|

by Stephen Smith

May 28, 2010

from

Thunderbolts Website

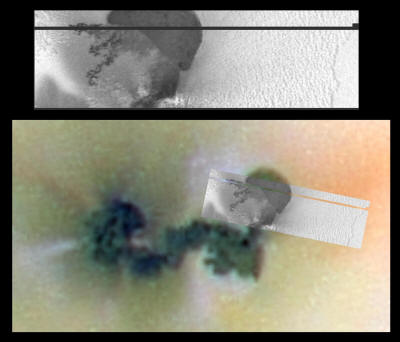

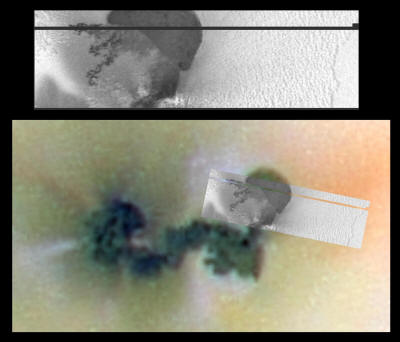

Plasma streamers

connect Jupiter with its moon Io.

Io has puzzled planetary scientists for

years. Electric Universe advocates are not so mystified.

The

Galileo spacecraft was launched

October 18, 1989 aboard the Atlantis space shuttle. Just as the

Cassini mission's images and data

analysis are providing substantial evidence for the Electric

Universe hypothesis, Galileo performed the same service while

exploring Jupiter and its family of 63 known satellites.

Galileo's power supply consisted of twin Plutonium-238 reactors that

used the heat from radioactive decay to power its instruments.

On September 21, 2003 the spacecraft was

incinerated when it was deliberately sent into Jupiter's vast

maelstrom so that it would not contaminate any of the moons,

especially Europa.

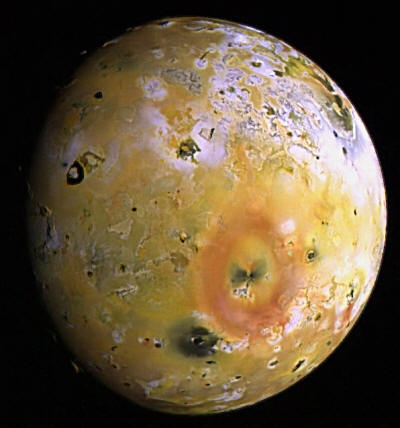

Since the two Voyager space probes discovered "surprising volcanic

activity" on Io, plasma physicist

Wal Thornhill

predicted that the plumes erupting from the so-called

"volcanic vents" would be hotter than any lava fields ever measured.

His prediction was confirmed when it was found that the "caldera"

around the vents exceeded temperatures of 2000 Celsius.

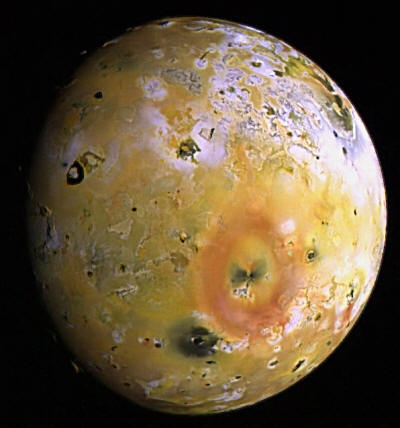

Io orbits close in to Jupiter, so intense electromagnetic radiation

bombards its surface, removing approximately one ton per second in

gases and other materials. Io acts like an electrical generator as

it travels through Jupiter’s plasmasphere, inducing over 400,000

volts across its diameter at more than three million amperes. That

tremendous current flows across its magnetic field into the electric

environment of Jupiter.

The plumes seen erupting from Io are the result of cathode arcs,

electrically etching the surface and blasting sulfur dioxide "snow"

up to 150 kilometers into space.

As Thornhill predicted, the most active regions of electric

discharge were found to be along the edges of so-called "lava

lakes,” while the remainder of the dark umbras surrounding them were

extremely cold.

No volcanic vents were found. Instead,

what was discovered is that the plumes move across Io, as

illustrated by the Prometheus (below image) hot spot that moved more

than 80 kilometers since it was first imaged by Voyager 2.

Galileo mission specialists were shocked

when they realized that the volcanic plumes also emit ultraviolet

light, characteristic of electric arcs.

Electric discharges can accelerate material to high velocity,

producing uniform trajectories that then deposit it at a uniform

distance.

This explains why there are rings around

the various caldera. Cathode erosion of Io also provides a reason

why the plumes seen highlighted against the black of space possess a

filamentary structure, reminiscent of

Birkeland currents that have been

discussed many times in these pages.

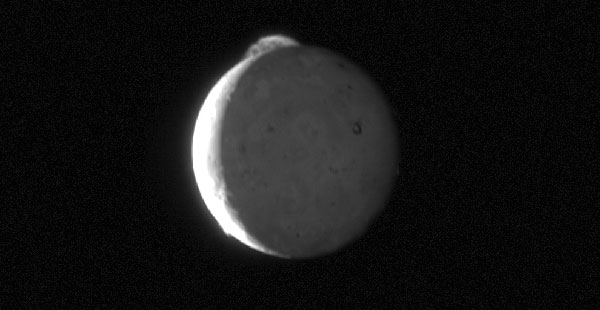

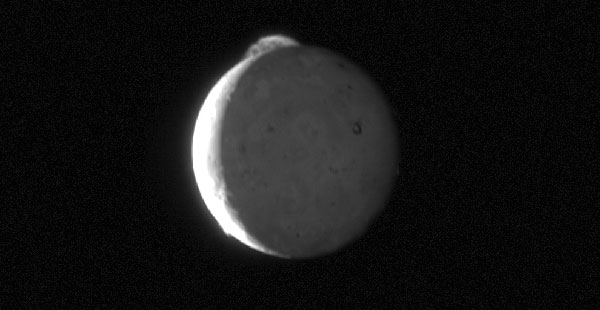

The Tvashtar "volcano" (click below image) near the north pole of

Io, was seen by the

New Horizons probe to be shooting a

plume more than 290 kilometers above the surface.

A NASA press release from that time

reported that,

"...the remarkable filamentary

structure in the Tvashtar plume is similar to details glimpsed

faintly in 1979 Voyager images of a similar plume produced by

Io's volcano Pele (below image).

However, no previous image by any

spacecraft has shown these mysterious structures so clearly."

It appears that the electrical circuit

on Io is concentrating Jupiter's current flow into several "plasma

guns" (below image), or dense plasma foci, as noted plasma physicist

Anthony Peratt

observed more than twenty years ago.

"Tidal kneading" of Io is not the

cause of its heat: Io is not being heated from within by

friction.

The most probable cause, based on

observational evidence and laboratory analysis, is that Io is

receiving an electrical input from Jupiter that is heating it up

through electromagnetic induction.

|