|

12 - PHOBOS -

MALFUNCTION OR STAR WARS INCIDENT?

On October 4, 1957, the

Soviet Union launched Earthlings’ first artificial satellite.

Sputnik 1, and set Mankind on a road that has led Man to the Moon

and his spacecraft to the edge of the Solar System and beyond.

On July 12, 1988, the Soviet Union launched an unmanned spacecraft

called Phobos 2 and may have provided Mankind with its first Star

Wars incident—not the “Star Wars” nickname of America’s Strategic

Defense Initiative (SDI), but a war with people from another world.

Phobos 2 was one of two unmanned satellites, the other being Phobos

1, that were set off from Earth in July 1988, headed toward the

planet Mars. Phobos 1, reportedly because of a radio command error,

was lost two months later. Phobos 2 arrived safely at Mars in

January 1989 and entered into orbit around Mars as the first step at

its destination toward its ultimate goal—to transfer to an orbit

that would make it fly almost in tandem with

the Martian moonlet

called Phobos (hence the spacecraft’s name) and explore the moonlet

with highly sophisticated equipment that included two packages of

instruments to be placed on the moonlet’s surface.

All went well until Phobos 2 aligned itself with Phobos, the Martian

moonlet. Then, on March 28, 1989, the Soviet mission control center

acknowledged sudden communication “problems” with the spacecraft;

and Tass, the official Soviet news agency, reported that,

“Phobos 2

failed to communicate with Earth as scheduled after completing an

operation yesterday around the Martian moon Phobos. Scientists at

mission control have been unable to establish stable radio contact.”

These admissions left the impression that the problem was not

incurable and were accompanied by assurances that mission control scientists

were engaged in maneuvers to reestablish contact with the

spacecraft. Soviet space program officials as well as many Western

specialists were aware that the Phobos mission represented an

immense investment in terms of finance, planning, effort, and

prestige. Although launched by the Soviets, the mission in reality

represented an international effort on an unprecedented scale, with

more than thirteen European countries (including the European Space

Agency and major French and West German scientific institutions)

participating officially and British and American scientists

participating “personally” (with their governments1 knowledge and

blessing).

It was thus understandable that the “problem” was at

first represented as a break in communications that could be

overcome in a matter of days. Soviet television and press reports

played down the seriousness of the occurrence, emphasizing that

attempts were being made to reestablish links with the spacecraft.

In fact, American scientists associated with the program were not

officially informed of the nature of the problem and were led to

believe that the communications breakdown was caused by the

malfunction of a low-power backup transmitting unit that had been in

use since the principal transmitter had failed earlier.

But on the next day, while the public was still being reassured that

a resumption of contact with the spacecraft was achievable, a

high-ranking official at Glavkosmos, the Soviet space agency, hinted

that there indeed was no such hope. “Phobos 2 is ninety-nine percent

lost for good,” Nikolai A. Simyonov said; on that day, his choice of

words —not that contact with the spacecraft was lost but that the

spacecraft itself was “lost for good”—was not paid any particular

heed.

On March 30, in a special report from Moscow to

The New York

Times, Esther B. Fein mentioned that Vremya, the main evening news

program on Soviet television, “rapidly rattled off the bad news

about Phobos” and focused its report instead on the successful

research the spacecraft had already accomplished. Soviet scientists

appearing on the program,

“displayed some of the space images, but

said it was still not clear what clues they offered to understanding

Mars, Phobos, the Sun and interplanetary space.”

What “images” and what “clues” were they talking about?

This became clearer the following day, when reports published in the

European press (but for some reason not in the U.S. media) spoke of

an “unidentified object” that was seen “in the final pictures taken

by the spaceship,” which showed an “inexplicable” object or

“elliptical shadow” on Mars. This was an avalanche of puzzling words

out of Moscow!

The Spanish daily La Epoca, for example (Fig. 92),

headlined the dispatch by the Moscow correspondent of the European

news agency EFE “Phobos 2 Captured Strange Photos of Mars Before

Losing Contact With Its Base.”

Fig. 92

The text of the dispatch, in

translation, read as follows:

The TV newscast “Vremya” revealed yesterday that the space probe

Phobos 2, which was orbiting above Mars when Soviet scientists lost

contact with it on Monday, had photographed an unidentified object

on the Martian surface seconds before losing contact.

The TV broadcast devoted a long segment to the strange pictures

taken by the spaceship before losing contact, and Figure 92 showed the two most important

pictures, in which a large shadow is visible in one of the pictures

and in the other. Scientists characterized the final picture taken

by the spaceship, in which the thin ellipse can be clearly seen, as

“inexplicable.”

The phenomenon, it was stated, could not be an optical illusion

because it was captured with the same clarity both by color cameras

as well as by cameras taking infrared images.

One of the members of the Permanent Space Commission who had worked

around the clock to reestablish contact with the lost space probe

stated on Soviet television that in the opinion of the commission’s

scientists the object “looked like a shadow on the surface of Mars.”

According to calculations by researchers from the Soviet Union the

“shadow” that the last photo taken by Phobos 2 shows is some twenty

kilometers [about 12.5 miles] long.

A few days earlier, the spaceship had already recorded an identical

phenomenon, except that in that instance the “shadow” was between

twenty-six to thirty kilometers [about 16 to 19 miles] long.

The reporter from “Vremya” asked one of the members of the special

commission if the shape of the “phenomenon” didn’t suggest to him a

space rocket, to which the scientist responded, “This is to

fantasize.” (Here follow details of the mission’s original assignments.)

Needless to say, this is an amazing and literally “out of this

world” report that raises as many questions as it answers.

The loss

of contact with the spacecraft was associated, by implication if not

in so many words, with the observation by the spacecraft of “an

object on the Martian surface seconds before.” The culprit “object”

is described as “a thin ellipse” and is also called “a phenomenon”

as well as “a shadow.” It was observed at least twice—the report

does not state whether in the same location on the surface of

Mars—and is capable of changing its size: the first time it was

about 12,5 miles long; the second and fatal time, about 16 to 19

miles long. And when the “Vremya” reporter wondered whether it was a “space rocket,” the scientist responded,

“This is to fantasize.” So, what was—or is—it?

The authoritative weekly Aviation Week & Space Technology, in its

issue of April 3, 1989, printed a report of the incident based on

several sources in Moscow, Washington, and Paris (the authorities in

the last being deeply involved because an equipment malfunction

would have reflected badly on the French contribution to the

mission, whereas an “act of God” would exonerate the French space

industry).

The version given AW&ST treated the occurrence as a

“communications problem” that remained unresolved in spite of a week

of attempts to “re-establish contact.” It included the information

that program officials at the Soviet Space Research Institute in

Moscow said that the problem occurred “after an imaging and data

gathering session,” following which Phobos 2 had to change the

orientation of its antenna.

“The data-gathering segment itself

apparently proceeded as planned, but reliable contact with Phobos 2

could not be established afterward.”

At the time, the spacecraft was

in a near-circular orbit around Mars and in the phase of “final

preparations for the encounter with Phobos” (the moonlet).

While this version attributed the incident to a

“loss-of-communications” problem, a report a few days later in

Science (April 7, 1989) spoke of “the apparent loss of Phobos

2”—loss of the spacecraft itself, not just of the communications

link with it. It happened, the prestigious journal stated, “on 27

March as the spacecraft turned from its normal alignment with Earth

to image the tiny moon Phobos that was the primary mission target.

When it came time for the spacecraft to turn itself and its antenna

automatically back toward Earth, nothing was heard.”

The journal then continued with a sentence that remains as

inexplicable as the whole incident and the “thin ellipse” on the

surface of Mars. It states:

A few hours later, a weak transmission was received, but controllers

could not lock onto the signal. Nothing was heard during the next

week.

Now, as a rereading of all the previous reports and statements will

confirm, the incident was described as a sudden and total loss of the “communications

link.” The reason given was that the spacecraft, having turned its

antennas to scan Phobos, failed to turn its antenna back toward

Earth due to some unknown reason. But if the antenna remained stuck

in a position facing away from Earth, how could “a weak

transmission” be received “a few hours later”? And if the antenna

did in fact turn itself back toward Earth properly, what caused the

abrupt silence for several hours, followed by the transmission of a

signal too weak to be locked onto?

The question that arises is indeed a simple one: Was the spacecraft

Phobos 2 hit by “something” that put it out of commission, except

for a last gasp in the form of a weak signal hours later?

There was one more report, from Paris, in AW&ST of April 10, 1989.

Soviet space scientists, it said, suggested that Phobos 2 “did not

stabilize itself on the proper orientation to have the high-gain

antenna pointing earthward.” This obviously puzzled the editors of

the magazine because, its report said, the Phobos2 spacecraft was

“three-axis stabilized” by technology developed for the Soviet Venera spacecraft, which had performed perfectly on Venus missions.

The mystery thus is, what caused the spacecraft to destabilize

itself? Was it a malfunction, or was there an extraneous

cause—perhaps an impact?

The weekly’s French sources provided this tantalizing detail:

One controller at the Kaliningrad control center said the limited

signals received after conclusion of the imaging session gave him

the impression he was “tracking a spinner.” Phobos 2, in other

words, acted as if it was in a spin. Now, what was Phobos 2

“imaging” when the incident occurred? We already have a good idea

from the “Vremya” and European press agency reports.

But here is

what the AW&ST report from Paris states, quoting Alexander Dunayev,

chairman of the Soviet Glavkosmos space administration:

One image appears to include an

odd-shaped object between the spacecraft and Mars. It may be

debris in the orbit of Phobos or could be Phobos 2’s autonomous

propulsion

sub-system that was jettisoned after the spacecraft was injected

into Mars orbit—we just don’t know.”

This statement must have been

made with quite a tonguein-cheek attitude. The Viking orbiters left

no debris in Mars orbit, and we know of no other “debris” resulting

from Earth originated activities. The other “possibility,” that the

object orbiting Mars between the planet and the spacecraft Phobos 2

was a jettisoned part of the spacecraft, can be readily dismissed

once one looks at the shape and structure of Phobos 2 (Fig. 93);

none of its parts had the shape of a “thin ellipse.”

Moreover, it

was disclosed on the “Vremya” program that the “shadow” was 12.5,

16, or 19 miles long. Now, it is true that an object can throw a

shadow much longer than itself, depending on the angle of sunlight;

still, a part of Phobos 2 that was only a few feet in length could

hardly throw a shadow measured in miles. Whatever had been observed

was neither debris nor a jettisoned part.

Fig. 93

At the time I wondered why the official speculation omitted what was

surely the most natural and believable third possibility, that what

had been observed was indeed a shadow—but the shadow of Phobos, the

Martial moonlet itself. It has Figure 93 most often been described as “potato-shaped”

(Fig. 94) and measures about seventeen miles across—just about the

size of the “shadow” mentioned in the initial reports. In fact. I

recalled seeing a Mariner 9 photograph of an eclipse on Mars caused

by the shadow of Phobos.

Couldn’t that be, I thought, what the fuss

was all about, at least regarding the “apparition,” if not what had

caused the spacecraft, Phobos 2, to be lost? The answer came about

three months later. Pressed by their international participants in

the Phobos missions to provide more definitive data, the Soviet

authorities released the taped television transmission Phobos 2 sent

in its last moments—except for the last frames, taken just seconds before the spacecraft

fell silent.

Figure 94

The television clip was shown by some TV stations in

Europe and Canada as part of weekly “diary” programs, as a curiosity

and not as a hot news item.

The television sequence thus released focused on two anomalies. The

first was a network of straight lines in the area of the Martian

equator; some of the lines were short, some longer, some thin, some

wide enough to look like rectangular shapes “embossed” in the

Martian surface. Arranged in rows parallel to each other, the

pattern covered an area of some six hundred square kilometers (more

than two hundred thirty square miles). The “anomaly” appeared to be

far from a natural phenomenon.

The television clip was accompanied by a live comment by Dr. John Becklake of England’s Science Museum. He described the phenomenon as

very puzzling, because the pattern seen on the surface of Mars was

photographed not with the spacecraft’s optical camera but with its

infrared camera—a camera that takes pictures of objects using the

heat they radiate, and not by the play of light and shadow on them.

In other words, the pattern of parallel lines and rectangles

covering an area of almost two hundred fifty square miles was a

source of heat radiation.

It is highly unlikely that a natural

source of heat radiation (a geyser or a concentration of radioactive

minerals under the surface, for example) would create such a perfect

geometric pattern. When viewed over and over again, the pattern

definitely looks artificial; but what it was, the scientist said, “I

certainly don’t know.”

Since no coordinates for the precise location of this “anomalous

feature” have been released publicly, it is impossible to judge its

relationship to another puzzling feature on the surface of Mars that

can be seen in

Mariner 9 frame 4209-75. It is also located in the

equatorial area (at longitude 186.4) and has been described as

“unusual indentations with radial arms protruding from a central

hub” caused (according to NASA scientists) by the melting and

collapse of permafrost layers.

The design of the features, bringing

to mind the structure of a modern airport with a circular hub from

which the long structures housing the airplane gates radiate, can be

better visualized when the photograph is reversed (showing

depressions as protrusions—Fig. 95).

Fig. 95

We now come

to the second “anomaly” shown on the television segment. Seen on the

surface of Mars was a clearly defined dark shape that could indeed

be described, as it was in the initial dispatch from Moscow, as a

“thin ellipse” (Plate N is a still from the Soviet television clip).

It was certainly different from the shadow of Phobos recorded

eighteen years earlier by Mariner 9 (Plate O). The latter cast a

shadow that was a rounded ellipse and fuzzy at the edges, as would

be cast by the uneven surface of the moonlet.

Plate N

The “anomaly” seen in

the Phobos 2 transmission was a thin ellipse with very sharp rather

than rounded points (the shape is known in the diamond trade as a

“marquise”) and the edges, rather than being fuzzy. Plate N stood out sharply against a kind of halo on the

Martian surface. Dr. Becklake described it as “something that is

between the spacecraft and Mars, because we can see the Martian

surface below it,” and stressed that the object was seen both by the

optical and the infrared (heat-seeking) camera. All these reasons

explain why the Soviets have not suggested that the dark, “thin

ellipse” might have been the shadow of the moon let.

Plate O

While the image was held on the screen,

Dr. Becklake explained that

it was taken as the spacecraft was aligning itself with Phobos (the

moonlet).

“As the last picture was halfway through,” he said, “they

[Soviets] saw something which should not be there.”

The Soviets, he

went on to state, “have not yet released this last picture, and we

won’t speculate on what it shows.”

Since the last frame or frames have not yet been publicly released

even a year after the incident, one can only speculate, surmise, or

believe rumors, according to which the last frame, Plate O halfway through its

transmission, shows the “something that should not be there” rushing

toward Phobos 2 and crashing into it, abruptly interrupting the

transmission.

Then there was, according to the reports mentioned

earlier, a weak burst of transmission some hours later, too garbled

to be clear. (This report, incidentally, belies the initial

explanation that the spacecraft could not turn its antennas back to

an Earth-transmitting position).

In the October 19, 1989 issue of Nature, Soviet scientists published

a series of technical reports on the experiments Phobos 2 did manage

to conduct; of the thirty-seven pages, a mere three paragraphs deal

with the spacecraft’s loss. The report confirms that the spacecraft

was spinning, either because of a computer malfunction or because

Phobos 2 was “impacted” by an unknown object (the theory that the

collision was with “dust particles” is rejected in the report).

So what was it that collided or crashed into Phobos 2, the

“something that should not be there”? What do the last frame or frames, still secret, show? In his careful

words to AW&ST, the chairman of the Soviet equivalent of NASA

referred to that last frame when he tried to explain the sudden loss

of contact, saying,

“One image appears to include an odd-shaped

object between the spacecraft and Mars.”

If not “debris,” or “dust,” or a “jettisoned part of Phobos 2,” what

was the “object” that all accounts of the incident now admit

collided with the spacecraft—an object with an impact strong enough

to put the spacecraft into a spin, an object whose image was

captured by the last photographic frames? “We just don’t know,” said

the chief of the Soviet space program.

But the evidence of an ancient space base on Mars and the odd-shaped

“shadow” in its skies add up to an awesome conclusion:

What the secret frames hide is evidence that the loss of Phobos 2

was not an accident but an incident. Perhaps the first incident in a

Star Wars—the shooting down by Aliens from another planet of a

spacecraft from Earth intruding on their Martian base.

Has it occurred to the reader that the Soviet space chief’s answer,

“We just don’t know” what the “odd-shaped object between the

spacecraft and Mars” was, is tantamount to calling it a UFO—an

Unidentified Flying Object?

For decades now, ever since the phenomenon of what was first called

Flying Saucers and later UFOs became a worldwide enigma, no

self-respecting scientist would touch the subject even with a ten

foot pole—except, that is, to ridicule the phenomenon and whoever

was foolish enough to take it seriously. The “modern UFO era,”

according to Antonio Huneeus, a science writer and internationally

known lecturer on UFOs, began on June 24, 1947, when Kenneth Arnold,

an American pilot and businessman, sighted a formation of nine

silvery disks flying over the Cascade Mountains in the state of

Washington. The term “Flying Saucer” that then came into vogue was

based on Arnold’s description of the mysterious objects.

While the “’Arnold incident” was followed by alleged sightings

across the United States and other parts of the world, the UFO case

deemed most significant and one still discussed (and dramatized on

television) is the alleged crash of an “alien spacecraft” on July 2,

1947—a week after the Arnold sighting—on a ranch near Roswell, New

Mexico. That evening a bright, disk-shaped object was seen in the

area’s skies; the next day a rancher, William Brazel, discovered

scattered wreckage in his field northwest of Roswell.

The wreckage

and the “metal” of which it was made looked odd, and the discovery

was reported to the nearby Army Air Corps base at Roswell Field

(which then had the world’s only nuclear-weapons squadron.) Major

Jesse Marcel, an intelligence officer, together with an officer from

the counterintelligence corps, went to examine the debris. The

pieces, engineered in various shapes, looked and felt like balsa

wood but were not wood; they would neither burn nor bend, no matter

how the investigators tried. On some beam-shaped pieces there were

geometric markings that were later referred to as “hieroglyphics.”

On returning to the base, the officer in charge instructed the

base’s public relations officer to notify the press (in a release

dated July 7, 1947) that AAF personnel had retrieved parts of a

“crashed flying saucer.” The release made headline news in The

Roswell Daily Record (Fig. 96) and was picked up by a press wire

service in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Within hours a new official

statement, superseding the first, claimed instead that the debris

was part of a fallen weather balloon. Newspapers printed the

retraction; and, according to some reports, radio stations were

ordered to stop broadcasting the first version by being told, “Cease

transmission. National security item. Do not transmit.”

In spite of the revised version and ensuing official denials

of any “flying saucer” incident at Roswell, many of those

personally involved in that incident persist, to this very day,

in adhering to the first version. Many also assert that at a nearby

crash site of another “flying saucer” (in an area west of Socorro,

New Mexico), civilian witnesses had seen not only the wreckage but

also several bodies of dead humanoids.

Figure 96

These

bodies, as well as bodies allegedly of “aliens” who crashed

after these two events, have been variously reported to have

undergone examination at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

According to a document known in UFO circles as

MJ-12 or Majestic-12

(the two, some claim, are not identical), President Truman formed,

in September, 1947, a blue-ribbon, top-secret committee to deal with

the Roswell and related incidents, but the authenticity of this

document remains unverified.

What is known for a fact is that

Senator Barry Goldwater, who either chaired or was a senior member

of U.S. Senate committees on Intelligence, Armed Services, Tactical

Warfare, Science, Technology, and Space and others with a bearing on

the subject, was repeatedly refused admission to a so-called Blue

Room at that air base.

“I have long ago given up acquiring access to

the so-called blue room at Wright-Patterson, as I have had one long

string of denials from chief after chief,” he wrote to an inquirer

in 1981.

“This thing has gotten so highly classified... it is

just impossible to get anything on it.”

Reacting to continued reporting of UFO sightings and unease about

excessive official secrecy, the U.S. Air Force conducted several

investigations of the UFO phenomenon through such projects as Sign, Grudge, and

Blue Book. Between 1947 and 1969 about thirteen thousand reports of

UFOs were investigated, and they were by and large dismissed as

natural phenomena, balloons, aircraft, or just imagination. Some

seven hundred sightings, however, remained unexplained.

In 1953, the

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s Office of Scientific Intelligence

convened a panel of scientists and government officials. Known as

the Robertson Panel, the group spent a total of twelve hours viewing

UFO films and studying case histories and other information and

found that “reasonable explanations could be suggested for most

sightings. The evidence presented, it was reported, showed how the

remaining cases could not be explained by probable causes, “leaving

‘extra-terrestrials’ as the only remaining explanation in many

cases,” although, the panel noted, “present astronomical knowledge

of the solar system makes the existence of intelligent beings. . .

elsewhere than on the Earth extremely unlikely.”

While official

“debunking” of UFO reports continued (another investigation along

the same lines and with similar conclusions was the officially

commissioned Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects by the

University of Colorado, conducted from 1966 to 1969), the number of

sightings and “encounters” continued to rise, and civilian amateur

investigative groups have sprung up in numerous countries. The

encounters are now classified by these groups; those of the “second

kind” are instances where physical evidence (landing markings or

interference with machinery) is left behind by the UFOs; and those

of the “third kind,” where contact takes place with the UFO’s

occupants.

Descriptions of the UFOs once were varied, from “flying

saucers” to “cigar-shaped.” Now most describe them as circular

in construction and, when landing, as resting on three or

four extended legs. Descriptions of the occupants also are more

uniform: “humanoids” three to four feet tall, with large, hairless

heads and very big eyes (Fig. 97a, b). According to a

purported eye-witness report by a military intelligence officer

who saw,

“recovered UFOs and alien bodies” at a “secret base

in Arizona,” the humanoids “were very, very white; there

were no ears, no nostrils. There were only openings: a very small

mouth and their eyes were large. There was no facial hair, no

head hair, no pubic hair. They were nude. I think the tallest

one could have been about three-and-a-half feet, maybe a little

taller.”

Figure 97

The witness added that he saw no genitals and no breasts, although

some humanoids looked male and some female.

The multitude of people reporting sightings or contacts come from

every geographical or occupational background. President Jimmy

Carter, for example, disclosed in a campaign speech in 1976 that he

had seen a UFO. He moved to “make every piece of information this

country has about UFO sightings available to the public and the

scientists”; but for reasons that were never given, his campaign

promise was not kept.

Besides the official U.S. policy of

“debunking” UFO reports, what has irked UFO believers in the United

States is the official tendency to give the impression that

government agencies have lost interest even in investigating UFO

reports, whereas it has repeatedly come to light that this or that

agency, including NASA, is keeping a close eye on the subject. In

the Soviet Union, on the other hand, the Institute of Space Research

published in 1979 an analysis of "Observations of Anomalous

Atmospheric Phenomena

in the USSR” (“’anomalous atmospheric phenomena” is the Russian term

for UFOs), and in 1984 the Soviet Academy of Sciences formed a

permanent commission to study the phenomena. On the military side,

the subject came under the jurisdiction of the GRU (Chief

Intelligence Directorate of the Soviet General Staff); its orders

were to discover whether UFOs were “secret vehicles of foreign

powers,” unknown natural phenomena, or “manned or unmanned

extraterrestrial probes engaged in the investigation of Earth.”

Numerous reported or purported sightings in the Soviet Union

included some by Soviet cosmonauts. In September 1989, the Soviet

authorities took the significant step of having Tass, the official

news agency, report a UFO incident in the city of Voronezh in a

manner that made front pages worldwide; in spite of the usual

disbelief, Tass stood by its story. The French authorities have also

been less “debunkative” (to coin a word) than U.S. officials. In

1977 the French National Space Agency (CNES), headquartered in

Toulouse, established the Unidentified Aerospace Phenomena Study

Group (GEPAN); it was recently renamed the Service d’Expertise des

Phenomenes de Rentree Atmospherique, with the same task of following

up and analyzing UFO reports.

Some of the more celebrated UFO cases

in France included follow-up analyses of the sites and soils where

the UFOs were seen to have landed, and the results showed the

“presence of traces for which there is no satisfactory explanation.”

Most French scientists have shared the disdain of their colleagues

from other countries for the subject, but among those who did get

involved and voiced an opinion, the consensus has been to see in the

phenomena “a manifestation of the activities of extraterrestrial

visitors.”

In Great Britain, the veil of secrecy over the UFO

phenomenon has held tight in spite of such efforts as the inquiring

UFO Study Group of the House of Lords initiated by the Earl of Clancarty (a group I had the privilege to address in 1980). The

British experience, as well as that of many other countries, is

reported in some detail in Timothy Good’s book

Above Top Secret

(1987). The wealth of documents quoted or reproduced in Good’s book

leads to the conclusion that at first the various governments

“covered up” their findings because UFOs were suspected of being advanced aircraft of another superpower, and

admission of the enemy’s superiority was not in the national

interest.

But once the extraterrestrial nature of the UFOs became

the primary guess (or knowledge), the memory of such panics as was

caused by Orson Wells' “War of the Worlds" radio broadcast was

used as the rationale for what so many UFO enthusiasts call a cover

up.

The real problem many have with UFOs is the lack of a cohesive and

plausible theory to explain their origin and purpose. Where do they

come from? Why?

I myself have not encountered a UFO, to say nothing of being

abducted and experimented upon by humanlike beings with elliptical

heads and bulging eyes—incidents witnessed and experienced, if such

claims be true, by many others. But when asked for my opinion,

whether I “believe in UFOs,” I sometimes answer by telling a story.

Let us imagine, I say to the people in the room or the auditorium in

which I am speaking, that the entrance door is thrust open and a

young man bursts in, breathless from running and obviously agitated,

who ignores the proceedings and just shouts, “You wouldn’t believe

what happened to me!”

He then goes on to relate that he was out in

the countryside hiking, that it was getting dark and he was tired,

that he found some stones and put his knapsack on them as a cushion,

and that he fell asleep. Then he was suddenly awakened, not by a

sound but by bright lights. He looked up and saw beings going up and

down a ladder. The ladder led skyward, toward a hovering, round

object. There was a doorway in the object through which light from

inside shone out. Silhouetted against the light was the commander of

the beings. The sight was so awesome that our lad fainted. When he

came to, there was nothing to be seen. Whatever had been there was

gone.

Still excited by his experience, the young man finishes the story by

saying he was no longer sure whether what he had seen was real or

just a vision, perhaps a dream. What do we think? Do we believe him?

We should believe him if we believe the Bible, I say, because what I

had just related is the tale of Jacob’s vision as told in Genesis,

chapter 7. Though it was a vision seen in a dreamlike trance, Jacob

was certain that the sight was real, and he said,

Surely Yahweh is present in

this place, and I knew it not...

This is none other but an abode of the gods, and this is the gateway

to heaven.

I once pointed out at a conference where other speakers delved into

the subject of UFOs that there is no such thing as Unidentified

Flying Objects. They are only unidentified or unexplainable by the

viewer, but those who operate them know very well what they are.

Obviously, the hovering craft that Jacob saw was readily identified

by him as belonging to the Elohim, the plural gods. What he did not

know, the Bible makes clear, was only that the place where he had

slept was one of their lift-off pads.

The biblical tale of the heavenward ascent of the Prophet Elijah

describes the vehicle as a Fiery Chariot. And the

Prophet Ezekiel,

in his well-documented vision, spoke of a celestial or airborne

vehicle that operated as a whirlwind and could land on four wheeled

legs.

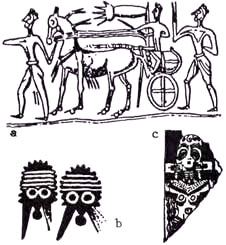

Ancient depictions and terminology show that a distinction was made

even then between the different kinds of flying machines and their

pilots. There were the rocketships (Fig. 98a) that served as shuttle

craft and the orbiters, and we have already seen what the Anunnaki

astronauts and the orbiting Igigi looked like. And there were the

“whirlbirds” or “sky chambers” that we now call VTOLs (Vertical

Take-Off and Landing aircraft) and helicopters; how these looked in

antiquity is depicted in a mural at a site on the east side of the

Jordan, near the place from which Elijah was carried heavenward

(Fig. 98b). The goddess Inanna/Ishtar liked to pilot her own “sky

chamber,” at which time she would be dressed like a World War I

pilot (Fig. 98c).

Figure 98

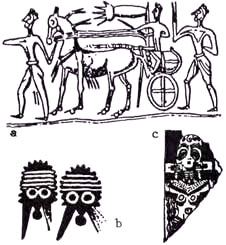

But other depictions were also found—clay figurines of human-looking

beings with elliptical heads and large, slanting eyes

|

Figure 99

|

(Fig. 99)—an

unusual feature of whom was their bisexuality (or lack of it): their

lower parts depicted the male member overlaid or dissected by the

opening of a female vagina.

Now, as one looks at the drawings of the “humanoids” by

those who claim to have seen the occupants of UFOs, it is

obvious they do not look like us—which means they do not look like

the Anunnaki. Rather, they look like the odd humanoids depicted by

the ancient figurines.

This similarity may hold an important clue to the identity of the

small creatures with smooth skins, no sex organs, no hair,

elliptical heads, and large odd eyes that are supposed to be

operating the purported UFOs. If the tales be true, then what the

“contactees” have seen are not the people, the intelligent beings,

from another planet—but their anthropoid robots.

And if even a tiny percentage of the reported sightings is true,

then the relatively large number of alien craft visiting Earth in

recent times suggests that they could not possibly come, in such

profusion and frequency, from a distant planet. If they come, they

must come from somewhere relatively close by.

And the only plausible candidate is Mars—and its moonlet Phobos.

The reasons

for the use of Mars as a jumping-off base for spacemen’s visits to

Earth should be clear by now. The evidence for my suggestion that

Mars had served in the past as a space base for the Anunnaki has

been presented. The circumstances in which Phobos 2 was lost

indicate that someone is back there on Mars—someone ready to destroy

what to them is an “alien” spacecraft. How does Phobos, the moonlet,

fit into all this?

Simply put, it tits very well.

To understand why, we ought to backtrack and list the reasons for

the 1989 mission to Phobos. At present Mars has two tiny satellites

named Phobos and Deimos. Both are believed to be not original moons

of Mars but asteroids that were captured into Mars orbit. They are

of the carbonaceous type (see the discussion of asteroids in

chapter

4) and therefore contain water in substantial amounts, mostly in the

form of ice just under the moonlets’ surfaces. It has been proposed

that with the aid of solar batteries or a small nuclear generator,

the ice could be melted to obtain water.

The water could then be separated into oxygen and hydrogen, for breathing

and as fuel. The hydrogen could also be combined with the moonlets”

carbon to make hydrocarbons. As do other asteroids and comets, these planetisimals contain nitrogen, ammonia, and other organic

molecules. All in all, the moonlets could become self-supporting

space bases, the gift of nature.

Deimos would be less convenient for such a purpose. It is only nine

by eight by seven miles in size and orbits some 15,000 miles away

from Mars. The much larger Phobos (seventeen by thirteen by twelve

miles) is only some 5,800 miles away from Mars—a short hop for a

shuttlecraft or transporter from one to the other. Because Phobos

(as does Deimos too) orbits Mars in the equatorial plane, Phobos can

be observed from Mars (or observe goings on upon Mars), between the

sixty fifth parallels north and south—a band that includes all the

unusual and artificial-looking features on Mars except “ Inca City.”

Moreover, because of its proximity, Phobos completes about 3.5

orbits around Mars in a single Martian day—an almost constant

presence.

Further recommending Phobos as a natural orbiting station around

Mars is its minuscule gravity, compared with that of Earth and even

of Mars. The power required for take-off from Phobos is no greater

than that required to develop an escape velocity of fifteen miles an

hour; conversely, very little power is needed to brake for a landing

on it.

These are the reasons the two Soviet spacecraft, Phobos 1 and 2,

were sent there. It was an open secret that the mission was a

scouting expedition for the intended landing of a “robotic rover” on

Mars in 1994 and the launching of a manned mission to Mars after

that, with a view to establishing a base thereon within the

following decade. Prearrival briefings at mission control in Moscow

revealed that the spacecraft carried equipment to locate “the

heat-emitting areas on Mars” and to obtain “a better idea of what

kind of life exists on Mars.” Although the provision, “if any,” was

quickly added, the plan to scan both Mars and Phobos not only with

infrared equipment but also with gamma-ray detectors hinted at a

very purposeful search.

After scanning Mars the two spacecraft were to turn their attention

entirely to Phobos. It was to be probed by radar as well as by the

infrared and gamma-ray scanners and was to be photographed by three television cameras.

Apart from such orbital scanning, the spacecraft were to drop two

types of landers to the surface of Phobos:

-

one, a stationary device

that would have anchored itself to the surface and transmitted data

over the long term

-

the other, a “hopper” device with springy legs

that was meant to hop and skip about the moonlet and report its

findings from all over it

There were still other experiments in the bag of tricks of Phobos 2.

It was equipped with an ion emitter and a laser gun that were to

shoot their beams at the moonlet, stir up its surface dust,

pulverize some of the surface material, and enable equipment aboard

the spacecraft to analyze the resultant cloud. At that point the

spacecraft was to hover a mere 150 feet above Phobos, and its

cameras were to photograph features as small as six inches.

What exactly were the mission planners expecting to discover at such

close range? It must have been an important objective, because it

later transpired that the “individual scientists” from the United

States who were involved in the mission’s planning and equipping

included Americans with experience in Mars research whose roles were

officially sanctioned by the United States government within the

framework of the improvement in U.S.-Soviet relations.

Also, NASA

had put at the mission’s disposal its Deep Space Network of radio

telescopes which has been involved not only in satellite

communications but also in the Search for Extraterrestrial

Intelligence (SETI) programs; and scientists at the JPL in Pasadena,

California, were helping track the Phobos spacecraft and monitor

their data transmissions. It also became known that the British

scientists who were participating in the project were in fact

assigned to the mission by the British National Space Centre.

With the French participation, guided by its National Space Agency

in Toulouse; the input by West Germany’s prestigious Max Planck

Institute; and the scientific contributions from a dozen other

European nations, the Phobos Mission was nothing short of a

concerted effort by modern science to lift the veil from Mars and

enlist it in Mankind’s course on the road to Space.

But was someone there, at Mars, who did not welcome this intrusion?

It is noteworthy that Phobos, unlike the

smaller and smooth surfaced Deimos, has peculiar features that have

led some scientists in the past to suspect that it was artificially

fashioned. There are peculiar “track marks” (Fig. 100) that run

almost straight and parallel to each other.

Figure 100

Their width is almost

uniform, some 700 to 1,000 feet, and their depth, too. is a uniform

75 to 90 feet (as far as could be measured from the Viking

orbiters). The possibility that these “’trenches,” or tracks, were

caused by flowing water or by wind has been ruled out, since neither

exist on Phobos. The tracks seem to lead to or from a crater that

covers more than a third of the moonlet’s diameter and whose rim is

so perfectly circular that it looks artificial (see Fig. 94

above).

What are these tracks or trenches, how did they come about, why do

they emanate from the circular crater, and does the crater lead into

the moonlet’s interior? Soviet scientists have thought that there

was something artificial about Phobos in general, because its almost

perfect circular orbit around Mars at such proximity to the planet

defies the laws of celestial motion: Phobos, and to some extent

Deimos, too, should have elliptical orbits that would have either

thrown them off into space or made them crash into Mars a long time

ago.

The implication that Phobos and Deimos might have been placed

in Mars orbit artificially by “someone” seemed preposterous. In

fact, however, the capture of asteroids and towing them to where

they would stay in Earth orbit has been deemed a technologically

achievable feat; so much so that such a plan was presented at the

Third Annual Space Development Conference held in San Francisco in

1984.

Richard Gertsch of the Colorado School of Mines, one of

several presenters of the plan, pointed out that,

“a startling

variety of materials exist” out in space;

“asteroids are

particularly rich in strategic minerals such as chromium, germanium

and gallium.”

“I believe that we have identified asteroids that are

accessible and could be exploited,” stated another presenter,

Eleanor F. Helin of JPL.

Have others, long ago, carried out ideas and plans that modern

science envisions for the future—bringing Phobos and Deimos, two

captured asteroids, into orbit around Mars to burrow into their

interiors?

In the 1960s it was noticed that Phobos was speeding up its orbit around Mars;

this led Soviet scientists to suggest that Phobos was lighter than

its size warrants. The Soviet physicist I. S. Shklovsky then offered

the astounding hypothesis that Phobos was hollow.

Other Soviet writers then speculated that Phobos was an,

“artificial

satellite” put into Mars orbit by “an extinct race of humanoids

millions of years ago.”

Others ridiculed the idea of a hollow

satellite and suggested that Phobos was accelerating because it is

drifting closer to Mars. The detailed report in Nature now includes

the finding that Phobos is even less dense than has been thought, so

that its interior is either made of ice or is hollow.

Were a natural crater and interior faults artificially enlarged and

carved out by “someone” to create inside Phobos a shelter, shielding

its occupants from the cold and radiation of space? The Soviet

report does not speculate on that; but what it says regarding the

“tracks” is illuminating. It calls them “grooves,” reports that

their sides are of a brighter material than the moonlet’s surface,

and, what is indeed a revelation, that in the area west of the large

crater, “new grooves can be identified”—grooves or tracks that were

not there when Mariner 9 and the Vikings took pictures of the

moonlet.

Since there is no volcanic activity on Phobos (the crater

in its natural shape resulted from meteorite impacts, not

volcanism), no wind storms, no rain, no flowing water—how did the

new grooved tracks come about? Who was there on Phobos (and thus on

Mars) since the 1970s? Who is on it now? For, if there is no one

there now, how to explain the March 27, 1989, incident?

The chilling possibility that modern science, catching up with

ancient knowledge, has brought Mankind to the first incident in a

War of the Worlds, rekindles a situation that has lain dormant

almost 5,500 years.

The event that parallels today’s situation has come to be known as

the Incident of the Tower of Babel. It is described in Genesis,

chapter 11, and in The Wars of Gods and Men I refer to Mesopotamian

texts with earlier and more detailed accounts of the incident. I

have placed it in 3450 B.C. and construed it as the first attempt by

Marduk to establish a space base in Babylon as an act of defiance

against Enlil and his sons.

In the biblical version, the people whom Marduk had gotten

to do the job were building, in Babylon, a city with a “tower

whose head shall reach the heaven” in which a Shem—a space

rocket—was to be installed (quite possibly in the manner depicted

on a coin from Byblos (see Fig. 101). But the other

deities were not amused by this foray of Mankind into the

space age; so

Yahweh came down to see the city

and the tower which the humans were building.

And he said to unnamed colleagues:

This is just the beginning of their undertakings;

From now on, anything that they shall scheme to do shall no longer

be impossible for them.

Figure 101

Come, let us go down and confuse their language so that they should

not understand each other’s speech. Almost 5,500 years later, the

humans got together and “spoke one language,” in a coordinated

international mission to Mars and Phobos.

And, once again, someone was not amused.

Back to Contents

Back to Phobos - A Strange "Thing"...

|