|

by Andrew Perlot

of Socratic State of Mind

January 31, 2025

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

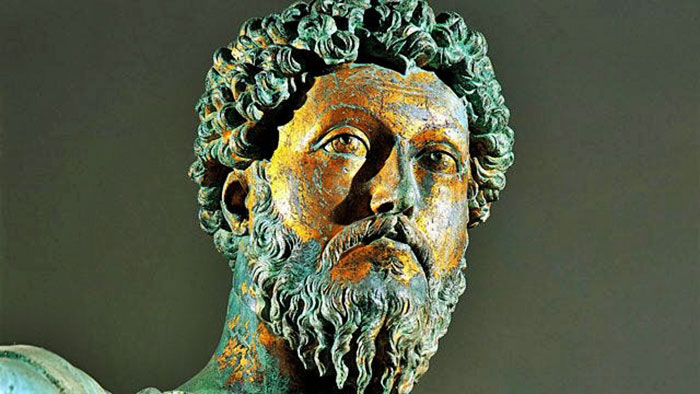

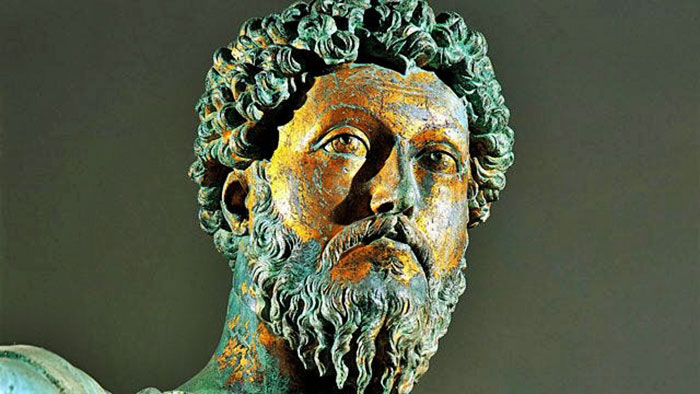

Marcus Aurelius

The paradoxes of Marcus

Aurelius,

the famed Roman emperor and

Stoic philosopher,

are a prime example.

Taken from his much celebrated

Meditations,

they show how the wisdom of the

past

speaks to us anew, across

generations,

centuries, and continents.

Moreover, they're extremely applicable

to our lives today.

Most notebooks don't survive 1,800 years.

Yet the medieval scribes copying the journal of Roman emperor and

Stoic philosopher

Marcus Aurelius - as well the

Renaissance thinkers printing it, and the modern readers who've

periodically returned it to bestseller lists - all thought it

contained something priceless. It changed them.

This isn't accidental.

Marcus's journal,

Meditations, is the foremost

survivor of an ancient philosophical journaling practice in which

record-keeping wasn't the point. Marcus's objective was to change

himself in the moment pen touched paper.

As scholar and philosopher Pierre Hadot noted in The Inner

Citadel...:

"The goal is to reactualize, rekindle, and

ceaselessly reawaken an inner state which is in constant danger

of being numbed or extinguished.

The task - ever-renewed - is to bring back to

order an inner discourse which becomes dispersed and diluted in

the futility of routine."

The Same Old Startling Wisdom

Across the Meditations, Marcus continuously repeats himself

with slightly different wording.

He hunts for the right turn of phrase like

the trained orator he was, trying to craft an incantation to

move an audience of one.

If his ideas lack originality, it was because

he pulled them from a storehouse of well-tested wisdom gleaned

from a lifetime of learning.

He'd gone over these ideas a thousand times

and knew their power to alter him.

He simply redeploys them in new and startling

ways, and they still hit home today for his unintended audience.

You'll find several types of striking phrases in

Meditations - epigrams, maxims, and idea mashups all appear.

But some of his best are paradoxes...

The Other Stoic Paradoxes

Philosophers have long known they can set minds on fire by asserting

seemingly contradictory truths.

This is the art of paradox.

They become earworms that never leave us,

often mentally surfacing when life is most hectic.

Marcus, however, doesn't focus on the six Stoic

paradoxes at the heart of the philosophy.

Perhaps these seemed such a given that they

weren't worth repeating. He focused on what I consider "deployable,"

paradoxes, or ones we might bring to bear in real-world situations.

Here are some of my favorites...

Splendor's Downside

"It is possible to be happy,

even in a palace."

Marcus

Aurelius

Meditations, 4.3

This paradox works on two levels.

First, many balk at the implication that palaces aren't obvious

places for happiness. If you're ensconced in a palace, you probably

have money, power, and influence. People respect you, and perhaps

fear you.

Isn't this - or some modern equivalent - as good

as it gets?

Those with more perspective realize something Marcus - a Roman

emperor who knew a lot about palatial living and power - felt deep

in his bones.

Wealth, influence, and power often lead us

down dark roads.

Sycophants tell the powerful what they

want to hear instead of what's true, a recipe for detachment from

reality and self-centeredness.

This rarely ends well for rich and powerful

people.

It's against this truism that Marcus makes his paradoxical assertion

- actually, you can live well in a palace.

Here Stoicism parts ways with Buddhism.

Where "high level" Buddhist practitioners

flee the palace for an ascetic life of renunciation, Stoics stay

put.

They insist anyone dedicated to philosophy

can be wealthy, powerful, and live in luxury without being

corrupted.

You can live with virtue in a palace, and

therefore you can be happy in a palace.

Philosophical palatial living is harder, but it's

doable. Marcus wrote to remind himself to use his practice to push

back against his worst inclinations and the bad influences at court.

For those of us lower on the socio-economic totem poll, the paradox

is more about correcting goals and desires - collecting wealth,

power, and influence for their own sake won't make us happy in the

long run. It just might ruin our lives.

The further you climb, the further there is to

fall.

So we might as well get off the hedonic treadmill

now.

Passionless Love

"To be free of passion

and yet full of love."

Marcus

Aurelius

Meditations, 1.9

A thousand odes have been written to love, but how many poets

mention the downside?

Anyone who's fallen in love knows there's an element of delusional

obsession to it. You can't stop thinking about the other person;

your mind whirrs and fantasies flit through your mind's eye.

You feel great, but in a slightly unhinged way -

you're not thinking straight.

Stoics insist this isn't love, but pathos, a word they applied to

emotions like anger, fear, unmoored desire, and excessive joy.

Passions are disturbing and misleading forces of

the mind stemming from faulty reasoning and lack of

self-examination, but they're often pleasurable until they lead us

into mistakes.

The Stoics weren't anti-love or anti-feeling - their philosophy

demanded both.

Even Epictetus, the most cantankerous Stoic philosopher of

antiquity whose work survives, admitted that feelings were fine.

"I must not be without feeling like a

statue," he said.

This paradox comes from Marcus's praise of a

beloved teacher famous for his sober, grounded love and kindness

toward all.

This isn't just about romantic love, but about

cultivating love toward all of mankind.

How can we achieve this

passionless love?

As dry as it sounds, forcing yourself to soberly assess and reason

with your delusional passions is the best way to keep yourself from

going off the rails.

You're not going to totally escape the "madness" of falling in love

any more than you'll always be perfectly calm and rational.

Passionate love fades, and we'll doom ourselves to horrible lives if

we have nothing to fill the gap. Someone would need to keep changing

romantic partners and continuously seek out new rollercoasters.

It's critical that we have another sort of

love at the ready - one based on virtue.

Stoics thought expressing that might look like

being loving, trustworthy, kind, etc.

This devotional love doesn't preclude romance and sex, but puts the

wellbeing of your partner first. You commit to treating them justly

and trying to better them.

That goes whether the love is romantic or

platonic.

Obstacle or Whetstone?

"The impediment to

action advances action.

What stands in the way becomes

the way"

Marcus

Aurelius

Meditations,

5.20.

Every misfortune that befalls us and every roadblock we encounter is

an opportunity. We've just been issued an invitation from the

universe to become a better person.

The only real question:

Will we accept it and rise to the occasion,

or reject it and sink into the mire?

Will we wallow or will we grow?

How might we grow?

Most problems have solutions.

Goals might be reached from multiple avenues. So,

a setback is an opportunity to learn new skills or think outside the

box.

But Stoics would say this is beside the point. Even if no solutions

exist, we can still grow by becoming more virtuous, and so become

better equipped to endure - and thrive in - our future life,

whatever happens.

We might use a setback to become wise, just, courageous, and

moderate.

When Kindness Subverts

"Kindness is invincible"

Marcus

Aurelius

Meditations,

11.18

"Kindness is invincible," seems like a nonsensical oxymoron.

How well did kindness work against Viking

raiders slaughtering the unarmed monks of England so they could

steal their golden relics?

In a hardened world, kindness seems an

inexcusable luxury opening us up to abuse by the wicked.

Yet kindness was demanded by the virtue of justice Marcus

continuously references in Meditations, and on at least one occasion

he almost seemed to use it offensively in a manner that protected

him.

When the war hero Avidius Cassius - Marcus's trusted general

- proclaimed himself emperor in 175 A.D., it threatened to tear the

empire apart. The senate responded by declaring him and his

supporters public enemies and confiscating all their property,

stripping them and their heirs of their wealth and land.

But Marcus countermanded the order, saying that anyone who laid down

their arms - including Cassius - would be fully pardoned.

It was a shrewd move...

Cassius' supporters, who may have followed him

into rebellion because they'd been ordered to rather than because

they wanted to see him on the throne - now no longer had their backs

to a wall.

Before it had been win or lose everything,

but Marcus had changed the game.

Now it was a matter of win, or end the senseless war before it

cost tens of thousands of lives.

A cabal of officers killed Cassius and the war

ended on the spot...

Whether you think Marcus was exercising clemency and kindness or

merely making a shrewd power move, you have to admit that it worked.

He protected himself better with an act of

forgiveness than a sword or suit of armor ever could.

Implement Like An Emperor

Of course, it's one thing to admire these paradoxes and another

thing to live them.

Marcus and Epictetus knew all about philosophical dilettantes who

talked a good talk but never lived up to their principles. With all

the power and adoration surrounding him - all those distractions -

It would have been easy for Marcus to fall into that trap.

Meditations is a record of his daily attempts to

stay free and close the gap between his principles and his actions.

If you want to do the same, it's not enough to read. It's not enough

to admire. You also need to close the gap, which means an active

practice and journaling like a philosopher.

You must, as Marcus Aurelius instructed

himself,

"fight to be the person philosophy tried to

make you."

|