|

by Paul Cudenec

April 19, 2021

from

Network23 Website

"Philosophy which was once the pursuit of

wisdom has become the possession of a technique", as the great

Indian thinker Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan once warned.

1

So it is greatly refreshing, in 2021, to come

across a new philosophical work whose (achieved) aim is not to

perform self-conscious intellectual gymnastics or to catalogue and

categorize the philosophical offerings of previous writers, but to

impart wisdom.

The subtitle of Darren Allen's book "Self

and Unself" is 'The meaning of everything*' and the

asterix points to the addition '(*not literally)'. 2

This is a jokey nod to the kind of humorless literal thinking,

described in the pages to come, which could not allow itself to

appreciate the ironical undertones of the subtitle and would feel

obliged to rebuke Allen for claiming to having provided such an

utterly comprehensive account in a mere 400 pages of print.

Humor, in fact, plays an important part in Self and Unself -

something which again sets it apart from most of the works our

culture would classify as philosophical.

Sometimes it is a question of a laugh-out-loud turn of phrase or

choice of words, such as when Allen warns against allowing oneself

to,

"slump into the pudding of ordinariness that

makes up the mass of mankind", 3

...describes consumer society as,

"a grim Disneyschwitz" 4 or

declares that the vast majority of people are so predictable and

eager to conform because "they come pre-subjugated". 5

Other comic moments are more conceptual, such as

his pondering over the non-existence of,

"postmodern restaurants (selling postcards of

food)", 6 or the thought that an abstract philosopher

is "like a man who empties a box to see what is inside it".

7

On further occasions, the humor comes from a

deliberately-exaggerated bluntness which suddenly punctures the

serious and learned tone of the surrounding prose.

Allen announces with some authority, for instance, that,

"people who can tolerate raw lighting, bad

smells, loud noise, harsh emotions, mental junk-food, pointless

activity and institutional subservience are, despite nursing

whatever hyper-sensitivities they are constitutionally prone to,

generally speaking, morons", 8

...and also judges that the most shallow and

inept category of human being is the "physically attractive". 9

Beneath the humor lies Allen's sadness, which I

very much share, at the degraded condition of modern humans,

"highly specialized infants who can do

nothing but suckle at the tit of the machine". 10

The fairies and

trolls departed, driven out by technology

He describes today's tendency to,

"consider the universe to be entirely

comprised of separate comprehensible parts, particles or

granules relating to each other in predictable ways in order to

produce a measurable outcome". 11

Allen notes that we once lived in,

"a world permeated with magic; until the

fairies and trolls departed, driven out by technology", 12

where "the self still blended seamlessly with the mythic

universe, which centered man and his fellows in nature,

gracefully ordering their progress through it". 13

Not just our lives but also our thinking have

been shorn of all connection to reality, in other words to nature

and thus,

deprived of all depth and

authenticity, reduced to the blind confusion of an auto-isolated

ego...

This is not how it should be, as Allen says:

"Great philosophy, taking the principle of

nature as its source and subject, is like something in nature,

the growth of ivy perhaps, or the song of a wren, or the

activity of an ant's nest; messy perhaps, erratic here and

there, but it holds together as one, and it speaks". 14

'Real philosophy' is in fact the self-expression

of nature, and the universe of which it forms part, via the human

capacity for thought and language.

The idea of nature is never far away from the concept of the

feminine, it being the feminine from which we are all born (natus).

Allen writes:

"The source of creation might be presented as

an egg, or as a lake, or as a serpent, but all these symbols,

and many like them expressive of fecundity, completeness or

generative power, are representations of the common mythological

symbol of unself, the archetypal Great Mother..." 15

He adds that the first sex to "fall" from a state

of natural grace was man, who became gripped by existential fear.

"Women, children, unfallen others, the human

body, and beyond that, the natural universe, including

consciousness itself, became

alien entities which had to be disciplined and controlled".

16

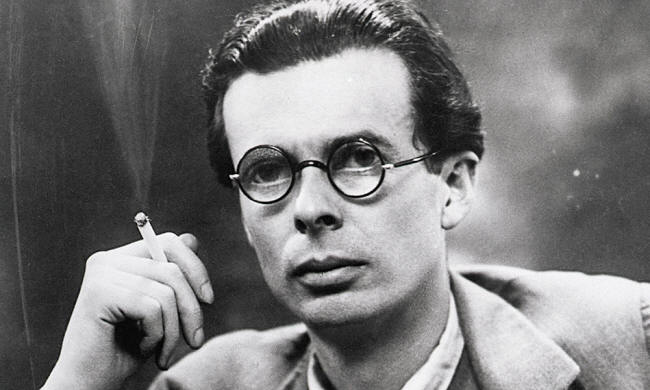

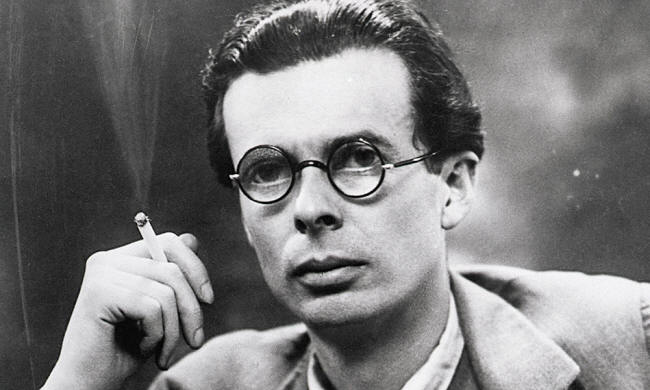

Aldous Huxley

In searching for responses to the debased human condition in modern

society, Allen finds inspiration in the Perennial Philosophy,

as propounded by

Aldous Huxley, Karl Jaspers

and others, although he rightly warns that because of the way

authentic thinking is so often co-opted and corrupted by charlatans,

the perennial philosophy needs to be picked out,

"like blackberries from a forest of thorns".

17

This perennial philosophy presents us with

a truth which has been buried underneath layer upon layer of lie by

all the separated thinking of our culture (including that of

various religions and "spiritual"

schools).

He notes:

"Despite differences in style and emphasis,

there is fundamentally no difference between the message of Lao

Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Jesus of Nazareth (and the great mystics

inspired by him), the message of the Upanishads, the Puranas and

the

Bhagavad Gita". 18

The core of this timeless understanding is the

concept of oneness, the essential truth that is always

denied by the dominant mindset, in every dimension of life and

thought.

The "scientific" fragmentation of reality into separate facts,

causes and effects goes hand in hand with an artificial division of

that all-embracing oneness into separate perspectives of

"subjectivity" and "objectivity".

As I mused myself a few years back, a lot of confusion around

objectivity arises from the way that we cannot actually be truly

objective about a world of which we are part.

But that does not mean that there is no actual,

objective, reality:

"A goldfish in a bowl will never be able to

look at the bowl, and at himself swimming around the bowl, and

gain an objective impression of it.

But the bowl, containing the goldfish, exists

nonetheless". 19

The problem, and this is the basis of Allen's

analysis, is that the modern human has lost touch with the fact that

they belong to a

larger reality, has sawn off the

branch on which they were sitting and falsely imagines themselves to

be something unique and separate.

It is impossible for them to have what Allen terms a "panjective"

view of reality, because they do not understand that when they view

the universe around them, this is really the universe viewing

itself, through the eyes of one of its countless (human) facets.

The

self, or ego, because it is this

separation from the whole, simply cannot recognize or know this

separation, he explains,

"any more than a torch can 'know' darkness".

20

What I particularly admire about this book is the

way in which Allen applies the idea of this separation between self

and unself through every aspect of our being,

thinking and living and explains how the

problem is always essentially the same, whether it manifests

itself in mediocrity and shallowness, in the confusion between

language and reality or in the degradation of art.

What remains

when quality is subtracted from self, is quantity

Particularly important is the link he makes between the

separation of self from unself and the loss of meaning and

quality in our culture - the loss, in fact, of any understanding

that meaning and quality can even exist.

He writes:

"Quality is the 'entry' of unself into self.

The various words we have for quality -

beauty, truth, intelligence, wit, courage, confidence,

innocence, sweetness, sensitivity, goodness, generosity, genius,

love, joy, intensity and so on - express the appearance of

unself-meaning under different circumstances in the self...

What remains when quality is subtracted from

self is quantity". 21

"If quality is ultimately unselfish, then it

is not ultimately something about which self can have direct

knowledge". 22

In the final pages

of the book, Allen goes even

further and presents the self/unself divide in a way which casts new

light on what he has been saying and might encourage the reader to

start again at the beginning with this in mind.

Despite his insistence that he is not offering any "hope", this work

is not only intellectually stimulating but also uplifting.

Allen is convinced that "the entire egoic world must - and will -

fall" 23 and observes:

"Everything at the end of empire is

completely integrated with everything else, which is why it all

had to rise together, and just as it all had to rise together,

so it all must, and will, fall together". 24

Eventually, he says, a point comes when the

illusion and power of ego will shatter.

"Until that grim, chaotic time, the

individual must resist and refuse". 25

In his vision, the conscious human being, who has

released his attachment to the world of artifice, does not fall when

it does.

Instead, he,

"remains standing; on a new earth, watered

with tears of joy, of gratitude.

He is not, after all mad and sick and dead;

it was just winter, and now it is spring". 26

References

-

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,

An Idealist View of Life

(London: Unwin Hyman, 1988), p. 144

-

Darren Allen,

Self and Unself - The Meaning of

Everything (expressive egg books, 2021)

-

Allen, p. 81

-

Allen, p. 252

-

Allen, p. 375

-

Allen, p. 286

-

Allen, p. 42

-

Allen, p. 104

-

Allen, p.167

-

Allen, p. 356

-

Allen, p. 27

-

Allen, p. 313

-

Allen, p. 306

-

Allen, p. 47

-

Allen, p. 296

-

Allen, p. 317

-

Allen, p. 340

-

Allen, p. 338

-

Paul Cudenec, Nature, Essence and Anarchy

(Sussex: Winter Oak, 2016), p. 130

-

Allen, p. 30

-

Allen, p. 55

-

Allen, p. 57

-

Allen, p. 400

-

Allen, p. 399

-

Allen, p. 399

-

Allen, p. 410

|