|

by Liverpool Hope University

February 06,

2020

from PHYS

Website

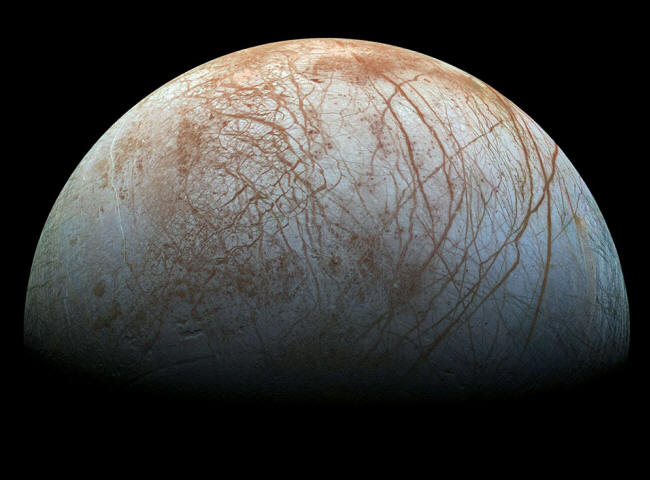

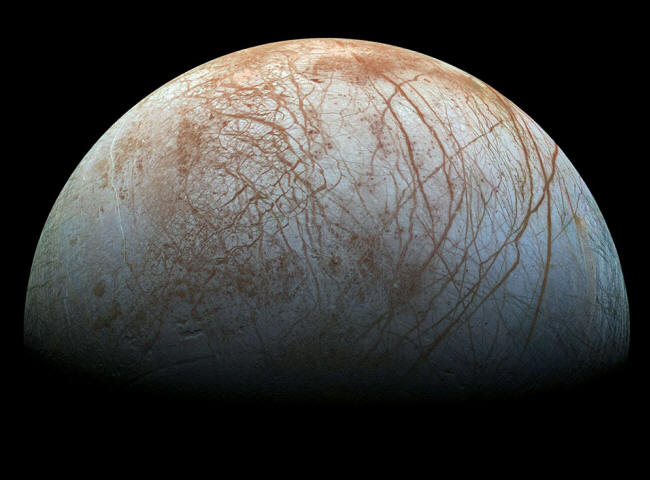

Credit: NASA

It's 'almost a racing certainty' there's alien life on

Jupiter's moon Europa - and Mars

could be hiding primitive microorganisms, too.

That's the view of leading British space scientist Professor

Monica Grady, who says the notion of undiscovered life in our

galaxy isn't nearly as far-fetched as we might expect.

Professor Grady, a Professor of Planetary and Space Science,

says the frigid seas beneath Europa's ice sheets could harbor

'octopus' like creatures.

Meanwhile the deep caverns and caves found

on

Mars may also hide subterranean life-forms - as they

offer shelter from intense solar radiation while also potentially

boasting remnants of ice.

Professor Grady was speaking at Liverpool Hope University,

where she's just been installed as Chancellor, and revealed:

"When it comes to the

prospects of

life beyond Earth, it's almost

a racing certainty that there's life beneath the ice on Europa.

"Elsewhere, if there's going to be life on Mars, it's going to

be under the surface of the planet.

"There you're protected from solar radiation. And that means

there's the possibility of ice remaining in the pores of the

rocks, which could act as a source of water.

"If there is something on Mars, it's likely to be very small -

bacteria.

"But I think we've got a better chance of having slightly higher

forms of life on Europa, perhaps similar to the intelligence of

an octopus."

Professor Grady isn't the

first to pinpoint Europa as a potential source of

extraterrestrial life.

And

the Moon - located more than 390 million miles from Earth

- has long been the subject of science fiction, too.

Europa, one of Jupiter's 79

known moons, is covered by a layer of ice up to 15 miles deep -

and there's likely liquid water beneath where life could dwell.

The ice acts as a protective barrier against both solar radiation

and asteroid impact.

Meanwhile, the prospect of hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor -

as well sodium chloride in Europa's salty water - also boost the

prospects of life.

As for what's beyond the Milky Way, Professor Grady says the

environmental conditions that led to life on Earth are 'highly

likely' to be replicated elsewhere.

The expert, resident at the Open University and who's also

worked with the European Space Agency (ESA),

adds:

"Our solar system is

not a particularly special planetary system, as far as we know,

and we still haven't explored all the stars in the galaxy.

"But I think it's highly likely there will be life elsewhere -

and I think it's highly likely they'll be made of the same

elements.

"Humans evolved from little furry mammals that got the

opportunity to evolve because the dinosaurs were killed by an

asteroid impact.

"That is probably not going to happen on every planet - but it's

at least possible based purely on a statistical argument.

"Whether we will ever be able to contact extraterrestrial life

is anyone's guess, purely because the distances are just too

huge.

"And as for so-called alien 'signals' received from space,

there's been nothing real or credible, I'm afraid."

In summer this year, at

least three separate missions will be launched to Mars.

The

ExoMars 2020, which launches in

July, is a joint project from the European Space Agency (ESA)

and the Russian space agency,

Roscosmos.

The Mars 2020 mission is NASA's new rover, planned to

touch-down on

the Red Planet in February 2021.

Meanwhile the

Hope Mars Mission is a planned

space exploration probe, funded by the United Arab Emirates, which

is set to launch in the summer.

And Professor Grady says it's not just Martian 'viruses' being

brought back to Earth that are a concern, the prospect of us

contaminating the planet with our own bugs is also paramount.

Prof. Grady - a member of the

Euro-Cares project designed to

curate samples returned from missions to asteroids, Mars, the Moon

and comets - reveals:

"Space agencies from

across the world are working to eventually send humans to Mars.

"But if you want to do that you need to at least have a jolly

good shot of bringing them back again. And so one of the big

steps in that process is actually to bring a rock back from

Mars.

"The NASA mission will collect samples in tubes and leave them

on the surface of Mars.

"And then, in 2026, ESA will send another mission to Mars to

collect those samples and put them in orbit around the red

planet.

"Then, another spacecraft will come and collect that capsule.

"It's about breaking the chain of contact between Mars and the

Earth, just in case we bring back some horrendous new virus.

"But we also don't want to contaminate Mars with our own

terrestrial bugs.

"And the tricky part will come when we prepare to send the first

people to Mars. Currently, we boil all the equipment in acid, or

we heat it to very high temperatures, before we send it off.

"But humans are, shall we say, a bit resistant to those

treatments!

"All of these protocols for sterilization have still got to be

determined."

Meanwhile Professor Grady

says that by looking at the bigger, inter-planetary picture, Earth's

own ecological situation is brought into sharp focus.

She says:

"We could be all

there is in the galaxy. And if there's only us, then we have a

duty to protect the planet.

"I'm fairly certain we're all there is at our level of

intelligence in this planetary system.

"And even if there are octopuses

on Europa, that doesn't give us

a reason to destroy our planet."

Professor Grady has also

been looking at the bigger picture by focusing on the minutiae - a

single grain of rock, the size of a full stop.

This speck was brought to Earth in 2010 by the Japanese "Hayabusa'

mission - where a robotic spacecraft was sent to the

near-Earth asteroid '25143

Itokawa' in order to collect a sample.

By analyzing this 'world in a grain of sand,' she hopes to unlock

mysteries of the universe.

She adds:

"When we look at this

grain, we can see that most of it is made up of silicates, but

it's also got little patches of carbon in it - and that carbon

is extra-terrestrial, because it also contains nitrogen and

hydrogen, which is not a terrestrial signature.

"In this one sample, a few microns in size, we can see that it's

been hit by other bits of meteorite, asteroid, and interstellar

dust.

"And with modern equipment you can start to untangle, not just a

grain, but the little bits inside this tiny grain.

"It's giving us an idea of how complex the record of

extra-terrestrial material really is.

"It also tells us the importance of analyzing the tiny things

when it comes to the bigger picture."

|