|

by Wal Thornhill

20 May 2008

from

HoloScience Website

"The conformist propensity

of social institutions is not the only reason that

erroneous theories persevere. However, once embedded

within a culture, ideas exhibit an uncanny inertia, as

if obeying Newton's law to keep on going forever until

acted upon by an external force."

Henry Zemel

"One fact that strikes everyone is the spiral shape of

some nebulae; it is encountered much too often for us to

believe that it is due to chance. It is easy to

understand how incomplete any theory of cosmogony which

ignores this fact must be. None of the theories accounts

for it satisfactorily, and the explanation I myself once

gave, in a kind of toy theory, is no better than the

others. Consequently, we come up against a big question

mark."

Henri Poincaré

at the conclusion of the

preface to his book, Hypothèses Cosmogoniques

"Space is filled with a network of currents which

transfer energy and momentum over large or very large

distances. The currents often pinch to filamentary or

surface currents. The latter are likely to give space,

as also interstellar and intergalactic space, a cellular

structure."

Hannes Alfvén

In an

Electric Universe, X-ray and radio astronomies are very

important.

-

X-ray because it reveals discharge

activity that produces x-rays

-

Radio because it

traces the cosmic power transmission lines in deep space

through the polarization of radio waves from electrons

spiraling in a magnetic field - known as ‘synchrotron

radiation'

The Very Large

Array (VLA) of radio antennae in its most compact configuration

("D-array").

The VLA is 50 miles

west of Socorro, New Mexico on U.S. Highway 60.

Image courtesy of

NRAO/AUI and Kristal Armendariz, Photographer.

A

recent report from the National

Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) highlights the usefulness of

radio astronomy in discovering some of the electrical secrets of

galaxies.

However, it also demonstrates the

"uncanny inertia" of "erroneous theories."

New VLA Images

Unlocking Galactic Mysteries

Astronomers have produced a scientific gold mine of detailed,

high-quality images of nearby galaxies that is yielding important

new insights into many aspects of galaxies, including their complex

structures, how they form stars, the motions of gas in the galaxies,

the relationship of "normal" matter to unseen "dark matter," and

many others.

An international team of scientists used

more than 500 hours of observations with the National Science

Foundation's Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope to produce

detailed sets of images of 34 galaxies at distances from 6 to 50

million light-years from Earth.

Their project, called The HI Nearby

Galaxy Survey, or THINGS *, required two years to produce nearly

one TeraByte of data.

* The

THINGS project is a large

international collaboration led by Fabian Walter of the Max-Planck

Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, and includes

research teams led by Brinks, de Blok, Michele Thornley of the

Bucknell University in the U.S. and Rob Kennicutt of the Cambridge

University in the UK. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a

facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under

cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

HI ("H-one") is an astronomical term for

atomic hydrogen gas.

"Studying the radio

waves emitted by atomic hydrogen gas in galaxies is an extremely

powerful way to learn what's going on in nearby galaxies."

Comment

The reference to "dark matter" in the

outline of the THINGS project should be of concern to all taxpayers.

The invention of undetectable

"dark"

matter in a gravitational model of galaxies should be ringing alarm

bells and flashing warning lights for anyone with commonsense.

It is

saying that there may be something we don't know about gravity or

that simple Newtonian mechanics does not apply to galaxies. Perhaps

both are true. Clearly, we need a better explanation than "an

invisible tooth fairy did it."

To be confident we understand galaxies

we need a working model that can be demonstrated in the laboratory.

Is there such a model?

The Electric

Galaxy

The scandalous truth is that there is a model of spiral galaxy

formation that has long been demonstrated by laboratory experiment

and "particle in cell" (PIC) simulations on a supercomputer.

But instead of using stars, gas and dust

as the particles, subject to Newton's laws, the particles are

charged and respond to the laws of electromagnetism.

This seems like an obvious approach when

we know that more than 99.9 percent of the visible universe is

in the form of plasma. Plasma is a gas influenced by the

presence of charged atoms and electrons. Plasma responds to

electromagnetic forces that exceed the strength of gravity to the

extent that gravity can usually be safely ignored.

This simple fact alone suggests why

gravitational models of galaxies must fail.

The plasma universe

may be eternal and infinite, directly contradicting the

Big Bang model.

In this picture,

swirling streams of electrons and ions form filaments

that span vast regions of space. Where pairs of these

filaments interact the particles gain energy and at

narrow "pinch" regions produce the entire range of

galaxy types as well as the full spectrum of cosmic

electromagnetic radiation.

Thus galaxies must

lie along filaments, as they are observed to do on a

large scale. The bulk of the filaments are optically

invisible from a distance, much like the related

Birkeland currents that reach from the Sun and cause

auroras on Earth.

Credit: A. Peratt,

Plasma Cosmology, 1992.

The simplest geometry for galaxy

formation is two adjacent

Birkeland currents of width 35

kiloparsecs

separated by 80 kiloparsecs.

The interaction region, and hence the

thickness of a galaxy is 10 kpc. By scaling the current flows in

astronomical objects by size, it is determined that the average flow

in a galactic Birkeland current is approximately 1019 amperes; the Alfvén galactic current.

The synchrotron radiated power is of the

order of 1037 watts, that is, the power recorded from double radio

galaxies.

These images from a

supercomputer simulation trace the development of spiral

structure in two interacting plasma blobs over a span of

nearly 1 billion years. At the start of the interaction

at upper left the filaments are 260,000 light-years

apart; all 10 panels are reproduced at the same scale.

Simulations such as this can reproduce the full range of

observed spiral galaxy types using electromagnetic

processes rather than gravitational ones.

Credit: A. Peratt,

Plasma Cosmology, 1992.

And so that there can be no objection,

the computer simulations have been backed up by experiments in the

highest energy density laboratory electrical discharges - the

Z-pinch machine.

The experiments verify each stage in

development of the PIC simulations.

This important work demonstrates that

the beautiful spiral structure of galaxies is a natural form of

plasma instability in a universe energized by electrical power.

Electrical

discharges (Lichtenberg figures) illuminate the surface

of the Z-machine during a recent shot. The most recent

advance gave an output power of about 290 trillion watts

for billionths of a second, about 80 times the entire

world's output of electricity focused onto a target the

size of a cotton reel.

NOTE:

Clearly, the

production of a spiral galaxy requires the input of

prodigious electrical power!

But nowhere in

astrophysical theory will you find any mention of

electrical energy. In stark contrast, cosmologists are

content to invent "dark matter" and "dark energy" on the

basis of their universe built with the weakest force in

the universe - gravity.

Meanwhile magnetic

fields are found throughout space, plainly signaling the

electric currents required to sustain them.

Most of the

galaxies studied in the THINGS survey also have been

observed at other wavelengths, including Spitzer space

telescope infrared images and GALEX ultraviolet images.

This combination

provides an unprecedented resource for unraveling the

mystery of how a galaxy's gaseous material influences

its overall evolution.

Analysis of THINGS data already has yielded numerous

scientific payoffs. For example, one study has shed new

light on astronomers' understanding of the gas-density

threshold required to start the process of star

formation.

"Using the data

from THINGS in combination with observations from

NASA's space telescopes has allowed us to

investigate how the processes leading to star

formation differ in big spiral galaxies like our own

and much smaller, dwarf galaxies," said Adam Leroy

and Frank Bigiel of the Max-Planck Institute for

Astronomy at the Austin AAS meeting.

Because atomic

hydrogen emits radio waves at a specific frequency,

astronomers can measure motions of the gas by noting the

Doppler shift in frequency caused by those motions.

"Because the

THINGS images are highly detailed, we have been able

to measure both the rotational motion of the

galaxies and non-circular random motions within the

galaxies," noted Erwin de Blok of the University of

Cape Town, South Africa.

Comment

The observations of ‘motions of gas' in

galaxies will be valuable to plasma cosmologists but will only serve

to further confuse gravity models because it is not 'gas' that is in

motion but plasma.

And as for star formation, the same

electrical plasma processes that form galaxies are involved at the

stellar scale. A later article will show that astronomers'

understanding of stars is little advanced on the aboriginal

‘campfire in the sky.'

There will be no new light on

astronomers' understanding of stars until electric light dispels the

darkness.

Comparison of

rotational velocity with radius in a spiral galaxy

versus a supercomputer simulation of the rotation of an

equivalent mass object formed at the intersection of two

interacting plasma filaments. No dark matter need be

invented to reproduce the peculiar rotation curves of

spiral galaxies because the electromagnetic forces

acting on plasma are so much stronger than gravity.

Credit: A. Peratt.

There is an important lesson here.

The notion that gravity governs

celestial mechanics has been "embedded within our culture" for

hundreds of years and is as difficult to dislodge as was Ptolemy's

epicycles. Science is essentially a cultural activity and is not as

objective as we like to fool ourselves. It seems that the cultural

imperative remains strong enough to deny prima facie evidence and

defy logic and commonsense.

As Max Planck lamented,

"An important

scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning

over and converting its opponents. What does happen is that its

opponents gradually die out, and that the growing generation is

familiarized with the ideas from the beginning."

But our growing generation is not being

familiarized with important scientific innovation, that history

shows often comes from outsiders to a discipline who have not been

imbued with the culture of that discipline.

Innovation from outside a discipline is

actively suppressed by academia and generally ignored by a

lazy media. Meanwhile there is a

blizzard of high-tech computer simulations ** presented to a growing

generation as real science.

** The PIC supercomputer

simulations referred to earlier are simply based on the known

behavior of charged particles obeying Maxwell's laws of

electromagnetism. So it is no surprise that the simulations mimic

the lab results. However, most cosmological simulations are derived

from a priori mathematical theory where there are no experiments or

direct observations to serve as a brake on speculation. The result

is continual astonishment at new data.

Science has entered the age of virtual

reality.

And our understanding of the universe

has become as contrived as a computer game.

The new survey also

showed a fundamental difference between the nearby

galaxies - part of the "current" Universe, and far more

distant galaxies, seen as they were when the Universe

was much younger.

"It appears

that the gas in the galaxies in the early Universe

is much more 'stirred up,' possibly because galaxies

were colliding more frequently then and there was

more intense star formation causing material

outflows and stellar winds," explained Martin Zwaan

of the European Southern Observatory. The

information about gas in the more distant galaxies

came through non-imaging analysis. These

discoveries, the scientists predict, are only the

tip of the iceberg. "

This survey

produced a huge amount of data, and we've only analyzed

a small part of it so far.

Further work is

sure to tell us much more about galaxies and how they

evolve. We expect to be surprised," said Fabian Walter,

of the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg,

Germany.

Comment

The expectation of surprise has become a

hallmark of astronomy.

It is symptomatic of the non-predictive

nature of astrophysical theory based on the big bang and

gravitational cosmology. Successful prediction is the principal test

of a good theory, not surprises.

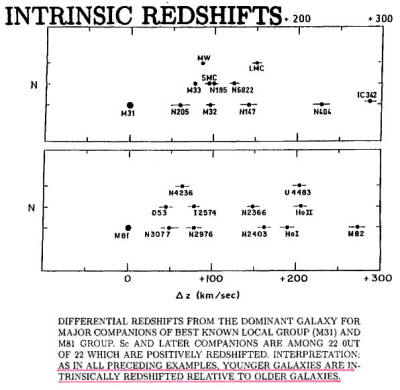

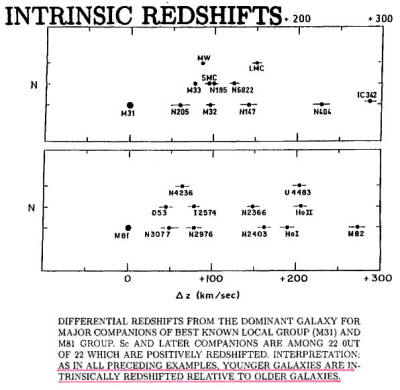

In the Electric Universe, the lynchpin of big bang theory - the

equation of

redshift of stellar spectra with velocity of recession -

is shown empirically to be false.

The inability of astrophysicists

to accept the manifest evidence of intrinsic redshift (below image -

a high-redshift quasar in front of a low redshift galaxy should be

blatant enough) may be due to a reluctance to admit that modern

physics has no explanation for the phenomenon of mass in matter and

therefore cannot explain how subatomic particles like the proton and

electron might exhibit the lower mass required to produce lower

energy spectra (redshift).

Observations of connections between

high- and low-redshift objects requires that the redshift is

intrinsic to the matter in distant quasars and galaxies and cannot

be due to some modification of the light on its journey to Earth.

It calls into question our understanding

of quantum theory because it has been discovered that the redshift

of quasars and companion galaxies is quantized!

Quantum theory has no real explanation, it is merely a set of rules

that match some limited real world observations. On that basis it is

a very shaky pillar to support cosmology.

Quantum theory is thought

to apply exclusively to the submicroscopic realm of atoms and

subatomic particles. But that is not so.

Redshift has been observed to be

quantized across entire galaxies - no galaxy has been found in

transition from one redshift to another.

Intrinsic redshift of quasars and galaxies means an end to the big

bang. Instead of being seen "when the universe was much younger,"

highly redshifted objects are merely young, nearby and faint.

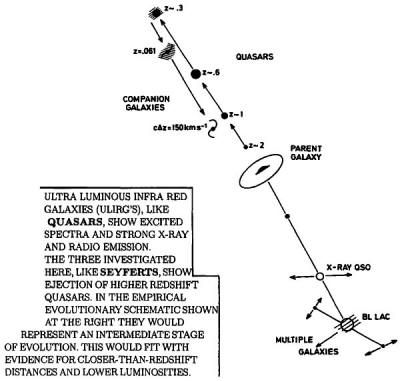

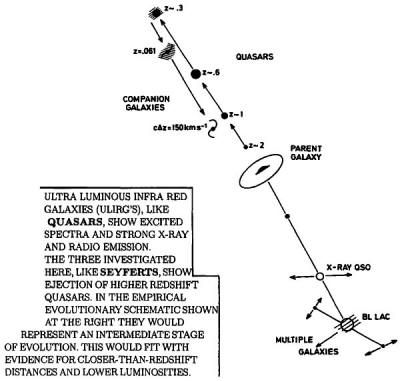

Observations show that quasars are

"born" (below image) from the nucleus of active galaxies.

They initially move very fast away from

their parent, usually roughly along the spin axis.

As they grow older they grow brighter

and seem to slow down as they gain in mass and evolve into companion

galaxies.

This gain in massiveness points to a

process whereby normal matter can pass through a number of small

quantized increases in mass, which gives rise to the observed

quantized decreases in redshift. This discovery points the way, at

last, to an understanding of the phenomenon of mass.

The "stirred up" gas in highly redshifted objects can be simply

understood as being due to unruly youthfulness and electrical

hyperactivity. It has nothing to do with an imaginary early epoch of

galactic collisions.

In fact, "galactic collisions" are a

recently popular catch-all to try to explain the formation of spiral

galaxies and many of their anomalous features. Collisions are as

unlikely and unnecessary as they are forbidden in

an Electric

Universe.

The following exceptional example clearly favors the

Electric Universe explanation.

One simple electrical model fits all

galaxies naturally.

A nearly perfect

ring of hot, blue stars pinwheels about the yellow

nucleus of an unusual galaxy known as

Hoag's Object.

This image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope captures a

face-on view of the galaxy's ring of stars. The entire

galaxy is about 120,000 light-years wide, which is

slightly larger than our Milky Way Galaxy.

Ring-shaped

galaxies can form in several different ways. One

possible scenario is through a collision with another

galaxy. Sometimes the second galaxy speeds through the

first, leaving a ‘splash' of star formation. But in Hoag's

Object there is no sign of the second galaxy, which

leads to the suspicion that the blue ring of stars may

be the shredded remains of a galaxy that passed nearby.

Some

astronomers estimate that the encounter occurred about 2

to 3 billion years ago."

Image Credit: NASA

and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Acknowledgment: Ray

A. Lucas (STScI/AURA)

Comment

In stark contrast to standard ad hoc

attempts to explain Hoag's object in terms of a collision, the

Electric Universe can point to a simple explanation, which fits

neatly the plasma cosmology model of formation of galaxies in a

magnetic pinch at the intersection of cosmic Birkeland current

filaments.

Hoag's object shows the detailed

features of the ‘penumbra' of a plasma focus discharge.

Penumbra of a dense

plasma focus from a discharge current of 174,000

amperes. The rotational structure of the penumbra has a

periodicity of 56 as shown by the 56-dot overlay

pattern.

Credit A. Peratt.

See also the earlier image of the active

galactic nucleus of

NGC 1097 as another fine example of a dense

plasma focus penumbra. The astronomer Halton Arp has shown that NGC

1097 is one of the most compelling examples of quasar ejection from

an active nucleus.

He describes it as "a busy quasar

factory."

The plasma focus is

the simplest of devices. Two coaxial cylindrical

electrodes have a very high voltage and current applied

between them at one end. A radial discharge is initiated

(shown in blue), which moves axially along the

electrodes (1), under the influence of its

self-generated magnetic field, until it reaches the end

of the electrodes. There it balloons out in a

filamentary penumbra (2).

Image credit: E.

Lerner

The Birkeland current filaments are

caused by the magnetic pinch effect and they space themselves evenly

apart in a characteristic number of 56 filaments.

With time, the 56 filaments coalesce in

two's and sometimes threes. The result is a sequence of 56 (by far

the most common), 49, 47, 41, 39, 33, 30, followed by a large number

of 28 filaments. The convergence continues through 20, 16, 8, 7, 6,

and 4, the latter being the minimum number of Birkeland filaments

recorded.

The energy of the discharge becomes focused at the center of the

inner electrode (3) where a ‘kink' plasma instability causes the

filaments to form a ‘coiled coil' like a coiled telephone cord.

The kink instability twists upon itself

to form a tiny donut shaped ‘plasmoid' of extremely high

energy density.

Eventually, the plasmoid breaks down and

electrons and ions are accelerated from the plasmoid in opposite

directions along the axis in intense, narrow beams (4).

The above

left hand image

shows the kink instability at the dense plasma focus.

The right hand image shows the form of the plasmoid and

the particle jets created when the magnetic field begins

to collapse.

Image credit: E.

Lerner

The natural formation of highly focused

jets from some stars and active galactic nuclei is now clear.

And the rapid motion of stars close to

our own galactic center may be explained by the assemblage of matter

there in the form of a dusty plasmoid constrained by powerful

magnetic fields.

Below is an image of the galactic jet of M87 with (by way of

contrast) the best explanation that gravitational theorists can

muster.

The jet blasting

out of the nucleus of M87, a giant elliptical galaxy 50

million light years away in the constellation Virgo

[false color]. At the extreme left of the image, the

bright galactic nucleus harboring a supermassive black

hole shines.

The jet is thought

to be produced by strong electromagnetic forces created

by matter swirling toward the supermassive black hole.

These forces pull

gas and magnetic fields away from the black hole along

its axis of rotation in a narrow jet. Inside the jet,

shock waves produce high-energy electrons that spiral

around the magnetic field and radiate by the

"synchrotron" process, creating the observed radio,

optical and X-ray knots.

Comment

The gravitational ‘explanation' of the

galactic jet can be summarized in one word - "garbage."

The confident assertion that the

galactic nucleus is hiding a supermassive black hole is nonsense.

Black holes are a ‘school-kid

howler' perpetrated by top scientists. It involves taking Newton's

gravitational equation to an absurd limit by dividing by zero to

achieve an almost infinitely powerful gravitational source. This is

done by impossibly squeezing the matter of millions of stars into

effectively a point source.

And then mysteriously available magnetic

fields are pressed into performing miracles to create something that

approximates a relativistic jet of matter from an object that is

supposed to gobble up anything that comes near.

It is very disturbing that the public accepts this blatant baloney

without question.

If scientists were forced to defend

their statements in a court of law under the rules of evidence, most

of the misbegotten ideas that make up modern science would never

have survived. Physics would have remained in the classical hands of

the experimentalists and the engineers who have to make things work.

Countless billions of dollars could have

been saved in misdirected and pointless experiments.

The experimental evidence for the electrical nature of galaxies has

been available for many decades now. But who has heard anything

about it? The lack of debate demonstrates the power of

institutionalized science to maintain the "uncanny inertia" of the "erroneous theories" they have introduced into our culture. We have

given scientists that power by trusting them more than our

commonsense.

Having discovered electric power we find it indispensable. We also

find that Nature does things with exquisite economy.

So the commonsense question is simply,

"Would Nature choose

the weakest force in the universe - gravity - to form and light

the countless magnificent galaxies?"

I don't think so!

|