|

by Helena Miton

Photo by Guy le Querrec Magnum

can disappear so easily, why have so many cultural practices survived without written records...?

In fact, most of the cultural practices your distant ancestors learned have not reached you.

They were lost somewhere along the way:

Those chains, it turns out, can be incredibly brittle.

Without physical records, cultural knowledge can easily break down and disappear.

Museums are filled with these enduring messages

about past cultural practices, coded into artifacts and ruins, or

written onto parchment, papyrus and other kinds of media.

Surely, if our ancestors had just given us written instructions on how to speak, farm, cook, dance, and make music, we could have also learned and transmitted that knowledge.

And imagine if they had the recording devices we have today.

With a smartphone, they might have recorded the mundane details of their lives, describing their skills in a way that could be easily mastered and shared.

The problem, however, is that culture doesn't always work that way...

Not everything can be put into words.

Not everything can be understood simply by watching someone else do it.

Some cultural practices can be learned

only by doing. They must be felt...!

It is also why I, a French cognitive scientist in my early 30s, am unable to do many of the things that my ancestors once did, including,

Though our collective forgetting is enormous, it is mostly unremarkable to those who study the transmission of culture.

What puzzles me, and others who study transmission,

Despite the brittleness of cultural practices, skills proliferate with and without records, chaining generation to generation, and binding us to our ancestors in deep time.

Answering these questions will help us understand how much of our current culture could be transmitted to the future.

Though we are living in a time in which cultural knowledge is being recorded and stored at a higher rate than ever before, there is no guarantee this information will be effectively transmitted.

Optimizing cultural transmission, I believe, involves more than new technologies, massive digital repositories and artificial intelligences.

Though culture can be brittle, it is often imagined in ways that make it appear solid and enduring.

When imagined as a kind of sea, culture appears everywhere, surrounding us.

In the 1960s, the media theorist Marshall McLuhan portrayed culture as,

In the 1970s, the anthropologist Edward T. Hall suggested that,

And in the 1990s, the psychologist Michael Tomasello,

Imagined in these disparate ways, culture appears as something solid and enduring that moves forward and expands.

What is a spacecraft, Stanley Kubrick

speculated in

2001 - A Space Odyssey (1968), but the distant

outcome of the first tools used by our hominin ancestors?

Though they can look at rediscovered Mesopotamian bread moulds or ancient Egyptian dancing wands or Chinese oracle bones, they can't bake Mesopotamian bread or dance like ancient Egyptians or consult the Chinese oracle.

These and other findings represent forms of

culture that likely can't be recorded.

stone-knapping remains

a

remarkably difficult skill to learn...

Their work shows just how difficult the task of recreating cultural practices can be.

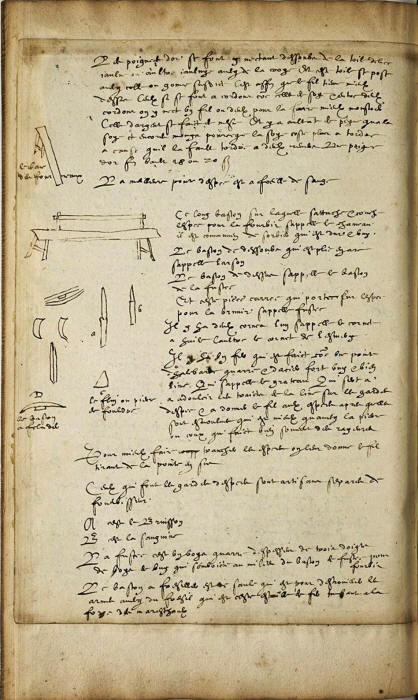

The Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University in New York City has attempted to recreate the techniques described in an anonymous 16th-century French manuscript, catalogued as 'Ms. Fr. 640'.

Between 2014 and 2020, the team tackled techniques described in the manuscript, including,

At the Stone Age Institute, an independent research centre in Indiana, a team is trying to understand stone-knapping techniques used to produce hunting technologies such as arrowheads and spear tips.

Though practiced for millions of years, stone-knapping remains a remarkably difficult skill to learn, requiring extensive training.

The Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University in New York City has attempted to recreate techniques described in an anonymous 16th-century French manuscript, catalogued as 'Ms. Fr. 640'. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Recognizing how difficult it is to transmit cultural practices, UNESCO has been working to preserve 'intangible cultural heritage', which includes many traditions that might become extinct as the last remaining practitioners die.

Languages also fall within this category: around 3,000 remain endangered.

Some, like Aka-Cari spoken in the Andaman Islands, India, have gone extinct only recently.

Cultural transmission is a term used by researchers to describe the process through which certain forms of knowledge are passed between people.

When this knowledge is exchanged, even through passive observation, a 'transmission event' has occurred and another link is made in the chain.

To understand this process in action, think of something you know how to do but would struggle to explain to someone else.

Perhaps it is a specific movement in a sport you play, or a craft technique, or a social skill like knowing the right way to greet another person.

Now, try to think about how long this cultural practice has been around.

Think about how many transmission events might link its first occurrence to the moment when you first learned how to do it.

In some cases, the chain of knowledge might be incredibly long - so long that thinking about the sequence of transmission events might induce vertigo.

This extended sequence can also make the chain appear incredibly delicate. It could have broken at any one of its many transmission events.

This is what makes knowledge chains paradoxical for researchers:

Some solutions to this problem have been elegantly synthesized in How Traditions Live and Die (2015) by Olivier Morin, an expert in cultural evolution.

Morin argues that surviving cultural practices were never that brittle to begin with because they have one or both of the following features:

Both ensure that,

Is it how hard the master blows, or the way they move the molten glass, or something you can't even see?

An alternative way of explaining the paradox between brittle transmission chains and the ubiquity of surviving cultural knowledge involves focusing on how knowledge is stored, not just transmitted.

At first glance, this may appear to make things more challenging for cultural transmission, since this kind of knowledge typically requires learning how a practice feels, which can't be conveyed through words alone.

This is tacit knowledge, or, as the polymath Michael Polanyi describes it, what we know but cannot say.

Language is perfectly suited to convey all kinds of cultural things that are mainly language to start with, such as stories, but many things need to be experienced firsthand.

And what about imitation?

Suppose that you're watching a master glassblower in order to learn how to make a hand-blown cup.

The gap between seeing someone do something skillfully and performing it yourself is often enormous.

To reduce this gap,

In football, for example, a skilful player's moves will depend on the position and velocity of the ball, of their teammates and of their opponents.

You could write 10,000 words about how a goal was scored and still not convey enough information for someone to replicate the kick.

Think about an embodied or tacit form of cultural knowledge you are familiar with, such as,

Now try to break down this practice into bits.

Now, consider how these different bits relate to one another.

As Simon DeDeo and I showed in our article 'The Cultural Transmission of Tacit Knowledge' (2022), a crucial feature of these relationships is constraint: each separate movement or position is limited by our physical bodies and abilities.

Embodied knowledge is strongly constrained.

While riding a horse, for example, if your posture is very straight or you are leaning back slightly, your hands can be only in a limited range of positions; for example, your arms will likely not be long enough to rest high on the horse's neck.

And if your body position changes, and your hands go up, the angle formed by your elbow will shift. Embodied cultural practices always involve physical constraints.

In other words,

Not all bits are necessarily influencing one another in all cases.

Imagine each bit in the network like a switch that can be turned on and off.

When one turns 'on' (say, your hands are high on the horse's neck), others will also turn 'on' (your back will be angled forward) because they are connected.

In other words,

So, if a learner focuses only on mastering those particular traits that matter to a practice, everything else may suddenly click into place more easily.

This echoes something else we observe in real life: experts sharing their embodied knowledge need only home in on those few key bits that are essential.

For a learner, the interactions between the bits, as determined by the network, will then influence the remaining bits, ideally creating a cultural practice that is close to that of their teachers.

Sometimes, changing a tool can shift the network of 'bits', facilitating entirely different movement

For teachers, the skill of sharing knowledge involves knowing which bits to focus on.

In his description of the pedagogical practices used by capoeira teachers, the neuroanthropologist Greg Downey describes their use of,

These teachers can create exercises that, Downey explains,

Such restrictions involve fixing certain bits, at least temporarily, so that other bits will 'click' into place, which allows students to feel what it is like to perform a given movement correctly.

To help reveal the network of bits to new learners, and to generate a transmission event, teachers commonly use metaphors as short-cuts:

None of these metaphors make literal sense:

However, these instructions are still helpful because they allow learners to fix some parts of their movements.

By telling you to 'throw your elbow' when throwing a hook, a boxing coach is helping you align your wrist and your elbow, ensuring your body rotates properly and that you are generating a powerful punch.

Good teaching often requires metaphors or creative exercises that go beyond the practice itself.

Sometimes, teachers may engineer constraints or use metaphors, but artifacts and materials might also exploit the networked relationships between 'bits' to transmit cultural practices.

These artifacts are usually designed to fulfill a specific function or enable a specific use.

More specialized tools and objects act in the same way.

When horse-riding, a dressage saddle, for example, allows for specific positions of the pelvis and legs that are different from those allowed by a jumping saddle:

Materials, like different kinds of wood, earth or stone, also make different actions possible and can help 'fix' some part of the network.

Seeing cultural knowledge as a network of bits that can switch each other on and off means that successful cultural transmission can be achieved even when transmitting only relatively little information.

In such cases,

The unexpected outcome of this is that there can be many ways of doing something, and some learners may even develop unique versions of practices.

In the history of sports, this has happened many times, where examples of unusual or unorthodox techniques abound.

Take Sadaharu Oh's distinctive 'flamingo' leg kick in baseball, or Donald 'the Don' Bradman's batting technique (and exaggerated follow-through) in cricket.

They show that new variants can still be effective, even if they don't become the dominant style.

Sadaharu Oh's 'flamingo' leg kick in baseball

Donald 'the Don' Bradman's batting technique in cricket

However, in some cases, unusual techniques become innovations that alter future transmissions.

One example, again in the domain of sports, is Dick Fosbury's backwards flop in high jump.

After this new technique helped him win gold at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, the Fosbury Flop became popular among high-jumpers, who until then preferred techniques that allowed them to land on their feet.

Dick Fosbury's backwards flop in high jump

Understanding how cultural transmission exploits relationships in a network of 'bits' doesn't only help with the preservation of current knowledge.

It can also give us an insight into new cultural practices that might be discovered in the future.

But putting our faith in this mountain of data may be a 'mistake'...

It is a misunderstanding of the embodied nature of many cultural practices, a misunderstanding of how our ancestors were able to successfully pass practices from generation to generation, despite the inherent brittleness of long cultural chains.

Optimizing the transmission of a cultural practice doesn't always require a larger amount of information.

It is hard to say what forms of culture will exist in another 1,000 or 10,000 years.

But if tacit knowledge is still around,

This is how 'what we know but cannot say' might someday link our age with the cultures of the deep future.

|