|

by Dr. K.R. Bolton

March

18, 2017

from

NewDawnMagazine Website

New Dawn

Special Issue

Vol. 10

No 3

|

DR.

K.R. BOLTON, Th.D.,

is a

Fellow of the World Institute for Scientific

Exploration, and a contributing writer for Foreign

Policy Journal. His 2006 doctoral dissertation was 'From

Knights Templar to New World Order: Occult Influences in

History'.

Widely published in the scholarly and general media, his

books include Revolution from Above; The Parihaka Cult;

Babel Inc.; Perón and Peronism; Stalin - The Enduring

Legacy; The Banking Swindle; The Psychotic Left;

Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific; Zionism, Islam and the

West. |

For those who believe the spiritual realm intersects with the

mundane, there are a multitude of references across time and place

that warn of a spiritual 'combat'.

Saint Paul and John of

Patmos spoke of such things, as did Hopi elders, Jeremiah, the Hindu

holy texts, the Voluspa of the Norse, the Muslim historical

philosopher Ibn Khaldun, and our Western counterparts

Oswald Spengler and Julius Evola, as well as René

Guénon who wrote of the present era as the 'reign of quantity'.

Many thinkers such as

Evola, Guénon and Rudolf Steiner, speaking from first-hand

experiences, identified a conspiracy by 'Black Adepts' to enslave

humanity to matter (the physical realm), detached from the cosmos

and separated from the Divine.

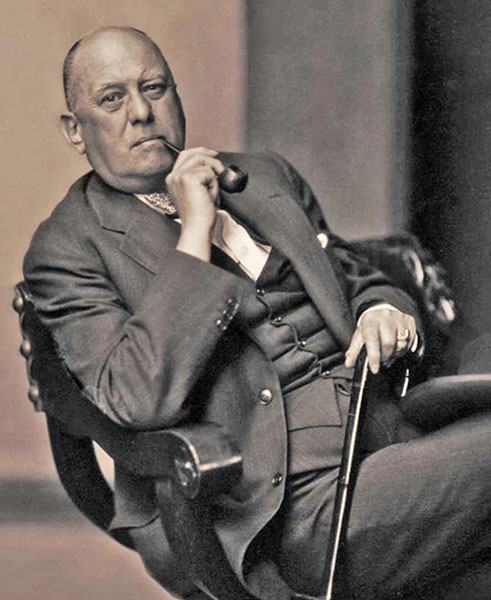

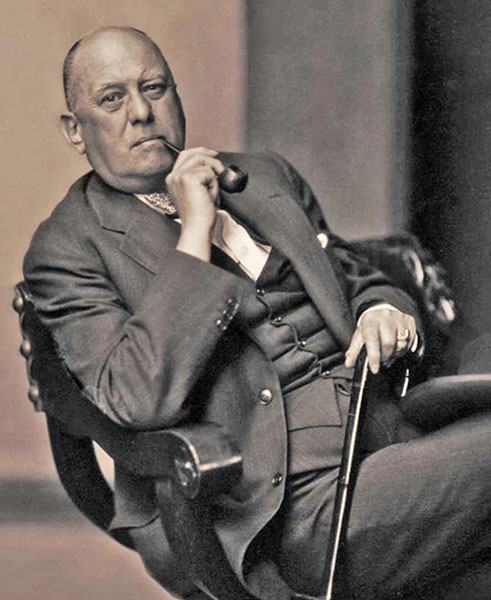

Among those who warned of this increasing dehumanization was the

'infamous' British occultist

Aleister Crowley, scourge of respectable English

society during the 1920s, portrayed by the tabloid press as a

'Satanist' and 'the wickedest man in the world', but also an

operative for the British secret service in both the major 20th

century world wars. 1

Far from being a 'Black

Magician', Crowley sought to oppose the 'Black Adepts' in what he,

along with Steiner, Evola and Guénon, et al, saw as an occult war.

Crowley's doctrine, when

applied to the political, social and economic spheres, is contrary

to that of the Anti-Traditionalist and Counter-Traditionalist

currents addressed by Evola and Guénon.

Thelema is aristocratic

rather than communistic, despite incongruous allusions by Crowley to

Adam Weishaupt and the Illuminati. 2

Thelema is the antithesis

of Illuminism, Jacobinism, secular humanism and other such currents

that emerged from Freemasonry.

Crowley explained that while the Yellow School "stands aloof,"

"the Black School and

the White are always more or less in active conflict." 3

He wrote of the nexus

between the Black School and

Freemasonry, and how Masonry

had been taken over and redirected by the Black Masters and their

adepts.

According to Crowley:

The meaning of

masonry has either been completely forgotten or has never

existed, except insofar as any particular rite might be a cloak

for political or even worse intrigue. 4

Crowley also referred to

English Masons,

"in official

relationship with certain masonic bodies whole sole raison

d'etre is anti-clericalism, political intrigue and trade

benefit," despite English Masonry supposedly eschewing such

motives. 5

Thelema and Nietzsche

To the mass movements and doctrines that were sprouting in the name

of 'the people' but can only result in tyranny, Crowley offered what

he intended to be the religion of a new Aeon, Thelema, the

Greek word for Will.

"There is no law but

do what thou wilt" 6 is the dictum of Thelema,

misunderstood precisely for what it is not:

anarchism and

ego-driven individualism of the type promoted by the 'Black

Adepts' in the name of democracy, liberalism, human rights

and other popular clichés designed to fracture and

deconstruct society as a dialectical process for

reconstructing a 'new world order'.

Crowley unequivocally

stated that "do what thou wilt" "must not be regarded as

individualism run wild." 7

The essence of Thelema is

the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Crowley lists Nietzsche

as one of the 'saints' of

Thelema in the Gnostic Catholic

Mass. 8 It is Nietzsche dressed up with mysticism and

religious garb.

But Nietzsche also

presented his doctrines in quasi-religious and mystical ways,

calling his most well-known book after the name of the founder of

Zoroastrianism, Zarathustra, and writing Thus Spoke Zarathustra in

the style of an Old Testament prophet.

The dictum of Nietzsche's

Zarathustra is Will. The means of achieving one's will is through

"self-overcoming" 9 that requires the sternest discipline

upon oneself. Nietzsche wrote in opposition to Darwinian evolution,

10 stating that human evolution would be willed, not the

result of random genetic mutations.

This next step of human

evolution would result - if able to 'cross the abyss' of

self-destruction - in the Over-Man. In this - misconceptions to the

contrary - one is most brutal towards oneself, not others.

True Self

Schooled in the occult by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn,

where Egyptian mythology was in vogue, Crowley coated Thelema with a

largely Egyptian façade.

His 'bible', 'The Book of The Law',

Liber Legis, an automatic writing scripted in Cairo by Crowley in

1904, is said to be a transmission from "the Gods" through an entity

named Aiwass, or Aiwaz, depending on the numerological significance,

which Crowley on other occasions referred to as his own 'Holy

Guardian Angel', or 'Higher Self'.

In Thelema this is the 'True Self'.

The only purpose in life

is to discover one's True Self and follow that path regardless of

the hardships; equivalent to Nietzsche's self-overcoming, the

individual's battle against his or her own weaknesses and all

obstacles that stand in the way of following one's path.

This requires, states

Crowley, the harshest self-discipline, and is far removed from

hedonism and self-indulgence. It is what the Muslims call the

'greater Jihad', the fight within oneself. It does not justify any

sociopathic disregard for others.

Thelema's other primary dictum is,

"Every man and every

woman is a star." 11

Since every star has its

own orbit, the course of one's star should not, if the law of

Thelema is correctly applied, conflict with another's orbit or the

path of a True Self.

Again Crowley was clear:

"The highest are

those who have mastered and transcended accidental environment…

There is a good deal of the Nietzschean standpoint in this

verse." 12

Thelema, in recognizing

that everyone has a True Self, does not recognize that the

brightness of all stars is equal. Hence, Thelema eschews socialist

and other neo-Jacobin - and New Age - ideologies that demand

universal equality.

Again, Crowley is clear

when describing Thelema as a stellar religion,

"reflecting the

highly organized structure of the universe," which includes

"stars that are of greater magnitude and brilliance than the

rest." 13

Equality is rejected:

"The is no creature

on earth the same. All the members, let them be different in

their qualities, and let there be no creature equal with

another." 14

Thelema was intended for

the creation of a new aristocracy, one neither blood nor money

based, but the merit of one's own struggle.

Crowley advocated the

Nietzschean revival of a "master morality and a slave morality,"

15 meaning that the great mass of people would always

have servile characteristics, hence, "the slaves shall serve":

16

their characteristics

are to follow those who are innately aristocratic and capable of

fulfilling their True Will to the fullest extent.

The masses are,

"that canting,

whining, servile breed of whipped dogs which refuses to admit

its deity"; "the natural enemy of good government." 17

The new aristocracy would

be able to pursue long-range goals without the encumbrances of

pandering to democratic whims. 18

This aversion to mass

politics shuns the democratic vote,

"the principle of

popular election [being] a fatal folly," resulting in the

election of "mediocrity": "the safe man, the sound man, and

therefore never the genius, the man of progress and

illumination." 19

Thelemic State

That is not to say any Thelemic state would be a crushing tyranny as

per socialism.

To the contrary, Crowley

eschewed all leveling doctrines.

He shared the views of

other creative types of the time, including his arch rival in the

Golden Dawn, W.B. Yeats, and the Italian philosopher

Julius Evola, that all arising mass movements including

Bolshevism, Fascism, and the emerging consumer society with its

cultural leveling, were very much negative developments.

Thelema was also intended as a fighting creed or more aptly, a

knightly creed, to wage a Thelemic holy war against creeds that aim

to suppress freedom.

The 'new Aeon' is, after

all, one of 'force and fire', presided over by the hawk-headed god

Horus.

Crowley saw an era of

conflict preceding the new Aeon, in which the new "aristocrats"

would be in conflict with the masses:

"and when the trouble

begins, we aristocrats of freedom, from castle to the cottage,

the tower or the tenement, shall have the slave mob against us."

20

Again one sees the focus

for the new aristocracy on character rather than either wealth or

birth; a new aristocracy that, like Nietzsche's Over-Man, emerges

through struggle.

Crowley described a government following a Thelemic course as one in

which, far from a hedonistic free-for-all,

"set[s] limits to

individual freedom.

For each man in this

state which I propose is fulfilling his own True Will by his

eager Acquiescence in the Order necessary to the Welfare of all,

and therefore of himself also." 21

Crowley advocated the

organic state, or what was in his time known as corporatism, of

which Fascism was an effort.

The doctrine of the

organic or corporate state (as in corpus, or body) was a broad

movement across the world, often influenced by Catholic social

doctrine as a vestige of Tradition, contending with both capitalism

and Bolshevism.

In the organic state, as

the term implies, society is regarded as analogous to a living

organism:

the government is the

brain coordinating each organ (classes, professions), while the

body is composed of cells (individuals).

This organic conception

of society parallels Traditional societies, as explained by Evola,

22 in which the socio-economic structure was a pyramidal

hierarchy with the guilds at its foundation.

Again, Crowley was

specific, describing the organic state very cogently:

In the body every

cell is subordinated to the general physiological Control, and

we who will that Control do not ask whether each individual Unit

of that Structure be consciously happy. But we do care that each

shall fulfill its Function, with Contentment, respecting his own

task as necessary and holy, not envious of another's.

For only mayst thou

build up a Free State, whose directing will shall be to the

Welfare of all. 23

In fulfilling one's True

Will the individual (cell) contributes to the social organism.

This is a Traditional

view of society where every individual's calling is a reflection of

his character as part of the cosmos.

Anything subverting this

order, such as class struggle - "not envious of another's" task as

Crowley put it - could be described as a cancer in the social

organism, disrupting the correct function of the cells and organs of

society.

The socio-economic structure of a Thelemic state would return to the

guilds as in Medieval society, in which work is not economic

drudgery but one's divine calling. There was no class struggle in

the Medieval world, whether of a capitalist or Marxist nature.

Economic competition was alien to the Medieval mind.

In the European Medieval

period, guilds were the fundamental organs of society.

Crowley alluded to the

guilds when describing the structure of his magickal order, Ordo

Templi Orientis (OTO):

Before the face of

the Areopagus 24 stands an independent Parliament of

Guilds.

Within the Order,

irrespective of Grade, the members of each craft, trade,

science, or profession form themselves into a Guild, making

their own laws, and prosecute their own good, in all matters

pertaining to their labour and means of livelihood.

Each Guild chooses

the man most eminent in it to represent it before the Areopagus

of the eighth Degree, and all disputes between the various

guilds are argued before that Body, which will decide according

to the grand principles of the Order. 25

Crowley's OTO is here

seen as a society in microcosm.

Crowley's ideas on the

organic state, and the role of the arts, are most closely reflected

in the very brief time of the Free State of Fiume, created by

Italian war hero and eminent man of letters, Gabrielle D'Annunzio.

The Free State of Fiume

attracted idealists from all over Italy - Anarchists, Fascists,

Futurists and Traditionalists - into a remarkable experiment,

26 albeit one that seems to have been oddly unmentioned by

Crowley, despite existing when he was present in Italy (1920).

Economics of Leisure

& Art

Crowley said that once obligations to the social order are met,

there should be,

"a surplus of leisure

and energy" that can be spent "in pursuit of individual

satisfaction." 27

Again, we hark back to

the pre-industrial epoch of Europe, when the artisan and peasant in

a village-based economy, worked according to his social obligations,

but had an abundance of leisure that today seems utopian.

Such a renewed social order would include a realistic approach to

money as a means of exchange rather than as the commodity it became

over the course of centuries.

As mentioned in New Dawn,

28 Crowley addressed the issue:

What is money? A

means of exchange devised to facilitate the transactions of

business. Oil in the engine.

Very good then: if

instead of letting to flow as smoothly and freely as possible,

you baulk its very nature, you prevent it from doing its True

Will.

So every

"restriction" on the exchange of wealth is a direct violation of

the Law of Thelema. 29

It seems likely that

Crowley was introduced to new economic theories through A.R.

Orage, editor of The New Age, from whence T.S. Eliot,

Ezra Pound and the New Zealand poet Rex Fairburn also

learned about economics. 30

In a Thelemic state, one might envisage usurers being dragged

through the streets and pilloried in stocks, if not worse, and then

declared a literal outlaw.

Once the material needs of the people are met there would be leisure

to pursue higher callings in life. It suggests the

'self-realization' and 'hierarchy of human needs' model of the

humanistic psychology of Maslow et al, if one seeks a current

theory.

Again, this returns to a bygone era where the peasantry and

townsfolk had an abundance of holy-days.

The work week was five

and a half days.

People also rested on

the day of the patron saint of their guild and of their parish,

and there was, of course, a complete holiday on Sundays and on

holy days of obligation.

These were very

numerous in the Middle Ages - 30 to 33 a year, according to the

province. 31

The work day was based on

sun-rise and sun-set, which meant fewer working hours during winter,

and a few hours longer in summer.

Popular theatre was

lively, and actors were widely drawn from the village folk. Not only

religious themes but burlesque, satire, romance and history were

themes.

Crowley proposes a state in which people are free to pursue higher

cultural attainments.

These things being

first secured, thou mayst afterward lead them to the Heavens of

Poesy and Tale, of Music, Painting and Sculpture, and into the

love of the mind itself, with its insatiable Joy of all

Knowledge. 32

Realising that 'stars'

are of unequal brilliance, Crowley condemned,

"the cant of

democracy," stating it was "useless to pretend that men are

equal," and that most are content to "stay dull." 33

Given every opportunity,

most would be content satisfying their material needs, with no

horizons beyond "ease and animal happiness."

Those whose True Wills

are to ascend the social hierarchy would form "a class of morally

and intellectually superior men and women." 34

Crowley addressed the problems of the machine age, relevant to the

present technocratic era, where man is becoming an economic cog.

What Crowley said about industrialization is prescient in light of

the modern technological age, with its ongoing dehumanization and

life increasingly virtual and detached from interpersonal bonds,

whether individual, family, or community.

Paradoxically, the

oligarchic interests promoting all this do so behind catchcries of

'brotherhood' and a 'new world order'.

Hence Crowley, like Oscar

Wilde, 35 W.B. Yeats, et al, lamented the destruction of

craftsmanship that proceeded apace after the Industrial Revolution.

One might say prior to that since the mercantile spirit of the

Reformation made economics the master, again in the name of

'freedom'.

Crowley wrote:

Machines have already

nearly completed the destruction of craftsmanship. A man is no

longer a worker but a machine-feeder. The product is

standardized; the result mediocrity…

Instead of every man

and every woman being a star, we have an amorphous population of

vermin. 36

Today, in place of the

machine-feeder there is the data-feeder, while products remain

standardized, including the arts, aggravated by mass

techno-entertainment.

Crowley's vision was that of the Thelemite as Knight fighting every

tyranny that suppressed the human will:

We have to fight for

freedom against oppressors, religious, social or industrial, and

we are utterly opposed to compromise, every fight is to be a

fight to the finish; each one of us for himself, to do his own

will, and all of us for all, to establish the law of Liberty…

Let every man bear

arms, swift to resent oppression… generous and ardent to draw

sword in any cause, if justice or freedom summon him. 37

It seems we still await

the emergence of such Knights of Thelema, although one

suspects that like Yukio Mishima, the modern age Samurai,

these Knights would be quickly liquidated by the weapons of mass

destruction in the hands of religious lunatics, whether

in the name of Jesus, Allah or

YHWH, leaving little

scope for chivalric combat.

Footnotes

-

Richard Spence,

'The Magus was a Spy: Aleister Crowley and the Curious

Connections Between Intelligence and the Occult', New Dawn

105, November-December 2007, 25-30

-

Weishaupt is

listed as a 'saint' in Crowley's Gnostic Catholic mass.

Magick in Theory and Practice, Samuel Weiser, 1984, 430

-

Aleister Crowley,

Magick Without Tears, Falcon Press, 1983, 66

-

Crowley, 1986,

68-69. Crowley also writes here of Masonic 'Christian'

degrees being changed in the USA to enable the initiation of

'Jewish bankers'.

-

Crowley, The

Confessions of Aleister Crowley, Routledge & Kegan Paul,

1986, 697. Rudolf Steiner was also similarly critical of

English Masonry.

-

Crowley, Liber

Legis, Samuel Weiser, 1976, 3:60

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, Falcon Press, 1985, 321

-

Crowley, Magick,

430

-

Friedrich

Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Penguin Books, 1969,

136-138

-

KR Bolton,

'Nietzsche Contra Darwin', in Southgate, ed., Nietzsche:

Thoughts & Perspectives, Vol. 3, Black Front Press, 2011,

5-19

-

Liber Legis, 1: 3

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 175

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 143-145

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 228

-

Friedrich

Nietzsche, Beyond Good & Evil, Penguin, 1984, 175

-

Liber Legis, 2:

58

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 192

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 193

-

Crowley, Liber

CXCIV, 'OTO. An intimation with references to the

Constitution of the Order', para. 10, The Equinox, Vol. III,

No. 1, 1919

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 192

-

Crowley, The Book

of Wisdom or Folly, Samuel Weiser, 1991, Liber Aleph Vel CXI,

De Ordine Rerum, clause 39

-

Julius Evola, Men

Above the Ruins, Inner Traditions, 2002, 224-234

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 251-252

-

Supreme court.

-

Crowley, 'OTO. An

intimation with references to the Constitution of the

Order', para. 21

-

Bolton, Artists

of the Right, Counter-Currents Publishing, 2012, 27-30

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 230

-

Bolton, 'A Secret

History of Money Power', New Dawn Special Issue Vol. 10, No.

2, 55, 58

-

Crowley, Magick

Without Tears, Falcon Press, 1983, 346

-

Bolton, New Dawn,

58

-

Hugh O'Reilly,

'Medieval Work and Leisure',

www.traditioninaction.org/History/A_021_Festivals.htm

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 251

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 192

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 227

-

Oscar Wilde, The

Soul of Man Under Socialism, Black House Publishing, 2012

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 281

-

Crowley, The Law

is for All, 317

|