|

from

TheOrionZone Website Across ocher and salmon colored sandstone a shadow crawls like a shallow pool of water flowing in slow motion.

Its fuzzy penumbra gradually slides over the spiral petroglyph pecked into smooth rock. We know this movement is the result of the greater spinning of our planet in relation to a stationary sun. However, for the Hisatsinom (a.k.a. the Anasazi) shadows were animate beings whose movements reflected those of the Underworld spirits.

The Pueblo people conceived of the spirit world as being coterminous

with the chthonic zone of the previous Third World,

Thus, the duality of light and dark, day and night, summer and winter, etc. inherent in the Hisatsinom cosmology was infused with an animism that allowed the great sun god Tawa to interact with the lesser dusky revenants who periodically return from the subterranean realms via the various manifestations of the Sipapu.

For us the importance of such a natural phenomenon is mostly esthetic, exemplified by lavish Sierra Club photography depicting shadows which play across sensuously curving sandstone sunlit in stark, vibrant colors.

For the Ancient Ones, however, shadows were supernatural 'shades' imbued with a mysterious vitalism that imparted not only beauty in the eye of beholder but awe as well.

Four major ruin sites and a few outlying sites exist in the vicinity of Homol’ovi Ruins State Park near Winslow, Arizona.

On the east side of the Colorado River we find Homol’ovi I and II; on the west side of the river are Homol’ovi III and IV, all settled at slightly different periods. Homol’ovi IV, a 150 room masonry pueblo built in a stepwise manner on the east and south sides of a small butte as well as on its top, was the settled in A.D.1260 by immigrants from the Hopi Mesa region.

It was occupied only for a period of twenty

years, which might have been the result of an influx of clans moving

from the south to build some of the other sites at Homol’ovi.

3

Because of the style of ceramics found --black-and-white painted on red ware-- plus the larger room construction of masonry and puddled adobe 4, archaeologists hypothesize that the builders of this pueblo were Mogollons who migrated from the Silver Creek region of eastern Arizona near the contemporary towns of Snowflake and Showlow.

As with Homol’ovi IV, this pueblo’s life span was brief; it

was abandoned in the early 1300s due to the extensive flooding which

followed the Great Drought of 1276-1299, the earlier event perhaps

partially causing the migration to Homol’ovi III in the first place.

Some portions of Homol’ovi I were two stories high, and it also contained a number of open plazas and kivas.

One of the latter measuring fourteen feet wide and twenty

feet long was paved with flagstones and had a stone bench on the

south end and a number of loom holes on the east and west sides.

This highly stratified pueblo which used a variety of masonry and

adobe construction styles suggests much renovation during its

relatively long history. It was abandoned in circa A.D. 1390 after a

period of massive flooding.

In addition to numerous representations of these spirit

beings on ceramic bowls and petroglyphs, two beautifully painted

murals were found on the walls of two separate kivas at Homol’ovi II:

one depicts the San Francisco Peaks where the katsinam live, while

the other shows two katsina dancers with cotton kilts. Homol’ovi II

was abandoned at about the same time as Homol’ovi I near the end of

the fourteenth century.

Approximately ten feet to the east is a round-topped boulder that forms the inner east wall of the enclosure and casts a curved shadow upon the main panel.

Open to the south but blocked to the north by broken chunks of rock heaped higher than their heads, this enclosure protects the observers who sit cross-legged and close together on the ground, gazing in rapt attention at the primary grouping of petroglyphs on the main panel.

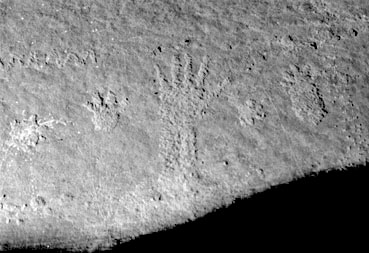

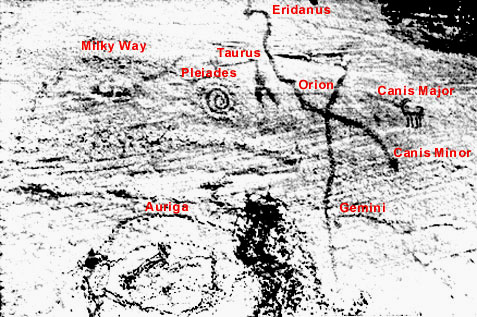

Earth/star map and solar maker petroglyph panel at Homol'ovi On the left (south) side of this panel near the bottom are clan markings. These include a bear print, a human left hand print, possibly a badger claw (all arranged horizontally), and a snake glyph looping horizontally above these (photo below).

Clan markings on left side of main panel. Just to the right of this grouping is a long migration line that curves upward and to the right, ending in a spiral comprised of four revolutions.

Near the bottom of the panel immediately to the right of this "trail" is a somewhat circular "corral" that contains a zoomorph in profile. Its head faces obliquely upward and to the right. In between the trail and the left side of the corral is a vertical zigzag snake, while on the left side is a pair of similar zigzag snakes, all of which have recently been defaced.

Slightly above and a few inches to the right of the spiral is a glyph depicting some sort of V-shaped "artifact" pointed downward.

To the right of this we find a large equilateral cross formed by an oblique axis we shall call the "plumed serpent," carved from the top left to the lower right of the panel. A "vertical axis" bisects this oblique line and extends downward to nearly the same height as the bottom of the corral, ending in a cupule about one inch in diameter.

To the

far right (or north) at the same height as the center of the cross,

there is a petroglyph of an antelope - a pronghorn in profile with

its head facing to the left. Viewed as a composite, these petroglyphs are about eight feet long.

Within a few moments orange sunlight bathes the top of the main panel, while the eastern wall of the enclosure begins to cast a gently arcing, horizontal shadow.

Soon this shadow-being

starts to crawl down the panel, passing consecutively through a

number of petroglyphs: the head of the plumed serpent, the center of

the spiral, the V-shaped artifact, the intersection of the cross,

the antelope, the corral, and the clan petroglyphs on the far left.

One section on this generally horizontal shadow has two right angle

jogs that first nestle the plumed serpent’s head as they pass

through and then follow the slight curve on the upper portion of the

vertical axis.

Chants to both the sun god Tawa and the chthonic spirits accompany this “sacred appearance,” as an aura of the miraculous pervades the gradually warming air of morning.

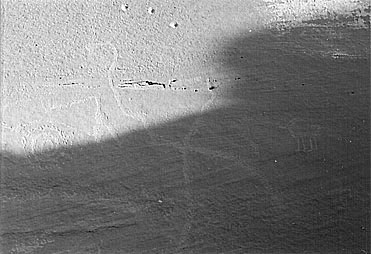

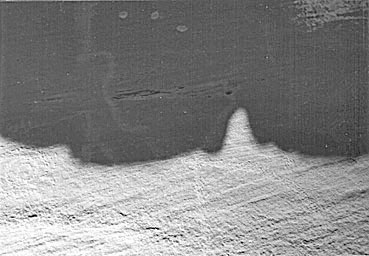

Horizontal shadow cast by the round-topped boulder 10 feet to the east of the main panel. Shadow passes through spiral on left, touches the tips of the V-shaped artifact, and jogs around the top of the vertical line. Note antelope center right.

The three

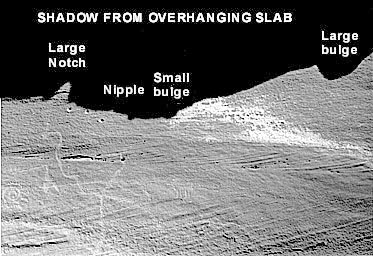

indentations at the top center appear to be bullet holes. Just as this shadow creature is departing, another one formed by the overhanging slab begins to proceed down a yet unmentioned pair of vertical rows of dots which are located at the very top right of the panel.

Each row contains either twenty or twenty-one pecked dots, but erosion now makes it impossible to determine the exact number. Because of the irregularities on the edge of the horizontal slab overhead, its adumbration has a number of bumps and notches that interact with specific petroglyphs during various stages of the spectacle. (See Diagram 1 far below.)

In comparison with the former

shadow discussed, this one will create a dynamic synergy of sunlight

and shade that staggers the mind. Not unlike a written account of

the movements in a ballet or --more germane to our discussion-- the

ritual acts of a katsina dance, any description of this presentation

is bound to fall short of its actual intricacy and sanctity. In

other words, the play’s the thing.

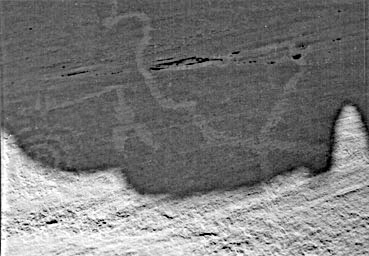

At 8:45 a.m. as it reaches the bottom of these rows, the “small bulge” is poised directly above the antelope, the “nipple” rests above the vertical axis, and the “large notch” hovers above the head of the plumed serpent.

Shadow cast by the overhanging ledge. Large bump on the far right at the end of two vertical rows of dots (not visible in photo). Smaller bump above the antelope (center of photo). Nipple above the vertical line.

Large notch on the left above the head of the plumed serpent.

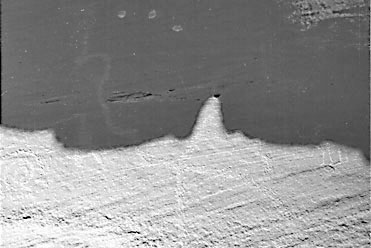

Nearly an hour later the horizontal section of the shadow to the right of the large notch bisects the antelope, while the horizontal section to the left bisects the V-shaped artifact.

At this point the notch itself is lodged on top of the vertical axis.

Shadow bisects both the antelope on the right and the V-shaped artifact on the left.

The large notch is lodged on top of the

vertical line that terminates in the faint cross (star) and a

natural hole. After five minutes this same horizontal section to the right reaches the feet of the antelope, while the horizontal section to the left touches the lower tip of the artifact.

Simultaneously, the lower left side of the notch is almost at the center of the cross. In addition, a smaller notch which has formed to the left of the larger one is lodged between the artifact and the spiral.

Furthermore, the curving shadow to the left of this smaller notch grazes the upper part of the spiral.

On the left the shadow grazes the upper arc of the spiral and touches the tips of the V-shaped artifact. The notch continues toward the lower right down the serpent.

On the right the shadow

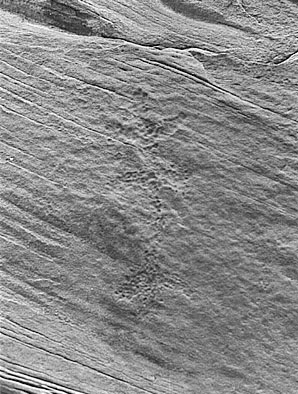

rests at the feet of the antelope (obscured by shadow). In seven minutes the left side of the shadow reaches the center of the spiral, and the large notch begins traveling down the lower part of the oblique plumed serpent.

Left side of shadow in the center of spiral and notch continues down

oblique line (serpent).

Approximately twenty minutes later the large notch reaches the end

of the plumed serpent, while the left side of the shadow touches the

outer left curve of the spiral, where it will remain for nearly two

more hours.

Left side of shadow rests on the left side of spiral.

Notch reaches

the tail of the serpent at lower right. After about another half hour, the horizontal lower edge of the whole shadow has moved off the panel, though its left side still rests on the left side of the spiral.

At about 12:30 p.m. this triangle splits into two smaller triangles of light. When these lights pass directly into the center of the spiral, however, they merge.

Small triangle of light forms at upper left as vertical shadow begins to move to the right toward center of spiral.

Triangle of

light continues downward through center of spiral. This one triangle proceeds downward and passes out of the spiral, where it again splits into two smaller triangles of light. The left side of the whole shadow is now passing through the corral, the only time it is obscured.

Triangle of light continues downward and leaves spiral. Horizontal portion of shadow continues downward through the corral

until

finally the main panel is no longer illuminated. Thus far we have been witnessing an unequivocal hierophany.

For approximately seven and a half hours we have seen the worlds of shadow and sunlight interact with amazing complexity, evoking beyond a doubt the discernible presence of the divine.

But while the bottom of the shadow touches the bottom of the corral, and with most of the main panel no longer illuminated, something startling occurs. Just when we think that the sacred show is over, the light leaves the main panel and leaps across to the smaller panel opposite it, i.e., the inner east wall of the rock enclosure.

A crescent of light with down-turned cusps hovers over a petroglyph representing an artifact comprised of four crescents arranged on a vertical shaft.

At its top is a small circle, and just beneath that is a crescent with upturned cusps that mirrors the crescent of sunlight with breathtaking congruence.

On a smaller panel opposite main panel, a vertical artifact with perpendicular crescents.

After sunlight leaves the main panel, it hovers over top crescent of artifact.

(Petroglyph dampened to

accentuate features.) This artifact is located directly across from the V-shaped artifact on the main panel.

To the right of the former artifact is a zoomorph which is also directly across from the one inside the corral on the main panel. To the right and a few feet below this animal on the smaller panel is a “double rainbow” with a dot in the middle, which is across from the clan markings on the main panel.

Between the droning chants of the sun priest and his offerings of corn meal and paho feathers, he has been explaining to the people of the village the subtle ritual performed jointly by the sun god and the Underworld spirit shadows.

Now on this longest day of the year when Tawa again begins his

southward journey along the sunrise and sunset horizons, the balance

of the world is once more restored.

Let us discuss the discrete elements of

this configuration of rock art, looking at the cultural symbology of

each separate petroglyph.

Some believe that the spiral represents the shaman’s tunnel or portal though which spirit journeys are made.

In the context of Pueblo culture this would signify the passage via the sipapu between the Third and the Fourth World. It is easy to imagine why the spiral would also be associated with whirlpools in water and whirlwinds in air.

Polly Schaafsma, an expert in the field of rock art, has given a number of interpretations for this ubiquitous petroglyph of the Southwest:

This latter comment is especially true if the end of the spiral is extended into a “trail,” which is precisely the case of the spiral at Homol’ovi we have discussed.

This is connected to a very long, curving path that terminates at a number of clan petroglyphs, in particular the Bear, the Snake, and perhaps the Badger. The loops of the spiral are also thought to represent the number of rounds or pasos made in ancient migrations to each of the four directions. 7

One interpretation closely associates this petroglyph with a primary Hopi deity:

One source geographically particularizes the symbology of the spiral by relating it directly to the Sipapu in Grand Canyon and the Hopi salt gathering ceremony performed there.

Thus, in this context the spiral/whirlpool is known as “the gate of Masau’s house.”

This is an important element in constructing the stone

“map,” the solstitial aspects of which are described earlier in

Chapter 5 (not shown).

Of course, small equilateral crosses represent stars, but this larger one could be construed as a modified swastika, a common symbol in Anasazi, Sinagua and Mogollon iconography for the land, especially the center of the land. 10

One intriguing variation of the Homol’ovi cross can be found in its oblique axis, which we have labeled the “plumed serpent.”

In the Pueblo frame of reference, snake iconography represents rivers in particular and water in general - perhaps in part because the reptilian resembles the riparian morphologically.

If the Anasazi/Hisatsinom were lucky (or more correctly, punctilious in regard to their ceremonial cycle), lightning was accompanied by copious amounts of rain. As the northern equivalent of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl or the Mayan god Kukulkan, the plumed (or horned) serpent, called Palulukang by the Hopi, acts as a guardian of underground springs.13

Furthermore, it serves as a universal provider, offering its bounty in a land of scarcity.

This hybrid creature unites the three planes of subterranean, terrestrial, and celestial by its corresponding characteristics of reptile, mammal, and bird.

Especially in the

desert the serpent symbolizes liquid life itself, either as an

indispensable potable substance (i.e., the primordial milk of

existence) or as a vital fluid flowing through the veins of all

beasts.

This correlates to the ruins of Betatakin and Kiet Siel in Tsegi Canyon within the borders of Navaho National Monument due north of the Hopi Mesas. Approximately the same number of inches below the intersection point, just to the right of the vertical axis, is a faint mark in the rock that represents Homol’ovi itself.

If the Hopi Mesas were indeed first settled circa A.D. 1100, then

the Hisatsinom living at this spot where the petroglyph is located

would have certainly recognized the well-established Center-place

off to the north, since this first settlement at Homol’ovi is dated

A.D. 1260. Incidentally, Betatakin and Homol’ovi are equidistant on

this north-south axis and were built at about the same time.

The tip of the serpent’s tail might correspond to the ruins at Casa Malpais and Raven Site in the southeast near the source of the Little Colorado. To the left on the upper portion of the oblique axis midway between the intersection and the serpent’s head is a right angle turn that represents the Wupatki pueblos, built in the first few decades of the twelfth century just after the Hopi Mesas were initially settled. Moreover, the serpent's head could be linked with the smaller ruins of Glen Canyon along the Colorado River north of the Grand Canyon.

As an extension of the spiral, the “trail” roughly follows the geographic arcing of the Colorado River as it flows downstream, terminating at a number of clan petroglyphs, in particular the Bear Clan and the Snake Clan. As acknowledged in Hopi oral tradition, the migration from the Third to the Fourth World entailed the use of bamboo boats to escape a tremendous flood.

Some believe that the Hisatsinom traveled upstream

and through the Grand Canyon to arrive at the Sipapuni, at which

place they emerged to seek their final destination upon the Colorado

Plateau.

The three Hopi Mesas were next settled, with Shungopovi on second Mesa established circa A.D. 1100 and Oraibi on Third Mesa shortly thereafter (Some versions, however, state that the villages were constructed in reverse order.) Shungopovi’s corresponding star is Alnilam with a magnitude of 1.7, while Oraibi’s is Mintaka with a magnitude of 2.2.

Walpi supposedly was settled in the late 1200s, but the village of Koechaptevela at the base of First Mesa preceded the existence of the former village, so its date of origin may have coincided with those of Shungopovi and Oraibi. At any rate, the correlative star of First Mesa is Alnitak with a magnitude of 1.79, approximately that of Alnilam.

To the southwest Wupatki was established about A.D. 1120, and its sidereal twin is Bellatrix, which has a magnitude of 1.64.

Thus, we can perceive the northeast-southwest axis as part of the oblique line of the petroglyph. To the south of the Hopi Mesas Homol'ovi IV was established in A.D. 1260, and its sidereal companion is Betelgeuse, whose magnitude is 0.7. (However, because it is a variable star it sometimes appears as bright as Rigel.)

To the north is Betatakin, built in A.D. 1260 as well. Its correlative is Rigel with a magnitude of 0.34. Now we can also perceive the north-south axis as part of the vertical line of the petroglyph. The reader may have noticed a proportional relationship between the age of the pueblo villages and the magnitude of each village’s corresponding star.

Specifically, we find that the relative age of a given ruin or extant village is for the most part in inverse proportion to the magnitude of its sidereal correlative. In other words, the older the village the dimmer the star. (We must remember that a lower magnitude number signifies a greater sidereal brilliance.)

To recapitulate, the oldest villages like those in Canyon de Chelly have the dimmest stars (i.e., Saiph), while the youngest villages like those at Homol’ovi and Tsegi Canyon have the brightest stars (i.e., Betelgeuse and Rigel respectively). Again we must decide whether or not this coincidence is “meaningful.”

Perhaps it is indeed another part of the elegant pattern in which the terrestrial mirrors the celestial.

Diagram 1 We have seen how the large equilateral cross of the Homol’ovi petroglyph represents both the Hopi Mesa villages at the Center-place and the ruins sites at Tsegi Canyon, Wupatki, Homol’ovi, and Canyon de Chelly.

This Anasazi swastika symbolizing the land also mirrors the sky, specifically the constellation Orion. The oblique line forming a plumed serpent corresponds to the Little Colorado River, which flows into the Grand Canyon.

We have also established that the spiral glyph signifies the gate through which Masau’u descends to his house located just north of the two great rivers’ convergence. This is the grand Sipapu, whence the people emerged onto the Fourth World where they now live. On a personal level this is also the passage way through which the spirit will descend on its afterlife journey.

Equidistant between the plumed serpent and the spiral is an image we have not yet discussed. A V-shaped artifact points downward, enigmatically radiating its numinous power.

If we look at a sky chart in the region of Orion, we notice that the V-shaped Hyades of the constellation Taurus lies adjacent to Orion in the same relative positioning that we find on the petroglyph. The relationship between Taurus, in particular the fiery red star Aldebaran, and Sotuknang, the Heart of the Sky God, is an enduring theme in Hopi mythology.

Hence, on this one petroglyph panel at Homol’ovi we unequivocally find elements that iconographically link both the celestial and the terrestrial.

In addition to the petroglyphic

constellations of Orion and Taurus, to the left of the V-shaped

glyph is located the spiral, which perfectly corresponds on the sky

chart to the Pleiades, known to the Hopi as either Tsöötsöqam or

Sootuvìipi. 17

Thus we have here three glyphs in a row which

directly correspond to the configuration of three major

constellations.

Looking to the sky chart in the same relative position, we find the brightest star in the heavens, Sirius in Canis Major.

We should note here that in Hopi cosmology the intercardinal direction of southeast is totemically represented by the antelope. 19

East of First Mesa nearly 140 miles are the ruins of a grand

ceremonial city in Chaco Canyon, which is represented in a

proportional distance on the Homol’ovi petroglyph by this

appropriate zoomorph.

On an extension of the vertical line just below a gentle curve are two abraded marks on either side of the line. The line continues downward until it terminates in an abraded mark made inside a natural cupule. A few inches to the right of this is another slightly larger natural cupule. Looking at the sky chart, we find this corresponds to the rectangular constellation Gemini.

The upper pair of marks represents Alhena and Mu Gemini, while the lower pair Pollux and Castor, known to the Hopi as Naanatupkom, or “the Brothers.” 20 Perhaps it is merely a coincidence, but a natural groove in the panel cuts horizontally just below Betelgeuse and above Alhena. Terrestrially this could correspond to the Mogollon Rim cutting across the middle of Arizona, while celestially this might signify the Milky Way, which the Hopi call Soomalatsi. 2 1

In

addition, the tip of the plumed serpent’s tail which we said

plausibly represents the region the Hopi deem Weenima

22 (the ruins

at Casa Malpais and Raven Site) may very well correspond to the

constellation Canis Minor with its bright star Procyon, known to the

Hopi as Taláwsohu, or “Star Before the Light.”

23

More recently the zoomorph inside the corral has been badly defaced, so it is difficult to determine its species, but quite possibly it could represent a mountain goat or mountain sheep. Having the exact magnitude of Rigel, the brightest astral point of this constellation is Capella, which means “little she-goat.” 24

The zoomorph inside the corral could indeed be

a mountain goat or a mountain sheep, the latter of which is the Hopi

totemic symbol for the southwest-- the direction where the

terrestrial Auriga would be located in our constellatory schema.

Initially one is enraged at such wanton destruction of rock art, but since these zigzag elements do not seem to fit either the conceptual configuration as we have described it or the style of the rest of the petroglyph panel, perhaps this was an intentional defacement. Possibly some modern Hopi tried to erase the negative spiritual effect of such spurious graffiti made in more recent times, probably by a non-Indian.

As with most rock art, a mysterious conundrum

supersedes any such speculations.

In terms of the tellurian dimension, represented by the large equilateral cross are the villages of the Hopi Mesas as well as the ruins located at Navaho National Monument, Wupatki National Monument, Homol’ovi Ruins State Park, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. What we have called the plumed serpent represents the Little Colorado River and the on the left side of the panel the V-shaped artifact corresponds to all the smaller ruins in the Grand Canyon. On the right side of the panel the antelope signifies the magnificent Anasazi/Hisatsinom ruins in Chaco Canyon.

The spiral corresponds to the Hisatsinom’s Place of Emergence in the Grand Canyon, while its extension represents the Colorado River flowing southward.

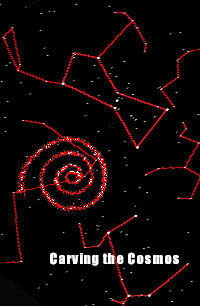

Constellations on the main petroglyph panel proportional to the sky chart.

Such is the beauty of this elegant schema. Students of mythology frequently try to find specific terrestrial locations for various myths, and sometimes they do, as in the case of the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann unearthing the city of Troy at Hissarlik in modern-day Turkey.

On the other hand, Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, co-authors of the masterful and scholarly Hamlet’s Mill, steer us in the opposite direction, i.e., skyward. They contend that a number of consistent mythological motifs from places as diverse as Iceland, Finland, Polynesia, India, and Iran correspond to various celestial phenomena, in particular the precession of the equinoxes.

Using the Icelandic version of the legend as a one variant of the famous Hamlet figure, they summarize their theory:

In the context of our star map petroglyph, this all seems vaguely familiar. In lieu of the marine location found in many of the mythic renditions, our desert “mill” located at the bottom of Grand Canyon is represented by the spiral or whirlpool.

Also known as the gate of Masau’u, it leads to the land of the dead. The Lord of the Mill in one variation is Saturn/Kronos 26, who is archetypally related to the Hopi god of the Underworld named Masau’u.

The direction of the mill was generally thought to be northwest,

At this point we probably

don’t need to be reminded that the Sipapu is located northwest of

the Hopi Mesas.

Although the Hopi Tuuwanasavi is not

directly coextensive with the whirlpool of the Grand Canyon, it is

contiguous, and, given the wide range of Anasazi/Hisatsinom

migrations, close enough to be conceptualized as part of the

Center-place.

This theme is related to the image of the “Saltwater-Tree” of the Cuna Indians who live in Panama as well as on the San Blas Islands, and whose ancestors conceivably had trade relations with the Anasazi/Hisatsinom “God’s whirlpool” is located beneath this tree, which, when chopped down by Tapir (a sun god somewhat resembling Quetzalcoatl), unleashes a great flood to form the world’s oceans. 29

As recalled in Hopi mythology, a mighty

deluge caused the destruction of the Hopi Third World.

Instead of an

actual tree, which is not a very potent image in the cosmology of

desert dwellers, a hollow bamboo reed through which the virtuous

people emerged from the lower Third to the upper Fourth World

finally comes crashing down (or is cut down), leaving the wicked

either imprisoned inside it or stranded below in the nether realm.

This root extends into Niflheim, the dark abode of the Underworld, and is gnawed upon by Nídhögg, a flying dragon who also slowly devours the bodies of the dead. 30 As we have stated, the plumed serpent is represented by an oblique line on the petroglyph. If we conflate Palulukang and Masau’u/Orion, contained therein is the vitalizing force of water and the mortuary aspect of a subterranean denizen, both of which we find in the figure of Nídhögg.

Incidentally, the harts nibbling on the shoots of Yggdrasil could plausibly correspond to the zoomorphs on the Homol’ovi petroglyph.

Petroglyph found in the vicinity of the earth/star map.

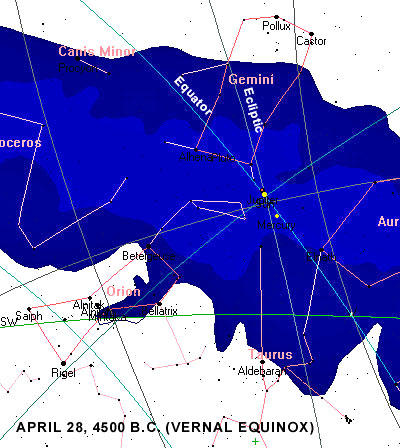

Santillana and Dechend also discuss in sidereal terms the Platonic cosmology found in the Timaeus.

In addition to a swastika’s representation of land, the chiasmic icon of the star petroglyph might also jointly refer to the celestial equator and the ecliptic.

As heretofore stated, the former currently passes very near Oraibi/Mintaka, while the latter always passes through Gemini, just above the right hand of Orion and between the horns of Taurus.

The precise location in the night sky of the latter was once, a very long time ago, also the fiducial point, i.e., the place where the equator crosses the ecliptic. At the present this locus is located between Pisces and Aquarius-- hence we are entering the celebrated “Age of Aquarius.” However, about 6,500 years ago the fiducial point of the vernal equinox was located between Gemini and Taurus with the Milky Way passing directly through it.

For the Anasazi/Hisatsinom this date, archaeologically speaking, places it squarely in the middle of the Archaic period. For the Hopi this may correspond to the First World, the pristine era of the cosmogony. For classical writers it was the Golden Age. The 5th century A.D. Latin grammarian and philosopher Macrobius states that during this age souls ascended through the “Gate of Capricorn” and descended to be reborn through the “Gate of Cancer.” 32

Because of the precession of the equinoxes caused by the slight wobble of the Earth’s axis, these respective gates in fact are located between Scorpius and Sagittarius on one end of the Milky Way and Taurus and Gemini on the opposite end. In terms of our star petroglyph the forked icon represents Taurus (recalling the Chinese “Gate of Heaven”), located terrestrially in the the Grand Canyon, which, as we have stated, is an important pathway for the katsinam or spirits in their afterlife journey.

Thus, in 4500 B.C. the place where the celestial equator crosses the ecliptic was at the heart of the galactic plane.

This “stargate,” so to speak, functioned as an interdimensional portal through which souls could pass into this life.

Stargate, where the celestial equator crosses the ecliptic at the center of the galactic plane, or the Milky Way. The green line is the western horizon.

Incidentally, on this date the Sun is conjunct

Jupiter, a strongly individualistic and optimistic aspect. In discussing our star map petroglyph vis-à-vis contemporary notions of cartography, we must remember that the former is conceptual rather than proportionally representational.

Archaic societies were not interested in producing scale maps of either the earth or the sky.

For a rendering of mythic symbology in rock art it was sufficient to contain merely the essential elements, as does the petroglyph at Homol’ovi.

The spiral of our star petroglyph is probably closer to the left shoulder of Orion than the left foot, but the significance of the icon still remains.

The Greek word zalos may be related to a combination of the intensive za- and the eleventh letter of the Greek alphabet lambda, which is V-shaped-- thus indicating Taurus and the V-shaped artifact.

The great sage Hermes Trismegistus (whose Egyptian name was Thoth) states that the stars near Rigel signify death, and this is borne out in Anasazi/Hisatsinom cosmology by the glyphic depiction of the Grand Canyon, the great Sipapu.

The name Eridanus literally means “the river,” and head of the plumed serpent

could indeed represent the upper Colorado River. The plume on the

snake’s head extended vertically for a few feet could possibly even

correspond to the Green River which flows from the north to join the

Colorado River in Utah.

Manifesting a stunning complexity and beauty, this example of rock art carved probably in the late thirteenth century serves as both a terrestrial cartography associated with the migrations of various clans and a sky chart establishing the template of Orion and other constellations upon the earth.

In addition, it is an highly

accurate solstice marker announcing the longest day of the year when

the sun god Tawa reaches his summer house on the northeastern

horizon. The purpose of the two parallel rows of dots at the top

right of the main panel is at present undetermined, but may yet

prove to have some supernal function, perhaps lunar.

Beyond the

academic speculations it engenders, this rock surface provides a

dream screen upon which we project our desires for a unified

cosmology complete with its holistic framework of ritual and myth.

For its makers, on the other hand, the petroglyph panel was

undoubtedly a manifestation of the numinous forces inherent in a

vibrant world where the membrane between the physical and the

spiritual was as diaphanous as a breath.

Do we not, as a result, have a tendency to look back through the distorted lens of temporal chauvinism with some measure of pity for the brief life span of these so-called primitive people?

In an age of chaos when “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” 35 and the world appears to be on the brink of an absolute holocaust, are we not the ones instead who should be pitied?

The carved rock at Homol’ovi remains stoically

silent - the enduring recurring rhythms of sunlight and shadow its

only refrain.

|

accessed

primarily through the Sipapu at the bottom of the Grand Canyon just

east of the confluence of the Colorado and the Little Colorado

Rivers.

accessed

primarily through the Sipapu at the bottom of the Grand Canyon just

east of the confluence of the Colorado and the Little Colorado

Rivers.