|

by Ben Potter

November 01, 2024

from ClassicalWisdom Website

Harmodius and

Aristogeiton

Discover Athenian democracy’s

surprisingly bloody origins,

how it functioned,

and what lessons its use (and

abuse)

have for us today...

Athens, July 514 BC.

Two of Athens' most disgruntled sons,

Harmodius and Aristogeiton become forever known as

'The Tyrannicides'.

With their swords plunged into the Tyrant

Hipparchus, these two soon-to-be martyrs become the symbol

of Athenian democracy.

This is because these brave men's actions paved

the way for Athens to unfetter herself from oppression and tyranny.

Her screaming infancy was at an end:

it was finally time for the demos

(people) to unleash their kratos (power).

So harmony and joy ensued in what was now the

cradle of democracy?

No.

Not at all.

Not even slightly...

Two issues rise starkly out of the noble intentions of our

forefathers; the system... and the results.

But let's deal with the latter first, to see if

any means can justify such ends...!

Athenian democracy, despite a couple of interruptions and

renaissances, is generally agreed to have reigned supreme from

508-322 BC.

Those who know their important dates will see an instant red flag:

Didn't King Alexander the Great die in

323 BC?

How could Athens remain an independent,

democratic state while under the yoke of Macedonian imperialism?

A very intelligent question; you should

congratulate yourself for asking it.

Whilst Athens remained a functioning democracy during the reign of

Alexander the Great, it could not in all earnest be called

independent.

In other words, it was a democratic client

kingdom that could have easily had its powers removed should they

have been used 'irresponsibly' (c.f. American involvement in

Guatemala, Iran, Chile, Brazil, Argentina and even Greece itself).

Despite this technical independence, Athenian democracy did little

to cover itself in glory... even when its self-determinism was

tangible rather than merely theoretical.

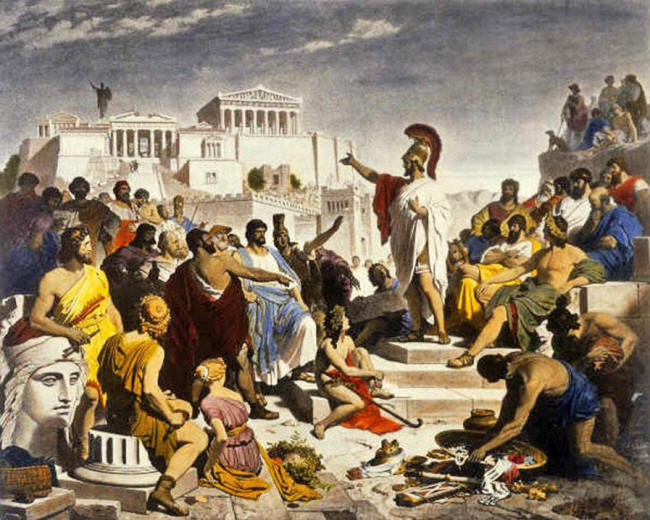

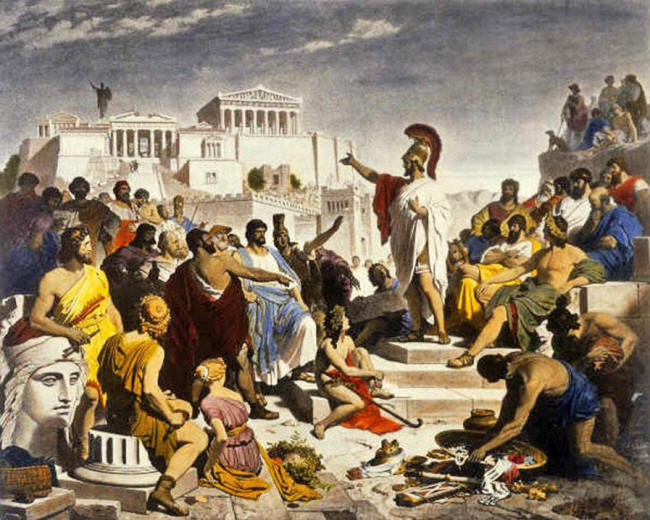

Peloponnesian War

For instance, the bloodthirsty rule of the people forced Athens to

hubristically overstep her reach during the Peloponnesian War

(431-404 BC), which resulted in the temporary suspension of the

democratic experiment.

Importantly, it also seemed suspicious of, and

hostile towards, some of the greatest minds of that time.

Indeed, such was the poor judgment of the demos that it drove the

city's greatest commander (and lover), the legendary Alcibiades,

to flee during the Peloponnesian War and take up residence with

their antagonists, the Spartans.

It has been often speculated, and with much justification, that

Alcibiades' defection was the tipping point in the war.

However, national security was only one sphere in which the people

strove to raise their own standing simply by reducing the mean

quality of the demos as a whole. Art and philosophy were the chief

victims of a short-sighted and covetous populace.

It's thought that popular pressure and threat of persecution forced

the tragedian Euripides to quit the city for a 'retirement'

in Macedonia.

Though some now dispute the veracity of such a

story, the mere fact that it was popularly believed tells a tale in

itself.

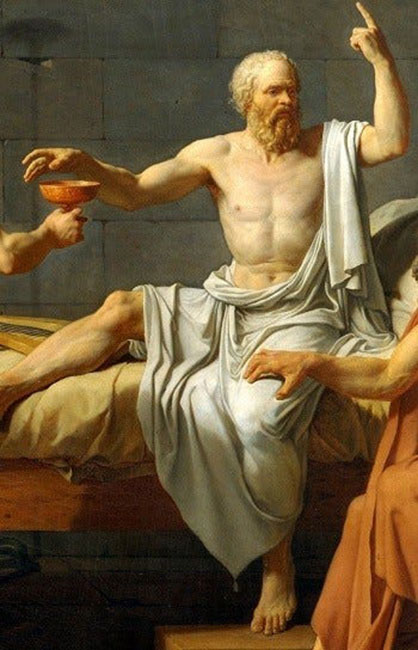

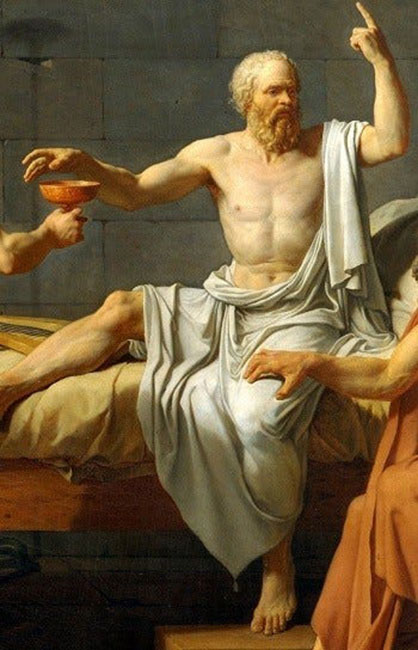

Death of Socrates

Aristotle, likewise, opted to jump before he was pushed into

the next world. He was particularly concerned that the demos would

condemn him to the same fate it bestowed upon Socrates.

Unlike the other three men mentioned above, Socrates was not merely

chased out of town, but actually executed by a jury of 501 of his

peers, greatly multiplying Herbert Spencer's maxim that,

"A jury is composed of twelve men of average

ignorance"...

It is this state-sanctioned murder of one of the

first great minds of our culture that forever leaves Athenian

democracy with an indelible stain.

But can the means do much to exonerate such rancorous ends? Well...

you be the judge.

The Nuts and Bolts

Athenian democracy evolved as any 'work in progress' democracy

should and as such the citizens contributing to the various bodies

of state had sometimes more and sometimes less involvement/power at

different times.

However, the really poignant thing about political participation is

that it was a) assumed and b) direct.

It was taken for granted that men must not merely take an interest

in or talk about politics, but perform actively within the political

arena.

Indeed, men who deliberately spurned politics

were known as idiōtēs.

While the word literally meant 'one who

minded his own business', it was a term of the utmost disdain.

It's from this insult that we get the word

"idiot".

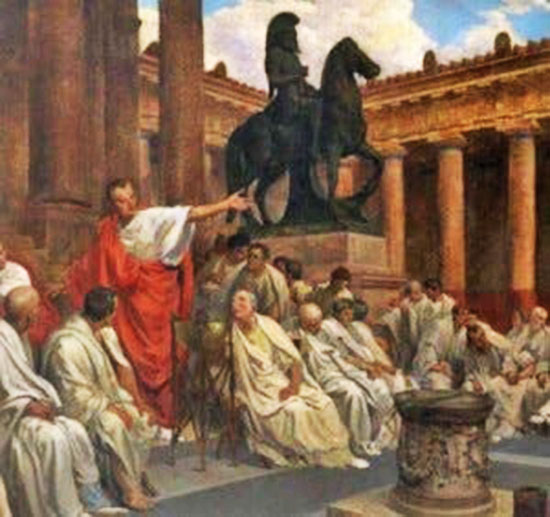

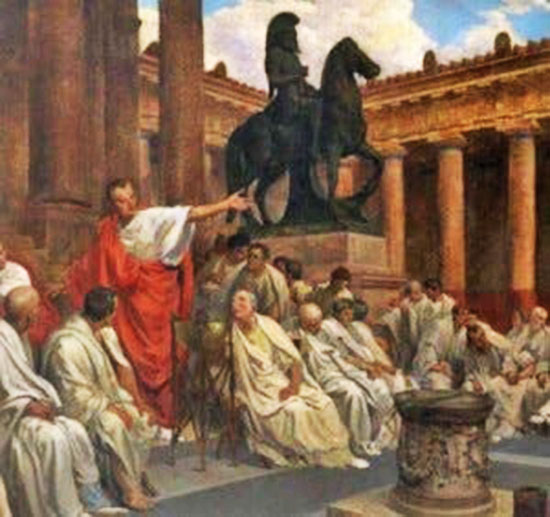

Assembly

The idea that democracy was 'direct' meant that the votes in the

Assembly (ekklêsia) were de facto referenda.

Though minor votes seemed to be able to get

through without much difficulty, major votes could only be passed if

6000 men were in attendance.

Motions carried with a simple majority.

All free men over 18 could vote, but due to the two years of

compulsory military service, political activity usually started at

the age of 20. Women had to wait a bit longer... until 1952 in fact.

However, this imbalance was slightly redressed by

the fact that men had to be 30 in order to hold political office,

sit on a jury or even table a motion!

The Boule

Despite its selectively egalitarian nature, the referendum-style

Assembly was by no means a political free-for-all.

The business of the day was dictated by the

Council (boule). This 500 strong body was the nearest thing that

Athens had to an executive or cabinet.

Even if there was no guarantee that the Council would be selected

judiciously, it was at least selected randomly.

50 members of each of the 10 Athenian tribes

(demes) were appointed by lot to serve for a year with members

from alternating tribes taking turns to lead the Council

day-by-day.

The boule also had to maintain the fleet,

liaise with the generals, entertain dignitaries, assess the

competence of magistrates and handle the city purse.

These last two responsibilities did, for a time

at least, fall in part under the remit of other organs of state.

The Courts

One of which was the courts.

6,000 judges were appointed a year and they

would congregate in the agora to be assigned trials for the day.

Private cases were overseen by either 201 or 401 judges and public

cases by 501.

Trials were supposed to be concluded by sunset,

making jury tampering and corruption not only extremely costly, but

logistically impossible.

The most serious public cases seem to have been political in nature

and were brought against those charged with treason, corruption, or

those who proposed unconstitutional legislation in the Assembly.

N.B.: it didn't matter if the legislation had passed

the vote, the individual could still be tried, condemned and even

executed for misleading the demos.

The demos was always immune from any form

of accountability, if it acted incorrectly it was always because it

had been 'misled'.

The Archai

The day-to-day running of the mundane affairs of state was in the

hands of the 1,200 archai.

1,100 of these former-day civil servants were

chosen by lot with a further 100 being voted for by the Assembly.

Only those voted in could hold the same office

twice (with the exception, by numerical necessity, of those who went

into the boule).

The Strategoi

The only offices not attainable by lot were the 10 associated with

the armed forces.

Consequently, these generals (strategoi) were

the only people who could hope to carve out a political niche

for themselves.

However, such an appointment was fraught with

peril, as the demos was notoriously unforgiving of failure.

The case in point being the 406 BC defeat at the

battle of Arginusae.

Six of the eight generals involved in this

débâcle were tried en masse and executed, despite such a process

being illegal.

The leader in charge of proceedings for the day of the vote was,

amazingly (as it was random which citizen it could have been),

Socrates.

Despite refusing to allow an illegal vote to

take place, the demos went ahead and committed collective

treason against itself.

Some speculate that the enemies Socrates made on

that day may have come back to haunt in him in 399 BC.

The Demokratia

The democrats of Athens believed that demokratia was

intrinsically bound to liberty and equality; they defined the terms

thus:

Liberty = the ability to live as one pleased

and the freedom to participate in politics.

Equality = the right to speak in the Assembly and the right to a

fair trial.

There was not even a suggestion of attempting to

provide men with an equal social or financial status:

democratic Athens was actually extremely

snobbish and elitist.

Free-speech (parrhesia) was thought to underpin

both of these.

Though many critics have pointed out exercising

this was precisely what cost Socrates his life.

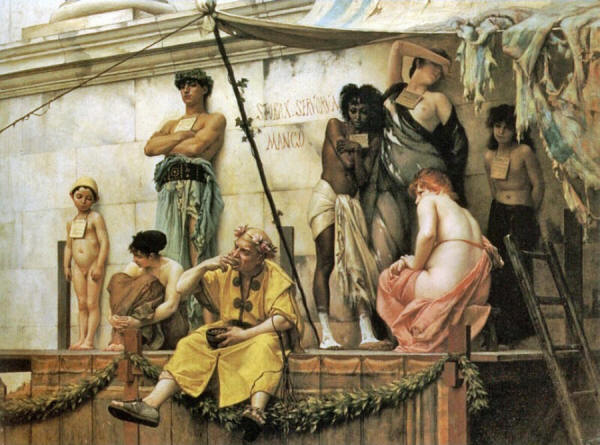

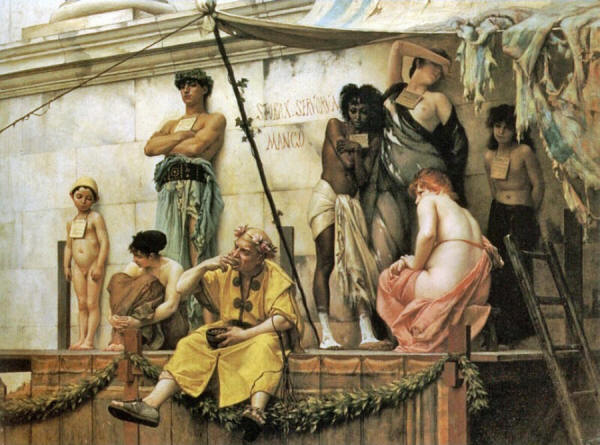

Slavery

Critics have also claimed that, in order to financially sustain such

a democracy, it was necessary for Athens to extend (and then

overextend) her imperial reach.

This included having a slave class

whose ranks were swollen far beyond those of any of her close

neighbors.

Additionally, as the demos could act with impunity, when

mistakes were made - scapegoats needed to be found (e.g. the 6

generals or Socrates).

That said, this was a political system without entrenched parties.

Indeed, it was with few factions of any sort, with minimal

corruption and, most importantly, without any concept of lobbyists!

And we cannot deny that the democratic period gave us some of the

most amazing tragedians, comedians, philosophers, architects,

visionaries, historians and characters the ancient world ever

produced.

Parthenon

Would we have had the Parthenon if not for

Pericles and his building plan?

Or Aeschylus, Sophocles,

Euripides and Aristophanes if theatrical festivals,

competitions and prizes were not organized by the demos...?

Also, perhaps that inevitable product of

democracy, bureaucracy, is why this period of history is one with

such relatively fine records.

The importance of posterity was such that even

the ignominy survives.

Would a king or an oligarchy have been so

transparent?

Ultimately the question must be one of

self-determinism:

were the ancient Athenians content to preside

over the first functioning democracy the world has ever

known...?

Well, the fact that they made Democracy a

goddess in the 4th century BC certainly suggests they

had strong feelings towards its retention.

As does the fact that they relinquished it so

very reluctantly.

One can imagine that, when the Macedonians

wrenched democracy away from the clawing grasp of the demos,

tear-drops, much like the blood from the Tyrannicides' blades

would have salted and stained the terrain at the foot of the

Acropolis...

|