|

by MacGregor Campbell

10 June 2009

from

NewScientist Website

Observers using the

Anglo-Australian Telescope took this series of 1-second exposures,

each snapped

0.6-seconds apart, around the predicted time of impact.

A bright flash can be

seen in the second image (centre of frame), and faintly in the third

and fourth as well

(Image: Jeremy

Bailey/University of New South Wales/Steve Lee/Anglo-Australian

Observatory)

Japan's

Kaguya lunar orbiter will end its

nearly two-year mission when it collides with the moon at 18:25 GMT

on Wednesday.

Observers in Asia and Australia may be

able to spot a bright flash or plume of dust from the crash, and

researchers will study its impact site to watch how radiation and

micrometeoroids weather the newly exposed lunar soil over time.

Launched in September 2007, Kaguya,

formerly known at SELENE, sought to shed light on the

formation and evolution of the moon by studying its composition,

gravitational field and surface characteristics.

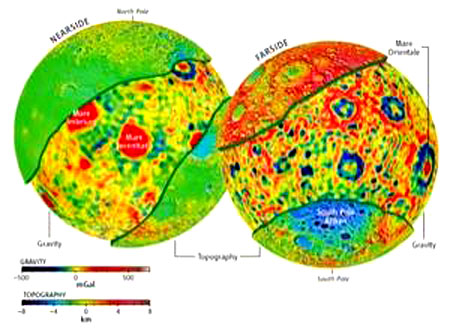

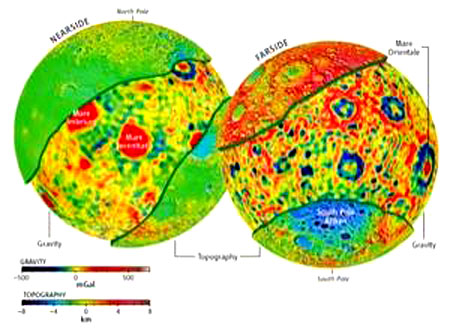

Kaguya

deployed two smaller satellites

after reaching lunar orbit that allowed it to relay data to Earth

while it was on the moon's far side and to better measure anomalies

in the moon's gravitational field (see

First gravity map of moon's far side unveiled).

The Japanese probe

Kaguya has created the first map of gravity differences on the far

side of the Moon,

which always points

away from Earth.

The gravity

signatures of some craters suggests the far side might have been

stiffer and cooler than expected

(Illustration: Namiki

et al/AAAS)

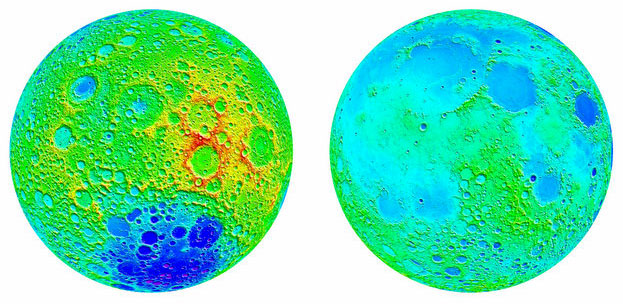

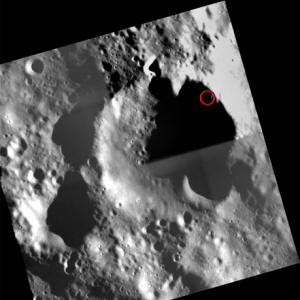

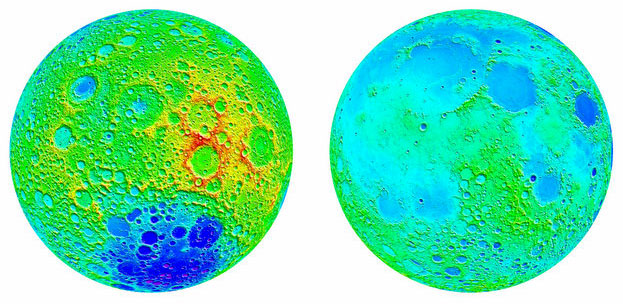

The topography maps

and free-air gravity maps of the global Moon obtained by KAGUYA.

The far-side is on

the left and the near-side is on the right.

Touch the topography map with your mouse or pointer. Then the

gravity map will show up.

It also made the world's first HD video

of the lunar surface (below video).

Like previous lunar orbiters, including China's

Chang'e 1 and Europe's

SMART-1 probes, Kaguya will end its

voyage in a violent rendezvous with the moon's surface.

JAXA/KAGUYA Earth-Rise and Earth-Set image

over the moon

by

NnoxS3

November 13, 2007

from

YouTube Website

Heat and light

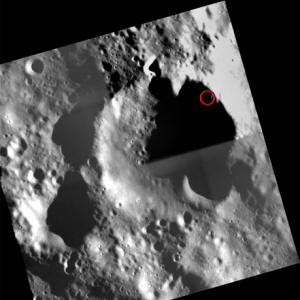

It is set to impact in the lower-right section of the moon's near

side (see images at top). Coming in at a very shallow angle – nearly

parallel to the ground – the probe has a high chance of skipping

across the surface, like a stone across a pond.

Ground-based observers are unlikely to see this skipping. But those

in Asia and Australia might be able to spot a plume of dust raised

by the impact, if it is backlit by the sun, like snow thrown up by a

skier ploughing through powder, says Bernard Foing, project

scientist of the European Space Agency's SMART-1 probe, which

impacted the moon in 2006.

Viewers may also see a brief flash as some of the kinetic energy of

the probe, which will be moving at 6000 kilometers per hour, is

converted to heat and light in the collision.

"It's a final show for

the Japanese people," says Shin-ichi Sobue, a researcher and

spokesperson for the Kaguya mission.

Foing says researchers can learn from these crashes.

"Impact is the

destiny of each orbiter," he told New Scientist. "We try to make use

of it as a research opportunity."

Space weathering

Peter Schultz, an expert on lunar impacts at Brown University in

Providence, Rhode Island, agrees. Depending on the specific terrain

of the impact site, the crash could leave an elongated scar,

exposing fresh soil, or regolith, to the harsh environment of space.

Scientists could watch how the lunar soil weathers over time under

solar radiation and bombardment by smaller meteoroids.

It would be

like "watching a wound heal", according to Schultz.

After the crash, attention will turn to

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance

Orbiter (LRO) and Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS)

missions, set to launch a week after Kaguya's demise.

LRO will orbit the moon, studying its composition and topography and

searching for possible sites for future human bases, while LCROSS

will bombard one of the moon's polar craters with two heavy

impactors in search of water ice there.

|