|

On 8 January last year, around 6.45pm, residents of

Delaware in the US were

startled by a sonic boom, strong enough to shake walls, rattle windows and

cause the citizens to call their local police offices, demanding

explanations. This particular speeder, however, could not only outrun any

highway-patrol cruiser in Delaware, but was beyond the reach of anyone else

in the state. Even the US Air Force, with its surveillance radars at Dover

Air Force Base, was unable to identify the miscreant.

The incident was not isolated. A rudimentary data search turns up a stream

of such incidents since the early 1990s, from Florida to Nebraska, Colorado

and California, with a similar pattern: a loud and inexplicable boom. The

phantom boomers appear to avoid densely populated areas, and the stories

usually go no further than the local paper. Only a few local papers have a

searchable website, so it is highly probable that only a minority of boom

events are reported outside the affected area.

The first conclusion from this data is that supersonic aircraft are

operating over US. Secondly, we may conclude that the USAF and other

services either cannot identify them, or that they are misleading the public

because the operations are secret.

The latter case is supported by the existence of a massive secret structure,

which can truly be described as a 'shadow military', and which

exists in

parallel with the programs that the Department of Defense (DoD) discloses in

public. It is protected by a security system of great complexity. Since

1995, two high-level commissions have reported on this system, and have

concluded that it is too complex; that it is immensely expensive, although

its exact costs defy measurement; that it includes systematic efforts to

confuse and disinform the public; and that in some cases it favors security

over military utility. The defense department, however, firmly resists any

attempt to reform this system.

As the Clinton administration begins its last year in office, it continues

to spend an unprecedented proportion of the Pentagon budget on 'black'

programs - that is, projects that are so highly classified they cannot be

identified in public. The total sums involved are relatively easy to

calculate. In the unclassified version of the Pentagon's budget books, some

budget lines are identified only by codenames. Other classified programs are

covered by vague collective descriptions, and the dollar numbers for those

line items are deleted. However, it is possible to estimate the total value

of those items by subtracting the unclassified items from the category

total.

In Financial Year 2001 (FY01), the

USAF plans to spend US$4.96 billion on

classified research and development programs. Because white-world R&D is

being cut back, this figure is planned to reach a record 39% of total USAF

R&D. It is larger than the entire army R&D budget and two-thirds the size of

the entire navy R&D budget. The USAF's US$7.4 billion budget for classified

procurement is more than a third of the service's total budget.

Rise and rise of SAP

Formally,

black projects within the DoD are known as unacknowledged

Special

Access Programs (SAPs). The Secretary or Deputy Secretary of Defense must

approve any DoD-related SAP at the top level of the defense department. All

SAPs are projects that the DoD leadership has decided cannot be adequately

protected by normal classification measures. SAPs implement a positive

system of security control in which only selected individuals have access to

critical information. The criteria for access to an SAP vary, and the

program manager has ultimate responsibility for the access rules, but the

limits are generally much tighter than those imposed by normal need-to-know

standards.

For example, a SAP manager may insist on lie-detector testing for anyone

who has access to the program. Another key difference between SAPs and

normal programs concerns management and oversight. SAPs report to the

services, and ultimately to the DoD and Congress, by special channels which

involve a minimum number of individuals and organizations. In particular,

the number of people with access to multiple SAPs is rigorously limited.

In 1997, according to the report of a Senate commission (the Senate

Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy), there were around

150 DoD-approved SAPs. These included SAPs initiated by the department and

its branches and those initiated by other agencies (for example, the Central

Intelligence Agency [CIA] or the Department of Energy [DOE]) in which the

DoD was

involved. SAPs are divided into three basic types:

Within each group

are two major classes - acknowledged and unacknowledged.

Some of the acknowledged SAPs - most of them - started as unacknowledged

programs. This is the case with the F-117 and B-2, and (on the operations

side) with army's 160th Special Operations Air Regiment (SOAR). The

existence of these programs is no longer a secret, but technical and

operational details are subject to strict, program-specific access rules.

An unacknowledged SAP - a black program - is a program which is considered

so sensitive that the fact of its existence is a 'core secret', defined in

USAF regulations as "any item, progress, strategy or element of information,

the compromise of which would result in unrecoverable failure". In other

words, revealing the existence of a black program would undermine its

military value.

The Joint Security Commission which was convened by then deputy Secretary of

Defense Bill Perry in 1993, and which reported in 1995, concluded that

SAPs

had been used extensively in the 1980s "as confidence in the traditional

classification system declined". By the time the report was published,

however, the DoD had taken steps to rationalize the process by which

SAPs

were created and overseen. Until 1994, each service had its own SAP office

or directorate, which had primary responsibility for its programs. The Perry

reforms downgraded these offices and assigned management of the SAPs to a

new organization at defense department level. This is based on three

directors of special programs, each of whom is responsible for one of the

three groups of SAPs - acquisition, operations and intelligence. They report

to the respective under-secretaries of defense (acquisition and technology,

policy and C4ISR).

The near-US$5 billion in black programs in the USAF research and development

budget are in the acquisition category. They are overseen within the DoD by

Maj Gen Marshal H Ward, who is director of special programs in the office of

Dr Jacques Gansler, under-secretary of defense for acquisition, technology

and logistics. Gen Ward heads an SAP Coordination Office and, along with his

counterparts in the policy and C4ISR offices, is part of an

SAP Oversight

Committee (SAPOC), chaired by the Deputy Secretary of Defense, John Hamre,

with Dr Gansler as vice-chair. The SAPOC is responsible for approving new

SAPs and changing their status; receiving reports on their status; and,

among other things, making sure that SAPs do not overlap with each other.

This was a major criticism in the 1995 report: "If an acquisition

SAP is

unacknowledged," the commissioners remarked, "others working in the same

technology area may be unaware that another agency is developing a program.

The government may pay several times over for the same technology or

application developed under different special programs."

This problem was particularly prevalent in the case of stealth technology:

in the lawsuit over the A-12 Avenger II program, McDonnell Douglas and

General Dynamics charged that technology developed in other stealth programs

would have solved some of the problems that led to the project's

cancellation, but that the government did not supply it to the A-12 program.

Today, Gen Ward is the DoD-wide overseer for all stealth technology

programs. The SAPOC co-ordinates the reporting of SAPs to

Congress. Whether SAPs are acknowledged or not, they normally report to four Congressional

committees:

-

the House National Security Committee

-

the Senate Armed

Services Committee

-

the defense subcommittees of the House and Senate

Appropriations committees

Committee members and staffs are briefed in

closed, classified sessions.

However, there are several serious limitations to Congressional reporting of

SAPs. One of these is time. In the first quarter of 1999, the defense

subcommittee of the House Appropriations committee scheduled half a day of

hearings to review 150 very diverse SAPs. Another issue, related to time and

security, is that the reporting requirements for SAPs are rudimentary and

could technically be satisfied in a couple of pages.

A more substantial limitation on oversight is that some unacknowledged

SAPs

are not reported to the full committees. At the Secretary of Defense's

discretion, the reporting requirements may be waived. In this case, only

eight individuals - the chair and ranking minority member of each of the

four defense committees - are notified of the decision. According to the

1997 Senate Commission, this notification may be only oral. These "waived SAPs"

are the blackest of black programs.

How many of the SAPs are unacknowledged, and how many are waived, is a

question which only a few people can answer:

A final question is whether SAP reporting rules are followed all the time.

Last summer, the House Defense Appropriations Committee complained that "the

air force acquisition community continues to ignore and violate a wide range

of appropriations practices and acquisition rules". One of the alleged

infractions was the launch of an SAP without Congressional notification. In

their day-to-day operations, SAPs enjoy a special status. An

SAP manager has

wide latitude in granting or refusing access, and because their principal

reporting channel is to the appropriate DoD-level director of special

programs. Each service maintains an SAP Central Office within the office of

the service secretary, but its role is administrative - its primary task is

to support SAP requests by individual program offices - and its director is

not a senior officer.

Within the USAF, there are signs that SAPs form a 'shadow department'

alongside the white-world programs. So far, no USAF special program director

has gone on to command USAF Materiel Command (AFMC), AFMC's

Aeronautical

Systems Center (ASC), or their predecessor organizations. These positions

have been dominated by white-world logistics experts. On the other hand,

several of the vice-commanders in these organizations in the 1990s have

previously held SAP oversight assignments, pointing to an informal

convention under which the vice-commander, out of the public eye, deals with

highly sensitive programs. The separation of white and black programs is

further emphasized by arrangements known as 'carve-outs', which remove

classified programs from oversight by defense-wide security and

contract-oversight organizations.

Cover mechanisms

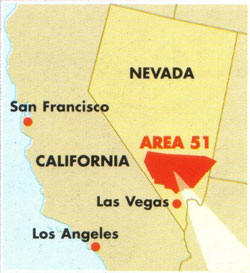

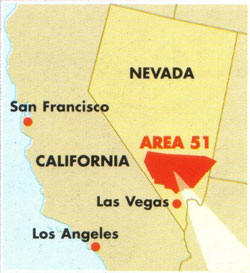

A similar parallel organization can be seen in the organization of the

USAF's flight-test activities. The USAF Flight Test Center (AFFTC) has a

main location at Edwards AFB, which supports most USAF flight-test programs.

Some classified programs are carried out at Edwards' North Base, but the

most secure and sensitive programs are the responsibility of an AFFTC

detachment based at the secret flight-test base on the edge of the dry

Groom

Lake, Nevada, and known as

Area 51. The USAF still refuses to identify the

Area 51 base, referring to it only as an 'operating location near

Groom

Lake'. It is protected from any further disclosure by an annually renewed

Presidential order (see Map).

Area 51's linkage to Edwards is a form of 'cover' - actions and statements

which are intended to conceal the existence of a black program by creating a

false impression in public. The 1995 Commission report concluded that cover

was being over-used. While conceding that cover might be required for

"potentially life-threatening, high-risk, covert operations", the report

stated baldly that "these techniques also have increasingly been used for

major acquisition and technology-based contracts to conceal the fact of the

existence of a facility or activity". The report added that "one military

service routinely uses cover mechanisms for its acquisition [SAPs], without

regard to individual threat or need".

Cover mechanisms used by the DoD have included the original identification

of the U-2 spyplane as a weather-research aircraft and the concealment of

the CIA's Lockheed A-12 spyplane behind its acknowledged cousins, the YF-12

and SR-71. Another example of cover is the way in which people who work at

Area 51 are nominally assigned to government or contractor organizations in

the Las Vegas area, and commute to the base in unmarked aircraft.

After the first wave of 'skyquake' incidents hit Southern California in

199192, and preliminary results from US Geological Service seismologists

suggested that they were caused by overflights of high-speed aircraft, the

USAF's Lincoln Laboratory analyzed the signatures from one boom event and

concluded that it was caused by navy fighter operations offshore. The

confirmed DoD use of cover makes it impossible to tell whether the

USAF

report is genuine or a cover story. The fact that cover is extensively used

to protect black programs adds weight to the theory that some white-world

projects may, in fact, be intended as cover. One example is the X-30

National Aerospaceplane (NASP) project, which was launched in 1986, cut back

in 1992 and terminated in 1994. In retrospect, the stated goal of NASP - to

develop a single-stage-to-orbit vehicle based on air-breathing scramjet

technology - seems ambitious and unrealistic.

Considered as a cover for a black-world hypersonic program, however, NASP

was ideal. NASP provided a credible reason for developing new technologies -

such as high-temperature materials and slush hydrogen - building and

improving large test facilities, and even setting up production facilities

for some materials. These activities would have been hard to conceal

directly, and would have pointed directly to a classified hypersonic program

without a cover story.

Vanishing project syndrome

Intentional cover is supported by two mechanisms, inherent in the structure

of unacknowledged SAPs, that result in the dissemination of plausible but

false data, or disinformation. Confronted with the unauthorized use of a

program name or a specific question, an 'accessed' individual may deny all

knowledge of a program - as he should, because its existence is a core

secret, and a mere "no comment" is tantamount to confirmation. The

questioner - who may not be aware that an accessed individual must respond

with a denial - will believe that denial and spread it further.

Also, people may honestly believe that there are no black programs in their

area of responsibility. For example, Gen George Sylvester, commander of

Aeronautical Systems Division in 1977, was not 'accessed' into the ASD-managed

Have Blue stealth program, even though he was nominally responsible for all USAF aircraft programs. Had he been asked whether

Have Blue existed, he

could have candidly and honestly denied it. Presented with a wall of denial,

and with no way to tell the difference between deliberate and fortuitous

disinformation, most of the media has abandoned any serious attempts to

investigate classified programs.

The process of establishing an SAP is, logically, covert. To make the

process faster and quieter, the DoD may authorize a Prospective SAP (P-SAP)

before the program is formally reviewed and funded: the P-SAP may continue

for up to six months. The P-SAP may account for the 'vanishing project

syndrome' in which a promising project simply disappears off the scope.

Possible examples include the ultra-short take-off and landing Advanced

Tactical Transport, mooted in the late 1980s; and the A/F-X long-range

stealth attack aircraft, ostensibly cancelled in 1993.

A further defense against disclosure is provided by a multi-level

nomenclature system. All DoD SAPs have an unclassified nickname, which is a

combination of two unclassified words such as Have Blue or

Rivet Joint.

Even in a

program that has a standard designation, the SAP nickname may be used on

badges and secured rooms to control access to information and physical

facilities.

A DoD SAP may also have a one-word classified codename. In this case, full

access to the project is controlled by the classified codename. The two-word

nickname, in this case, simply indicates that a program exists, for

budgetary, logistics or contractual purposes. The purpose, mission and

technology of the project are known only to those who have been briefed at

the codename level. Therefore, for example, Senior Citizen and Aurora could

be one and the same.

Both the 1995 and 1997 panels recommended substantial changes to the

classification system, starting with simplification and rationalization.

SAPs are not the only category of classification outside the

normal confidential/ secret/top secret system:

-

the intelligence

community classifies much of its product as Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI)

-

the Department of Energy uses Restricted Data (RD) and Critical Nuclear

Weapons Design Information (CNWDI).

The panels called for a simplified

system that would encompass SAPs, SCI and the

DoE standards.

Both commissions also accused the DoD and other agencies of protecting too

much material within special access boundaries, and doing so in an

inconsistent manner. As the 1995 report put it:

"Perhaps the greatest

weakness in the entire system is that critical specially protected

information within the various compartments is not clearly identified."

One general told the commission that an

SAP was like

"trying to protect

every blade of grass on a baseball field. He had to have a hundred players

to guard the entire field, when only four persons to protect home plate

would suffice."

Different services used different standards to determine how and when to

establish SAPs, according to the 1995 commission. In one case, two services

and the DoE were running concurrent programs with the same technology. One

military service classified its program as Top Secret Special Access and

protected it with armed guards. The other military service classified its

program as Secret Special Access with little more than tight need-to-know

protection applied. The DoE classified its program as Secret, adopting

discretionary need-to-know procedures. "This problem is not uncommon", the

report remarked.

The commission gave up on efforts to measure the direct costs of security,

saying that "no one has a good handle on what security really costs". Direct

costs, the commission estimated, ranged from 1% to 3% of total operating

costs in an acknowledged SAP, and from 3% to 10% on a black project,

although one SAP program manager estimated security costs could be as high

as 40% of total operating costs. The commission found that there was no way

to estimate the indirect costs of security, such as the lost opportunities

to rationalize programs.

The 1995 commission also pointed out that the military utility of a

breakthrough technology is limited if commanders do not know how to use it.

A senior officer on the Joint Staff remarked that

"we still treat certain

capabilities as pearls too precious to wear - we acknowledge their value,

but because of their value, we lock them up and don't use them for fear of

losing them".

The report implied that the

SAP world keeps field commanders

in the dark until the systems are ready for use and even then,

"they are put

under such tight constraints that they are unable to use [SAP products] in

any practical way".

Risk management

Both the DoD's

own commission and the later Senate commission pushed for a

simpler system, with more consistent rules, and based on the principle of

risk management: that is, focusing security efforts to protect the

information that is most likely to be targeted and would be most damaging if

compromised.

Since 1995, the US Government has declassified some programs. Northrop's

Tacit Blue, a prototype for a battlefield surveillance aircraft, was

unveiled in 1996, but it had made its last flight in 1985 and had not led to

an operational aircraft. The USAF publicly announced the acquisition of

MiG-29s from Moldova in 1998 - however, the previous history of the 4477th

Test and Evaluation Squadron, which has flown Soviet combat aircraft from

Area 51 since the 1970s, remains classified.

Some recent programs appear to combine an unclassified and a SAP element.

One example is the Boeing X-36 unmanned test aircraft. The X-36 itself was

disclosed in March 1996, when it was nearly complete: at the time, it was a

McDonnell Douglas project, and it clearly resembled the company's proposed

Joint Strike Fighter design. However, it was also a subscale test vehicle

for an agile, very-low-observables combat aircraft, incorporating a

still-classified thrust vectoring system with an externally fixed nozzle.

The nozzle itself remains classified, and it is likely that a full-scale

radar cross-section model of the design was also built under a secret

program.

Another hybrid is the USAF's Space Maneuver Vehicle (SMV), originated by

Rockwell but a Boeing project. This appears to have been black before 1997,

with the designation X-40. (The USAF has reserved the designations X-39 to

X-42 for a variety of programs.) A subscale, low-speed test vehicle was

revealed in that year; it was described as the Miniature Spaceplane

Technology (MiST) demonstrator and was designated X-40A, a suffix that

usually indicates the second derivative of an X-aircraft. Late last year,

Boeing was selected to develop a larger SMV test vehicle under

NASA's

Future-X program - this effort is unclassified, and is designated X-37. The

question is whether the USAF is still quietly working on a full-scale X-40

to explore some of the SMV's military applications, including space control

and reconnaissance.

Another indication of greater openness is the fact that the three

reconnaissance unmanned air vehicle (UAV) programs launched in 199495 - the

Predator, DarkStar and Global Hawk - were unclassified. The General Atomics

Gnat 750, which preceded the Predator, was placed in service under a CIA

black program, and the DarkStar and Global Hawk, between them, were designed

as a substitute for a very large, long-endurance stealth reconnaissance UAV

developed by Boeing and Lockheed and cancelled in 1993. However, the budget

numbers indicate that unacknowledged SAPs are very much alive. Neither has

the DoD taken any drastic steps to rationalize the security system. Recent

revelations over the loss of data from DoE laboratories have placed both

Congress and Administration in a defensive posture, and early reform is

unlikely.

A telling indication of the state of declassification, however, was the

release in 1998 of the CIA's official history of the U-2 program. It is

censored to remove any mention of the location of the program. However, an

earlier account of the U-2 program, prepared with the full co-operation of

Lockheed and screened for security, includes a photo of the Area 51 ramp

area. It shows hangars that can still be located on overhead and

ground-to-ground shots of the base, together with terrain that can be

correlated with ridgelines in the

Groom Lake area. A telling indication of the state of declassification, however, was the

release in 1998 of the CIA's official history of the U-2 program. It is

censored to remove any mention of the location of the program. However, an

earlier account of the U-2 program, prepared with the full co-operation of

Lockheed and screened for security, includes a photo of the Area 51 ramp

area. It shows hangars that can still be located on overhead and

ground-to-ground shots of the base, together with terrain that can be

correlated with ridgelines in the

Groom Lake area.

However, the DoD has opposed legislation - along the lines of the 1997

Senate report - that would simplify the current system and create an

independent authority to govern declassification.

In the summer of 1999, Deputy Defense Secretary John Hamre said that the

DoD

was opposed to the entire concept of writing all security policies into law,

because it would make the system less flexible. The DoD is also against the

idea of a "balance of public interest" test for classification. Another

major concern was that an independent oversight office would be cognizant of

all SAPs.

Hans Mark, director for defense research and engineering, defended the

current level of SAP activity in his confirmation hearing in June 1998.

SAPs, Mark said, "enable the DoD to accomplish very sensitive, high payoff

acquisition, intelligence, and operational activities". Without them, he

said, "many of these activities would not be possible, and the effectiveness

of the operational forces would be reduced as a result. I am convinced that

special access controls are critical to the success of such highly sensitive

activities."

Industry's role

Not only have

SAPs held their ground, but their philosophy has also spread

to other programs and agencies. NASA's 'faster, better, cheaper' approach to

technology demonstration and space exploration has been brought to the

agency by its administrator, Dan Goldin, who was previously involved with

SAPs with TRW. The Advanced Concept Technology Demonstration (ACTD) programs

conducted by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) are also

based on similar principles to SAPs. In some cases - such as Frontier

Systems' A160 long-endurance helicopter demonstrator - DARPA contractors are

providing effective security outside a formal SAP framework.

SAPs are visible in the prosperity of special-program organizations within

industry. Boeing's Phantom Works, founded in 1992 on the basis of existing

black program work at McDonnell Douglas but with an added emphasis on

low-cost prototyping, has been expanded by the new Boeing to include

facilities and people at Palmdale and Seattle. While the headquarters of the

Phantom Works is being moved to Seattle, this move directly affects only a

small staff, and the St Louis operation still appears to be active. Its main

white-world program has been the construction of the forward fuselages of

the X-32 prototypes, but this only occupies one of many secure hangar bays.

The X-32 prototypes are being assembled at Palmdale, in a hangar divided by

a high curtain. Another test vehicle is being assembled in the same hangar,

behind a high curtain, and background music plays constantly to drown out

any telltale conversations.

In the early 1980s, Boeing expanded its military-aircraft activities and

built large new facilities - including an engineering building and indoor RCS range at Boeing Field - which were specifically designed to support

SAPs, with numerous, physically separate 'vaults' to isolate secure programs

from each other. Boeing's black-projects team at Seattle is considered to be

one of the best in the industry.

Lockheed Martin's Skunk Works has changed in character since the 1970s. The

original Advanced Development Projects (ADP) unit was built around a core

group of engineering leaders, who would tap people and resources from the

'white-world' Lockheed-California company when they were needed. In the

1980s, the Skunk Works grew in size and importance, while

Lockheed-California diminished. Today, the Skunk Works is a large,

stand-alone organization with 4,000-plus employees. As far as the world

knows, its output in the past 10 years comprises two YF-22 prototypes, parts

of two DarkStar prototypes, the X-33 RLV and the two X-35 JSF demonstrators.

In mid-1999, Lockheed Martin disclosed that a new advanced-technology

organization had been set up within the Skunk Works, headed by veteran

engineer Ed Glasgow, to explore the potential or revolutionary technologies.

In the unclassified realm, these include a hybrid heavy-lift vehicle

combining lighter-than-air and aerodynamic principles, and a

supersonic-cruise vehicle with design features that virtually eliminate a

sonic boom signature on the ground.

The Skunk Works' renown has overshadowed another Lockheed Martin

organization with a long-standing connection with SAPs, located within

Lockheed Martin Tactical Aircraft Systems (LMTAS) at Fort Worth. This group

has existed since the late 1950s, when General Dynamics sought

special-programs work to keep its engineering workforce together between

major projects. Notable projects include Kingfish, which was the

ramjet-powered rival to Lockheed's A-12 Blackbird and continued in

development into the early 1960s, and the RB-57F, a drastically modified

Canberra designed for high-altitude reconnaissance missions.

Big safari

More recently, the group worked on early stealth concepts - including the

design which led to the Navy's A-12 Avenger II attack aircraft - and has

modified transport-type aircraft for sensitive reconnaissance missions under

the USAF's Big Safari program.

Northrop Grumman's major involvement in manned-aircraft SAPs may be winding

down as the Pico Rivera plant - which housed the B-2 program - is closed

down and its workforce disperses. However, the company's acquisitions in

1999, including Teledyne Ryan Aeronautical (TRA) and California Microwave,

indicate that it will remain a force in UAV programs, including SAPs. TRA

has a long association with SAPs and SAP-like programs, dating back to

Vietnam-era reconnaissance UAVs and the AQM-91 Firefly high-altitude,

low-observable reconnaissance drone tested in the early 1970s.

Raytheon has acquired important SAP operations through acquisitions. The

former Hughes missile operation was presumably involved in the classified

air-breathing AMRAAM variant that was apparently used in Operation 'Desert

Storm', and in subsequent extended-range air-to-air missile programs. Texas

Instruments developed the ASQ-213 HARM Targeting System pod under a black

program between 1991 and 1993, when it was unveiled. (HTS was a classic

example of a 'vanishing' program: briefly mentioned in early 1990, it turned

black shortly afterwards.) The former E-Systems has been heavily involved in

intelligence programs since its formation.

Next stealth

One likely strategic goal of current

SAPs is the pursuit of what one senior

engineer calls "the next stealth" - breakthrough technologies that provide a

significant military advantage. Examples could include high-speed technology

- permitting reconnaissance and strike aircraft to cruise above M45 - and

visual and acoustic stealth measures, which could re-open the airspace below

15,000ft (4,600m) to manned and unmanned aircraft.

The existence of high-supersonic aircraft projects has been inferred from

sighting reports, the repeated, unexplained sonic booms over the US and

elsewhere, the abrupt retirement of the SR-71 and from the focus of

white-world programs, such as NASP and follow-on research efforts such as

the USAF's HyTech program. The latter have consistently been aimed at

gathering data on speeds in the true hypersonic realm - well above M6, where

subsonic-combustion ramjets give way to supersonic-combustion ramjets

(scramjets) - implying that speeds from M3 to M6 present no major unsolved

challenges.

One researcher in high-speed technology has confirmed to IDR that he has

seen what appear to be photographs of an unidentified high-speed aircraft,

obtained by a US publication. In a recent sighting at Area 51, a group of

observers claim to have seen a highly blended slender-delta aircraft which

closely resembles the aircraft seen over the North Sea in August 1999.

Visual stealth measures were part of the original Have Blue program, and one

prototype was to have been fitted with a counter-illumination system to

reduce its detectability against a brightly lit sky. However, both

prototypes were lost before either could be fitted with such a system. More

recent work has focused on electrochromic materials - flat panels which can

change color or tint when subjected to an electrical charge - and Lockheed

Martin Skunk Works is known to have co-operated with the DoE's Lawrence

Berkeley Laboratory on such materials.

Yet, the plain fact is that the public and the defense community at large

have little idea of what has been achieved in unacknowledged SAPs since the

early 1980s. Tacit Blue, the most recently declassified product of the

black-aircraft world, actually traces its roots to the Ford Administration.

If nothing else, the dearth of hard information since that time, shows that

the SAP system - expensive, unwieldy and sometimes irrational as it might

seem - keeps its secrets well. Whatever rattled the dinner tables of

Delaware a year ago may remain in the shadows for many years.

'The government may pay several times over for the same technology or

application developed under different special programs'

'Presented with a wall of denial, most of the media has abandoned any

serious attempts to investigate classified programs'

-

In the late 1980s, this large hangar with an uninterrupted opening around

60m wide and over 20m high was constructed at

Area 51, the USAF's secret

flight test center at Groom Lake, Nevada. The

project that it was built to house remains secret.

(click right image to enlarge) In the late 1980s, this large hangar with an uninterrupted opening around

60m wide and over 20m high was constructed at

Area 51, the USAF's secret

flight test center at Groom Lake, Nevada. The

project that it was built to house remains secret.

(click right image to enlarge)

-

The threat of armed force is used routinely to protect classified programs.

Area 51 is defended by a force of armed security personnel who

work for a civilian contractor and by helicopter patrols, and the eastern

border of the site is ringed with electronic sensors.

(click left image to enlarge) The threat of armed force is used routinely to protect classified programs.

Area 51 is defended by a force of armed security personnel who

work for a civilian contractor and by helicopter patrols, and the eastern

border of the site is ringed with electronic sensors.

(click left image to enlarge)

-

Northrop's

Tacit Blue, an experimental low-observable aircraft designed to

carry a Hughes battlefield-surveillance radar, was tested at

Area 51 in

1982-85 and unveiled in 1996. Although the program originated under the

Ford

Administration, it is the most recent classified manned-aircraft

program to have been disclosed. Northrop's

Tacit Blue, an experimental low-observable aircraft designed to

carry a Hughes battlefield-surveillance radar, was tested at

Area 51 in

1982-85 and unveiled in 1996. Although the program originated under the

Ford

Administration, it is the most recent classified manned-aircraft

program to have been disclosed.

-

The

Boeing X-36 unmanned prototype started as a Special Access

Program and was partly declassified in 1996 so that McDonnell Douglas could

use its technology in its Joint Strike Fighter proposal. Some aspects of its

design including its use of stealth technology and its thrust-vectoring

exhaust remain classified. The

Boeing X-36 unmanned prototype started as a Special Access

Program and was partly declassified in 1996 so that McDonnell Douglas could

use its technology in its Joint Strike Fighter proposal. Some aspects of its

design including its use of stealth technology and its thrust-vectoring

exhaust remain classified.

-

Shoulder patch from the

4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES), the

covert USAF unit which has tested numerous Soviet aircraft at

Area 51. Shoulder patch from the

4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES), the

covert USAF unit which has tested numerous Soviet aircraft at

Area 51.

-

Boeing's X-37 spaceplane, being developed for

NASA, was originally designed

by Rockwell and supported by the USAF as a

special access program. The designation X-40 applies to its military

variants. Boeing's X-37 spaceplane, being developed for

NASA, was originally designed

by Rockwell and supported by the USAF as a

special access program. The designation X-40 applies to its military

variants.

-

The now-cancelled Lockheed Martin/ Boeing

DarkStar may have been a

scaled-down version of a large, long-endurance stealth reconnaissance UAV

which was cancelled in 1993 after at least $1 billion had been spent on its

development. The now-cancelled Lockheed Martin/ Boeing

DarkStar may have been a

scaled-down version of a large, long-endurance stealth reconnaissance UAV

which was cancelled in 1993 after at least $1 billion had been spent on its

development.

-

The Lockheed

YF-12C reconnaissance aircraft was disclosed

before its first flight, but its testing and operation was used to mask the

existence of its covert precursor, the CIA's A-12. The latter was not

disclosed until 1982, 14 years after its retirement. The Lockheed

YF-12C reconnaissance aircraft was disclosed

before its first flight, but its testing and operation was used to mask the

existence of its covert precursor, the CIA's A-12. The latter was not

disclosed until 1982, 14 years after its retirement.

-

The Soviet Union was presumably aware of the location of

Area 51 by the

early 1960s, when its first reconnaissance satellites began to survey the

United States. However, the Pentagon continues to avoid acknowledging its

existence.

(click right image to

enlarge) The Soviet Union was presumably aware of the location of

Area 51 by the

early 1960s, when its first reconnaissance satellites began to survey the

United States. However, the Pentagon continues to avoid acknowledging its

existence.

(click right image to

enlarge)

|

A telling indication of the state of declassification, however, was the

release in 1998 of the CIA's official history of the U-2 program. It is

censored to remove any mention of the location of the program. However, an

earlier account of the U-2 program, prepared with the full co-operation of

Lockheed and screened for security, includes a photo of the Area 51 ramp

area. It shows hangars that can still be located on overhead and

ground-to-ground shots of the base, together with terrain that can be

correlated with ridgelines in the

A telling indication of the state of declassification, however, was the

release in 1998 of the CIA's official history of the U-2 program. It is

censored to remove any mention of the location of the program. However, an

earlier account of the U-2 program, prepared with the full co-operation of

Lockheed and screened for security, includes a photo of the Area 51 ramp

area. It shows hangars that can still be located on overhead and

ground-to-ground shots of the base, together with terrain that can be

correlated with ridgelines in the

Northrop's

Tacit Blue, an experimental low-observable aircraft designed to

carry a Hughes battlefield-surveillance radar, was tested at

Northrop's

Tacit Blue, an experimental low-observable aircraft designed to

carry a Hughes battlefield-surveillance radar, was tested at

The

Boeing X-36 unmanned prototype started as a Special Access

Program and was partly declassified in 1996 so that McDonnell Douglas could

use its technology in its Joint Strike Fighter proposal. Some aspects of its

design including its use of stealth technology and its thrust-vectoring

exhaust remain classified.

The

Boeing X-36 unmanned prototype started as a Special Access

Program and was partly declassified in 1996 so that McDonnell Douglas could

use its technology in its Joint Strike Fighter proposal. Some aspects of its

design including its use of stealth technology and its thrust-vectoring

exhaust remain classified. Shoulder patch from the

4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES), the

covert USAF unit which has tested numerous Soviet aircraft at

Shoulder patch from the

4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES), the

covert USAF unit which has tested numerous Soviet aircraft at

Boeing's X-37 spaceplane, being developed for

NASA, was originally designed

by Rockwell and supported by the USAF as a

special access program. The designation X-40 applies to its military

variants.

Boeing's X-37 spaceplane, being developed for

NASA, was originally designed

by Rockwell and supported by the USAF as a

special access program. The designation X-40 applies to its military

variants.  The now-cancelled Lockheed Martin/ Boeing

DarkStar may have been a

scaled-down version of a large, long-endurance stealth reconnaissance UAV

which was cancelled in 1993 after at least $1 billion had been spent on its

development.

The now-cancelled Lockheed Martin/ Boeing

DarkStar may have been a

scaled-down version of a large, long-endurance stealth reconnaissance UAV

which was cancelled in 1993 after at least $1 billion had been spent on its

development.  The Lockheed

YF-12C reconnaissance aircraft was disclosed

before its first flight, but its testing and operation was used to mask the

existence of its covert precursor, the CIA's A-12. The latter was not

disclosed until 1982, 14 years after its retirement.

The Lockheed

YF-12C reconnaissance aircraft was disclosed

before its first flight, but its testing and operation was used to mask the

existence of its covert precursor, the CIA's A-12. The latter was not

disclosed until 1982, 14 years after its retirement.