|

February 27,

2013

from

ITechPost Website

A wood frog rests

beside a chanterelle mushroom.

Credit:Reuters

Chemists at MIT are testing compounds based on a chemical secreted

by fungi. The compounds could potentially be used in formulating

drugs to treat cancer.

Years ago, a team led by Mohammed Movassaghi, associate

professor at MIT, synthesized a complex fungal compound. Previous

studies of the compound called 11, 11'-dideoxyverticillin found that

it exhibited cancer-fighting characteristics.

Movassaghi asserts that

a more comprehensive study has to be conducted to determine drug

development possibilities.

"There's a lot of

data out there, very exciting data, but one thing we were

interested in doing is taking a large panel of these compounds,

and for the first time, evaluating them in a uniform manner,"

said Movassaghi.

Scientists believe that

compounds naturally produced by fungi known as

pipolythiodiketopiperazine (ETP) alkaloids are emitted to help fungi

fight organisms that try to invade their territory.

The researchers synthesized natural ETP in the lab and produced

similar compounds that they believed the have anti-cancer

characteristics. More compounds were created for the new study,

forming a variety by either adding or removing chemical groups.

The study was published in Chemical Science online, explaining how

60 compounds were designed and tested for their ability to destroy

cancer cells.

"What was

particularly exciting to us was to see, across various cancer

cell lines, that some of them are quite potent," said Movassaghi.

The 60 compounds were

tested on two human cancers, cervical cancer and lymphoma.

Lung, kidney and breast

cancers were later tested using 25 of the best compounds. It was

found that dimeric compounds, formed by combining two identical

molecules, were more effective at killing cancer cells compared to

monomers, which are single-molecule compounds.

The compounds were

selective and destroyed cancer cells 1,000 times greater than

they did healthy blood cells.

The research team included Movassaghi and his colleagues at MIT and

the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). Nicolas

Boyer, an MIT postdoc, is the lead author of the paper.

Many antibiotics, including penicillin, were derived from chemicals

extracted from or based on chemicals from fungi. Alexander

Fleming made the discovery in 1929 that the fungal contaminant

described as "Penicillium notatum" was effective against many forms

of bacteria.

Chemists Find Help from Nature in

Fighting Cancer

-

Research Update -

by Anne

Trafton

MIT News Office

February 27, 2013

from

MIT Website

Study of

several dozen compounds

based on a

fungal chemical

shows potent

anti-tumor activity.

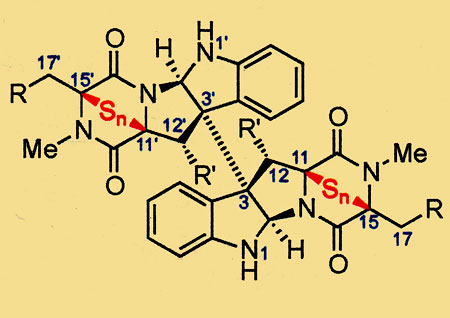

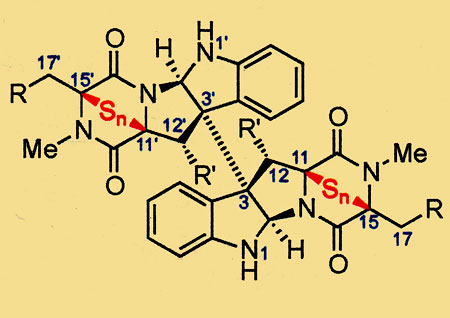

MIT chemists designed

many variants

of

epipolythiodiketopiperazine (ETP) alkaloids

and tested them for

anticancer activity.

A representative ETP

structure is shown.

Graphic courtesy of the researchers

Inspired by a chemical

that fungi secrete to defend their territory, MIT chemists have

synthesized and tested several dozen compounds that may hold promise

as potential cancer drugs.

A few years ago, MIT researchers led by associate professor of

chemistry Mohammad Movassaghi became the first to chemically

synthesize 11,11’-dideoxyverticillin, a highly complex fungal

compound that has shown anti-cancer activity in previous studies.

This and related

compounds naturally occur in such small amounts that it has been

difficult to do a comprehensive study of the relationship between

the compound’s structure and its activity - research that could aid

drug development, Movassaghi says.

“There’s a lot of

data out there, very exciting data, but one thing we were

interested in doing is taking a large panel of these compounds,

and for the first time, evaluating them in a uniform manner,”

Movassaghi says.

In the new study,

recently published online in the journal Chemical Science (Synthesis

and Anticancer Activity of Epipolythiodiketopiperazine Alkaloids),

Movassaghi and colleagues at MIT and the University of Illinois

at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) designed and tested 60 compounds for

their ability to kill human cancer cells.

“What was

particularly exciting to us was to see, across various cancer

cell lines, that some of them are quite potent,” Movassaghi

says.

Lead author of the paper

is MIT postdoc Nicolas Boyer.

Other authors are MIT

graduate student Justin Kim, UIUC chemistry professor Paul Hergenrother and UIUC graduate student

Karen Morrison.

Improving

nature’s design

Many of the compounds tested in this study, known as

epipolythiodiketopiperazine (ETP) alkaloids, are naturally produced

by fungi. Scientists believe these compounds help fungi prevent

other organisms from encroaching on their territory.

In the process of synthesizing ETP natural products in their lab,

the MIT researchers produced many similar compounds that they

suspected might also have anti-cancer activity. For the new study,

they created even more compounds by systematically varying the

natural structures - adding or removing certain chemical groups from

different locations.

The researchers tested 60 compounds against two different human

cancer cell lines - cervical cancer and lymphoma.

Then they chose the best

25 to test against three additional lines, from lung, kidney and

breast tumors. Overall, dimeric compounds - those with two ETP

molecules joined together - appeared to be more effective at killing

cancer cells than single molecules (known as monomers).

The structure of an ETP natural product typically has at least one

set of fused rings containing one or more sulfur atoms that link to

a six-member ring known as a cyclo-dipeptide.

The researchers found

that another key to tumor-killing ability is the arrangement and

number of these sulfur atoms: Compounds with at least two sulfur

atoms were the most effective, those with only one sulfur atom were

less effective, and those without sulfur did not kill tumor cells

efficiently.

Other rings typically have chemical groups of varying sizes attached

in certain positions; a key position is that next to the ETP ring.

The researchers found that the larger this group, the more powerful

the compound was against cancer.

The compounds that kill cancer cells appear to be very selective,

destroying them 1,000 times more effectively than they kill healthy

blood cells.

The researchers also identified sections of the compounds that can

be altered without discernibly changing their activity.

This is useful because

it could allow chemists to use those points to attach the compounds

to a delivery agent such as an antibody that would target them to

cancer cells, without impairing their cancer-killing ability.

Complex

synthesis

Larry Overman, a professor of chemistry at the University of

California at Irvine, says the new study is an impressive advance.

“Movassaghi and

coworkers reveal for the first time a number of relationships

between the chemical structure of molecules in the ETP series

and their in-vitro anti-cancer activity,” says Overman, who was

not part of the research team.

“Knowledge of this

type will be essential for the future development of ETP-type

molecules into attractive clinical candidates and potential

novel anti-cancer drugs.”

Now that they have some

initial data, the researchers can use their findings to design

additional compounds that might be even more effective.

“We can go in with

far greater precision and test the hypotheses we’re developing

in terms of what portions of the molecules are most significant

at retaining or enhancing biological activity,” Movassaghi says.

The research was funded

by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

|