|

by Hattie Greene Lockett

from

Gutemberg Website

|

Produced by David Starner,

Stephanie Maschek and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

Vol. IV, No. 4 May 15, 1933

University of Arizona Bulletin

SOCIAL SCIENCE BULLETIN No. 2

The Unwritten Literature of the Hopi

BY HATTIE GREENE LOCKETT

PUBLISHED BY University of Arizona TUCSON, ARIZONA

The Unwritten Literature of the Hopi[1]

.

[Footnote 1: A

thesis accepted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the Master of Arts degree in

Archaeology, University of Arizona, 1933. Published

under the direction of the Committee on Graduate Study,

R.J. Leonard, Chairman.] |

Contents

-

Introduction

-

The Hopi

-

Hopi Social Organization

-

Pottery And Basket Making

Traditional - Its Symbolism

-

House Building

-

Myth And Folktale - General

Discussion

-

Hopi Religion

-

Ceremonies - General

Discussion

-

Hopi Myths And Traditions And

Some Ceremonies Based Upon Them

-

Ceremonies For Birth,

Marriage, Burial

-

Stories Told Today

-

Conclusion

I.

INTRODUCTION

SHOWING THAT THE PRESENT-DAY

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE HOPI IS THE OUTGROWTH OF THEIR UNWRITTEN

LITERATURE

GENERAL STATEMENT

By a brief survey of present day Hopi culture and an examination

into the myths and traditions constituting the unwritten literature

of this people, this bulletin proposes to show that an intimate

connection exists between their ritual acts, their moral standards,

their social organization, even their practical activities of today,

and their myths and tales—the still unwritten legendary lore.

The myths and legends of primitive peoples have always interested

the painter, the poet, the thinker; and we are coming to realize

more and more that they constitute a treasure-trove for the

archaeologist, and especially the anthropologist, for these sources

tell us of the struggles, the triumphs, the wanderings of a people,

of their aspirations, their ideals and beliefs; in short, they give

us a twilight history of the race.

As the geologist traces in the rocks the clear record of the early

beginnings of life on our planet, those first steps that have led

through the succession of ever-developing forms of animal and plant

life at last culminating in man and the world as we now see them, so

does the anthropologist discover in the myths and legends of a

people the dim traces of their origin and development till these

come out in the stronger light of historical time. And it is at this

point that the ethnologist, trying to understand a race as he finds

them today, must look earnestly back into the “realm of beginnings,”

through this window of so-called legendary lore, in order to account

for much that he finds in the culture of the present day.

The Challenge: Need of Research on

Basic Beliefs Underlying Ceremonies

Wissler says:[2]

“It is still an open question in

primitive social psychology whether we are justified in assuming

that beliefs of a basic character do motivate ceremonies. It

seems to us that such must be the case, because we recognize a

close similarity in numerous practices and because we are

accustomed to believe in the unity of the world and life. So it

may still be our safest procedure to secure better records of

tribal traditional beliefs and to deal with objective procedures

as far as possible. No one has ventured to correlate specific

beliefs and ceremonial procedures, but it is through this

approach that the motivating power of beliefs will be revealed,

if such potency exists.”

[Footnote 2: Wissler, Clark, An

Introduction to Social Anthropology: Henry Holt &Co., New York,

1926, p. 266.]

Some work has been done along this line by Kroeber for the tribes of

California, Lowie for the Crow Indians, and Junod for the Ekoi of

West Africa; but it appears that the anthropological problem of

basic beliefs and philosophies is dependent upon specific tribal

studies and that more research is called for.

The Myth, Its Meaning and Function in Primitive Life

As a background for our discussion we shall need to consider first,

the nature and significance of mythology, since there is some,

indeed much, difference of opinion on the subject, and to arrive at

some basis of understanding as to its function.

The so-called school of Nature-Mythology, which flourishes mainly in

Germany, maintains that primitive man is highly interested in

natural phenomena, and that this interest is essentially of a

theoretic, contemplative and poetical character. To writers of this

school every myth has as its kernel or essence some natural

phenomenon or other, even though such idea is not apparent upon the

surface of the story; a deeper meaning, a symbolic reference, being

insisted upon. Such famous scholars as Ehrenreich, Siecke, Winckler,

Max Muller, and Kuhn have long given us this interpretation of myth.

In strong contrast to this theory which regards myth as

naturalistic, symbolic, and imaginary, we have the theory which

holds a sacred tale as a true historical record of the past. This

idea is supported by the so-called Historical school in Germany and

America, and represented in England by Dr. Rivers. We must admit

that both history and natural environment have left a profound

imprint on all cultural achievement, including mythology, but we are

not justified in regarding all mythology as historical chronicle,

nor yet as the poetical musings of primitive naturalists. The

primitive does indeed put something of historical record and

something of his best interpretation of mysterious natural phenomena

into his legendary lore, but there is something else, we are led to

believe, that takes precedence over all other considerations in the

mind of the primitive (as well as in the minds of all of the rest of

us) and that is getting on in the world, a pragmatic outlook.

It is evident that the primitive relies upon his ancient lore to

help him out in his struggle with his environment, in his needs

spiritual and his needs physical, and this immense service comes

through religious ritual, moral incentive, and sociological pattern,

as laid down in the cherished magical and legendary lore of his

tribe.

The close connection between religion and mythology, under-estimated

by many, has been fully appreciated by the great British

anthropologist, Sir James Frazer, and by classical scholars like

Miss Jane Harrison. The myth is the Bible of the primitive, and just

as our Sacred Story lives in our ritual and in our morality, as it

governs our faith and controls our conduct, even so does the savage

live by his mythology.

The myth, as it actually exists in a primitive community, even

today, is not of the nature of fiction such as our novel, but is a

living reality, believed to have once happened in primeval times

when the world was young and continuing ever since to influence the

world and human destiny.

The mere fireside tale of the primitive may be a narrative, true or

imaginary, or a sort of fairy story, a fable or a parable, intended

mainly for the edification of the young and obviously pointing a

moral or emphasizing some useful truth or precept. And here we do

recognize symbolism, much in the nature of historical record. But

the special class of stories regarded by the primitive as sacred,

his sacred myths, are embodied in ritual, morals, and social

organization, and form an integral and active part of primitive

culture. These relate back to best known precedent, to primeval

reality, by which pattern the affairs of men have ever since been

guided, and which constitute the only “safe path.”

Malinowski[3] stoutly maintains that these stories concerning the

origins of rites and customs are not told in mere explanation of

them; in fact, he insists they are not intended as explanations at

all, but that the myth states a precedent which constitutes an ideal

and a warrant for its continuance, and sometimes furnishes practical

directions for the procedure. He feels that those who consider the

myths of the savage as mere crude stories made up to explain natural

phenomena, or as historical records true or untrue, have made a

mistake in taking these myths out of their life-context and studying

them from what they look like on paper, and not from what they do in

life.

[Footnote 3: Malinowski, B.,

Myth in Primitive Psychology: M.W. Norton & Co., Inc., New York,

1926, p. 19.]

Since Malinowski’s definition of myth differs radically from that of

many other writers on the subject, we would refer the reader to the

discussion of myth under the head of Social Anthropology in the

Encyclopedia Britannica, Fourteenth Edition, page 869.

Back to Contents

II. THE HOPI

Their Country—The People

The Hopi Indians live in northern Arizona about one hundred miles

northeast of Flagstaff, seventy miles north of Winslow, and

seventy-five miles north of Holbrook.

For at least eight hundred years the Hopi pueblos have occupied the

southern points of three fingers of Black Mesa, the outstanding

physical feature of the country, commonly referred to as First,

Second, and Third Mesas.

It is evident that in late prehistoric times several large villages

were located at the foot of First and Second Mesas, but at present,

except for two small settlements around trading posts, the villages

are all on top of the mesas. On the First Mesa we find Walpi,

Sichomovi, and Hano, the latter not Hopi but a Tewa village built

about 1700 by immigrants from the Rio Grande Valley, and at the foot

of this mesa the modern village of Polacca with its government

school and trading post. On Second Mesa are Mashongnovi, Shipaulovi,

and Shungopovi, with Toreva Day School at its foot.

On Third Mesa Oraibi, Hotavilla, and

Bacabi are found, with a government school and a trading post at

Lower Oraibi and another school at Bacabi. Moencopi, an offshoot

from Old Oraibi, is near Tuba City.

This area was once known as the old Spanish Province of Tusayan, and

the Hopi villages are called pueblos, Spanish for towns. In 1882,

2,472,320 acres of land were set aside from the public domain as the

Hopi Indian Reservation. At present the Hopi area is included within

the greater Navajo Reservation and administered by a branch of the

latter Indian agency.

The name Hopi or Hopitah means “peaceful people,” and the name Moqui,

sometimes applied to them by unfriendly Navajo neighbors, is really

a Zuni word meaning “dead,” a term of derision. Naturally the Hopi

do not like being called Moqui, though no open resentment is ever

shown. Early fiction and even some early scientific reports used the

term Moqui instead of Hopi.

Admirers have called these peaceful pueblo dwellers “The Quaker

People,” but that is a misnomer for these sturdy brown heathen who

have never asked or needed either government aid or government

protection, have a creditable record of defensive warfare during

early historic times and running back into their traditional

history, and have also some accounts of civil strife.

The nomadic Utes, Piutes, Apaches, and Navajos for years raided the

fields and flocks of this industrious, prosperous, sedentary people;

in fact, the famous Navajo blanket weavers got the art of weaving

and their first stock of sheep through stealing Hopi women and Hopi

sheep. But there came a time when the peaceful Hopi decided to kill

the Navajos who stole their crops and their girls, and then

conditions improved. Too, soon after, came the United States

government and Kit Carson to discipline the raiding Navajos.

The only semblance of trouble our government has had with the Hopi

grew out of the objection, in fact, refusal, of some of the more

conservative of the village inhabitants to send their children to

school. The children were taken by force, but no blood was shed, and

now government schooling is universally accepted and generally

appreciated.

A forbidding expanse of desert waste lands surrounds the Hopi mesas,

furnishing forage for Hopi sheep and goats during the wet season and

browse enough to sustain them during the balance of the year. These

animals are of a hardy type adapted to their desert environment. Our

pure blood stock would fare badly under such conditions. However,

the type of wool obtained from these native sheep lends itself far

more happily to the weaving of the fine soft blankets so long made

by the Hopi than does the wool of our high grade Merino sheep or a

mixture of the two breeds. This is so because our Merino wool

requires the commercial scouring given it by modern machine methods,

whereas the Hopi wool can be reduced to perfect working condition by

the primitive hand washing of the Hopi women.

As one approaches the dun-colored mesas from a distance he follows

their picturesque outlines against the sky line, rising so abruptly

from the plain below, but not until one is within a couple of miles

can he discern the villages that crown their heights. And no wonder

these dun-colored villages seem so perfectly a part of the mesas

themselves, for they are literally so—their rock walls and dirt

roofs having been merely picked up from the floor and sides of the

mesa itself and made into human habitations.

The Hopi number about 2,500 and are a Shoshonean stock. They speak a

language allied to that of the Utes and more remotely to the

language of the Aztecs in Mexico.[4]

[Footnote 4: Colton, H.S.,

Days in the Painted Desert: Museum Press, Flagstaff, 1932, p. 17.]

According to their traditions the various Hopi clans arrived in

Hopiland at different times and from different directions, but they

were all a kindred people having the same tongue and the same

fundamental traditions.

They did not at first build on the tops of the mesas, but at their

feet, where their corn fields now are, and it was not from fear of

the war-like and aggressive tribes of neighboring Apaches and

Navajos that they later took to the mesas, as we once supposed. A

closer acquaintance with these people brings out the fact that it

was not till the Spaniards had come to them and established Catholic

Missions in the late Seventeenth Century that the Hopi decided to

move to the more easily defended mesa tops for fear of a punitive

expedition from the Spaniards whose priests they had destroyed.

We are told that these desert-dwellers, whose very lives have always

depended upon their little corn fields along the sandy washes that

caught and held summer rains, always challenged new-coming clans to

prove their value as additions to the community, especially as to

their magic for rain-making, for life here was a hardy struggle for

existence, with water as a scarce and precious essential. Among the

first inhabitants was the Snake Clan with its wonderful ceremonies

for rain bringing, as well as other sacred rites. Willingly they

accepted the rituals and various religious ceremonials of new-comers

when they showed their ability to help out with the eternal problem

of propitiating the gods that they conceived to have control over

rain, seed germination, and the fertility and well-being of the

race.

In exactly the same spirit they welcomed the friars. Perhaps these

priests had “good medicine” that would help out. Maybe this new kind

of altar, image, and ceremony would bring rain and corn and health;

they were quite willing to try them. But imagine their consternation

when these Catholic priests after a while, unlike any people who had

ever before been taken into their community, began to insist that

the new religion be the only one, and that all other ceremonies be

stopped. How could the Hopi, who had depended upon their old

ceremonies for centuries, dare to stop them? Their revered

traditions told them of clans that had suffered famine and sickness

and war as punishment for having dropped or even neglected their

religious dances and ceremonies, and of their ultimate salvation

when they returned to their faithful performance.

The Hopi objected to the slavish labor of bringing timbers by hand

from the distant mountains for the building of missions and,

according to Hopi tradition, to the priests taking some of their

daughters as concubines, but the breaking point was the demand of

the friars that all their old religious ceremonies be stopped; this

they dared not do.

So the “long gowns” were thrown over the cliff, and that was that.

Certain dissentions and troubles had come upon them, and some crop

failures, so they attributed their misfortunes to the anger of the

old gods and decided to stamp out this new and dangerous religion.

It had taken a strong hold on one of their villages, Awatobi, even

to the extent of replacing some of the old ceremonies with the new

singing and chanting and praying. And so Awatobi was destroyed by

representatives from all the other villages.

Entering the sleeping village just

before dawn, they pulled up the ladders from the underground kivas

where all the men of the village were known to be sleeping because

of a ceremony in progress, then throwing down burning bundles and

red peppers they suffocated their captives, shooting with bows and

arrows those who tried to climb out. Women and children who resisted

were killed, the rest were divided among the other villages as

prisoners, but virtually adopted. Thus tenaciously have the Hopi

clung to their old religion—noncombatants so long as new cults among

them do not attempt to stop the old.

There are Christian missionaries among them today, notably Baptists,

but they are quite safe, and the Hopi treat them well. Meantime the

old ceremonies are going strong, the rain falls after the Snake

Dance, and the crops grow. The Hopi realize that missionary

influence will eventually take some away from the old beliefs and

practices and that government school education is bound to break

down the old traditional unity of ideas. Naturally their old men are

worried about it.

Yet their faith is strong and their

disposition is kindly and tolerant, much like that of the good old

Methodist fathers who are disturbed over their young people being

led off into new angles of religious belief, yet confident that “the

old time religion” will prevail and hopeful that the young will be

led to see the error of their way. How long the old faith can last,

in the light of all that surrounds it, no one can say, but in all

human probability it is making its last gallant stand.

These Pueblo Indians are very unlike the nomadic tribes around them.

They are a sedentary, peaceful people living in permanent villages

and presenting today a significant transitional phase in the advance

of a people from savagery toward civilization and affording a

valuable study in the science of man.

Naturally they are changing, for easy transportation has brought the

outside world to their once isolated home.

It is therefore highly important that they be studied first-hand now

for they will not long stay as they are.

Back to Contents

III. HOPI

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

Government

In government, the village is the unit, and a genuinely democratic

government it is. There is a house chief, a Kiva chief, a war chief,

the speaker chief or town crier, and the chiefs of the clans who are

likewise chiefs of the fraternities; all these making up a council

which rules the pueblo, the crier publishing its decisions. Laws are

traditional and unwritten. Hough[5] says infractions are so few that

it would be hard to say what the penalties are, probably ridicule

and ostracism. Theft is almost unheard of, and the taking of life by

force or law is unknown.

[Footnote 5: Hough, Walter,

The Hopi: Torch Press, Cedar Rapids, 1915.]

To a visitor encamped at bedtime below the mesa, the experience of

hearing the speaker chief or town crier for the first time is

something long to be remembered. Out of the stillness of the desert

night comes a voice from the house tops, and such a voice! From the

heights above, it resounds in a sonorous long-drawn chant. Everyone

listens breathlessly to the important message and it goes on and on.

The writer recalls that when first she heard it, twenty years ago,

she sat up in bed and rousing the camp, with stage whispers (afraid

to speak aloud), demanded: “Do you hear that? What on earth can it

mean? Surely something awful has happened!” On and on it went

endlessly. (She has since been told that it is all repeated three

times.) And not until morning was it learned that the long speech

had been merely the announcement of a rabbit hunt for the next day.

The oldest traditions of the Hopi tell of this speaker chief and his

important utterances. He is a vocal bulletin board and the local

newspaper, but his news is principally of a religious nature, such

as the announcement of ceremonials. This usually occurs in the

evening when all have gotten in from the fields or home from the

day’s journey, but occasionally announcements are made at other

hours.

The following is a poetic formal announcement of the New Fire

Ceremony, as given at sunrise from the housetop of the Crier at

Walpi:

“All people awake, open your

eyes, arise,

Become children of light, vigorous, active, sprightly:

Hasten, Clouds, from the four world-quarters.

Come, Snow, in plenty, that water may abound when summer

appears.

Come, Ice, and cover the fields, that after planting

they may yield

abundantly.

Let all hearts be glad.

The Wuwutchimtu will assemble in four days;

They will encircle the villages, dancing and singing.

Let the women be ready to pour water upon them

That moisture may come in plenty and all shall

rejoice.”[6]

[Footnote 6: Hough, Walter, Op. cit.,

p. 43.]

As to the character of their government, Hewett says:[7]

“We can truthfully say that these

surviving pueblo communities constitute the oldest existing

republics. It must be remembered, however, that they were only

vest-pocket editions. No two villages nor group of villages ever

came under a common authority or formed a state. There is not

the faintest tradition of a ‘ruler’ over the whole body of the

Pueblos, nor an organization of the people of this vast

territory under a common government.”

[Footnote 7: Hewett, E.L., Ancient

Life in the American Southwest: Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis,

1929, p. 71.]

The Clan and Marriage

Making up the village are various clans. A clan comprises all the

descendants of a traditional maternal ancestor. Children belong to

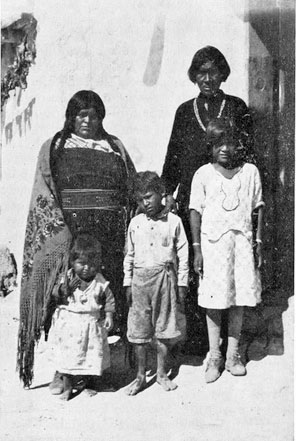

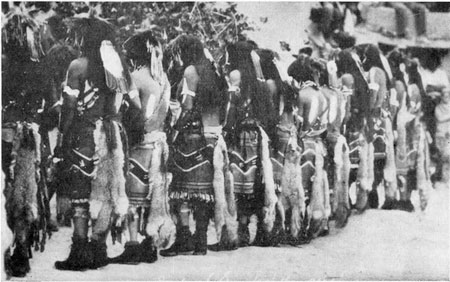

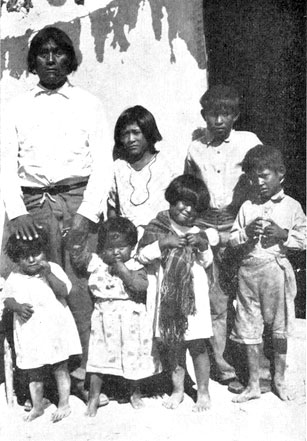

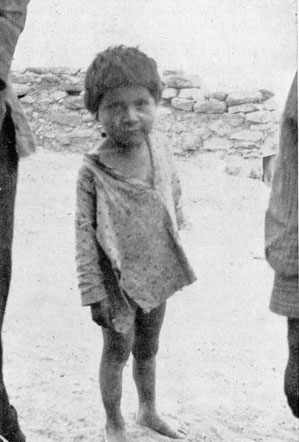

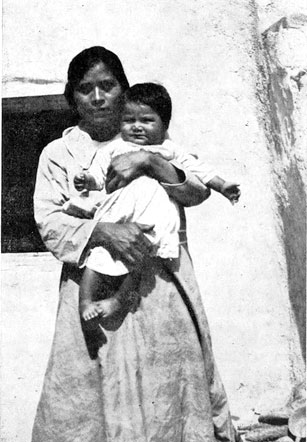

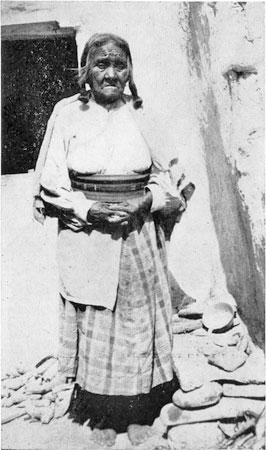

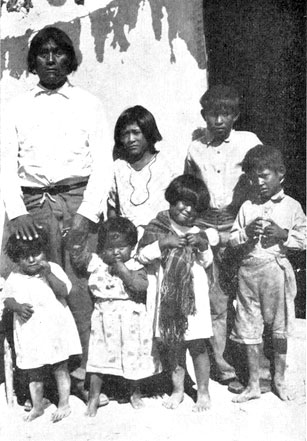

the clan of the mother. (See Figure 1.) These clans bear the name of

something in nature, often suggested by either a simple or a

significant incident in the legendary history of the people during

migration when off-shoots from older clans were formed into new

clans. Thus a migration legend collected by Voth[8] accounts for the

name of the Bear Clan, the Bluebird Clan, the Spider Clan, and

others.

[Footnote 8: Voth, H.R.,

Traditions of the Hopi: Field Columbian Museum Pub. 96,

Anthropological series, vol. 8, pp. 36-38, 1905.]

Sons and daughters are expected to marry outside the clan, and the

son must live with his wife’s people, so does nothing to perpetuate

his own clan. The Hopi is monogamous. A daughter on marrying brings

her husband to her home, later building the new home adjacent to

that of her mother. Therefore many daughters born to a clan mean

increase in population.

Figure 1.—Hopi Family

at Shungopovi.—Photo by Lockett

Some clans have indeed become nearly

extinct because of the lack of daughters, the sons having naturally

gone to live with neighboring clans, or in some cases with

neighboring tribes. As a result, some large houses are pointed out

that have many unoccupied and even abandoned rooms—the clan is dying

out. Possibly there may be a good many men of that clan living but

they are not with or near their parents and grandparents. They are

now a part of the clan into which they have married, and must live

there, be it near or far. Why should they keep up such a practice

when possibly the young man could do better, economically and

otherwise, in his ancestral home and community?

The answer is, “It has always been that

way,” and that seems to be reason enough for a Hopi.

Property, Lands, Houses, Divorce

Land is really communal, apportioned to the several clans and by

them apportioned to the various families, who enjoy its use and hand

down such use to the daughters, while the son must look to his

wife’s share of her clan allotment for his future estate. In fact,

it is a little doubtful whether he has any estate save his boots and

saddle and whatever personal plunder he may accumulate, for the

house is the property of the wife, as well as the crop after its

harvest, and divorce at the pleasure of the wife is effective and

absolute by the mere means of placing said boots and saddle, etc.,

outside the door and closing it. The husband may return to his

mother’s house, and if he insists upon staying, the village council

will insist upon his departure.

Again, why do they keep doing it this way? Again, “Because it has

always been done this way.” And it works very well. There is little

divorce and little dissension in domestic life among the Hopi, in

spite of Crane’s[9] half comical sympathy for men in this

“woman-run” commonwealth. Bachelors are rare since only heads of

families count in the body politic. An unmarried woman of

marriageable age is unheard of.

[Footnote 9: Crane, Leo,

Indians of the Enchanted Mesa: Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1925.]

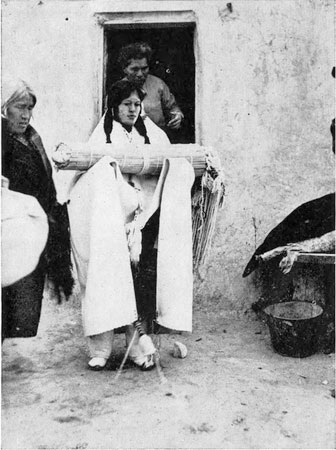

Woman’s Work

The Hopi woman’s life is a busy one, the never finished grinding of

corn by the use of the primitive metate and mano taking much time,

and the universal woman’s task of bearing and rearing children and

providing meals and home comforts accounting for most of her day.

She is the carrier of water, and since it must be borne on her back

from the spring below the village mesa this is a burden indeed. She

is, too, the builder of the house, though men willingly assist in

any heavy labor when wanted. But why on earth should so kindly a

people make woman the carrier of water and the mason of her home

walls? Tradition! “It has always been this way.”

Her leisure is employed in visiting her neighbors, for the Hopi are

a conspicuously sociable people, and in the making of baskets or

pottery. One hears a great deal about Hopi pottery, but the pottery

center in Hopiland is the village of Hano, on First Mesa, and the

people are not Hopi but Tewas, whose origin shall presently be

explained.

Not until recent years has pottery been made elsewhere in Hopiland

than at Hano. At present, however, Sichomovi, the Hopi village built

so close to Hano that one scarce knows where one ends and the other

begins, makes excellent pottery as does the Hopi settlement at the

foot of the hill, Polacca. Undoubtedly this comes from the Tewa

influence and in some cases from actual Tewa families who have come

to live in the new locality.

For instance, Grace, maker of excellent

pottery, now living at Polacca, is a Tewa who lived in Hano twenty

years ago, when the writer first knew her, and continued to live

there until a couple of years ago. Nampeo, most famous potter in

Hopiland, is an aged Tewa woman still living at Hano, in the first

house at the head of the trail. Her ambitious study of the fragments

of the pottery of the ancients, in the ruins of old Sikyatki, made

her the master craftsman and developed a new standard for

pottery-making in her little world.

Mention was made previously of the women employing their leisure in

the making of baskets or pottery. An interesting emphasis should be

placed upon the “or,” for no village does both. The women of the

three villages mentioned at First Mesa as pottery villages make no

baskets. The three villages on Second Mesa make a particular kind of

coiled basket found nowhere else save in North Africa, and no

pottery nor any other kind of basket. The villages of Third Mesa

make colorful twined or wicker baskets and plaques, just the one

kind and no pottery. They stick as closely to these lines as though

their wares were protected by some tribal “patent right.” Pottery

for First Mesa, coiled baskets for Second Mesa, and wicker baskets

for Third Mesa.

The writer has known the Hopi a long time, and has asked them many

times the reason for this. The villages are only a few miles apart,

so the same raw materials are available to all. These friends merely

laugh good naturedly and answer: “O, the only reason is, that it is

just the way we have always done it.”

Natural conservatives, these Hopi, and yet not one of them but likes

a bright new sauce-pan from the store for her cooking, and a good

iron stove, for that matter, if she can afford it.

There is no tradition against this, we

are told.

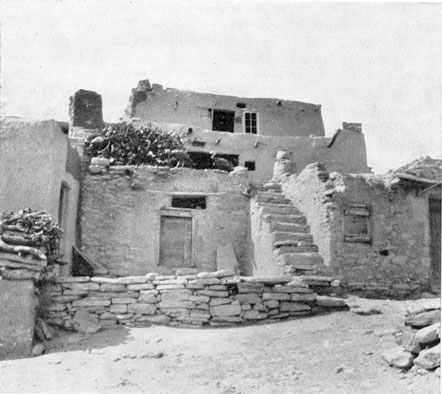

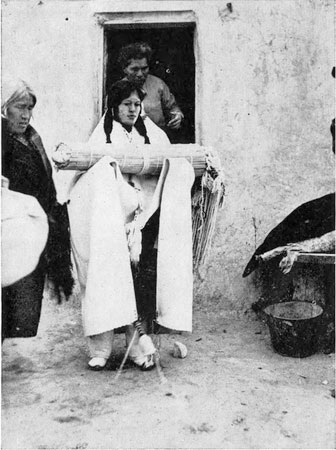

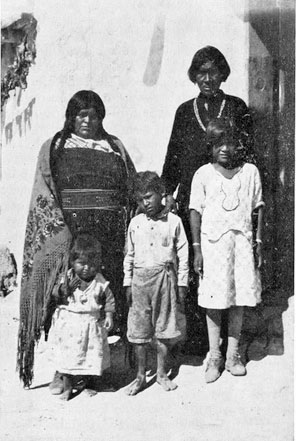

Figure 2.—Walpi.—Photo

by Bortell

More than two centuries ago, these Tewas

came from the Rio Grande region, by invitation of the Walpi, to help

them defend this village (See Figure 2) from their Navajo, Apache,

and Piute enemies. They were given a place on the mesa-top to build

their village, at the head of the main trail, which it was their

business to guard, and fields were allotted them in the valley

below.

They are a superior people, intelligent, friendly, reliable, and so

closely resemble the Hopi that they can not be told apart.

The two peoples have intermarried freely, and it is hard to think of

the Tewas otherwise than as “one kind of Hopi.” However, they are of

a distinctly different linguistic stock, speaking a Tewa language

brought from the Rio Grande, while the Hopi speak a dialect of the

Shoshonean.

It is an interesting fact that all Tewas speak Hopi as well as Tewa,

whereas the Hopi have never learned the Tewa language. The Hopi have

a legend accounting for this:

“When the Hano first came, the Walpi

said to them, ‘Let us spit in your mouths and you will learn our

tongue,’ and to this the Hano consented. When the Hano came up

and built on the mesa, they said to the Walpi, ‘Let us spit in

your mouths and you will learn our tongue,’ but the Walpi would

not listen to this, saying it would make them vomit. This is the

reason why all the Hano can speak Hopi, and none of the Hopi can

talk Hano.”[10]

[Footnote 10: Mindeleff, Cosmos,

Traditional History of Tusayan (After A.M. Stephen): Bureau American

Ethnology, vol. 8, p. 36, 1887.]

Man’s Work

The work of the men must now be accounted for lest the impression be

gained that the industry of the women leaves the males idle and

carefree.

It is but fair to the men to say that first of all they carry the

community government on their shoulders, and the still more weighty

affairs of religion. They are depended upon to keep the seasonal and

other ceremonies going throughout the year, and the Hopi ceremonial

calendar has its major event for each of the twelve months, for all

of which elaborate preparation must be made, including the

manufacture and repair of costumes and other paraphernalia and much

practicing and rehearsing in the kivas.

Someone has said much of the Hopi man’s

time is taken up with “getting ready for dances, having dances, and

getting over dances.” Yes, a big waste of time surely to you and me,

but to the Hopi community—men, women, and children alike—absolutely

essential to their well-being. There could be no health, happiness,

prosperity, not even an assurance of crops without these ceremonies.

The Hopi is a good dry farmer on a small scale, and farming is a

laborious business in the shifting sands of Hopiland. Their corn is

their literal bread of life and they usually keep one year’s crop

stored. These people have known utter famine and even starvation in

the long ago, and their traditions have made them wise. The man

tends the fields and flocks, makes mocassins, does the weaving of

the community (mostly ceremonial garments) and usually brings in the

wood for fuel, since it is far to seek in this land of scant

vegetation, in fact literally miles away and getting farther every

year, so that the man with team and wagon is fortunate indeed and

the rest must pack their wood on burros.

Both men and women gather backloads of

faggots wherever such can be found in walking distance, and said

distance is no mean measure, for these hardy little people have

always been great walkers and great runners.

Hough says:[11]

“Seemingly the men work harder

making paraphernalia and costumes for the ceremonies than at

anything else, but it should be remembered that in ancient days

everything depended, in Hopi belief, on propitiating the

deities. Still if we would pick the threads of religion from the

warp and woof of Hopi life there apparently would not be much

left. It must be recorded in the interests of truth, that Hopi

men will work at days labor and give satisfaction except when a

ceremony is about to take place at the pueblo, and duty to their

religion interferes with steady employment much as fiestas do in

the easy-going countries to the southward. Really the Hopi

deserve great credit for their industry, frugality, and

provident habits, and one must commend them because they do not

shun work and because in fairness both men and women share in

the labor for the common good.”

[Footnote 11: Hough, Walter, Op. cit,

pp. 156-58.]

Back to Contents

IV. POTTERY

AND BASKET MAKING TRADITIONAL; ITS SYMBOLISM

The art of pottery-making is a traditional one; mothers teach their

daughters, even as their mothers taught them. There are no recipes

for exact proportions and mixtures, no thermometer for controlling

temperatures, no stencil or pattern set down upon paper for laying

out the designs. The perfection of the finished work depends upon

the potter’s sense of rightness and the skill developed by

practicing the methods of her ancestors with such variation as her

own originality and ingenuity may suggest.

All the women of a pueblo community know how to make cooking

vessels, at least, and in spare time they gather and prepare their

raw materials, just as the Navajo woman has usually a blanket

underway or the Apache a basket started. The same is true of Hopi

basketry; its methods, designs, and symbolism are all a matter of

memory and tradition.

From those who know most of Indian sacred and decorative symbols, we

learn that two main ideas are outstanding: desire for rain and

belief in the unity of all life. Charms or prayers against drought

take the form of clouds, lightning, rain, etc., and those for

fertility are expressed by leaves, flowers, seed pods, while

fantastic birds and feathers accompany these to carry the prayers.

It may be admitted that the modern craftsman is often enough

ignorant of the full early significance of the motifs used, but she

goes on using them because they express her idea of beauty and

because she knows that always they have been used to express belief

in an animate universe and with the hope of influencing the unseen

powers by such recognition in art.

The modern craftsman may even tell you that the once meaningful

symbols mean nothing now, and this may be true, but the medicine men

and the old people still hold the traditional symbols sacred, and

this reply may be the only short and polite way of evading the

troublesome stranger to whom any real explanation would be difficult

and who would quite likely run away in the middle of the patient

explanation to look at something else. Only those whose friendship

and understanding have been tested will be likely to be told of that

which is sacred lore.

However, if the tourist insists upon

having a story with his basket or pottery and the seller realizes

that it’s a story or no sale, he will glibly supply a story, be he

Indian or white, both story and basket being made for tourist

consumption.

To the old time Indian everything had a being or spirit of its own,

and there was an actual feeling of sympathy for the basket or pot

that passed into the hands of unsympathetic foreigners, especially

if the object were ceremonial. The old pottery maker never speaks in

a loud tone while firing her ware and often sings softly for fear

the new being or spirit of the pot will become agitated and break

the pot in trying to escape. Nampeo, the venerable Tewa potter, is

said to talk to the spirits of her pots while firing them, adjuring

them to be docile and not break her handiwork by trying to escape.

But making things to sell is different—how could it be otherwise?

In one generation Indian craftsmen have come to be of two classes,

those who make quantities of stuff for sale and those few who become

real artists, ambitious to save from oblivion the significance and

idealism of the old art that was done for the glory of the gods.

Indian art may survive with proper encouragement, but it must come

now; after a while will be too late.

A notably fine example of such encouragement is the work of Mary

Russell F. Colton of Flagstaff, Arizona, in the Hopi Craftsman

Exhibition held annually at the Northern Arizona Museum of which she

is art curator. At the 1931 Exhibition, 142 native Hopi sent in 390

objects. Over $1500 worth of material was sold and $200 awarded in

prizes. The attendance total of visitors was 1,642. From this

exhibit a representative collection of Hopi Art was assembled for

the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts at the Grand Central Galleries,

New York City, in December of the same year.

A gratifying feature of these annual

exhibits is the fact that groups of Hopi come in from their

reservation 100 miles away and modestly but happily move about

examining and enjoying these lovely samples of their own best work

and that of their neighbors; and they are quick to observe that it

is the really excellent work that gets the blue ribbon, the cash

prize, and the best sale.

Dr. Fewkes points out that while men invented and passed on the

mythology of the tribe, women wrote it down in symbols on their

handicrafts which became the traditional heritage of all.

The sand paintings made for special ceremonies on the floors of the

various kivas, in front of the altars, are likewise designs carried

only in the memory of the officiating priest and derived from the

clan traditions. All masks and ceremonial costumes are strictly

prescribed by tradition. The corn symbol is used on everything.

Corn has always been the bread of life

to the Hopi, but it has been more than food, it has been bound up by

symbolism with his ideas of all fertility and beneficence. Hopi

myths and rituals recognize the dependence of their whole culture on

corn. They speak of corn as their mother. The chief of a religious

fraternity cherishes as his symbol of high authority an ear of corn

in appropriate wrappings said to have belonged to the society when

it emerged from the underworld.

The baby, when twenty days old, is

dedicated to the sun and has an ear of corn tied to its breast.

Back to Contents

V. HOUSE

BUILDING

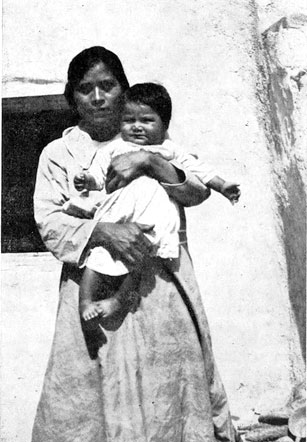

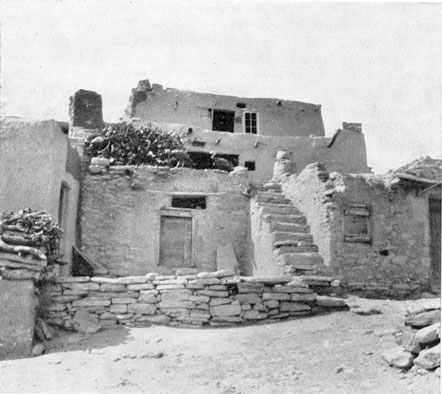

As already stated, the house (See Figure 3) belongs to the woman.

She literally builds it, and she is the head of the family, but the

men help with the lifting of timbers, and now-a-days often lay up

the masonry if desired; the woman is still the plasterer. The

ancestral home is very dear to the Hopi heart, men, women, and

children alike.

After the stone for building has been gathered, the builder goes to

the chief of the village who gives him four small eagle feathers to

which are tied short cotton strings. These, sprinkled with sacred

meal, are placed under the four corner stones of the new house. The

Hopi call these feathers Nakiva Kwoci, meaning a breath prayer, and

the ceremony is addressed to Masauwu. Next, the door is located by

placing a bowl of food on each side of where it is to be. Likewise

particles of food, mixed with salt, are sprinkled along the lines

upon which the walls are to stand.

The women bring water, clay, and earth,

and mix a mud mortar, which is used sparingly between the layers of

stone. Walls are from eight to eighteen inches thick and seven or

eight feet high, above which rafters or poles are placed and smaller

poles crosswise above these, then willows or reeds closely laid, and

above all reeds or grass holding a spread of mud plaster. When

thoroughly dry, a layer of earth is added and carefully packed down.

All this is done by the women, as well as the plastering of the

inside walls and the making of the plaster floors.

Now the owner prepares four more eagle feathers and ties them to a

little willow stick whose end is inserted in one of the central roof

beams. No home is complete without this, for it is the soul of the

house and the sign of its dedication. These feathers are renewed

every year at the feast of Soyaluna.

The writer remembers once seeing a tourist reach up and pull off the

little tuft of breath feathers from the mid-rafter of the little

house he had rented for the night. Naturally he replaced it when the

enormity of his act was explained to him.

Not until the breath feathers have been put up, together with

particles of food placed in the rafters as an offering to Masauwu,

with due prayers for the peace and prosperity of the new habitation,

may the women proceed to plaster the interior, to which, when it is

dry, a coat of white gypsum is applied (all with strokes of the bare

hands), giving the room a clean, fresh appearance.

In one corner of the room is built a

fireplace and chimney, the latter often extended above the roof by

piling bottomless jars one upon the other, a quaint touch, reminding

one of the picturesque chimney pots of England.

Figure 3.—Typical

Hopi Home.—Courtesy Arizona State Museum

The roofs are finished flat and lived

upon as in Mediterranean countries, particularly in the case of

one-story structures built against two-story buildings, the roof of

the low building making the porch or roof-garden for the

second-story room lying immediately adjacent. Here, on the roof many

household occupations go on, including often summer sleeping and

cooking.

When the new house is completely finished and dedicated, the owner

gives a feast for all members of her clan who have helped in the

house-raising, and the guests come bearing small gifts for the home.

Formerly, the house was practically bare of furniture save for the

fireplace and an occasional stool, but the majority of the Hopi have

taken kindly to small iron cook stoves, simple tables and chairs,

and some of them have iron bedsteads. Even now, however, there are

many homes, perhaps they are still in the majority, where the family

sits in the middle of the floor and eats from a common bowl and pile

of piki (their native wafer corn bread), and sleeps on a pile of

comfortable sheep skins with the addition of a few pieces of store

bedding, all of which is rolled up against the wall to be out of the

way when not in use.

In the granary, which is usually a low back room, the ears of corn

are often sorted by color and laid up in neat piles, red, yellow,

white, blue, black, and mottled, a Hopi study in corn color. Strings

of native peppers add to the colorful ensemble.

Back to Contents

VI. MYTH AND

FOLKTALE - GENERAL DISCUSSION

Stability

Because none of this material could be written down but was passed

by word of mouth from generation to generation, changes naturally

occurred. Often a tale traveled from one tribe to another and was

incorporated, in whole or in part, into the tribal lore of the

neighbor—thus adding something. And, we may suppose, some were more

or less forgotten and thus lost; but, as Wissler[12] tells us,

“tales that are directly associated

with ceremonies and, especially, if they must be recited as a

part of the procedure, are assured a long life.”

[Footnote 12: Wissler, Clark, Op.

cit, p. 254.]

Such of these tales as were considered sacred or accounted for the

origin of the people, were held in such high regard as to lay an

obligation upon the tribe to see to it that a number of individuals

learned and retained these texts, perhaps never in fixed wording,

except for songs, but as to essential details of plot.

Many collectors have recorded several versions of certain tales,

thus giving an idea of the range of individual variation, and the

writer herself has encountered as many as three variants for some of

her stories, coming always from the narrators of different villages.

But Wissler,[13] while allowing for

these variations, says:

“All this suggests instability in

primitive mythology. Yet from American data, noting such myths

as are found among the successive tribes of larger areas, it

appears that detailed plots of myths may be remarkably stable.”

[Footnote 13: Wissler, Clark, Op.

cit., p. 254.]

Intrusion of Contemporary Material

However there is another point discussed by Wissler which troubled

the writer greatly as a beginner, and that was the intrusion of new

material with old, for instance, finding an old Hopi story of how

different languages came to exist in the world and providing a

language for the Mamona, meaning the Mormons, who lived among the

Hopi some years ago.

The writer was inclined to throw out the

story, regarding the whole thing as a modern concoction, but

Wissler[14] warns us that:

“From a chronological point of view

we may expect survival material in a tribal mythology along with

much that is relatively recent in origin. It is, however,

difficult to be sure of what is ancient and what recent, because

only the plot is preserved; rarely do we find mention of objects

and environments different from those of the immediate present.”

[Footnote 14: Wissler, Clark, Op.

cit, p. 255.]

A tale, to be generally understood, must often be given a

contemporary setting, and this the narrator instinctively knows,

therefore the introduction of modern material with that of undoubted

age.

Stability, then, lies in the plot rather than in the culture

setting; the former may be ancient, while the latter sometimes

reflects contemporary life.

Boaz[15] argues that much may be learned of contemporary tribal

culture by a study of the mythology of a given people, since so much

of the setting of the ancient tale reflects the tribal life of the

time of the recording. He has made a test of the idea in his study

of the Tsimshian Indians.

From this collection of 104 tales he

concludes that:

“In the tales of a people those

incidents of the everyday life that are of importance to them

will appear either incidentally or as the basis of a plot. Most

of the reference to the mode of life of the people will be an

accurate reflection of their habits. The development of the plot

of the story, further-more, will on the whole exhibit clearly

what is considered right and what wrong.”

[Footnote 15: Boaz, Franz, Tsimshian

Mythology: Bureau American Ethnology, vol. 35, 1916, p. 393.]

How and Why Myths Are Kept

There are set times and seasons for story-telling among the various

Indian tribes, but the winter season, when there is likely to be

most leisure and most need of fireside entertainment, is a general

favorite. However, some tribes have myths that “can not be told in

summer, others only at night, etc.”[16] Furthermore there are secret

cults and ceremonials rigidly excluding women and children, whose

basic myths are naturally restricted in their circulation, but in

the main the body of tribal myth is for the pleasure and profit of

all.

[Footnote 16: Wissler, Clark,

Op. cit., p. 256.]

Old people relate the stories to the children, not only because they

enjoy telling them and the children like listening to them, but

because of the feeling that every member of the tribe should know

them as a part of his education.

While all adults are supposed to know something of the tribal

stories, not all are expected to be good story-tellers.

Story-telling is a gift, we know, and primitives know this too, so

that everywhere we have pointed out a few individuals who are the

best story-tellers, usually an old man, sometimes an old woman, and

occasionally, as the writer has seen it, a young man of some

dramatic ability.

When an important story furnishing a

religious or social precedent is called for, either in council

meeting or ceremonial, the custodian of the stories is in demand,

and is much looked up to; yet primitives rarely create an office or

station for the narrator, nor is the distinction so marked as the

profession of the medicine man and the priest.

Service of Myth

As to the service of myth in primitive life, Wissler[17] says:

“It serves as a body of information,

as stylistic pattern, as inspiration, as ethical precepts, and

finally as art. It furnishes the ever ready allusions to

embellish the oration as well as to enliven the conversation of

the fireside. Mythology, in the sense in which we have used the

term, is the carrier and preserver of the most immaterial part

of tribal culture.”

[Footnote 17: Wissler, Clark, Op.

cit., p. 258.]

Hopi Story-Telling

There comes a time in the Hopi year when crops have been harvested,

most of the heavier and more essentially important religious

ceremonials have been performed in their calendar places, and even

the main supply of wood for winter fires has been gathered. To be

sure, minor dances, some religious and some social, will be taking

place from time to time, but now there will be more leisure, leisure

for sociability and for story-telling.

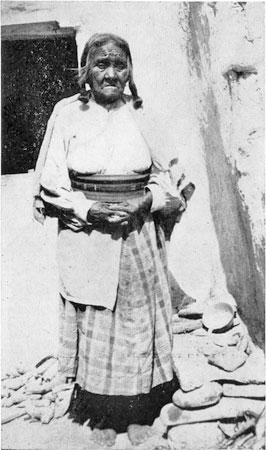

Figure 4.—Kiva at Old

Oraibi.—Courtesy Arizona State Museum

In the kivas (See Figure 4) the priests

and old men will instruct the boys in the tribal legends, both

historical and mythological, and in the religious ceremonies in

which they are all later supposed to participate. In the home, some

good old story-telling neighbor drops in for supper, and stories are

told for the enjoyment of all present, including the children; all

kinds of stories, myths, tales of adventure, romances, and even

bed-time stories. Indian dolls of painted wood and feathers, made in

the image of the Kachinas, are given the children, who thus get a

graphic idea of the supposed appearance of the heroes of some of

these stories.

The Hopi, like many primitive people, believe that when a bird sings

he is weaving a magic spell, and so they have songs for special

magic too; some for grinding, for weaving, for planting, others for

hunting, and still others for war; all definitely to gain the favor

of the gods in these particular occupations.

Without books and without writing the Hopi have an extensive

literature. That a surprising degree of accuracy is observed in its

oral transmission from generation to generation is revealed by

certain comparisons with the records made by the Spanish explorers

in the sixteenth century.

Back to Contents

VII. HOPI

RELIGION

Gods and Kachinas

The Hopi live, move, and have their being in religion. To them the

unseen world is peopled with a host of beings, good and bad, and

everything in nature has its being or spirit.

Just what kind of religion shall we call this of the Hopi? Seeing

the importance of the sun in their rites, one is inclined to say Sun

Worship; but clouds, rain, springs, streams enter into the idea, and

we say Nature Worship. A study of the great Snake Cult suggests

Snake Worship; but their reverence for and communion with the

spirits of ancestors gives to this complex religious fabric of the

Hopi a strong quality of Ancestor Worship. It is all this and more.

The surface of the earth is ruled by a mighty being whose sway

extends to the underworld and over death, fire, and the fields. This

is Masauwu, to whom many prayers are said. Then there is the Spider

Woman or Earth Goddess, Spouse of the Sun and Mother of the Twin War

Gods, prominent in all Hopi mythology. Apart from these and the

deified powers of nature, there is another revered group, the

Kachinas, spirits of ancestors and some other beings, with powers

good and bad. These Kachinas are colorfully represented in the

painted and befeathered dolls, in masks and ceremonies, and in the

main are considered beneficent and are accordingly popular. They

intercede with the spirits of the other world in behalf of their

Hopi earth-relatives.

Masked individuals represent their return to the land of the living

from time to time in Kachina dances, beginning with the Soyaluna

ceremony in December and ending with the Niman or Kachina Farewell

ceremony in July.

Much of this sort of thing takes on a lighter, theatrical flavor

amounting to a pageant of great fun and frolic. Dr. Hough says these

are really the most characteristic ceremonies of the pueblos,

musical, spectacular, delightfully entertaining, and they show the

cheerful Hopi at his best—a true, spontaneous child of nature.

There are a great many of these Kachina dances through the winter

and spring, their nature partly religious, partly social, for with

the Hopi, religion and drama go hand in hand. Dr. Hough speaks

appreciatively of these numerous occasions of wholesome

merry-making, and says these things keep the Hopi out of mischief

and give them a reputation for minding their own business, besides

furnishing them with the best round of free theatrical

entertainments enjoyed by any people in the world. Since every

ceremony has its particular costumes, rituals, songs, there is

plenty of variety in these matters and more detail of meaning than

any outsider has ever fathomed.

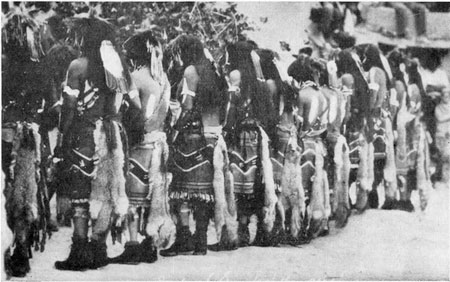

The Niman, or farewell dance of the Kachinas, takes place in July.

It is one of their big nine-day festivals, including secret rites in

the kivas and a public dance at its close.

Messengers are sent on long journeys for sacred water, pine boughs,

and other special objects for these rites.

This is a home-coming festival and a Hopi will make every effort to

get home to his own town for this event. On the ninth day there is a

lovely pageant just before sunrise and another in the afternoon. No

other ceremony shows such a gorgeous array of colorful masks and

costumes. And it is a particularly happy day for the young folk, for

the Kachinas bring great loads of corn, beans, and melons, and

baskets of peaches, especially as gifts for the children; also new

dolls and brightly painted bows and arrows are given them. The

closing act of the drama is a grand procession carrying sacred

offerings to a shrine outside the village.

This is the dance at which the brides of the year make their first

public appearance; their snowy wedding blankets add a lovely touch

to the colorful scene.

Religion Not For Morality

The Hopi is religious, and he is moral, but there is no logical

connection between the two.

Mrs. Coolidge says:[18]

“In all that has been said

concerning the gods and the Kachinas, the spiritual unity of all

animate life, the personification of nature and the correct

conduct for attaining favor with the gods, no reference has been

made to morality as their object. The purpose of religion in the

mind of the Indian is to gain the favorable, or to ward off

evil, influences which the super-spirits are capable of bringing

to the tribe or the individual. Goodness, unselfishness,

truth-telling, respect for property, family, and filial duty,

are cumulative by-products of communal living, closely connected

with religious beliefs and conduct, but not their object. The

Indian, like other people, has found by experience that honesty

is the best policy among friends and neighbors, but not

necessarily so among enemies; that village life is only

tolerable on terms of mutual safety of property and person; that

industry and devotion to the family interest make for prosperity

and happiness. Moral principles are with him the incidental

product of his ancestral experience, not primarily inculcated by

the teaching of any priest or shaman. Yet the Pueblos show a

great advance over many primitive tribes in that their legends

and their priests reiterate constantly the idea that ‘prayer is

not effective except the heart be good.’”

[Footnote 18: Coolidge, Mary Roberts,

The Rain-makers: Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, 1929, p. 203.]

Back to Contents

VIII.

CEREMONIES - GENERAL DISCUSSION

Beliefs and Ceremonials

The beliefs of a tribe, philosophical, religious, and magical, are,

for the most part, expressed in objective ceremonies. The formal

procedure or ritual is essentially a representation or dramatization

of the main idea, usually based upon a narrative. Often the ceremony

opens with or is preceded by the narration of the myth on which it

is based, or the leader may merely refer to it on the assumption

that everyone present knows it.

As to the purpose of the ceremony, there are those who maintain that

entertainment is the main incentive, but the celebration or holiday

seems to be a secondary consideration according to the explanation

of the primitives themselves.

If there chances to be a so-called educated native present to answer

your inquiry on the point, he will perhaps patiently explain to you

that just as July Fourth is celebrated for something more than

parades and firecrackers, and Thanksgiving was instituted for other

considerations than the eating of turkey, so the Hopi Snake Dance,

for instance, is given not so much to entertain the throng of

attentive and respectful Hopi, and the much larger throng of more or

less attentive and more or less respectful white visitors, as to

perpetuate, according to their traditions, certain symbolic rites in

whose efficacy they have profoundly believed for centuries and do

still believe.

Concerning the Pueblos (which include the Hopi), Hewett says:[19]

“There can be no understanding of

their lives apart from their religious beliefs and practices.

The same may be said of their social structure and of their

industries. Planting, cultivating, harvesting, hunting, even

war, are dominated by religious rites. The social order of the

people is established and maintained by way of tribal

ceremonials. Through age-old ritual and dramatic celebration,

practiced with unvarying regularity, participated in by all,

keeping time to the days, seasons and ages, moving in rhythmic

procession with life and all natural forces, the people are kept

in a state of orderly composure and like-mindedness.

“The religious life of the Pueblo Indian is expressed mainly

through the community dances, and in these ceremonies are the

very foundations of the ancient wisdom....”

[Footnote 19: Hewett, E.L., Op. cit.,

p. 117.]

Dance is perhaps hardly the right word

for these ceremonies, yet it is what the Hopi himself calls them,

and he is right. But we who have used the word to designate the

social dances of modern society or the aesthetic and interpretive

dances for entertainment and aesthetic enjoyment will have to tune

our sense to a different key to be in harmony with the Hopi dance.

Our primitive’s communion with nature and with his own spirit have

brought him to a reverent attitude concerning the wisdom of birds,

beasts, trees, clouds, sunlight, and starlight, and most of all he

clings trustingly to the wisdom of his fathers.

“All this,” according to Hewett, “is

voiced in his prayers and dramatized in his dances—rhythm of

movement and of color summoned to express in utmost brilliancy

the vibrant faith of a people in the deific order of the world

and in the way the ancients devised for keeping man in harmony

with his universe. All his arts, therefore, are rooted in

ancestral beliefs and in archaic esthetic forms.”

Surely no people on earth, not even the

Chinese, show a more consistent reverence for the wisdom of the past

as preserved in their myths and legends, than do the Hopi.

Back to Contents

IX. HOPI MYTHS

AND TRADITIONS AND SOME CEREMONIES BASED UPON THEM

The Emergence Myth and the Wu-wu-che-ma

Ceremony

Each of the Hopi clans preserves a separate origin or emergence

myth, agreeing in all essential parts, but carrying in its details

special reference to its own clan. All of them claim, however, a

common origin in the interior of the earth, and although the place

of emergence to the surface is set in widely separated localities,

they agree in maintaining this to be the fourth plane on which

mankind has existed.

The following is an abbreviation of the version gathered by A.M.

Stephen, who lived many years among the Hopi and collected these

sacred tales from the priests and old men of all the different

villages some fifty years ago, as reported by Mindeleff.[20]

[Footnote 20: Mindeleff,

Cosmos, Traditional History of Tusayan (After A.M. Stephen): Bureau

American Ethnology, vol. 8, pp. 16-41, 1887.]

In the beginning all men lived together in the lowest depths, in a

region of darkness and moisture; their bodies were mis-shapen and

horrible and they suffered great misery.

By appealing to Myuingwa (a vague conception of the god of the

interior) and Baholinkonga (plumed serpent of enormous size, genius

of water) their old men obtained a seed from which sprang a magic

growth of cane.

The cane grew to miraculous height and penetrated through a crevice

in the roof overhead and mankind climbed to a higher plane. Here was

dim light and some vegetation. Another magic cane brought them to a

higher plane, with more light and vegetation, and here was the

creation of the animal kingdom. Singing was always the chief magic

for creating anything. In like manner, they rose to the fourth stage

or earth; some say by a pine tree, others say through the hollow

cylinder of a great reed or rush.

This emergence was accompanied by singing, some say by the Magic

Twins, the two little war gods, others say by the mocking bird. At

any rate, it is important to observe that when the song ran out, no

more people could get through and many had to remain behind.

However, the outlet through which man came has never been closed,

and Myuingwa sends through it the germs of all living things. It is

still symbolized, Stephen says, by the peculiar construction of the

hatchway of the kiva, in designs on the kiva sand altars, and by the

unconnected circle on pottery, basketry, and textiles. Doubtless the

most direct representation of this opening to the underworld is the

sipapu or ceremonial small round opening in the floor of the kiva,

which all Hopi, without exception, agree symbolizes the opening or

spirit passage to the underworld. “Out of the sipapu we all came,”

they say, “and back to the underworld, through the sipapu, we shall

go when we die.”

Once every year the Hopi hold an eight-day ceremony commemorating

this emergence from the underworld. It is called the Wu-wu-che-ma,

occurs in November and thus begins the series of Winter festivals.

Four societies take part, and the Da-dow-Kiam or Mocking Bird

Society opens the ceremony by singing into the kiva of the

One-Horned Society this emergence song, the very song sung by the

mocking bird at the original emergence, according to Voth.[21]

This ceremony is a prayer to the powers

of the underworld for prosperity and for germination of new life,

human, animal, and vegetable. Fewkes called this the New Fire

Ceremony, and in the course of the eight-day ceremonial the kindling

of new fire with the primitive firestick does take place.

But it is not hard to feel a close

relation between the idea of fire and that of germination which

stands out as the chief idea in the whole ritual, particularly in

the subtle dramatization of the underworld life and emergence as

carried on in the kivas, preceding the public “dance” on the last

day.

[Footnote 21: Voth, H.R., Op.

cit, p. 11.]

Thus we have at least three distinct

points in this one myth that account for three definite things we

find the Hopi doing today:

-

Note that it was “our old men” who

got from the gods the magic seed of the tall cane which brought

relief to the people. To this day it is the old men who are

looked up to and depended upon to direct the people in all

important matters. “It was always that way.”

-

While the magic song lasted the

people came through the sipapu, but when the song ended no more

could come through, and there was weeping and wailing. Singing

is today the absolutely indispensable element in all magic

rites. There may be variation in the details of some

performances, but “unless you have the right song, it won’t

work.” The Hopi solemnly affirm they have preserved their

original emergence song, and you hear it today on the first

morning of the Wu-wu-che-ma.

-

The sipapu seen today in the floor

of the kiva or ceremonial chamber symbolizes the passage from

which all mankind emerged from the underworld, so all the Hopi

agree.

The belief of the present-day Hopi that

the dead return through the sipapu to the underworld is based firmly

upon an extension of this myth, as told to Voth,[22] for it

furnishes a clear account of how the Hopi first became aware of this

immortality.

[Footnote 22: Voth, H.R., Op.

cit, p. 11.]

It seems that soon after they emerged from the underworld the son of

their chief died, and the distressed father, believing that an evil

one had come out of the sipapu with them and caused this death,

tossed up a ball of meal and declared that the unlucky person upon

whose head it descended should be thus discovered to be the guilty

party and thrown back down into the underworld. The person thus

discovered begged the father not to do this but to take a look down

through the sipapu into the old realm and see there his son, quite

alive and well. This he did, and so it was.

Do the Hopi believe this now? Yes, so they tell you. And Mr. Emery

Koptu, sculptor, who lived among them only a few years ago and

enjoyed a rare measure of their affection and good will, recently

told the writer of a case in point:

On July 4, 1928, occurred the death

of Supela, last of the Sun priests. Mr. Koptu, who had done some

studies of this fine Hopi head, was in Supela’s home town, Walpi,

at the time of the old priest’s passing.

The people were suffering from a

prolonged drouth, and since old Supela was soon to go through the

sipapu to the underworld, where live the spirits who control rain

and germination, he promised that he would without delay explain the

situation to the gods and intercede for his people and that they

might expect results immediately after his arrival there. Since his

life had been duly religious and acceptable to the gods, it was the

belief of both Supela and his friends that he would make the journey

in four days, which is record time for the trip, when one has no

obstacles in the way of atonements or punishments to work off

en-route.

Supela promised this, and the people

looked for its fulfillment. Four days after Supela’s death the long

drouth was broken by a terrific rain storm accompanied by heavy

thunder and lightning. Did the Hopi show astonishment? On the

contrary they were aglow with satisfaction and exchanged

felicitations on the dramatic assurance of Supela’s having “gotten

through” in four days. The most wonderful eulogy possible!

It is indicated, in the story of Supela, that the Hopi believe that

only the “pure in heart,” so to speak, go straight to the abode of

the spirits, whereas some may have to take much longer because of

atonements or punishments for misdeeds. Their basis for this lies in

a tradition regarding the visit of a Hopi youth to the underworld

and his return to the earth with an account of having passed on the

way many suffering individuals engaged in painful pursuits and

unable to go on until the gods decreed they had suffered enough. He

had also seen a great smoke arising from a pit where the hopelessly

wicked were totally burned up.

He was told to go back to his people and

explain all these things and tell them to make many pahos

(prayer-sticks) and live straight and the good spirits could be

depended upon to help them with rain and germination. Voth

records[23] two variants of this legend.

[Footnote 23: Voth, H.R., Op.

cit, pp. 109-119 (A journey to the skeleton house).]

Some Migration Myths

The migration myths of the various clans are entirely too numerous

and too lengthy to be in their entirety included here. Every clan

has its own, and even today keeps the story green in the minds of

its children and celebrates its chief events, including arrival in

Hopiland, with suitable ceremony.

We are told that when all mankind came through the sipapu from the

underworld, the various kinds of people were gathered together and

given each a separate speech or language by the mocking bird, “who

can talk every way.” Then each group was given a path and started on

its way by the Twin War Gods and their mother, the Spider Woman.

The Hopi were taught how to build stone houses, and then the various

clans dispersed, going separate ways. And after many many

generations they arrived at their present destination from all

directions and at different times. They brought corn with them from

the underworld.

It is generally agreed that the Snake people were the first to

occupy the Tusayan region.

There are many variations in the migration myths of the Snake

people, but the most colorful version the writer has encountered is

the one given to A.M. Stephen, fifty years ago, by the then oldest

member of the Snake fraternity. A picturesque extract only is given

here.

It begins:

“At the general dispersal, my people

lived in snake skins, each family occupying a separate

snake-skin bag, and all were hung on the end of a rainbow, which

swung around until the end touched Navajo Mountain, where the

bags dropped from it; and wherever their bags dropped, there was

their house. After they arranged their bags they came out from

them as men and women, and they then built a stone house which

had five sides.

“A brilliant star arose in the southwest, which would shine for

a while and then disappear. The old men said, ‘Beneath that star

there must be people,’ so they determined to travel toward it.

They cut a staff and set it in the ground and watched till the

star reached its top, then they started and traveled as long as

the star shone; when it disappeared they halted. But the star

did not shine every night, for sometimes many years elapsed

before it appeared again. When this occurred, our people built

houses during their halt; they built both round and square

houses, and all the ruins between here and Navajo Mountain mark

the places where our people lived. They waited till the star

came to the top of the staff again, then they moved on, but many

people were left in those houses and they followed afterward at

various times. When our people reached Wipho (a spring a few

miles north from Walpi) the star disappeared and has never been

seen since.”

There is more of the legend, but quoted

here are only a few closing lines relative to the coming of the

Lenbaki (the Flute Clan):

“The old men would not allow them to

come in until Masauwu (god of the face of the earth) appeared

and declared them to be good Hopitah. So they built houses

adjoining ours and that made a fine large village. Then other

Hopitah came in from time to time, and our people would say,

‘Build here, or build there,’ and portioned the land among the

new-comers.”[24]

[Footnote 24: Mindeleff, Victor,

Pueblo architecture (Myths after Stephen): Bureau American

Ethnology, vol. 8, pp. 17-18, 1887.]

The foregoing tradition furnishes the answer to two things one asks

in Hopiland. First, why have these people, who by their traditions

wandered from place to place since the beginning of time, only

building and planting for a period sometimes short, sometimes a few

generations, but not longer, they believe—why have they remained in

their present approximate location for eight hundred years and

perhaps much longer? The answer is their story of the star that led

them for “many moves and many stops” but which never again appeared,

to move them on, after they reached Walpi.

The second point is: The Flute Dance, which is still held on the

years alternating with the Snake Dance, is of what significance? It

is the commemoration of the arrival of this Lenbaki group, a branch

of the Horn people, and the performance of their special magic for

rain-bringing, just as they demonstrated it to the original

inhabitants of Walpi, by way of trial, before they were permitted to

settle there.

Flute Ceremony and Tradition

This Flute ceremony is one of the loveliest and most impressive in

the whole Hopi calendar. And because it is one which most clearly

illustrates this thesis, some detail of the ceremony will be given.

From the accounts of many observers that of Hough[25] has been

chosen:

[Footnote 25: Hough, Walter, Op.

cit., pp. 156-158.]

“On the first day the sand altar is