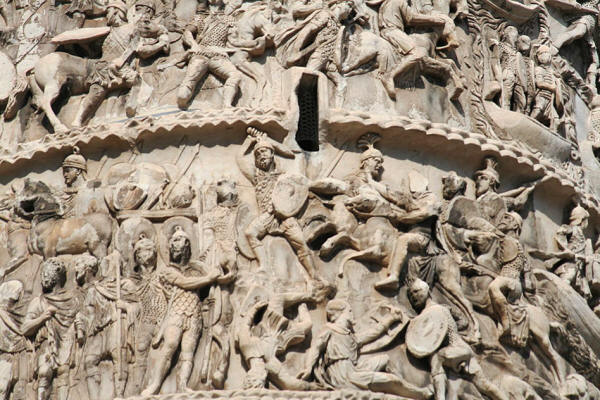

Upon his death, he was immediately deified, and eventually his efforts against the German tribes and the Sarmatians were acknowledged with a column and a temple in Rome.

Column of Marcus Aurelius (in Rome, Italy), depicting a battle of the Marcomannic Wars, late 2nd century AD

Because of his stoic desire to live a quiet life he never sought the limelight of leadership, but when faced with ruling the empire, it was this same stoic attitude of his that allowed him to accept his fate.

It was his natural duty, and he abided by it...

As Cassius Dio wrote, in an encomium to Marcus Aurelius, reflecting on the transition to Commodus and to Dio's own times,

(series of paintings by Thomas Cole): Destruction (1836).

As Dio also said of the man he knew,

Marcus' iconic stoicism, philosophic nature, and compassionate heart meant he constantly worked towards creating a better Roman world.

Marcus lived a life of constant challenges, overcoming them where possible, accepting those that he could not, and all the while striving for the betterment of all.

|