|

by Ray Villard from DiscoveryNews Website

What's little known is that there were several planned moon flights after Apollo 17.

They never happened. That is, except in the imagination of Hollywood producers. Filmmakers have now crafted a movie called "Apollo 18".

The real story of the lost missions of Apollo flights 18, 19, and 20, is a sad blank chapter in American space history. It has eerie parallels with the predicament NASA is now facing.

If the Apollo 18-20 flights were realized, school kids today could be looking at stunning photographs taken from the mountain-rimmed floors of the young impact craters Copernicus or Tycho, or the terrain on the far side of the moon, or the frozen volcanic lava flows from billions of years ago.

But the tumultuous political climate of the early 1970s pulled these aspirations down to Earth like the tug of gravity.

The early 1970s turmoil was fueled by the Vietnam War, soaring inflation, and social upheaval. The counterculture movement had no love for science, which was seen as being at the root of environmental damage. Our country had lost its will and its vision to boldly go deeper into space.

What's more, President Richard Nixon was no fan of former President John F. Kennedy’s Apollo moon project -- though Nixon was in office and got all the glory when we actually landed on the moon in 1969.

Nixon could have easily one-upped the Kennedy vision by proclaiming Mars as our next target. In fact, his Vice President Spiro Agnew touted the idea.

The mighty Saturn V booster could have gotten us to Mars by the mid 1980s using nuclear engines that were under development.

But declaring a "Man on Mars" program would have looked extravagant and would not have gotten popular support in the 1970s. (A human Mars flight would have probably cost at least $100 billion in 1970s dollars.)

There was also a "less than Right Stuff" fear of losing an Apollo crew. The Apollo 13 mishap was a very close call. The Apollo flights were the space age equivalent of seat-of-pants barnstorming.

A fatal accident seemed statistically likely. And, the consequences could be that the nation would lose its will to hurtle more humans deeper into space. (To the contrary, the deadly Challenger and Columbia Space Shuttle accidents actually spurred more public support for space travel.)

The timidity of avoiding increasingly risky moon missions is antithetical to the core American value of conquering the unknown frontier.

Following the recommendations of a presidential task force in 1969, Nixon directed NASA to stop building the muscular Saturn V’s and instead build the Space Shuttle, the first leg of an as yet realized space transportation infrastructure.

Abandoned Moon Missions

The last three Apollo 18-20 missions were still in the planning stages when Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon in 1969, but six short months after Armstrong's "giant leap for Mankind" transmission, NASA began canceling flights.

Polls showed that American public interest was already waning. Apollo was treated as the Space Olympics. We had beaten the Soviets to the moon. Game over...

The total savings of canceling the Apollo missions was a paltry $42 million - all the rockets and spacecraft had been built for the ambitious expeditions. Today, they are now rusting away as some of the most expensive museum pieces ever constructed.

What's more, the moon rock samples were derided by late night TV comedians because of the expense of fetching them and bringing them down to Earth. In reality, they are 4.4 billion year-old time capsules immeasurably more valuable than gold, ounce for ounce.

But in the early 1970s, there was no popular scientist with the communication skills of Carl Sagan (who didn't become a TV persona until later) or Neil DeGrasse Tyson, who could articulate the value of lunar science. The American public was tone deaf to what was self-evident to space geologists.

What is especially sad is that most potentially scientifically rewarding, dramatic, and risk-taking sites were planned for Apollo 18-20 missions.

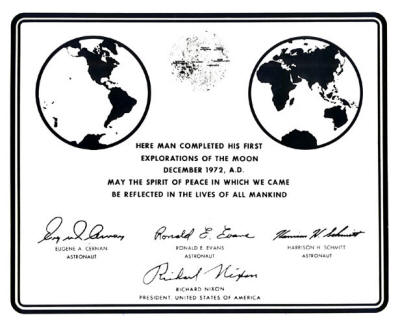

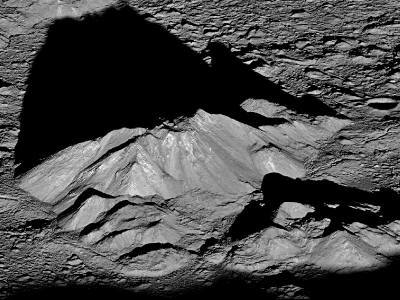

Possible landing sites were the young and large impact craters Copernicus, Gassendi and Tycho. Their craggy central peaks were thrust upward at the time of impacts, bringing material from deep within the lunar crust to the surface (Tycho's central peaks are shown in the leading image).

Astronaut-geologist Harrison Schmitt lobbied for NASA to send explorers on a daring flight to the crater Tsiolkovsky crater on the moon's far side.

Another site was Schroter's Valley (above), a deep, winding channel, hundreds of miles long, with a smaller inner channel that meanders just as slow rivers do on Earth. It is known to be rich in mineral resources.

In some sci-fi parallel universe, the Saturn Vs and Apollo spacecraft stay on the assembly line through the end of the 20th century. This enables a permanent space station to be built by 1980 with just four Saturn V launches. Astronauts plant an American flag on Mars in 1985.

By 1995, we test techniques for diverting Earth threatening asteroids. Immense space observatories catalog nearby inhabited exoplanets by 2008.

Today, instead all I can do is wistfully look at the dramatic NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photos of the craggy central peak in the crater Tycho. I can only imagine looking at a photo of an Apollo astronaut standing with that towering peak behind him.

My imaginary photo fades into the shadows of a lost frontier spirit.

English version for video click above image

Versión en Español

|