|

by Brandon Keim

April 17, 2009

from

WiredScience Website

For scary speculation about the end

of civilization in 2012, people usually turn to followers of

cryptic Mayan prophecy, not scientists.

But thatís exactly what a group of

NASA-assembled researchers described in a chilling report issued

earlier this year on the destructive potential of solar storms.

Entitled "Severe

Space Weather Events - Understanding Societal and Economic Impacts,"

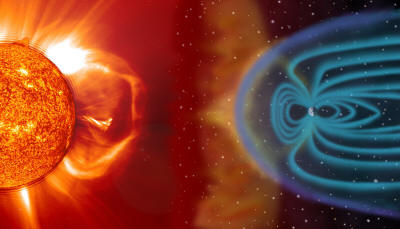

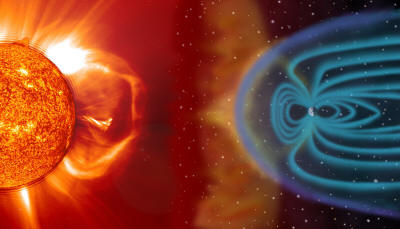

it describes the consequences of solar flares unleashing waves of

energy that could disrupt Earthís magnetic field, overwhelming

high-voltage transformers with vast electrical currents and

short-circuiting energy grids.

Such a catastrophe would cost the United

States "$1 trillion to $2 trillion in the first year," concluded the

panel, and "full recovery could take 4 to 10 years." That would, of

course, be just a fraction of global damages.

Good-bye, civilization.

Worse yet, the next period of intense solar activity is expected in

2012, and coincides with the presence of

an unusually large hole in Earthís

geomagnetic shield. But the report received relatively little

attention, perhaps because of 2012ís supernatural connotations.

Mayan astronomers supposedly predicted that 2012 would mark the

calamitous "birth of a new era."

Whether the Mayans were on to something, or this is all just a

chilling coincidence, wonít be known for several years.

But according to Lawrence Joseph,

author of "Apocalypse

2012 - A Scientific Investigation into Civilizationís End,"

"Iíve been following this topic for

almost five years, and it wasnít until the report came out that

this really began to freak me out."

Wired.com talked to Joseph:

Wired.com: Do you think itís coincidence that the

Mayans predicted apocalypse on

the exact date when astronomers say the sun will next reach a

period of maximum turbulence?

Lawrence Joseph: I have enormous respect for Mayan astronomers.

It disinclines me to dismiss this as a coincidence. But I

recommend people verify that the Mayans prophesied what people

say they did. I went to Guatemala and spent a week with two

Mayan shamans who spent 20 years talking to other shamans about

the prophecies. They confirmed that the Maya do see 2012 as a

great turning point. Not the end of the world, not the

great off-switch in the sky, but the birth of the fifth age.

Wired.com: Isnít a great off-switch in the sky exactly whatís

described in the report?

Joseph: The chair of the NASA workshop was Dan Baker at

the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics. Some of

his comments, and the comments he approved in the report, are

very strong about the potential connection between

coronal mass ejections and

power grids here on Earth. Thereís a direct relationship between

how technologically sophisticated a society is and how badly it

could be hurt. Thatís the meta-message of the report.

I had the good fortune last week to meet with John Kappenman

at

MetaTech. He took me

through a meticulous two-hour presentation about just how

vulnerable the power grid is, and how it becomes more vulnerable

as higher voltages are sent across it. He sees it as a big

antenna for space weather outbursts.

Wired.com: Why is it so vulnerable?

Joseph: Ultra-high voltage transformers become more finicky as

energy demands are greater. Around 50 percent already canít

handle the current theyíre designed for. A little extra current

coming in at odd times can slip them over the edge.

The ultra-high voltage transformers, the 500,000- and

700,000-kilovolt transformers, are particularly vulnerable. The

United States uses more of these than anyone else. China is

trying to implement some million-kilovolt transformers, but Iím

not sure theyíre online yet.

Kappenman also points out that when the transformers blow,

they canít be fixed in the field. They often canít be fixed

at all. Right now thereís a one- to three-year lag time between

placing an order and getting a new one.

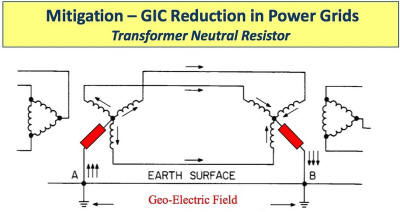

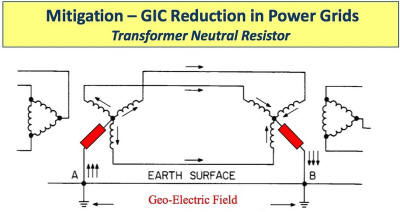

According to Kappenman, thereís an as-yet-untested plan for

inserting ground resistors into the power grid. It makes the

handling a little more complicated, but apparently isnít

anything the operators canít handle. Iím not sure heíd say these

could be in place by 2012, as itís difficult to establish

standards, and utilities are generally regulated on a

state-by-state basis.

Youíd have quite a legal thicket.

But it still might be possible to get some measure of protection

in by the next solar climax.

Wired.com: Why canít we just shut down the grid when we see a

storm coming, and start it up again afterwards?

Joseph: Power grid operators now rely on

one satellite called ACE, which

sits about a million miles out from Earth in whatís called the

gravity well, the balancing point between sun and earth. It was

designed to run for five years. Itís 11 years old, is losing

steam, and there are no plans to replace it.

ACE provides about 15 to 45 minutes of heads-up to power plant

operators if somethingís coming in. They can shunt loads, or

shut different parts of the grid. But to just shut the grid off

and restart it is a $10 billion proposition, and there is lots

of resistance to doing so. Many times these storms hit at the

north pole, and donít move south far enough to hit us. Itís a

difficult call to make, and false alarms really piss people off.

Lots of money is lost and damage incurred.

But in Kappenmanís view, and in lots

of others, this time burnt could really mean burnt.

Wired.com: Do you live your life differently now?

Joseph: Iíve been following this topic for almost five years. It

wasnít until the report came out that it began to freak me out.

Up until this point, I firmly believed that the possibility of

2012 being catastrophic in some way was worth investigating. The

report made it a little too real. That document canít be

ignored. And it was even written before the

THEMIS satellite discovered a gigantic

hole in Earthís magnetic shield. Ten or twenty times

more particles are coming through this crack than expected. And

astronomers predict that the way the sunís polarity will flip in

2012 will make it point exactly the way we donít want it to in

terms of evading Earthís magnetic field.

Itís an astonishingly bad set of

coincidences.

Wired.com: If Barack Obama said, "Letsí prepare," and there

werenít any bureaucratic hurdles, could we still be ready in

time?

Joseph: I believe so. Iíd ask the President to slipstream behind

stimulus package funds already appropriated for smart grids,

which are supposed to improve grid efficiency and help transfer

high energies at peak times. Thereís a framework there. Working

within that, you could carve out some money for the ground

resistors program, if those tests work, and have the initial

momentum for cutting through the red tape. Itíd be a place to

start.

Wired.com talked to John

Kappenman, CEO of electromagnetic damage consulting company

MetaTech, about the possibility of geomagnetic apocalypse ó and how

to stop it.

Wired.com: Whatís the problem?

John Kappenman: Weíve got a big, interconnected grid that spans

across the country. Over the years, higher and higher operating

voltages have been added to it. This has escalated our

vulnerability to geomagnetic storms. These are not a new thing.

Theyíve probably been occurring for as long as the sun has been

around.

Itís just that weíve been unknowingly building an

infrastructure thatís acting more and more like an antenna for

geomagnetic storms.

Wired.com: What do you mean by

antenna?

Kappenman: Large currents circulate in the network, coming up

from the earth through ground connections at large transformers.

We need these for safety reasons, but ground connections provide

entry paths for charges that could disrupt the grid.

Wired.com: Whatís your solution?

Kappenman: What weíre proposing is to add some fairly small and

inexpensive

resistors in the transformersí ground connections.

The addition of that little bit of resistance would

significantly reduce the amount of the geomagnetically induced

currents that flow into the grid.

Wired.com: What does it look like?

Kappenman: In its simplest form, itís something that might be

made out of cast iron or stainless steel, about the size of a

washing machine.

Wired.com: How much would it cost?

Kappenman: Weíre still at the conceptual design phase, but we

think itís do-able for $40,000 or less per resistor. Thatís less

than what you pay for insurance for a transformer.

Wired.com: And less than what youíd willingly pay for

insurance on civilization.

Kappenman: If youíre talking about the United States, there are

about 5,000 transformers to consider this for. The

Electromagnetic Pulse Commission

recommended it in a report they sent to Congress last year.

Weíre talking about $150 million or so. Itís pretty small in the

grand scheme of things.

Big power lines and substations can withstand all the other

known environmental challenges. The problem with geomagnetic

storms is that we never really understood them as a

vulnerability, and had a design code that took them into

account.

Wired.com: Can it be done in time?

Kappenman: Iím not in the camp thatís certain a big storm will

occur in 2012. But given time, a big storm is certain to occur

in the future. They have in the past, and they will again.

Theyíre about one-in-400-year events. That doesnít mean it will

be 2012. Itís just as likely that it could occur next week.

|