|

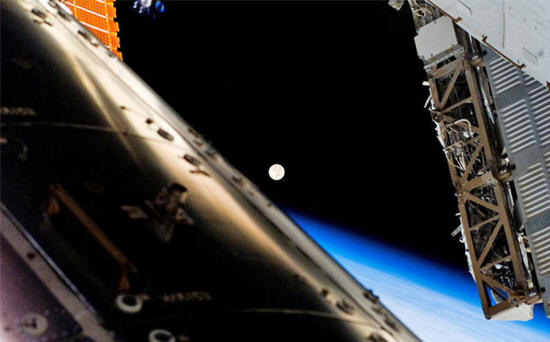

by Elizabeth Gibney the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

Space agencies are planning a Deep Space Gateway to orbit the Moon.

NASA and the European

Space Agency (ESA)

are hosting meetings to discuss the science plans, the first of

which are taking place on 5-6 December in Noordwijk, the

Netherlands.

Scientists are already jockeying for room on the platform.

James Carpenter is the human and robotic exploration strategy officer at ESA in Noordwijk, who organized the event and had to double the capacity of the agency's event to 250 people, owing to the level of interest.

Known as the Deep Space Gateway, the platform is the "commonly accepted" next step once the International Space Station retires in the mid-2020s, says David Parker, director of human spaceflight and robotic exploration at ESA.

The space agencies have made clear that its main purpose would be to test, from Earth's backyard, the technology for deep-space exploration and long-duration missions - including, eventually, going to Mars.

Doing so could help the project to avoid the fate of the International Space Station, which some have criticized for being slow to live up to its research potential.

But researchers should remember that the main purpose of both facilities is to support future exploration, says Richard Binzel, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge.

Still, researchers have already devised a vast array of experiments.

The platform's location - outside Earth's protective magnetic field and so representative of deep space, and with ready access to the Moon - would provide a unique environment for research, as well as testing how space affects human physiology and technology for survival.

Researchers will propose

ways in which the station could support planetary studies and allow

for innovative physics and astronomy experiments, says Carpenter.

These include a meteoroid-environment monitor, which would study the drifting interstellar dust that never reaches Earth owing to the planet's magnetic field.

A low-frequency radio

observatory could be used to pick up radiation from the Universe's

'dark ages', between 400,000 and 100 million years after

the Big Bang - which is hugely

challenging on Earth because of interference from human sources and

the planet's ionosphere, says Mark Bentum, a physicist at the

University of Twente in Enschede, the Netherlands.

Water has been confirmed on the Moon in the past decade, but researchers still know little about where it is, how much there is and how feasible it would be to extract.

Researchers aboard an

orbiting laboratory would also be able to control lunar rovers in

real time, and could study moon rock without having to return

samples to Earth.

Armin G÷lzhńuser, a physical chemist at Bielefeld University in Germany, wants to test the potential of nanometer-thick carbon membranes, made from fused aromatic molecules, for use as long-lasting, thin and efficient filters that could recycle wastewater or air.

Meanwhile, biochemist

Katharina Brinkert at the California Institute of Technology in

Pasadena and her colleagues have designed a device to boost the

solar-assisted production of hydrogen and oxygen, optimized for use

in microgravity.

In September, NASA signed a joint agreement with Roscosmos, its Russian counterpart, which outlined such a platform as part of their,

The Japanese and Canadian space agencies have also expressed interest.

Both NASA and ESA have already contracted industry partners to undertake preliminary work. But if and when the project moves forward will depend largely on NASA's new administrator.

James Bridenstine, a Republican member of the US Congress from Oklahoma, has been nominated for the role but has yet to be appointed.

If the Deep Space Gateway

is to launch as planned in the mid-2020s, key decisions need to be

made by the end of 2019, says Parker.

|