|

by Manuel Rosa

September 23, 2021

from

Ancient-Origins Website

|

Manuel Rosa is a PhD candidate in Insular and Atlantic

History (15th-20th Centuries) at the University of the

Azores.

He

has spent 30 years investigating the life of the

discoverer, took part in DNA testing and advised UNESCO

and the Haitian Government on matters of Colón's lost

ship

the

Santa Maria.

Several of his books published on this subject include

COLUMBUS - The Untold Story (Outwater Media, 2016) and

Portugal e o Segredo de Colombo (Alma dos Livros, 2019).

His

webpage is located at

www.Manuel-Rosa.com. |

Was the fleet of Santa Maria, Pinta and Niña

represented here admiral led by

Christopher Columbus

or Don Cristóbal Colón?

Source: Michael Rosskothen / Adobe Stock

The news was astounding!

Famous India was

discovered just a month's sailing across the Atlantic,

proclaimed the first-ever International Press Release, dated

Lisbon, March 4, 1493...

The outrageous assertion

addressed to Luis de Santángel (clerk of Ración de la Corona

de Aragón,) begins,

"Sir: Since I know

that you will rejoice with the glorious success that our Lord

has given me in my voyage, I write this to tell you that in 33

days I sailed to the Indies," wrote Don Cristóbal Colón, the

newly created Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Viceroy and Governor of

the Indies.

Commonly known today as

Colón's First Letter, the published newsflash was so

extraordinary that it spread like wildfire amongst the population of

Europe.

You may have never heard of the noble knight named Don

Cristóbal Colón that discovered the New World on October 12,

1492, because historians gave the discovery fame to another man.

The man historians chose

was Cristoforo Colombo, a peasant weaver from Genoa, Italy,

whom the English call by the Latinized name of Christopher Columbus.

Inspiration de Cristobal Colón

by Jose

Maria Obregon, 1856.

(CC

BY-SA 3.0)

What's In A

Name: Columbus's Mistaken Identity

For the last 100 years, Italians have celebrated their Genoese

Christopher Columbus, and professors still teach this

Christopher Columbus fairytale in schools all around the globe.

Historians mixed up the

noble navigator Colón with the peasant weaver Colombo, giving the

wool-weaver the glory that did not belong to him.

Contemporary documents

prove that the Genoese weaver Christopher Columbus was not the

explorer Don Cristóbal Colón. The investigation of the

documents by this author is published in COLUMBUS-The Untold Story.

How did such a mistake come to be?

It was not just a simple

case of mistaken identity...

How Mistakes

Lead to Mistaken Identity

To understand how researchers took the wrong road to Genoa, we must

recognize the labyrinth of misinformation created initially by the

printing press in 1493.

Also imperative to this

story is a 30-year-long Spanish Inheritance Lawsuit initiated in

1578.

Aside from the false news

published in the European Press of the day, forged documents were

introduced during the Inheritance Lawsuit to support the Genoese

Christopher Columbus.

As soon as Admiral Colón anchored in Lisbon on March 4, 1493, he

sent the now-famous letter to Santángel who, not only helped

to convince Queen Isabel to sponsor him, but had lent money to the

Spanish Crown to finance the 1492 voyage.

It is not clear how the

Barcelona printer Pedro Posa managed to get his hands on the

missive sent to Santángel. Still, during its printing Posa gave the

discoverer the surname of Colom.

Posa's final sentence

reads,

"This letter was sent

by Colom to the Escrivano de Ración about the islands discovered

in the Indies, contained in another letter to Their Highnesses,"

(Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Second

page of the Barcelona Letter printed in April 1493 by Pedro Posa,

ending

with, "This letter sent Colom..." Colom means pigeon in Catalan.

( The

New York Public Library )

This minor misspelling by Posa was probably an innocent mistake.

Using an m instead of an

n was the first misinformation step. A more considerable error arose

just a few weeks later when Posa's publication was translated by

Aliander de Cosco into Latin and republished in Rome on April 29,

1493.

This Roman news pamphlet

further corrupted the name Colom into Columbo, gaining the infamy of

being the first publication to give the false name of Columbo to

Colón, as shown in Figure 2.

Ever since Cosco's 1493 publication, the mistake of changing Colón

into Colombo spread to all non-Spanish-speaking nations.

Colón's propaganda letter

was such a sensation that eleven editions were published in 1493

alone. Between 1494 and 1497, six more editions were published,

spreading the news of the discovery to the four corners of Europe.

The unaware public never

knew they were being communicated false information.

Figure 2.

Section

of the First Letter printed in Rome,

showing

the printing error of the name as "Columbo."

(Source: Library of Congress,

Control

Number: 46031077)

Those who contended that the navigator's surname was Colombo were

people outside of Spain, living far from the events and alien to the

truth.

Hence all places outside

Spain started to know Admiral Colón by the wrong name of

Colombo/Columbus.

However, Colombo and

Columbus were not the only wrong versions of the Admiral's

surname...

Various publications show

no agreement on the surname with variations such as,

Christofori Colom,

Christophorum Coloni, Christoforo Colûbo, Christophoro Colõbo,

Christofano Colombo, Xpõfano Cholonbo,

...among others... see

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Various

versions of Colón's letter

where

the name appears according to

the

printer's taste.

(Author

compilation)

This false portrayal of the mastermind of the epic voyage as Columbo

instead of Colón was a mistake that grew and grew over the centuries

and tricked historians into investigating and writing about the

wrong person.

The error continued until the present day and has been impossible to

correct.

The Voyage

from Colón to Columbus

We can now comprehend how from 1493 until today the media, (authors,

printers and translators,) have been altering the facts about

Admiral Colón's life.

First, they distorted

the name of Colón to Colom in Catalan, and then to

Columbo, Columbus, Colombo, Kolomb,

and so on...

The rest, as they

say, is history, albeit erroneous.

Had Cristóbal Colón's

voyage taken place just a few decades earlier, before the

establishment of the printing press, he would not have garnered so

much worldly fame, and less confusion would have been created around

his identity.

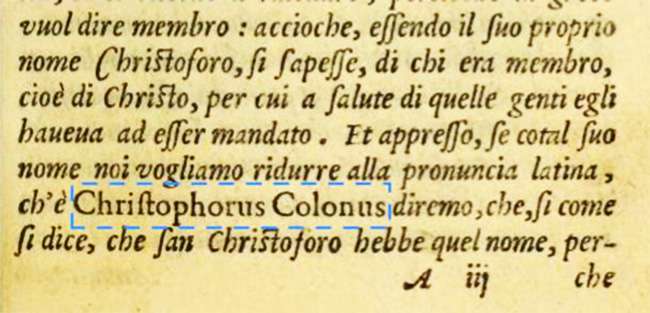

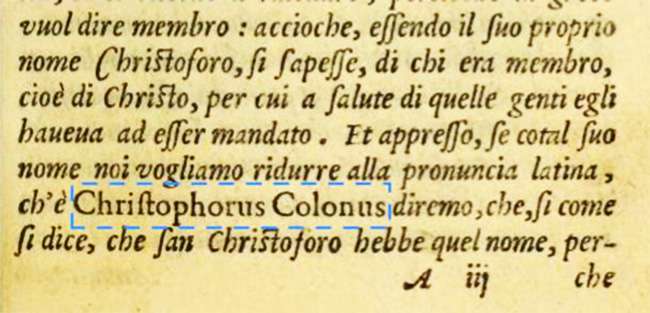

Don Hernando Colón, Don Cristóbal's son, wrote in his

Historie that the Latin form of his father's name was Christopher

Colonus, thus, not Columbus – see Figure 4.

This explanation was

necessary because countless people were already calling his father

by the wrong name during Hernando's lifetime. Don Hernando even

explained that the name Colón came from the Greek kōlon, meaning

member in that language.

The same word where the

English language got its colon and semicolon from.

Figure 4.

Page 3

of Don Hernando's Historie

where

he wrote Christopher Colonus.

(Internet Archive)

Contrary to the

Portuguese language, where Colom corresponds to a Portuguese

form of the Spanish Colón, unfortunately, the word colom in

Catalan means pigeon.

The Catalan colom

in Posa's printing is equivalent to the Italian colombo and

the Latin columbus, which are not the same as the Greek

kōlon.

Nevertheless, historians insisted, contrary to Hernando's

clarifications and many of Cristóbal Colón's own documents, that his

name was Colombo with the meaning of pigeon in Italian.

Aside from discounting

Don Hernando's statements, the researchers asserted continuously and

incorrectly that Hernando had lied about this father's name and

identity.

They even named him

falsely Hernando Colombo when printing his Historie in 1571.

The Spanish documents show that the correct name is Cristóbal Colón,

never Colombo. Colón is the surname the discoverer used while living

in Spain - see Figure 5.

Colón has been the name

for him and his descendants in Spain and all Spanish-speaking

nations for 530 years.

Colón is the surname by

which his Spanish descendants are presently known.

Figure 5.

The

title page from Don Cristóbal Colón's Book of Privileges

prepared by the discoverer in 1502 reads Cartas Previlegios Cedulas

y otras

Escrituras de Dõ Xpõval Colon

Almirãte Mayor del Mar Oceano Visorey y Governador de las Islas y

Tierrra Firme

[Letters, Grants, Bonds and other Documents of D. Cristóbal Colón,

Admiral

Major of the Atlantic, Viceroy and Governor of the Islands and

Continent.]

(Source: University of North Carolina at Chapell Hill,

Rare

Books Collection, RBC folio E114.S84c.1.)

Obscuring the

Truth

Many authors, including those of the Raccolta Colombiana,

used the names Colón and Colombo indiscriminately and

interchangeably as if they were the same name.

Treating both surnames as

the same caused even more confusion.

They would certainly not

have done so innocently, but to remove obvious doubts that exposed

the Genoese weaver as not being the Iberian navigator.

"Not a single

document from the Raccolta proves the Italian origin of Colón or

clarifies the mystery of his birth and childhood," declared

Ezquerra Abadía in 1966, and we totally concur.

Contemporary Spanish

writers who knew the navigator in person referred to him as Colom

or Colon.

For example,

"Don Christoual Colom

was the first discoverer and Admiral of these Indies," wrote

Oviedo (1478-1557) at the beginning of his second book Historia

general de las Indias. Andrés Bernáldez (1450-1513), in his

Historia de los Reyes Catholics Don Fernando y Doña Isabel wrote

"whom they called Christobal Colon, a man of very high

ingenuity."

Pedro Matire de

Anghiera, the chaplain to Queen Isabel, wrote "Cristophorus

Colonus" in his book De orbe nouo …

Colón in Spanish is not a translation of the Italian word Colombo,

which is palomo in Spanish.

The merging of the two names into one happened either because

biographers wrongly accepted the two as the same person, or possibly

because it is evident that they were not the same person and some

authors were intent in falsifying the story, just as they have.

This fact caused Afonso Dornelas to write that,

"Colón certainly

never imagined that confusion could arise between Colombos and

Colóns."

This grave translation

error, however, continues to be accepted today and has proven to be

impossible to correct.

For instance, when trying

to translate the Latin word columbus into Spanish, dictionaries give

us Colón and not palomo. In the same way, when we search for the

translation of Colón into English, Lithuanian or any other language,

we get the mistranslation as,

Columbus, Kolumbas,

Kolumb, Colomb, Colombo,

...just to mention a few,

and not the Greek κῶλον nor the Latin colon.

Today, it is clear that the discoverer's name was not Colombo but

Colón and that he was not the Colombo weaver from Genoa.

Still, how could

researchers accept and graft the Colombo weaver into Colón's story?

Portrait of a Man,

said

to be Christopher Columbus

by Sebastiano del Piombo (1485-1547)

(Public Domain)

Columbus Lies,

Double-Dealings, and Forgeries

The false propaganda and rumors had a way to overwhelm the truth.

Yet Colombo families

in Genoa did not believe they were related to the famous

Colón from Spain.

In 1578, when Colón's great-grandson, Don Diego Colón, died without

an heir, all the discoverer's great-grandchildren fought for the

posts, titles, real estate, gold, and lands, some of which were

considerable territories in the New World.

This inheritance lawsuit

lasted until 1609... 30 years of litigation

When the Italian Colombo families learned of this inheritance, some

decided to try and steal it for themselves. However, since they were

not related to the Spanish Colón family, they needed to forge

documents to present to the Spanish Tribunal.

The forgeries were not

only done by the Colombo pretenders but also by the Genoese

government itself in the attempt to inherit what would be, perhaps,

the wealthiest inheritance at the time:

In 1582, arrived Don

Baltazar Colombo, Lord of Cuccaro in Italy, in Monferrato, but

residing in Genoa. In 1588, another Italian, Don Bernardo

Colombo, arrived...

But this litigator

was forced to withdraw because it was demonstrated during the

litigation the falsity of the documents on which his claim was

based.

(GANDÍA,

Pg 52)

In the 1580s, not one

Colombo was found in Genoa who believed himself related to the Colón

family from Spain.

Bernardo Colombo,

one false pretender who fought for the opportunity to be named the

heir to the Spanish House of Colón, was from Cogoleto and not

Genoa.

The other false pretender, Baltazar Colombo was a nobleman who could

afford to prepare a better deception. But he too failed to prove

that Colón was a noble Italian, not from Genoa, but from Baltazar's

land of Cuccaro.

Baltazar supported the defense of his cause through purchased

witness testimony, including a monk who claimed under oath to

remember the birth of the Colón brothers in the Castle of Cuccaro.

Knowing that Admiral

Colón was born circa 1455 and that the monk's testimony was written

around 1580,

how could he swear

that he remembered something that had happened 125 years

earlier...?

Nevertheless, this second

Genoese pretender persevered and fought for Colón's inheritance for

nearly three decades.

With so much

documentation forged in the lawsuit, it became difficult for the

judges of the Tribunal to decipher where the truth was.

Still, lucidity

persevered, as the transcripts from the lawsuit show:

Notoriously excluded

[...] is the aforementioned Don Baltazar [Colombo], for not

belonging, as he claimed to belong, to the same family of the

[...] founder [Don Cristóbal Colón] [...]

Don Baltazar is not,

nor proved to be, a relative of the founder [...] [the 1498 Last

Will that he presented was] neither legitimate, nor public, nor

authentic, nor solemn [...] after analysis by all the judges of

the investigative Council, it proved to be nothing more than a

simple paper.

(CANOVA & MARTUCHO)

What is clear is that a

pretender who did not belong to the Colón family would have to forge

all of his documents to have any chance of entering the inheritance

lawsuit.

And among the papers

presented by Baltazar Colombo is a Last Will of 1498. In it one can

read,

"I was born in

Genoa."

The 1498 Last Will was

suspected at the outset as not authentic, thus fraudulent, and duly

rejected:

And because it was

said, explicitly and openly, that the aforementioned Baltazar

had previously presented the aforementioned Last Will, which he

considers authentic, along with other writings, Your Majesty

should not accept the fraud that may result, because what

Baltazar previously presented was supposed to correspond only to

a missing page of the [true] Last Will of 1502.

(CANOVA & MARTUCHO)

Do The

Forgeries Say It All?

When we saw this 1498 Last Will at the Archivo General de Indias in

Seville in 2003, we knew instantly that it was a forgery.

The first word of the

document reads, "Tresaldo," which means Copy, yet the document is

signed "El Almirante," The Admiral.

Another words, this

supposed copy is signed by the Admiral who was already dead.

Furthermore, the date on the document is 1 598 but someone wrote a 4

over the 5 to make it look like 1498, as shown in Figure 6.

The Last Will of 1498,

claiming Colón was born in Genoa and utilized today by so many

historians in their false claims that Colón was the Genoese Colombo,

was reviewed and rejected as a forgery by the Spanish Tribunal in

the 16th century.

Figure 6.

The

fraudulent 1498 Last Will's first page on the left

has as

its first word Treslado.

The

last page on the right shows the signature

"El

Almirante" instead of a name,

and the

date 1 598 corrected to 1 498,

as seen

on inset.

(Arquivo Geral de Índias, PATRONATO, 295, N.101.)

Only 72 years had passed since the death of the First Admiral of the

Indies.

Still, no person in

Genoa, and not even the Genoese government, seemed to know that the

famous Don Cristóbal Colón was supposed to be the Cristoforo Colombo

weaver from that city.

Genoa's Senate chose

instead to support a false Bernardo Colombo pretender from Cogoleto

to go to Spain and try to steal the inheritance from the navigator's

legitimate descendants.

This episode shows how no one in Genoa believed that Don Cristóbal

Colón was Genoese, despite the publications and searches for

relatives of the navigator carried out by the Senate of Genoa.

The best they could find

were two postulants, Bernardo de Cogoleto and Baltazar de

Cuccaro, both without any blood ties to the famous Spanish

Colón.

Since Don Cristóbal Colón never belonged to a Colombo family and

considering that he was not born in Genoa, as it appears he was not,

all Genoese documents become suspicious of being fraudulent and

should be discarded as not being part of Don Cristóbal Colón's

story.

The puzzle of Don

Cristóbal's identity became much more complicated because of

Baltazar's false documents that historians later accepted as

authentic and continue to be accepted nowadays.

They also claim

falsely that the surnames Colón and Colombo were the same.

Baltazar Colombo

appears as Baltazar Colon in several of the lawsuit documents,

something intolerable to accept because, as we have shown, the

two surnames are very different in meaning, and the two families

were unrelated.

(CANOVA & MARTUCHO)

How was it that the

Tribunal of the Indies rejected the 1498 Last Will as "not

authentic" and this deception by Baltazar came to be accepted as

authentic by historians,

who then presented it

as the only Iberian proof of Colón's Genoese birth?

The Assereto

Document Age Discrepancy

The last document utilized in the fraud of the Genoese Columbus, and

the last one we will discuss here (since they are discussed in

detail in our book) is called the

Assereto Document.

Another fabricated

document supposedly from 1479 claiming that a Cristoforo Colombo

from Genoa was sent to Madeira Island by Paulo Di Negro to buy sugar

without money.

The Assereto describes

Cristoforo Colombo as being 27 years old in 1479.

Even if we choose to ignore all the physical irregularities of the

document that make it suspect, we are left with the following

unlikely scenario.

That Colombo had been

sent by Di Negro to buy sugar at the end of the world, since Madeira

and the Azores, in 1479, were the known end of the European world to

the west; but Di Negro did not give him money to make the purchase!

Would any commercial agent act with such incompetence by sending a

buyer so far to buy sugar without giving him the money?

Perhaps no more evidence is needed than the year of birth to prove

that Colombo was not Colón. Don Cristóbal Colón wrote several times

that he was 28 years old in 1484. Therefore, the navigator was born

in 1455 or 1456.

However, the Colombo from

the Assereto was born in 1451. Unlike words and opinions, the math

does not lie. A person cannot be 27 years old in 1479 and then be 28

years old in 1484.

The only explanation is

that Colón and Colombo were two different people.

Two Very

Different Men

Admiral Colón, not only by his 1479 marriage to a Portuguese high

noble dame, but also in all of his writings, deeds, relations with

the nobility, and connections to the courts, shows himself to be,

a very cultured

person, full of authority, immersed in matters of the sea since

his childhood; a person who studied throughout his youth, who

never worked a day in manual labor, and who, in his own words,

told us he started his seafaring career at a very young age...

Even if we set aside the

fact that the navigator's name was never Colombo and that he was not

a peasant, we can still show that the weaver was not the mariner.

Two of the three

primary documents supporting the weaver theory are

scientifically unacceptable.

There is not a single

piece of documentary evidence today to maintain that the two

men, the weaver and the navigator, were one.

The Last Will of 1498

is a forgery not written by Colón, the Assereto Document

gives that Colombo as born in 1451.

Yet Don Cristóbal

Colón was born in 1455/56, because he wrote several times

that he was 28 years old in 1484 when he entered Spain.

While the weaver

Cristoforo Colombo spent his youth behind a loom in Genoa,

Cristóbal Colón spent his youth in school.

Among the expertise

his studies provided him are the languages of Portuguese,

Castilian, and Latin, in addition to familiarity with Greek and

Hebrew - but did NOT know the Italian language.

(TEXTOS,

215.)

In the sciences he was

acquainted with geography, cosmography, geometry, cartography,

theology, mathematics, advanced navigation techniques, and even

encryption.

We know Bobadilla

confiscated secret encrypted letters that Don Cristóbal wrote to his

brother Don Bartolomé.

Don Bartolomé Colón

himself was not far behind Don Cristóbal because aside from

encryption, he wrote at least Castilian and Latin.

Don Bartolomé was so

well educated in Cartography and Navigation that he equaled his

brother.

In 1493, following

written instructions left by Don Cristóbal, Don Bartolomé

captained a fleet of ships directly to Haiti without ever having

sailed there.

Friar Las Casas

wrote,

"not less educated in

Cosmography and what pertains to it, and in making of, or

painting, of navigation charts and globes and other instruments

of that art, than his brother".

(LAS

CASAS, T. II, 214.)

Like Don Cristóbal, Don

Bartolomé was a man of the sea, and not a wool weaver, to whom Don

Cristóbal entrusted important tasks like the governance of the New

World in his absence or the preparing of the ships, as he declared,

"the Lord Lieutenant

already left with the ships for careening in the old town."

(THACHER,

Vol. 3, 264.)

Occam's logic tells us

that if we are going to doubt any of the documents, we must start by

doubting those which are foreign to the Admiral, written by other

people who lived in another world and, thus, separated from the

events by time and space, before we choose to put in doubt the

documents written by the subject about his own life.

We must not fall into the same mistakes as the past investigators

and discard the words of a noble Admiral and Viceroy to impose facts

that do not fit his life.

We must demand the truth,

by every means possible, and not allow ourselves to accept as truth

documents that are clearly fraudulent, composed of uncertainties,

and not even related to the person whose life we are scrutinizing.

I submit that the Spanish documents are enough proof that Don

Cristóbal Colón was not Cristoforo Colombo, and he

was not a Genoese peasant.

Today, nobody

knows who Don Cristóbal Colón actually was because we

have spent centuries investigating and writing about the wrong guy.

Furthermore, DNA tests

currently underway at the University of Granada will likely fail to

give us a final identity of the famous Admiral because out of all

the candidates being compared by Professor José Lorente,

there is not one who fits the profile of the great navigator.

In our latest book we have presented a mountain of irrefutable

evidence in support of the Polish-Portuguese prince born on Madeira

Island and await access to the bones in Wawel Cathedral for future

DNA testing.

Therefore, this ongoing "

Columbus" Identity Mystery will take a long while yet to solve. We

are only at the beginning of the truth!

For further explanation and full references of supporting evidence,

read

COLUMBUS - The Untold Story.

References

-

ANGHIERA, Pietro

Martire d', De orbe nouo Petri Martyris ab Angleria

Mediolanensis protonotarij C[a]esaris senatoris decades, Logart

Press, 1530, iii, iiii.

-

ANGHIERA, Pietro Martire d', De Orbe Novo, Petri Martyris ab

Angleria Mediolanensis protonotarii cesaris senatoris decades,

Logart Press,1530.

-

BERNÁLDEZ, Andrés, Historia de los reyes católicos Don Fernando

y Doña Isabel, Cap. CXVIII.

-

CANOVA, Scipion e MARTUCHO, Carlos, Por Don Baltasar Colombo,

contra Don Nuño de Portugal, y consortes, sobre el Almirantazgo

de las Indias, Ducado de Veragua, y Marquesado de Iamayca …,

1601.

-

COLÓN, Cristóbal, Relaciones y cartas de Cristóbal Colón,

Librería de La Viuda de Hernando y C.ª, Calle Del Arenal, Núm.

11, Madrid, 1892, 380-381.

-

COLÓN, Cristóbal and VARELA, Consuelo Cristóbal Colón Textos y

documentos completos: relaciones de viajes, cartas y memoriales,,

Alianza Editorial, 1989, 215.

-

COLÓN, Hernando, HISTORIE, Cap. I, 3. Noi vogliamo ridurre alla

pronuncia latina ch'è Chriftophorus Colonus.

-

DORNELAS, Afonso, Elementos para o estudo etimológico do apelido

Colon, Centro Tipográfico Colonial, Lisboa, 1926, 10.

-

EZQUERRA ABADÍA, Ramón. La nacionalidad de Colón: Estado actual

del problema. Sep. de Vol. 4 del XXXVI Congreso Internacional de

Americanistas, Sevilla, 1966, 417.

-

GANDÍA, Enrique de, História de Cristóbal Colón. Análisis

crítico de las fuentes documentales y de los problemas

colombinos, Buenos Aires, 1942, pág. 52.

-

LAS CASAS, Fray Bartolomé de, Historia de las Indias, Imprenta

de Miguel Ginesta, Madrid, 1875

-

MORISON, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Time

Incorporated, New York, 1962, 33. Centurione had given Di Negro

1290 ducats for this purpose, but Di Negro gave Colombo only

103½ ducats.

-

OVIEDO Y VALDÉS, Gonzalo Fernández de, Historia general de las

Indias, 1525, Libro Segundo, iii.

-

POSA, Pedro, Letter of Columbus to Luis de Santangel, 1493. New

York Public Library. Available online:

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7fbc3989-f804-30a9-e040-e00a18067752/book#page/1/mode/2up.

-

Raccolta di documenti e studi pubblicati dalla R. Commissione

colombiana, MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE, Roma,

1892-1896.

-

SANZ, Carlos, La carta de Colon: anunciando el descubrimiento

del Nuevo Mundo 15 Febrero-14 Marzo 1493, Talleres Hauser y

Menet, Madrid, 1956, 23.

-

THACHER, John Boyd, Christopher Columbus: his life, his work,

his remains, as revealed by original printed and manuscript

records, New York and London, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1903-4, Vol.

3, 264.

|