That Artificial Womb Video isn't Real

-

But Scientists say it

Could Be -

by Rachel Moss

December 13, 2022

from

HuffingtonPost Website

The video looks like

science fiction,

but experts in the field

tell us

it's not such a leap after

all...

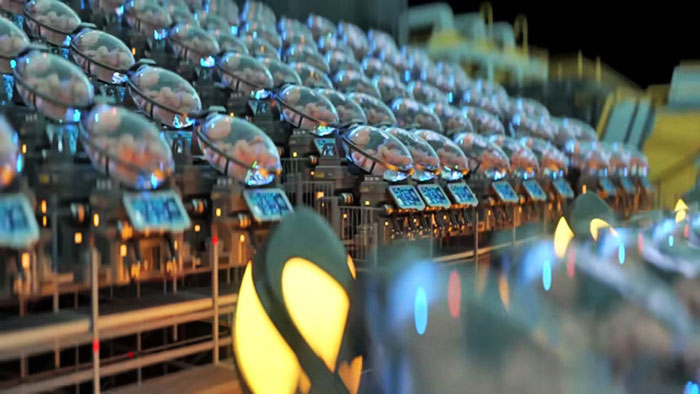

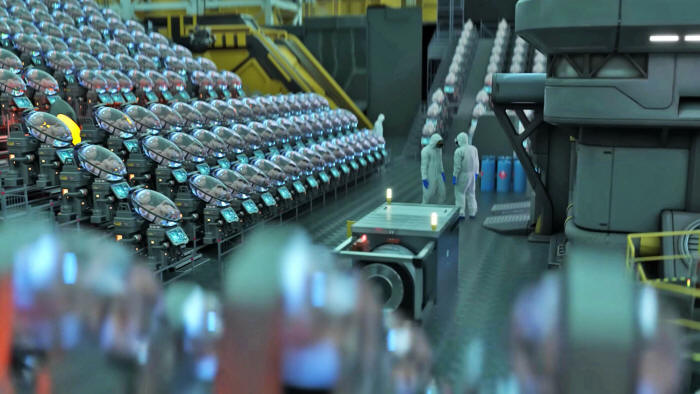

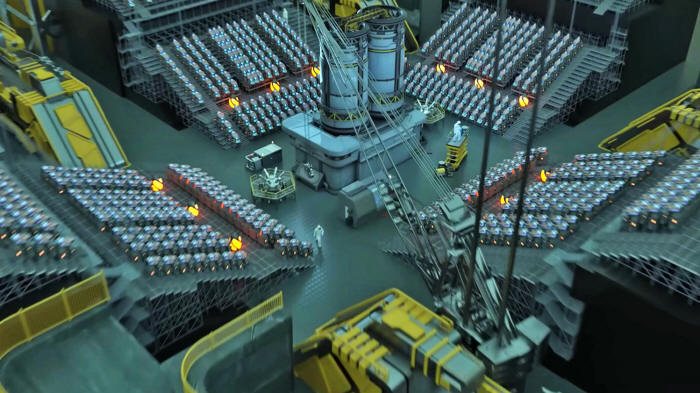

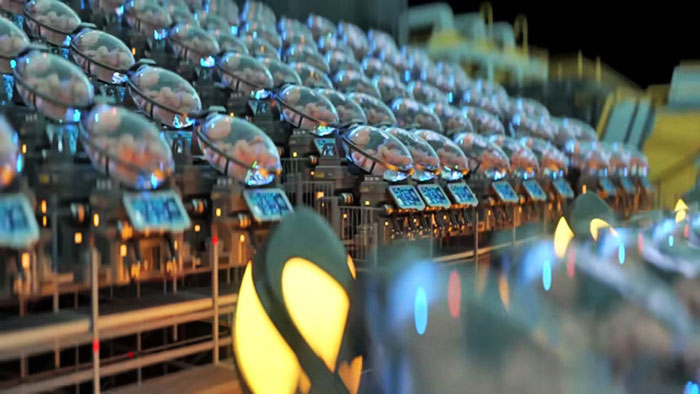

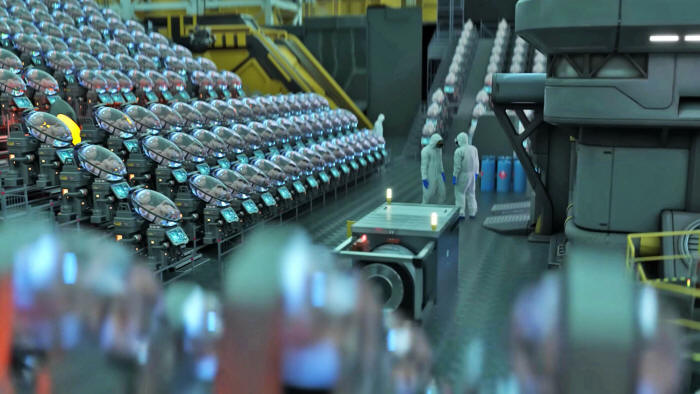

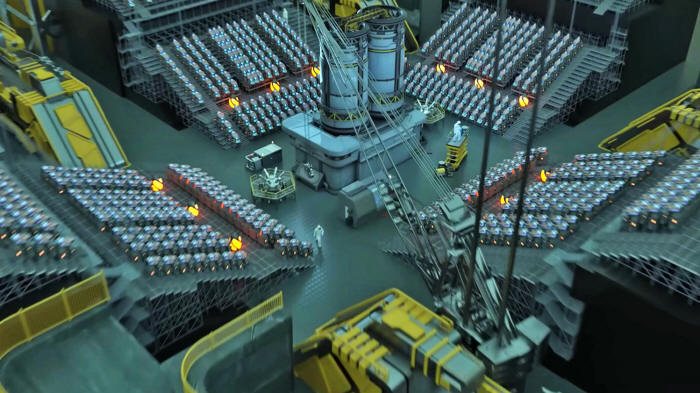

It looks like a scene from

The Matrix.

Rows upon rows of babies are developing in the "world's

first artificial womb facility," which can supposedly

incubate up to 30,000 lab-grown children per year.

But here's the thing - it's not actually "real"...

The futuristic far below video that's being widely shared on social media

is the brainchild of Hashem Al-Ghaili, a producer and

filmmaker with a background in molecular biology.

On

his website, Al-Ghaili says he uses his,

"background in science and technology to develop brand-new

concepts".

He speaks of "imagining the future," though some online have

clearly mistaken his latest film as a real-life advert.

In the video, for a fictional facility called EctoLife,

we hear that,

artificial wombs could provide a solution for

cancer patients who've had their uteruses removed, that they

could reduce pregnancy complications, and that the pods will

help countries experiencing population decline, such as Japan,

Bulgaria, South Korea.

Hashem says he believes this technology is ready and that we

could see such facilities in as little as 10 years.

But what do Scientists Working in this

Field really Think?

Hashem Al-Ghaili

Professor Joyce Harper, head of the Reproductive

Science and Society Group, at UCL Institute for Women's

Health, believes we might.

Her book, 'Your Fertile Years', has a whole chapter dedicated to

what the future of reproduction may look like.

"I have no doubt that at some point, most people will be

produced by

IVF. And that this [EctoLife] would be a

possibility.

In science, I think you should never say never," she tells

HuffPost UK.

"If you just think of the last 50 years and what we've

achieved that you would never have thought of.

I'm quite old, so I remember watching Star Trek, where they

were doing video calls, and you know, I never thought I'd be

video calling my kids on FaceTime."

Hashem Al-Ghaili

She points out that the first four weeks of gestation can

actually be completed in an IVF lab (women are typically four

weeks pregnant when an embryo is transferred).

And now, premature babies can be cared for from around 21 weeks

in an incubator within a neonatal unit.

"A pregnancy is normally 40 weeks and over half of it now

can be done in the neonatal unit," she says.

"So really, it's under 20 weeks [of gestation time], that

scientists have got to figure out how to do safely. It's not

really that far away."

Prof. Harper highlights that

lambs have been been developed from

earlier prematurity, but we're some way off completing this with

humans.

"I do think that this will happen, but not in my lifetime,"

she says.

Andrew Shennan, who is professor of Obstetrics at King's

College London, also says the video isn't as far-fetched as you

may think.

"From a theoretical standpoint it's possible," he says of

artificial wombs.

"It's just a matter of providing a correct environment with

fuel and oxygen and I do think the technologies are there to

be able to achieve that.

"There are lots of examples where babies come out extremely

early and are very well looked after in incubators, which is

a very naive form of what you're talking about, and they're

being fed by tubes down to their stomach.

"When we put people on things like heart bypasses or other

organ bypasses, we are theoretically giving them what they

need from a machine."

Hashem Al-Ghaili

"Though the artificial womb itself wouldn't pose a large

challenge, the early stages of development - where the

organs are forming in the first 12 weeks - would be harder

to navigate," he adds.

Prof. Shennan also says there's,

"all sorts of biochemical and immunological things that go

on that we probably don't understand yet" in relation to

antibodies passed on from the mother.

This would require further research.

There's also ethics to consider, because this technology will

only be developed if there's a need and a desire for it.

The below EctoLife concept video talks about

offering an "elite package" where babies will be genome edited

to alter their hair color, skin tone, physical strength, height

and level of intelligence.

Interestingly, Prof. Harper thinks future generations will be

unfazed by this on an ethical level.

She once took part in an

Oxford Union debate on genome editing and whether it would

"undermine the nature of humanity".

"I spoke for the motion because I think it will, but I can

tell you I lost spectacularly," she says.

"Young people don't have those hesitations that we have."

She thinks the technology will come, but the real question worth

asking is whether we'll want it.

"How many people will find that uncomfortable?

And how many

people will think that's great?" she asks.

Though she personally veers towards the former, she does concede

that this could reduce pregnancy complications and give same-sex

male couples better reproductive choices without the need for a

surrogate, so it's worth considering.

"I have no doubt that in the future, we will have an

artificial human womb, but for now, there are many technical

and social issues we have to overcome," she says.

But Prof. Shennan thinks those ethical battles were largely

covered with the advent of IVF.

"When test tube babies first happened, there was a big

debate and push back, but the test tube baby is now widely

accepted," he says.

"Surrogacy is also a very common phenomenon now. In a way,

you're just asking the machine to be the surrogate, instead

of another woman.

"So I think from an ethical standpoint, I don't think it's

that challenging. Yes, they'd have to be legislation if we

went down that route.

But if you think of the nuts and bolts of the concept, I

think we've already crossed that bridge."

Video