|

The Landing Place

The greatest Roman temple ruins lie not in Rome, but in the

mountains of Lebanon. They encompass a grand temple to Jupiter—the

grandest built anywhere in antiquity to honor any one God. Many

Roman rulers, over a period of some four centuries, toiled to

glorify this remote and alien place and erect its monumental

structures. Emperors and generals came to it in search of oracles,

to find out their fate. Roman legionnaires sought to be billeted

near it; the devout and the curious went to see it with their own

eyes: it was one of the wonders of the ancient world.

Daring European travelers, risking life and limb, reported the

existence of the ruins since the visit there by Martin Raumgarten in

January 1508. In 1751, the traveler Robert Wood, accompanied by the

artist James Dawkins, restored some of the place's ancient fame when

they described it in words and sketches.

"When we compare the ruins

... with those of many cities we visited in Italy, Greece, Egypt

and other parts of Asia, we cannot help thinking them the remains of

the boldest plan we ever saw attempted in architecture"—bolder in

certain aspects than even the great pyramids of Egypt.

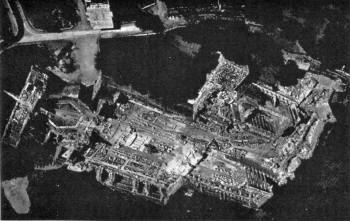

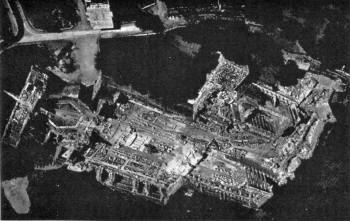

The view upon

which Wood and his companion had come was a panorama in which the

mountaintop, the temples and the skies blended into one (Fig. 90).

Fig. 90

The site is in the mountains of Lebanon, where they part to form a

fertile, flat valley between the "Lebanon" range to the west and the

"Anti-Lebanon" range to the east; where two rivers known from

antiquity, the Litani and the Orontes, begin to flow into the

Mediterranean Sea. The ruins were of imposing Roman temples that

were erected upon a vast horizontal platform, artificially created

at about 4,000 feet above sea level. The sacred precinct was

surrounded by a wall, which served both as a retaining wall to hold

the earthworks forming the flat top, as well as a fence to protect

and screen off the area. The enclosed squarish area, with some sides

almost 2,500 feet long, measured over five million square feet.

Situated so as to command the flanking mountains and the approaches

to the valley from north and south, the sacred area had its

northwestern corner deliberately cut off—as seen in this

contemporary bird's eye view (Fig. 91a).

The right-angled cutout created an oblong area, which extended the

platform's unimpeded northern view westward. It was at that

specially conceived corner that the vastest-ever temple to Jupiter

stood high, with some of the tallest (65 feet) and largest (7.5 feet

in diameter) columns known in antiquity. These columns supported an

elaborately decorated superstructure ("architrave") 16 feet in

height, atop which there was a slanting roof, further raising the

temple's pinnacle.

The temple proper was only the westernmost (and oldest) part of a

four-part shrine to Jupiter, which the Romans are believed to have

started to build soon after they occupied the place in 63 B.C.

Fig. 91

Arranged along a slightly slanted east-west axis (Fig. 91b) were,

first, a monumental Gateway ("A"); it comprised a grand staircase

and a raised portico supported by twelve columns, in which there

were twelve niches to hold the twelve Olympian Gods. The worshippers

then entered a forecourt ("B") of an hexagonal design, unique in

Roman architecture; and through it continued to a vast altar court

("C"), which was dominated by an altar of monumental proportions: it

rose some 60 feet from a base of about 70 by 70 feet.

At the western

end of the court stood the God's house proper ("D"). Measuring a

colossal 300 by 175 feet, it stood upon a podium which was itself

raised some 16 feet above the level of the court—a total of 42 feet

above the level of the base platform. It was from that extra height

that the tall columns, the architrave and the roof made together a

real ancient skyscraper.

From its monumental gateway staircase to its final western wall, the

shrine extended for more than 1,000 feet in length. It completely

dwarfed a very large temple to its south ("E"), which was dedicated

to a male deity, some think Bacchus but probably Mercury; and a

small round temple ("F") to the southeast, where Venus was

venerated.

A German archaeological team that explored the site and

studied its history on orders of Kaiser Wilhelm II, soon after he

had visited the place in 1897, was able to reconstruct the layout of

the sacred precinct and prepared an artist's

rendering of what the ancient complex of temples, stairways,

porticoes, gateways, columns, courtyards and altars probably looked

like in Roman times (Fig. 92).

Fig. 92

A comparison with the renowned Acropolis of Athens will give one a

good idea of the scale of this Lebanese platform and its temples.

The Athens complex (Fig. 93) is situated upon a stepped ship-like

terrace less than 1,000 feet at its longest and about 400 feet at

its widest.

The stunning Parthenon (temple of Athena) which still

dominates the once sacred area and the whole plain of Athens is

about 230 by 100 feet—even smaller than the temple of

Mercury/Bacchus at the Lebanese Site.

Fig. 93

Having visited the ruins, the archaeologist and architect Sir

Mortimer Wheeler wrote two decades ago:

"The temples ... owe

nothing of their quality to such new-fangled aids as concrete. They

stand passively upon the largest known stones in the world, and some

of their columns are the tallest from antiquity... . Here we have

the last great monument ... of the Hellenic world."

Hellenic world indeed, for there is no reason that any historian or

archaeologist could find for this gigantic effort by the Romans, in

an out-of-the-way place in an unimportant province, except for the

fact that the place was hallowed by the Greeks who had preceded

them. The Gods to whom the three temples were dedicated—Jupiter,

Venus and Mercury (or Bacchus)—were the Greek Gods Zeus, his sister

Aphrodite and his son Hermes (or Dionysus).

The Romans considered the site and its great temple as the ultimate

attestations of the almightiness and supremacy of Jupiter. Calling

him love (echo of the Hebrew Yehovah?), they inscribed upon the

temple and its main statue the divine initials I.O.M.H.—the legend

standing for Iove Optimus Maximus Heliopolitanus: the Optimal and

Maximal Jupiter the Heliopolitan.

The latter title of Jupiter stemmed from the fact that though the

great temple was dedicated to the Supreme God, the place itself was

considered to have been a resting place of Helios, the Sun God who

could traverse the skies in his swift chariot. The belief was

transmitted to the Romans by the Greeks, from whom they also adopted

the name of the place: Heliopolis. How the Greeks had come to so

name the place, no one knows for sure; some suggest that it was so

named by Alexander the Great.

Yet Greek veneration of the place must have been older and deeper

rooted, for it made the Romans glorify the place with the greatest

of monuments, and seek there the oracle's word concerning their

fate. How else to explain the fact that, "in terms of sheer acreage,

weight of stone, dimensions of the individual blocks, and the amount

of carving, this precinct can scarcely have had a rival in the

Graeco-Roman world" (John M. Cook, The Greeks in Ionia and the

East).

In fact, the place and its association with certain Gods go back to

even earlier times. Archaeologists believe that there may have been

as many as

six temples built on the site before Roman times; and it is certain

that whatever shrines the Greeks may have erected there, they—as the

Romans after them—were only raising the structures atop earlier

foundations, religiously and literally.

Zeus (Jupiter to the

Romans), it will be recalled, arrived in Crete from Phoenicia

(today's Lebanon), swimming across the Mediterranean Sea after he

had abducted the beautiful daughter of the king of Tyre. Aphrodite

too came to Greece from western Asia. And the wandering Dionysus, to

whom the second temple (or perhaps another) was dedicated, brought

the vine and winemaking to Greece from the same lands of western

Asia.

Aware of the worship's earlier roots, the Roman historian Macrobius

enlightened his countrymen in the following words (Saturnalia I,

Chapter 23):

The Assyrians too worship the sun under the name of Jupiter, Zeus

Helioupolites as they call him, with important rites in the city of

Heliopolis... .

That this divinity is at once Jupiter and the Sun is manifest both

from

the nature of its ritual and from its outward appearance... .

To prevent any argument from ranging through a whole list of

divinities, I will explain what the Assyrians believe concerning the

power

of the sun (God). They have given the name Adad to the God whom they

venerate as highest and greatest... .

The hold the place had over the beliefs and imagination of people

throughout the millennia also manifested itself in the history of

the place following its Roman veneration. When Macrobius wrote the

above, circa

A.D. 400, Rome was already Christian and the site was already a

target of zealous destruction.

No sooner did Constantine the Great

(A.D. 306-337) convert to Christianity, than he stopped all

additional work there and instead began the conversion of the place

into a Christian shrine. In the year 440, according to one

chronicler,

"Theodosius destroyed the temples of the Greeks; he

transformed into a Christian church the temple of Heliopolis, that

of Ba'al Helios, the great Sun-Baal of the celebrated Trilithon."

Justinian (525-565) apparently carried off some of the pillars of

red granite to Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, to build there

the church of Hagia Sophia. These efforts to Christianize the place

encountered repeated armed opposition by the local populace.

When the Muslims gained the area in the year 637, they converted the

Roman temples and Christian churches atop the huge platform into a

Muhammedan enclave. Where Zeus and Jupiter had been worshiped, a

mosque was built to worship Allah.

Modern scholars have tried to shed more light on the age-long

worship at this place by studying the archaeological evidence from

neighboring sites. A principal one of these is Palmyra (the biblical

Tadmor), an ancient caravan

center on the way from Damascus to Mesopotamia. As a result, such

scholars as Henry Seyrig (La Triade Heliopolitaine) and

Rene Dussaud

(Temples et Cultes Heliopolitaine) have concluded that a basic triad

had been worshipped throughout the ages. It was headed by the God of

the Thunderbolt and included the Warrior Maiden and the Celestial

Charioteer.

They and other scholars helped establish the now

generally accepted conclusion, that the Roman-Greek triad stemmed

from the earlier Semitic beliefs, which in turn were based upon the

Sumerian pantheon. The earliest Triad was headed, it appears, by Adad, who was allotted by his father

Enlil—the chief God of

Sumer—"the mountainlands of the north." The female member of the

Triad was Ishtar.

After he visited the area, Alexander the Great

struck a coin honoring Ishtar/Astarte and Adad; the coin bears his

name in Phoenician-Hebrew script (Fig. 94). The third member of the

Triad was the Celestial Charioteer, Shamash—commander of the

prehistoric astronauts. The Greeks honored him (as Helios) by

erecting a colossal statue atop the main temple (see Fig. 92),

showing him driving his chariot.

Fig. 94

To them, its swiftness was denoted by the four

horses that pulled it; the authors of the Book of Enoch knew better:

"The chariot of Shamash," it says, "was driven by the wind."

Examining the Roman and Greek traditions and beliefs, we have

arrived back at Sumer; we have circled back to Gilgamesh and his

Search for Immortality in the Cedar Forest, at the "crossroads of

Ishtar." Though in the territory of Adad, he was told, the place was

also within the jurisdiction of Shamash. And so we have the original

Triad: Adad, Ishtar, Shamash.

Have we come upon the Landing Place?

That the Greeks were aware of the epic adventures of Gilgamesh, few

scholars nowadays doubt. In their "investigation of the origins of

human knowledge and its transmission through Myth," entitled

Hamlet's Mill, Giorgio de Santillana and

Hertha von Deschend point

out that "Alexander was a true replica of Gilgamesh." But even

earlier, in the historic tales of Homer, the heroic Odysseus had

already followed similar footsteps. Shipwrecked after traveling to

the abode of Hades in the Lower World, his

men reached a place where they "ate the cattle of the Sun God" and

were therefore killed by Zeus.

Left alive alone, Odysseus wandered

about until he reached the "Ogygian island"—the secluded place from

pre-Deluge times. There, the Goddess Calypso, "who kept him in a

cave and fed him, wanted him to marry her; in which case she

intended making him immortal, so that he should never grow old." But

Odysseus refused her advances— just as Gilgamesh had turned down

Ishtar's offer of love.

Henry Seyrig, who as Director of Antiquities of Syria devoted a

lifetime to the study of the vast platform and its meaning, found

that the Greeks used to conduct there "rites of mystery, in which

Afterlife was represented as human Immortality—an identification

with the deity obtained by the ascent (heavenward) of the soul." The

Greeks, he concluded, indeed associated this place with Man's

efforts to attain Immortality.

Was then this place the very place in the Cedar Mountains to which

Gilgamesh had first gone with Enkidu, the Crest of Zaphon of Ba'al?

To give a definite answer, let us look more closely at the physical

features of the place. We will find that the Romans and Greeks have

built their temples upon a paved platform which existed from much

earlier times—a platform constructed of large, thick stone blocks so

tightly put together that no one—to this very day—has been able to

penetrate it and study the chambers, tunnels, caverns and other

substructures that lie hidden beneath it.

That such subterranean structures undoubtedly exist is judged not

only from the fact that other Greek temples had secret, subterranean

cellars and grottoes beneath their apparent floors. Georg Ebers and

Hermann Guthe (Palastina in Bild und Wort, the English version is

titled Picturesque Palestine) reported a century ago that the local

Arabs entered the ruins "at the southeast corner, through a long

vaulted passage like a railway tunnel under the great platform"

(Fig. 95).

Fig. 95

"Two of these great vaults run parallel with each other,

from east to west, and are connected by a third running at right

angles to them from north to south."

As soon as they entered the

tunnel, they were caught in total darkness, broken here and there by

eerie green lights from puzzling "laced windows." Emerging from the

460-feet-long tunnel, they found themselves under the north wall of

the Sun Temple, "which the Arabs call Dar-as-saadi—House of Supreme

Blissful-ness."

The German archaeologists also reported that the platform apparently

rested upon gigantic vaults; but they concerned themselves with

mapping and reconstructing the superstructure. A French

archaeological mission, led by Andre Parrot in the 1920s, confirmed

the existence of the subterranean maze, but was unable to penetrate

its hidden parts. When the platform was pierced from above through

its thick stones, evidence was found of structures beneath it.

The temples were erected upon a platform raised to thirty feet,

depending on the terrain. It was paved with stones whose size, to

judge by

the slabs visible at the edges, ranged from a length of twelve feet

to thirty feet, a frequent width of nine feet and a thickness of six

feet. No one has yet attempted to calculate the quantity of stone

hewn, cut, shaped, hauled and imbedded layer upon layer upon this

site; it could possibly dwarf the Great Pyramid of Egypt.

Whoever laid this platform originally, paid particular attention to

the rectangular northwestern corner, the location of the temple of

Jupiter/Zeus. There, the temple's more than 50,000 square feet

rested upon a raised podium which was certainly intended to support

some extremely heavy weight. Constructed of layer upon layer of huge

stones, the Podium rose twenty-six feet above the level of the Court

in front of it and forty-two feet above the ground on its exposed

northern and western sides.

On the southern side, where six of the

temple's columns still stand, one can clearly see (Fig. 96a) the

stone layers: interspersed between sizable yet relatively

small stones, there are alternating rows of stone blocks measuring

up to twenty-one feet in length. One can also see (bottom left) the

lower layers of the Podium, protruding as a terrace below the raised

temple. There, the stones are even more gigantic.

Fig. 96

More massive by far were the stone blocks in the western side of the

Podium. As shown in the schematic drawing of the northwestern corner

prepared by the German archaeological team (Fig. 96b), the

protruding base and the top layers of the Podium were constructed of

"cyclopian" stone blocks some of which measure over thirty-one feet

in length, about thirteen feet in height and are twelve feet thick.

Each such slab represents thus about 5,000 cubic feet of stone and

weighs more than 500 tons.

Large as these stones are—the largest ones in the Great Pyramid of

Egypt weigh 200 tons—they were not the largest slabs of granite

employed by the ancient master builder in creating the Podium.

The central layer—situated some twenty feet above the base of the

Podium—was incredibly made up of even larger stones. Modern

surveyors have spoken of them as "giant," "colossal," "huge."

Ancient historians named them the Trilithon—the Marvel of the Three

Stones. For there, exposed to view in the western side of the

Podium, lie side by side three stone blocks, the likes of which

cannot be seen anywhere else in the world.

Precisely shaped and

perfectly fitting, each of the three stones (Fig. 97) measures over

sixty feet in length, with sides of fourteen and twelve feet. Each

slab thus represents more than 10,000 cubic feet of granite and

weighs well over 1,000 tons!

Fig. 97

The stones for the Platform and

Podium were quarried locally; Wood

and Dawkins include one of these quarries (Fig. 90) in their

panoramic sketch, showing some of the large stone blocks strewn

around in the ancient quarry. But the gigantic blocks were hewn, cut

and shaped at another quarry, situated in the valley some

three-quarters of a mile southwest of the sacred precinct. It is

there that one comes upon a sight even more incredible than that of

the Trilithon.

Partly buried in the ground, there lies yet another one of the

colossal granite slabs—left in situ by whoever the grand quarrier

was. Fully shaped and perfectly cut, with only a thin line at its

base still connecting it to the rocky ground, it is an unbelievable

sixty-nine feet long and has a girth of sixteen by fourteen feet. A

person climbing upon it (Fig. 98) looks like a fly upon a block of

ice.... It weighs, by conservative estimates, more than 1,200 tons.

Fig. 98

Most scholars believe that it was intended to be hauled, as its

three sisters were, up to the sacred precinct and perhaps be used to

extend the terrace-part of the Podium on the northern side. Ebers

and Guthe record a theory that in the row beneath the Trilithon,

there are not two smaller slabs but a single stone akin to the one

found at the quarry, measuring more than sixty-seven feet in length,

but either damaged or otherwise chiseled to give the appearance of

two side-by-side stones.

Wherever the leftover colossal stone was intended to be placed, it

serves as a mute witness to the immensity and uniqueness of the

Platform and Podium nesting in the mountains of Lebanon. The

mind-boggling fact is that even nowadays there exists no crane,

vehicle or mechanism that can lift such a weight of 1,000-1,200

tons—to say nothing of carrying such an immense object over valley

and mountainside, and placing each slab in its precise position,

many feet above the ground. There are no traces of any roadway,

causeway, ramp or other earthworks that could even remotely

suggest the hauling or dragging of these megaliths from the quarry

to their uphill site.

Yet in remote days, someone, somehow had achieved the feat... .

But who? Local traditions hold that the place had existed from the

days of Adam and his sons, who resided in the area of the Cedar

Mountains after the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of

Eden. Adam, these legends relate, inhabited the place which is now

Damascus, and died not far from there. It was Cain his son who built

a refuge upon the Cedar Crest after he had killed Abel.

The Maronite Patriarch of Lebanon related the following tradition:

"The fastness on Mount Lebanon is the most ancient building in the

world. Cain, the son of Adam, built it in the year 133 of Creation,

during a fit of raving madness. He gave it the name of his son

Enoch, and peopled it with giants who were punished for their

iniquities by the Flood."

After the Deluge, the place was rebuilt by

the biblical Nimrod, in his efforts to scale the heavens. The

Tower

of Babel, according to these legends, was not in Babylon but upon

the great platform in Lebanon.

A seventeenth-century traveler named d'Arvieux wrote in his

Memoires

(Part II, Chapter 26) that local Jewish inhabitants, as well as

Muslim residents, held that an ancient manuscript found at the site

revealed that,

"After the Flood, when Nimrod reigned over Lebanon, he

sent giants to rebuild the Fortress of Baalbek, which is so named in

honor of Ba'al, the God of the Moabites, worshippers of the

Sun-God."

The association of the God Ba'al with the place in post-Diluvial

days strikes a bell. Indeed, no sooner were the Greeks and Romans

gone than the local people abandoned the Hellenistic name Heliopolis

and resumed calling the place by its Semitic name. It is the name by

which it is still called to this day:

Baalbek.

There are differing opinions as to the precise meaning of the name.

Many believe that it means "The Valley of Ba'al." But from the

spelling and from Talmudic references, we surmise that it has meant

"The Weeping of Ba'al."

We can hear again the closing verses of the Ugaritic epic,

describing the fall of Ba'al in his struggle with Mot, the discovery

of his lifeless body, his entombment by Anat and Shepesh in a grotto

upon the Crest of Zaphon:

They came upon Baal, fallen on the ground;

Puissant Baal is dead;

The Prince, Lord of Earth, is perished... .

Anat weeps her fill of weeping;

In the valley she drinks tears like wine.

Loudly she calls unto the Gods' Torch, Shepesh:

"Lift Puissant Baal, I pray,

lift him onto me."

Hearkening, the Gods' Torch Shepesh

Picks up Puissant Baal,

Sets him on Anat's shoulder.

Up to the Fastness of Zaphon she brings him;

Bewails him, entombs

him;

Lays him in the hollows of the earth.

All these local legends, which as all legends contain a kernel of

age-old recollections of actual events, agree that the place is of

extreme antiquity. They ascribe its building to "giants" and connect

its construction with the events of the Deluge. They connect it with

Ba'al, its function being that of a "Tower of Babel"—a place from

which to "scale the heavens."

As we look at the vast Platform, its location and layout, and ponder

the purpose of the immense Podium built to sustain massive weights,

the depiction on the coin from Byblos (Fig. 89) keeps flashing

before our eyes: a great temple, a walled sacred area, a podium of

extra-strong construction— and upon it the rocket-like Flying

Chamber.

The words and descriptions of the Hidden Place in the

Epic of

Gilgamesh also keep echoing in our ears. The insurmountable wall,

the gate which stuns whoever touches it, the tunnel to the

"enclosure from which words of command are issued," the "secret

abode of the Anunnaki," the monstrous Guardian with his "radiant

beam."

And there is no doubt left in our mind that in Baalbek we have found

Ba'al's Crest of Zaphon, the target of the first journey of

Gilgamesh.

The designation of Baalbek as "the Crossroads of Ishtar" implies

that, as she roamed Earth's skies, she could come and go from that

"Landing Place" to other landing places upon Earth. Likewise, the

attempt by Ba'al to install upon the Crest of Zaphon "a contraption

that launches words, a 'stone that whispers, "' implied the

existence elsewhere of similar communication units:

"Heaven with

Earth it makes converse, and the seas with the planets."

-

Were there indeed such other places on Earth that could serve as

Landing Places for the aircraft of the Gods?

-

Were there, besides

upon the Crest of Zaphon, other "stones that whisper"?

The first obvious clue is the very name "Heliopolis," indicating the

Greek belief that Baalbek was, somehow, a "City of the sun God"

paralleling its namesake city in Egypt. The Old Testament too

recognized the existence of a northern Beth-Shemesh ("House of

Shamash") and a southern Beth-Shemesh, On, the biblical name for

the

Egyptian Heliopolis. It was, the prophet Jeremiah said, the place of

the "Houses of the Gods of Egypt," the location of Egypt's obelisks.

The northern Beth-Shemesh was in Lebanon, not far from Beth-Anath

("House/Home of Anat"); the prophet Amos identified it as the

location of the "palaces of Adad ... the House of the one who saw

El." During the reign of Solomon, his domains encompassed large

parts of Syria and Lebanon, and the list of places where he had

built great structures included Baalat ("The Place of Ba'al") and

Tamar ("The Place of Palms"); most

scholars identify these places as Baalhek and Palmyra (see map, Fig.

78).

Greek and Roman historians made many references to the links that

connected the two Heliopolises. Explaining the Egyptian pantheon of

twelve Gods to his countrymen, the Greek historian Herodotus also

wrote of an "Immortal whom the Egyptians venerated as Hercules." He

traced the origins of the worship of this Immortal to Phoenicia,

"hearing that there was a temple of Hercules at that place, very

highly venerated." In the temple he saw two pillars.

"One was of

pure gold; the other was of emerald, shining with great brilliancy

at night."

Such sacred "Sun Pillars"—"Stones of the Gods"—were actually

depicted on Phoenician coins following the area's conquest by

Alexander (Fig, 99). Herodotus provides us with the additional

information that of the two connected stones, one was made of the

metal which is the best conductor of electricity (gold); and the

other of a precious stone (emerald) as is now used for laser

communications, giving off an eerie radiance as it emits a

high-powered beam. Was it not like the contraption set up by Ba'al,

which the Canaanite text described as "stones of splendor?"

Fig, 99

The Roman historian Macrobius, writing explicitly about the

connection between the Phoenician Heliopolis (Baalbek) and its

Egyptian counterpart, also mentions a sacred stone; according to

him, "an object" venerating the Sun God Zeus Helioupolites was

carried by Egyptian priests from the Egyptian Heliopolis to

Heliopolis (Baalbek) in the north.

"The object," he added, "is now

worshipped with Assyrian rather than Egyptian rites."

Other Roman historians also stressed that the "sacred stones"

worshiped by the "Assyrians" and the Egyptians were of a conical

shape. Quintus Curtius recorded that such an object was located at

the temple of Ammon at the oasis of Siwa.

"The thing which is

worshipped there as a God," Quintus Curtius wrote, "has not the

shape that artificers have usually applied to the Gods. Rather, its

appearance is most like an umbilicus, and it is made of an emerald

and gems cemented together."

The information regarding the conical object worshiped at

Siwa was

quoted by F. L. Griffith in connection with the announcement, in

The

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (1916), of the discovery of a

conical "omphalos" at the Nubian "pyramid city" of Napata. This

"unique Meroitic monument" (Fig. 100) was found by George A. Reisner

of Harvard University at the inner sanctum of the temple of Ammon

there—the southernmost temple to this God of Egypt.

Fig. 100

The term omphalos in Greek or umbilicus in Latin means a "navel"—a

conical stone which, for reasons that scholars do not understand,

was deemed in antiquity to have marked a "center of the Earth.

The temple of Ammon at the oasis of Siwa, it will be recalled, was

the location of the oracle which Alexander rushed to consult on his

arrival in Egypt. We have the testimony of both Callisthenes,

Alexander's historian, and the Roman Quintus Curtius that an

omphalos made of precious stones was the very "object" venerated at

that oracle site. The Nubian temple of

Ammon where Reisner discovered the omphalos stone was at Napata, an

ancient capital of the domains of Nubian queens; and we recall the

baffling visit of Alexander to Queen Candace, in his continuing

quest for Immortality.

Was it mere coincidence that, in his search for the secrets of

longevity, the Persian king Cambyses (as Herodotus has reported)

sent his men to Nubia, to the temple where the "Table of the Sun"

was enshrined? Early in the first millennium B.C. a Nubian queen

—the Queen of Sheba —made a long journey to King Solomon in

Jerusalem. The legends current at Baalbek relate that he embellished

the site in Lebanon in her honor. Did she then undertake the long

and hazardous voyage merely to enjoy the wisdom of Solomon, or was

her real purpose to consult the oracle at Baalbek—the biblical

"House of Shemesh?"

There seem to be more than just coincidences here; and the question

that comes to mind is this: if at all these oracle centers an

omphalos was enshrined—was the omphalos itself the very source of

the oracles?

The construction (or reconstruction) upon the Crest of Zaphon of a

launching silo and a landing platform for Ba'al was not the cause of

his fatal battle with Mot. Rather, it was his clandestine attempt to

set up a "Stone of Splendor." This device could communicate with the

heavens as well as with other places on Earth.

But, in addition, it

was,

A stone that whispers;

Men its messages will not know,

Earth's

multitudes will not comprehend.

As we ponder the apparent dual function of the

Stone of Splendor,

the secret message of Ba'al to Anat all of a sudden becomes clear:

the same device which the Gods used to communicate with each other

was also the object from which there emanated the Gods' oracular

answers to the kings and heroes!

In a most thorough study on the subject, Wilhelm H. Roscher

(Omphalos) showed that the Indo-European term for these oracle

stones— navel in English, nabel in German, etc.—stem from the

Sanskrit nabh, which meant "emanate forcefully.'' It is no

coincidence that in the Semitic languages naboh meant to foretell

and nabih meant "prophet." All these identical meanings undoubtedly

harken back to the Sumerian, in which NA.BA(R) meant "bright-shiny

stone that solves."

A veritable network of such oracle sites emerges as we study ancient

writings. Herodotus—who accurately reported (Book II, 29) the

existence of the Meroitic oracle of Jupiter-Ammon—added to the links

we have so far discussed by stating that the "Phoenicians," who

established the oracle at Siwa, also established the oldest oracle

center in Greece, the one at Dodona —a mountain site in northwestern

Greece (near the present Albanian border).

To that effect, he related a report he had heard when he visited

Egypt, whereby,

"two sacred women were once carried off from Thebes

(in Egypt) by the Phoenicians ... one of them was sold into Libya

(western Egypt) and the other into Greece. These women were the

first founders of the oracles in the two countries."

This version,

Herodotus wrote, he heard from the Egyptian priests of Thebes. But

at Dodona, the version was that "two black doves flew away from the

Egyptian Thebes," one alighting at Dodona and the other at Siwa:

whereupon an oracle of Jupiter was established at both places, the

Greeks calling him Zeus at Dodona and the Egyptians Ammon at Siwa.

The Roman historian Silicus Italicus (first century A.D.), relating

that Hannibal consulted the oracle at Siwa regarding his wars

against Rome, also credited the flight of the two doves from Thebes

with the establishment of the oracles in the Libyan desert (Siwa)

and in Greek Chaonia (Dodona). Several centuries later, the Greek

poet Nonnos, in his master work Dionysiaca, described the oracle

shrines at Siwa and Dodona as twin sites, and held that the two were

in voice communication with each other:

Behold the new-found answering voice

of the Libyan Zeus!

The thirsty

sands an oracular sent forth

to the dove at Chaonia [= Dodona].

As far as F. L. Griffith was concerned, the discovery of the

omphalos in Nubia brought to mind another oracle center in Greece.

The conical shape of the Nubian omphalos, he wrote, "was precisely

that of the omphalos at the oracle at Delphi."

Delphi, the site of Greece's most famous oracle, was dedicated to

Apollo ("He of Stone"); its ruins are still one of Greece's leading

tourist attractions. There too, as at Baalbek, the sacred precinct

consisted of a platform shaped upon a mountainside, also facing a

valley that opens up as a funnel toward the Mediterranean Sea and

the lands on its other shores.

Many records establish that an omphalos stone was Delphi's holiest

object. It was set into a special base in the inner sanctum of the

temple of Apollo, some say next to a golden statue of the God and

some say it was enshrined all by itself. In a subterranean chamber,

hidden from view by the oracle seekers, the oracle priestess, in

trance-like oblivion, answered the questions of kings and heroes by

uttering enigmatic answers—answers given by the God but emanating

from the omphalos.

The original sacred omphalos had mysteriously disappeared, perhaps

during the several sacred wars or foreign invasions which affected

the place. But a stone replica thereof, erected perhaps in Roman

times outside the temple, was discovered in archaeological

excavations and is now on display in the Delphi Museum (Fig. 101).

Fig.101

Along the Sacred Way leading up to the temple, someone, at some

unknown time, also set up a simple stone omphalos in an effort to

mark the place where oracles were first given at Delphi, before the

temple was built.

The coins of Delphi depicted Apollo seated on this omphalos (Fig.

102); and after Phoenicia fell to the Greeks, they likewise depicted

Apollo seated upon the "Assyrian" omphalos. But just as frequently,

the oracle stones were depicted as twin cones connected to each

other via a common base, as in

Fig. 99.

How was Delphi chosen as a sacred oracle place, and how did the

omphalos stone come to be there? The traditions say that when Zeus

wanted to find the center of the Earth, he released eagles from two

opposite ends of the world. Flying toward each other, they met at

Delphi; whereupon the place was marked by erecting there a navel

stone, an omphalos. According to the Greek historian Strabo, images

of two such eagles were perched on top of the omphalos at Delphi.

Fig. 102

Depictions of the omphalos have been found in Greek art, showing the

two birds atop or at the sides (Fig. 102) of the conical object.

Some scholars see in the birds not eagles, but carrier pigeons,

which—being able to find

their way back to a certain place—might have symbolized the

measuring of distances from one Center of Earth to another.

According to Greek legends, Zeus found refuge at Delphi during his

aerial battles with Typhon, resting on the platform-like area upon

which the temple to Apollo was eventually built. The shrine to Ammon

at Siwa contained not only subterranean corridors, mysterious

tunnels and secret passages inside the temple's thick walls, but

also a restricted area of some 180 by 170 feet, surrounded by a

massive wall.

In its midst, there arose a solid stone platform. We

find the same structural components, including a raised platform, in

all the sites associated with the "stones that whisper." Is one to

conclude, then, that as the far larger Baalbek was, they too were

both a Landing Place and a Communications Center?

Not surprisingly, we find the twin Sacred Stones, accompanied by the

two eagles, also depicted in Egyptian sacred writings (Fig. 103);

and many centuries before the Greeks even began to enshrine their

oracle centers, an Egyptian Pharaoh depicted an omphalos with the

two perched birds in his pyramids.

Fig.103

He was Seti I, who lived in the

fourteenth century B.C.; and it was in his depiction of the domain

of Seker, the Hidden God, that we have seen the oldest omphalos to

date—in

Fig. 19. It was the communications

means whereby messages—"words"—"were spoken to Seker every day."

In Baalbek, we have found the target of the first journey of

Gilgamesh. Having followed the threads connecting the "whispering"

Stones of Splendor, we arrived at the Duat.

It was the place where the Pharaohs sought the Stairway to Heaven

for an Afterlife. It was, we suggest, the place whereto Gilgamesh,

in search of Life, set his course on his second journey.

Back to

Stairway to Heaven

or

Back to Baalbek - A Colossal Enigma

|