|

Even more so, it is

a startling epiphany to see this constellation rise out of the red dust of

the high desert as a stellar configuration of Anasazi cities built from the

mid-eleventh to the end of the thirteenth century. The sky looks downward to

find its image made manifest in the earth; the earth gazes upward,

reflecting upon the unification of terrestrial and celestial.

Mintaka, a double star and the first of the trinity to peek over the eastern horizon as the constellation rises, corresponds to Oraibi and Hotevilla on Third (West) Mesa. The former village is considered the oldest continuously inhabited community on the continent, founded in the early twelfth century.

As recently as 1906, the construction of the latter village proved to be a prophetic, albeit traumatic event in Hopi history precipitated by a split between the Progressives and the Traditionalists. About seven miles to the east, located at the base of Second (Middle) Mesa, Old Shungopovi (initially known as Masipa) is reputed to be the first village established after the Bear Clan migrated into the region circa A.D. 1100.

Its celestial

correlative is Alnilam, the middle star of the Belt. About seven miles

farther east on First (East) Mesa, the adjacent villages of Walpi,

Sichomovi,

and Hano (Tewa) --the first of which was settled prior A.D. 1300--

correspond to the triple star Alnitak, rising last of the three stars of the

Belt.

Due south of Oraibi about fifty-six miles is Homol’ovi Ruins State Park, a group of four Anasazi ruins constructed between the mid-thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

These represent the irregularly variable star Betelgeuse, the right shoulder of Orion. Almost forty-seven miles southwest of Oraibi is the primary Sinagua ruin of Wupatki National Monument, surrounded by a few smaller ruins. (“Sinagua” is the archaeological term for a group culturally similar and contemporaneous to the Anasazi.)

Built in the early twelfth century, their celestial counterpart is Bellatrix, a slightly variable star forming the left shoulder of Orion.

About fifty miles northeast of Walpi is the mouth of Canyon de Chelly National Monument. In this and its side Canyon del Muerto a number of Anasazi ruins dating from the mid-eleventh century are found. Saiph, the triple star forming the right foot or knee of Orion, corresponds to these ruins, primarily White House, Antelope House, and Mummy Cave. Extending northwest from Wupatki/Bellatrix, Orion’s left arm holds a shield over numerous smaller ruins in Grand Canyon National Park, including Tusayan near Desert View on the south rim.

Extending southward from Homol’ovi/Betelgeuse, Orion’s right arm holds a nodule club above his head.

This club stretches across the Mogollon Rim and down to other

Sinagua ruins

in the Verde Valley. As a small triangle formed by Meissa at its apex and by

Phi 1 and Phi 2 Orionis at its base, the head of

Orion correlates to the Sinagua ruins at Walnut Canyon National Monument and a few smaller ruins in

the immediate region.

The apparent distances between the stars as we see them in the constellation (as opposed to actual light-year distances) and the distances between these major Hopi village or Anasazi/Sinagua ruin sites are close enough to suggest that something more than mere coincidence is at work here.

For instance, four of the sides of the heptagon

are exactly proportional, while the remaining three sides

are slightly stretched in relation to the constellation-- from ten miles in the case of D. and E. to twelve miles in the case of G. (See Diagram 1.)

Diagram 1 This variation could be due either to cartographic distortions of the contemporary sky chart in relation to the geographic map or to ancient misperceptions of the proportions of the constellation vis-à-vis the landscape.

Given the physical exigencies for building a village, such as springs or rivers, which are not prevalent in the desert anyway, this is a striking correlation, despite these small anomalies in the overall pattern.

As John Grigsby says in his discussion of the relationship between the temples of Angkor in Cambodia and the constellation Draco,

In this case we are dealing not with Hindu/Buddhist temples but with multiple “star cities” sometimes separated from each other by more than fifty miles.

Furthermore, we have suggested that the “map” is actually

represented on a number of stone tablets given to the Hopi at the beginning

of their migrations, and that this geodetic configuration was influenced or

even specifically determined by a divine presence, viz., Masau’u, god of

earth and death.

Using Bersoft Image Measurement 1.0 software, however, we can correlate in degrees the precise angles of this pair of digital images seen in the diagram. (Note: The celestial image is drawn from Skyglobe 2.04.)

The closest correlation is between the left and right shoulders (BC and DE respectively) of the terrestrial and celestial Orions, with only about two degrees difference between the two pairs of angles.

In addition, the left and right legs (AG and FG respectively) are within the limits of recognizable correspondence, with approximately six to eight degrees difference. The only angles that vary considerably are those that represent Orion's head (CD), with over fifteen degrees difference between terra firma and the firmament.

Given the whole polygonal configuration, however, this discrepancy is not enough rule out a generally close correspondence between Orion Above and Orion Below.

According to their cosmology, the Hopi place importance on intercardinal (i.e., northwest, southwest, southeast, and northeast) rather than cardinal directions. Of course, the Anasazi could not make use of the compass but instead relied upon solstice sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for orientation.

The Sun Chiefs (in Hopi, tawa-mongwi) still perform their observations of the eastern horizon at sunrise from the winter solstice on December 22 (azimuth 120 degrees) through the summer solstice on June 21 (azimuth 60 degrees), when the sun god Tawa is making his northward journey.

On the other hand, they study the western horizon at sunset from June 21 (azimuth 300 degrees ) through December 22 (azimuth 240 degrees), when he travels south from the vicinity of the Sipapuni (located on the Little Colorado River just over four miles upstream from its confluence with the Colorado River) to the San Francisco Peaks in the southwest. 2.

A few

days before and after each solstice Tawa seems to stop (the term

solstice

literally meaning “the sun to stand still”) and rest in his winter or summer

Tawaki, or “house.” In fact, the winter Soyal ceremony is performed in part

to encourage the sun to reverse his direction and return to Hopiland instead

of continuing south and eventually disappearing altogether.

The sun disappears over Humphreys Peak, the highest mountain in Arizona where is located the major shrine of the katsinam (also spelled kachinas, beneficent supernatural beings who act as spiritual messengers).

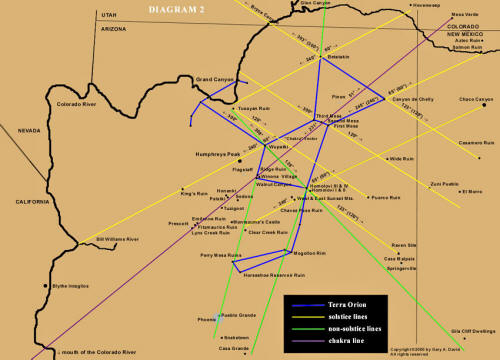

Incidentally, if this line between Oraibi and the San Francisco Peaks is extended southwest, it intersects the small pueblo called King’s Ruin in Big Chino Valley, a stop-off point on the major trade route from the Colorado River. 3. (See Diagram 2.)

If the line is extended farther southwest, it intersects the mouth of Bill Williams River on the Colorado. Conversely, if we stand at Wupatki on the summer solstice, we can see the sun rise directly over Oraibi on Third Mesa at 60 degrees on the horizon. On that same day the sun would set at 300 degrees, to which the left arm of the terrestrial Orion points.

In addition, from Oraibi the summer solstice sun sets at 300 degrees, twelve degrees north of the Sipapuni on the Little Colorado River, the “Place of Emergence” of the Hopi from the Third to the Fourth Worlds.

Diagram 2 Solstice relationships between villages

After going east, if we were to perch on the edge of Canyon de Chelly and not look downward into the canyon but instead southwest at the winter solstice sunset, the sun on the horizon would appear about five degrees south of the First Mesa Village of Walpi.

If this line were extended farther southwest beyond the horizon, it would intersect both Sunset Crater and Humphreys Peak. Again, the reciprocal angular relationship between the two pueblo sites remains, so from Walpi at summer solstice sunrise the sun would appear to rise from Canyon de Chelly fifty miles away.

A northeastward extension of this 65 degree line would eventually reach a point in New Mexico near Salmon Ruin and Aztec Ruin. 4.

In addition, a winter solstice

sunrise line (120 degrees) drawn from Walpi past Wide Ruin traverses the

Zuni Pueblo (a tribe closely related to the Hopi) and ends just south of El Morro National Monument.

5.

Later on that first day of winter from the same spot at Tsegi Canyon we could see the sun set at 240 degrees azimuth over the Grand Canyon more than eighty miles to the southwest. From Tsegi a summer solstice sunrise line of 60 degrees would intersect Hovenweep National Monument in southeastern Utah, well known for the archaeoastronomical precision of its solstice and equinox markers.

Again

from Tsegi a sunset line of 300 degrees would cross Bryce Canyon National

Park and Paunsaugunt Plateau, where nearly one hundred and fifty small Anasazi and Fremont ruins have been identified.

7.

Again, from the reciprocal village of Wupatki the winter solstice sun would rise just north of Homol’ovi, which is

at 128 azimuthal degrees in relation to the former site. This Wupatki-Homol’ovi line extended southeast would pass just south of Casa

Malpais Ruin and end less than ten miles south of Gila Cliff Dwellings.

8.

From Homol’ovi at winter solstice sundown (240 degrees), the sun passes directly through East and West Sunset Mountains, the gateway to the Mogollon rim. This line from Homol’ovi proceeds past the early fourteenth century, thousand-room Chavez Pass Ruin on Anderson Mesa (in Hopi, Nuvakwewtaqa, “mesa wearing a snow belt”) 11. and continues along the Palatkwapi Trail down to the Verde Valley, ending near Clear Creek Ruin.

If we extend the summer solstice

sunrise line (60 degrees) from Homol’ovi into New Mexico, we intersect the

vicinity of Chaco Canyon, perhaps the jewel of all the Anasazi sites in the

Southwest. In this astral-terrestrial pattern Chaco corresponds to

Sirius,

the brightest star in the heavens located in Canis Major.

This interrelationship provided a psychological link between one’s own village and the people in one’s “sister” village miles away. Moreover, it reinforced the divinely ordered coordinates of the various sky cities come down to earth.

Not only did Masau’u/Orion speak in a geodetic language that connected the Above with the Below, but also Tawa verified this configuration by his solar measurements along the curving rim of the tutskwa, or sacred earth.

|