|

from Ancient-Origins Website

Frog brooch of amber and bronze on a rock, representative of living fossils.

Source: ISliM / Adobe Stock

Of course, nothing can survive the conditions of pressure, depth and time required to petrify wood, see saplings mature into massive trees, transmogrify vegetation into coal or metamorphose mud into solid rock.

Still, living creatures seemingly from remotest antiquity keep turning up encased in stone from far beneath Earth's surface, embedded inside solid tree trunks and in other situations defying both reason and the gospel of the 'Great God' Science.

When he wedged loose a

protruding hunk of stone from the tunnel wall it landed on his foot.

Enraged, he grabbed a sledgehammer and smashed it to bits. Molino

was stunned to see his hammer blow had exposed a baseball-sized

cavity in the rock. It was half full of motionless white worms.

Several weeks later the bureau sent the mine operators a letter declaring they must have been mistaken.

Since it clearly is

impossible for creatures to have survived under the circumstances

described, as far as the bureau was concerned there was no way the

incident could have happened.

In 1892 an ore nugget found in an Arizona mine was found to contain a dead beetle from which emerged a live beetle: is that a living fossil or what? (wectorcolor / Adobe Stock)

The ore nugget and its dead inhabitant were turned over to El Paso geologist Z. T. White, who placed the insect in a specimen case.

Several days later he was shocked to see the creature move. Watching through a magnifying glass White saw a small beetle emerge from the body of the larger, dead one.

He placed the small beetle in a jar where it lived for several months.

When it died, he presented it, the larger beetle and the lump of ore to the Smithsonian Institution , where they may remain to this day.

Once in 1893 in Ontario, Canada a live toad emerged from deep inside a tree trunk! (Volodymyr Shevchuk / Adobe Stock)

In 1873, miners at the Black Diamond Coal Mine outside San Francisco found a large frog encased in limestone. This common (but venerable) bullfrog was apparently blind, and able to slowly move just one leg. After several hours on the surface, it died.

The frog and its

entombing stone were given to the San Francisco Academy of Sciences,

where its survival of what would seem an impossible stretch of time

continues to defy understanding.

Living Fossils Story #4: Would you believe it?

The tree was about 200 years old, and the spherical, perfectly smooth hole in which the amphibian was entombed was about 60 feet (18 meters) above the ground.

The toad tumbled from its

wooden prison and hopped away, seemingly none the worse for its long

confinement.

During one of the cuts,

the stone saw revealed a little hole in the middle of a block, and a

toad within it.

Several hours later, after trying one last time to assume its normal crouching position, the toad sank to the pavement and died. Several scientists who later examined the small corpse confessed they were at a loss to explain how the animal could have been found alive under such airless, foodless and waterless conditions.

One of these learned men took the dead animal home with him, and it was never seen again. It was not the first or last impossible fossil yielded by Britain.

As one of the workers was breaking up a large chunk of chalk stone into smaller pieces so they could be removed from the hole he found three newts embedded in the rock.

Clarke placed them in the bright sunlight and was stupefied when they began to move. Two of them died later in the day, and for years he exhibited them to his students during his lectures on prehistory.

He placed the third newt in a nearby brook, and it "skipped and twisted about as though it had never been torpid," and escaped, he later said.

Clarke was never

able to identify the species to which the newts belonged.

During the chaos of the

1940 Nazi bombing blitz these pickled specimens turned up missing.

Unless they were blown to atoms by a Luftwaffe bomb, they may remain

somewhere within Cambridge University, forgotten and still

unexplained.

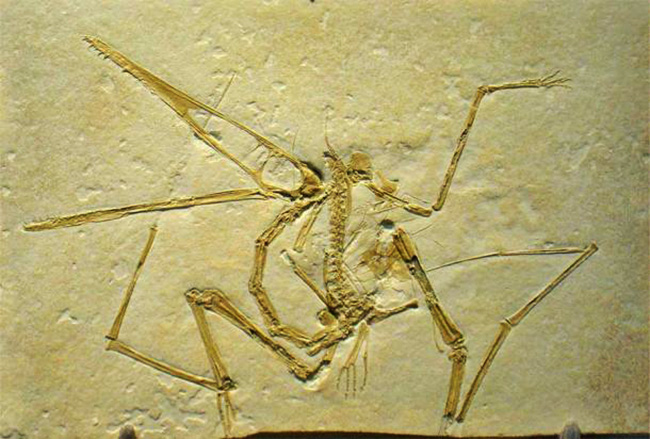

This is a fossil of a flying dinosaur, a Pterodactylus antiquus, and a close cousin of this species was apparently still alive in France in the 1850s according to newspaper reports at the time. (Daderot / Public domain )

The most incredible find of a living fossil is that reported by the Illustrated London Times of February 9, 1856.

The incident occurred in France during the construction of a railway tunnel between the towns of Nancy and St. Dizier. According to the article, workers were breaking up a huge boulder when a goose-sized monster staggered from a freshly exposed cavity and screeched hoarsely before falling dead.

It had a long beak, sharp

teeth, four legs joined by membranes, and feet with long hooked

talons. Its flesh was oily and glossy black.

There is no record of whether the body was preserved and still exists.

Because their metabolisms are conditioned to arouse them upon the advent of the warmth and renewed food supplies of springtime, they are seldom in suspended animation for more than four or five months.

Southern Methodist University professor of biology Dr. John Ubelaker, Ph.D. points out that many organisms possess the ability to lower their metabolisms, and that this function is often triggered by environmental conditions.

This permits survival through difficult times.

are perhaps the most incredible living fossils. A colorized electron micrograph of a soybean cyst nematode and egg. (Agricultural Research Service / Public domain )

The creatures were not

only alive, but so animated they all hopped away.

As he asked his readers,

Ubelaker expands upon this premise:

The erratic and odd sides of the natural world remind us of how much we still have to learn about Mother Earth and the processes that govern her and her multitude of children.

There are doubtless many more living relics of the primordial past awaiting exhumation.

When they do come to light, they should be studied meticulously in order to ascertain how they survived such extremes of time, temperature and deprivation.

The possibility of harmlessly subjecting human beings to suspended animation could solve problems of,

Before we can even start

on such grand aspirations, however, we must admit this potentially

priceless process exists.

|