|

Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, Tufts University December 12, 2011 from NationalHumanitiesCenter Website

and it's all over much too soon. Woody Allen

Given that death is (still) inevitable, which would you prefer for your last months on earth:

Almost everyone I have talked to strongly prefers the sudden-death option, but lightning almost never strikes, and many thinking people have a reasonable distaste for any contrived departure suicide or assisted euthanasia that necessarily involves decision-making by themselves or others.

Why?

Because wherever there are such decisions to be made, about quality of life, or degree of impairment or suffering, there are inevitable opportunities for undesirable motives to creep into the mix:

Any practice that became widespread and socially acceptable would, one fears, carry with it an irresistible pressure towards too much self-consciousness of the wrong sort.

As the philosopher Kurt Baier once quipped, echoing Socrates,

We don't want to end our days wondering if everyone around us is glancing at their watches and sizing up our remaining faculties against some unstated but all too present threshold.

The recognition that one

has "lost a step" on the various playing fields of life is bad

enough without having to consider how it affects the bottom line on

the great spreadsheet of one's life.

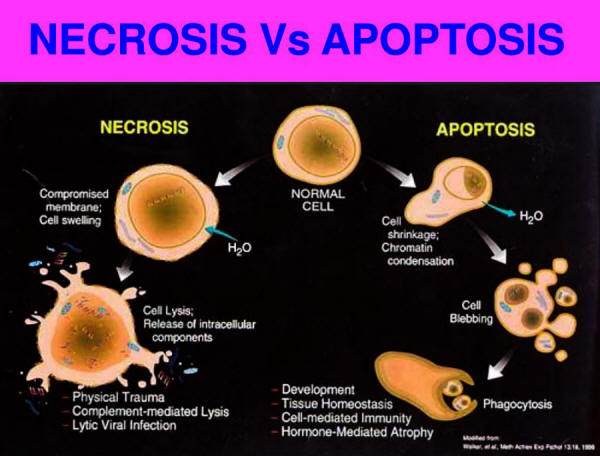

By designing and installing in everyone a robust system of whole-body apoptosis...

As Wikipedia notes:

In contrast to necrosis which is a form of traumatic cell death that results from acute cellular injury, apoptosis is carried out in an orderly process that generally confers advantages during an organism's life cycle.

For example, the differentiation of fingers and toes in a developing human embryo requires cells between the fingers to initiate apoptosis so that the digits can separate.

Between 50 billion and 70 billion cells die each day due to apoptosis in the average human adult. For an average child between the ages of eight and 14, approximately 20 billion to 30 billion cells die a day.

In a year, this amounts to the proliferation and subsequent destruction of a mass of cells equal to an individual's body weight.

Almost nobody would want to know to a near certainty the exact day and hour of their death, and the reasons why are made vivid in any number of death-row dramas.

So a humane system should introduce a substantial element of randomness, elongating the bell-shaped curve of programmed death-knells over a period of, say, five years.

Then you would know to a

moral certainty that if you hadn't already died of some other cause,

then at some unpredictable time between, say, your eighty-fifth and

ninetieth birthday, you would quite suddenly drop in your tracks,

perhaps in the middle of a golf swing, or while trying to finish

writing your latest novel, or even while making love.

We can begin to get some grip on the pros and cons by sketching out the specs for a simple version that may need substantial tweaking:

How could we accomplish this?

The technical details are important, since each conceivable means to this end has some drawbacks or weaknesses associated with it, and we can expect these to be magnified by all manner of human disagreement.

It is quite possibly true - let's think about it - that the ethical and political problems that would beset any such system would make it essentially unimplementable:

In that case, we'll be

stuck with our current dismal ways of dying, but let's

explore the territory to see what might be possible.

The latter is a problem for "evo-devo" (evolutionary-developmental) biologists, who are beginning to understand the cascades of biological clocks that turn on and off various developmental processes.

We know quite a lot about how our biochemistry arranges the timing of such events as puberty and menopause, and we even know that human culture has already "interfered" successfully with such a process in the distant past.

Unlike all other mammals, many of us human adults can digest raw milk, because natural selection has produced a gene that turns off the machinery that would otherwise turn off the production of lactase at weaning.

So common is this genetic revision in our species that we refer to those who lack it as "lactose intolerant" instead of referring to the rest of us as, say, "digestively infantile"!

It was the human practice

of dairying, culturally evolved and transmitted, that provided the

selection pressure for this genetically transmitted adaptation.

I see no reason why we could not now genetically engineer an enzymatic time-bomb that would reliably explode at some time late in life.

Perhaps it would suddenly start spewing endocurarins into the bloodstream, stopping all voluntary muscle movement and hence suffocating the body more effectively than any pillow.

(I am making up the term "endocurarin", inspired by the naming of endorphins, endogenously created opioids that produce such phenomena as the runner's high.

Curare, the legendary blow-pipe dart poison that swiftly paralyzes the muscles leading to asphyxiation, led to the development of muscle relaxants for surgery - D-tubocurarine, for instance - that would kill the patient were it not for the respirator that accompanies its administration.)

(We can already make a

tobacco plant that glows in the dark because it has firefly genes

spliced into its genome.)

I leave further exploration of these and other alternative physiological death-delivery systems to the experts, noting only a few of the obvious desiderata:

(We will explore the

myriad non-genetic side effects of such a system in due course.)

The simplest system, perhaps, would be a time-release poison capsule of the sort now well known to medicine, but with a 20-year (± 1800 days) fuse.

This could be implanted like a pacemaker, and surrounded by tamper-proofing (if you try to remove it surgically, it blows up prematurely).

Better might be the injection of a bio-engineered drug that would begin accumulating something in the bloodstream that would suddenly (after 20 years plus) go haywire.

Needless to say, the reliability and non-toxicity of any such introduction would have to be very, very high before I would volunteer for it, but I imagine it would be only moderately more momentous a life decision than a vasectomy, or undergoing some optional surgery with a low probability of a fatal outcome.

We are becoming used to making such decisions, and for good reason.

(I am going to set aside, for now, the interesting and important economic issues concerning health insurance and life insurance, and the impact such a system would have on them, since I want to stress that this is not a proposal designed primarily to save the taxpayers money or preserve the inheritances of the living, but a proposal designed to reduce the large and inevitably growing amount of pointless suffering that our other technologies have in store for us if we don't change something.)

Given what we know about the controversies surrounding fluoridated water and compulsory vaccination programs, we can expect a firestorm of debate about any such proposals.

But those campaigns also teach us a great deal about how to present such issues and how not to do it.

The "tampering with

God's

will..." objection is getting ever more threadbare and unconvincing

with overuse, and people are beginning to appreciate the benefits of

intervention, and adjust their principles and creeds to accommodate

it.

But technology that they have already come to accept continues to make unprogrammed death ever harder to contemplate and endorse - think of poor Terri Shiavo - so I think the diehards will attract fewer and fewer supporters.

Only a few decades ago, spry 90-year-olds were quite rare, but not today.

That would give quite a few healthy oldsters a few more years of life worth living, but also would fail to kick in soon enough to forestall a lot of suffering.

Clearly, there is no point in adopting such a system unless it actually does cut down most people "in their prime"...!

If you would prefer to die by lightning bolt while you are still effective and healthy, the price you must be willing to pay is foregoing some years or months that would have been just as effective and healthy as your last days.

We haven't had any experience thinking of our lives in terms of diminishing returns, and many will no doubt still feel that more days of life, no matter how painful and confused, is always better than less.

But perhaps we can begin

to contemplate, and take seriously, the idea that just because we

could arrange to live to be 100 (or 120!) we really have no right to

use up so much more than our fair share of the world's resources and

amenities.

One would still have all one's rights, and could go right on working or playing as one chose, perhaps living a bit more riskily, perhaps not.

It should be

remembered that we already know that we're all going to die, and

quite soon, if we're in our eighties. This innovation would

sharpen an existing anticipation, not create something entirely new.

One friend told me that she never appreciated her mother at all until she nursed her through an agonizing death and saw her indomitable will and dignity under horrible conditions.

If this policy had been in force, her mother would have died unappreciated. But that suffering is a huge social cost to pay for such occasional redemptions, I would say.

Besides, the same line of thought could be used to disallow the pain-killers now routinely given in whatever doses are needed to do the trick, on the grounds that we were depriving these poor souls of golden opportunities to prove their fortitude to skeptical family members and other onlookers.

Yes, there would be less employment for end-of-life caregivers who now find their life's meaning in taking care of semi-comatose, incontinent, incommunicative old folks.

Some might be dismayed by the waning of this tradition, but not many, I surmise.

And there would still be

plenty of suffering to witness and relieve, since nothing in this

proposal would guarantee that people wouldn't die terribly prolonged

deaths at age 60 or 70 or 80 of all manner of diseases and

conditions.

Yes, indeed, we could use technology to fine-tune the system, to monitor various plausible measures of quality of life in both individuals and populations,

A mathematical model of expected healthcare savings under variable regimes of apoptosis has already been sketched.

But while these might be possible, and might be desirable improvements, they cut against the spirit of my proposal, which is to use technology to remove this issue from our decision-making options and the incessant monitoring that would rationally follow in its wake.

To give a heightened sense of the flavor of my proposal, consider how you would feel about adopting elaborate falling-in-love-monitoring technology, which could take the guesswork out of romance (and prove its value by a diminished divorce rate, yadda yadda yadda).

We should pause to take seriously - very seriously - the prospect of protecting some aspects of our lives and deaths from management, and thereby reframing our landscape of decisions.

We aren't similarly obsessed with ways of making our descendants taller or stronger or smarter.

Knowing that you could

expect only so many years of life might focus your mind, and will,

wonderfully.

I'd trade any number of

years over 85...

Daniel Dennett "Whole-Body Apoptosis and the Meanings of Lives"

Also HERE...

|