|

May 23, 2007

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

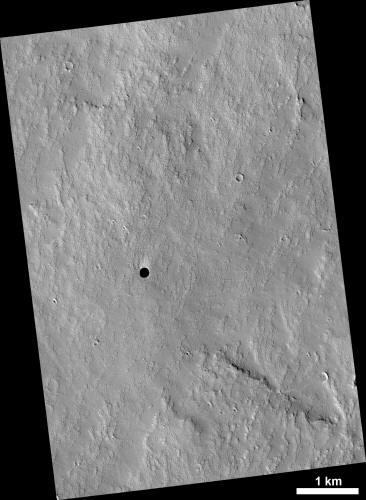

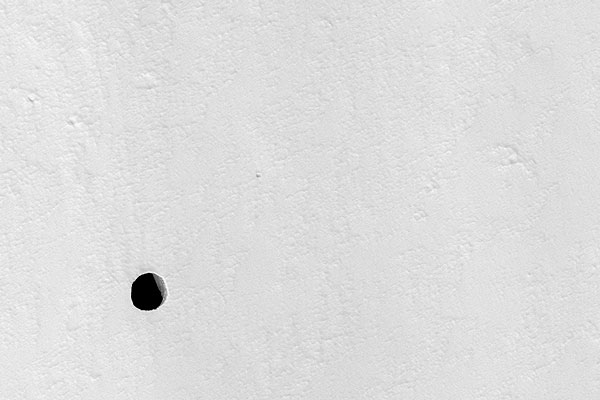

What's that black spot?

It's a window onto an underground world.

This black spot is one of seven possible entrances to subterranean caves identified on Mars by Glen Cushing, Tim Titus, J. Judson Wynne and Phil Christensen in a paper they presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in March (read it far below).

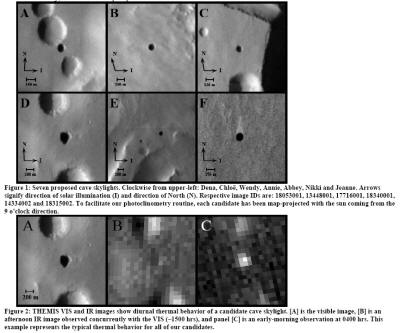

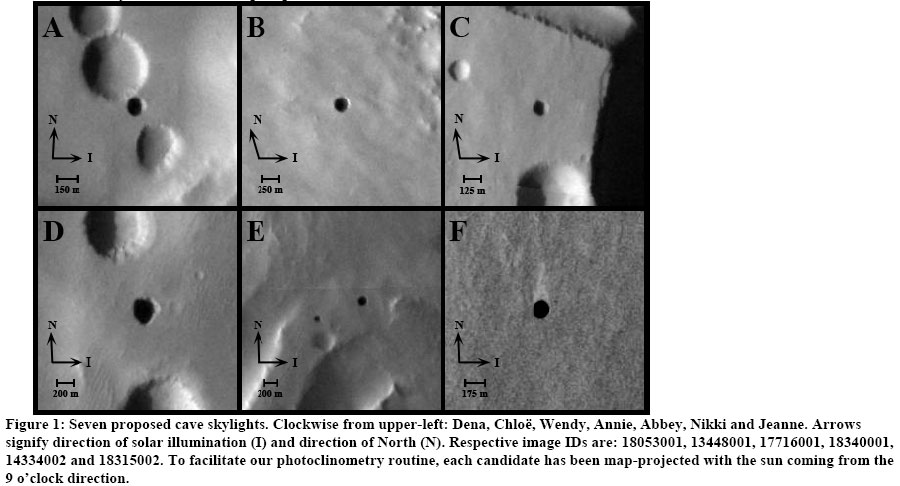

Here's the figure from their paper that shows the seven caves, which they refer to by the names Dena, Chloe, Wendy, Annie, Abbey, Nikki, and Jeanne:

Their identifications were based upon Mars Odyssey THEMIS images, which achieve resolutions of a little better than 20 meters per pixel; having spotted the caves, they requested that the sharper-eyed HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter target the spots for more detailed imaging. The image above is the first one of these, and it shows the cave entrance called Jeanne.

So what more can we learn from the HiRISE image?

Let's check it out at full resolution (you'll have to click to enlarge for the full glory of 25 centimeters per pixel, a number I still goggle at every time I think about it).

The hope for the HiRISE images was that we could see some details from inside the hole. But as you can see by the highly stretched version at right, there is absolutely nothing visible inside that hole. It's black black black black black. HiRISE is a very sensitive instrument, and Mars' dusty atmosphere scatters quite a bit of light around, so there is certainly light entering that cave hole and bouncing around the interior.

But it seems that the cave is so big and so deep that almost none of the light that enters the cave comes out. It's deep, and it's big; the hole that we see really is just a skylight on a big subterranean room.

How big?

We'll never know for sure without visiting it, but I expect that Cushing and his coauthors and the HiRISE team will be crunching the numbers on the illumination conditions and the sensitivity of the camera to put a lower limit on how deep that cave must be for HiRISE to be able to see nothing at all inside it.

Think about that.

All these orbiters at Mars, and most of them are just seeing the surface and atmosphere. To be sure, there are two instruments up there - MARSIS on Mars Express and SHARAD on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter - that are probing the shape of the subsurface with ground-penetrating radar. But neither of those instruments have the resolution necessary to tell us what the inside of this cave looks like. It might as well be in the greatest depths of space. Here there be dragons.

What's down there? Are there stalactites and stalagmites

and crystals, or is it just a vast open room or tunnel?

Possible Cave Skylights On Mars by G.E. Cushing1,2, T.N. Titus1, J.J. Wynne1,2, P.R. Christensen3,1 Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVIII (2007) U.S.G.S. 2255 N. Gemini Dr. Flagstaff, AZ 86001 2Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011 3Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287 from LunarAndPlanetaryInstitute Website

Introduction

Here we report the discovery of seven

candidate skylight entrances into subterranean caverns

(Figure 1). All seven are located on the flanks of Arsia Mons

(southernmost of the massive Tharsis ridge shield volcanoes), a

region with widespread collapse pits and grabens which may indicate

an abundance of subsurface void spaces [1,2].

Subterranean void spaces may be the only natural structures on Mars capable of protecting life from a range of significant environmental hazards. With an atmospheric density less than 1% of the Earth’s and practically no magnetic field, the Martian surface is essentially unprotected from micrometeoroid bombardment, solar flares, UV radiation and high-energy particles from space [3,4,5,6].

Additionally, intense dust storms occur

planet wide, and some regions exhibit temperature ranges that can

double over each diurnal cycle [7]. Besides general geological

interest, there is a strong motivation to find and explore Martian

caves to determine what advantages these structures may provide

future explorers. Furthermore, Martian caves are of great interest

for their biological possibilities because they may have provided

habitat for past (or even current) life [5,6,8].

Accordingly, Martian caves are among the

most desirable targets for astrobiological exploration

[11,12,13,14].

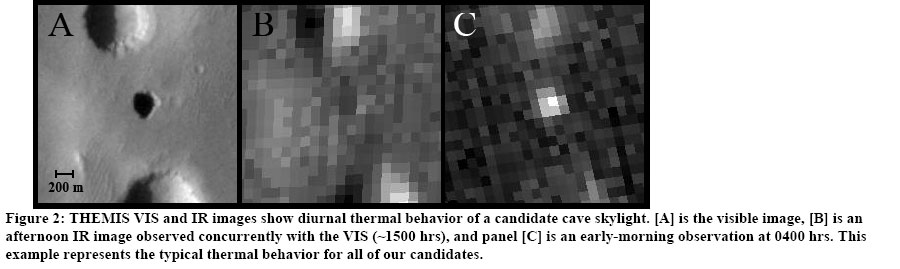

The Mars Odyssey Thermal Emission

Imaging System (THEMIS) collected the majority of data

for this study [15]. From a nadir perspective, THEMIS observes both

visible and thermal-infrared wavelengths during the afternoon (~

15001700 hrs), and IR wavelengths only for early-morning

observations (~ 0300-0500 hrs.) [15].

To aid in visualization, we have informally named these ‘seven sisters’ on Arsia Mons as: Dena, Chloë, Wendy, Annie, Abbey, Nikki and Jeanne (Figure 1 below).

Most of the candidates are adjacent to collapse pits or are directly in-line with collapse-pit chains, and appear to have formed by similar processes.

They are visibly distinct from collapse pits, however, by a lack of visible (sunlit) walls or floors. These proposed skylights also lack the visible characteristics (such as raised rims or ejecta patterns) that would associate them with impact craters.

Thermal behaviors furthermore confirm

they are not misidentified surface features such as dark sand or

rock.

However, a fortunate MOC observation of

Dena at ~2 p.m. (R0800159) actually does show an illuminated floor,

allowing us to tightly constrain the depth using a 1-D

photoclinometry routine. This routine returns a depth of ~130 m for

the illuminated floor, while the minimum depth estimated from the

THEMIS observation is only ~80 m.

Analyses of the candidates suggest they are not of impact origin, not patches of dark surface material, and are likely skylight openings into subsurface cavernous spaces. Visible observations show dark holes with sufficient depth that no illuminated floors (incidence angles ≥ 61.5°) can be seen from a nadir perspective (Thermal-infrared data suggest temperatures inside these features remain nearly constant throughout each diurnal cycle.)

Figure 2 shows afternoon temperatures for Annie that are warmer than the shadows of adjacent collapse pits, and cooler than sunlit portions. Meanwhile, nighttime temperatures for this candidate are warmer than all nearby surfaces.

Such is the behavior we would expect of a cavern floor that receives little or no daily solar insolation [9,10].

Wendy, Dena, Annie and Jeanne are the strongest candidates because they have the most complete data sets; i.e., they have both VIS and diurnal IR coverage, and they are large enough to be clearly identified at 100-m resolution. Chloë, Abbey and Nikki are also strong candidates because they have the same visible and thermal characteristics as the other candidates.

Their minimum depths could not be constrained, however, because of late-afternoon observations when the sun is too low to shine deeply into the pits.

Additional observations are necessary - particularly those at different times of day and from an off-nadir perspective. These candidates cannot be physically explored with our current state of technology because the targets are too small and specific, and the atmosphere at these elevations is too thin for a lander to slow down or maneuver sufficiently to reach them.

The astrobiological significance

may also be reduced at these elevations because microbial life, if

it ever existed on Mars, may not have occurred at these elevations.

However, possible evidence of liquid water at the Martian surface

was recently identified by Malin, et al. (2006) [16]. If liquid

water does exist at or near the surface, then caves at lower

elevations could hold natural reservoirs, greatly improving the

possibilities for past or present microbial life.

This discovery presents us with new insights and new challenges for the future of Mars exploration.

References:

(PSP_004847_1745:2007-08-29) August 29, 2007 from HiRISE-HighResolutionImagingScienceExperiment Website

Click above image

|