|

Some time between 2200 and 2100 BC. - a time of great import at Stonehenge - Ninurta, Enlil's Foremost Son, embarked on a major undertaking: the building of a new "House" for himself at Lagash. The event throws light on many matters of Gods and men thanks to the fact that the king entrusted with the task, Gudea of Lagash, wrote it all down in great detail on two large clay cylinders.

In spite of the immensity of the task, he realized that it was a great honor and a unique opportunity to have his name and deeds remembered for all time, for not many kings were so entrusted; in fact, royal records (since found by archaeologists) spoke of at least one instance when a famous king (Naram-Sin), otherwise beloved by the Gods, was again and again refused permission to engage in the building of a new temple (such a situation arose millennia later in the case of King David in Jerusalem).

Shrewdly expressing his gratitude to his God by inscribing laudatory statements on statues of himself (Fig. 72) which Gudea then emplaced in the new temple, Gudea managed to leave behind a rather substantial amount of written information which explains the How and What for of the sacred precincts and temples of the Anunnaki.

Figure 72

As the Foremost Son of Enlil by his half sister Ninharsag and thus the heir apparent, Ninurta shared his father's rank of fifty (that of Anu being the highest, sixty, and that of Anu's other son, Enki, being forty) and so it was a simple choice to call Ninurta's ziggurat E.NINNU, the "House of Fifty." Throughout the millennia Ninurta was a faithful aide to his father, carrying out dutifully each task assigned to him.

He acquired the epithet "Foremost Warrior of Enlil" when a rebel God called Zu seized the Tablets of Destinies from Mission Control Center in Nippur, disrupting the bond Heaven-Earth; it was Ninurta who pursued the usurper to the ends of Earth, seizing him and restoring the crucial tablets to their rightful place. When a brutal war, which in The Wars of Gods and Men we have called the Second Pyramid War, broke out between the Enlilites and the Enki'ites, it was again Ninurta who led his father's side to victory.

That conflict ended with a peace conference forced on the warring clans by Ninharsag, in the aftermath of which the Earth was divided among the two brothers and their sons and civilization was granted to Mankind in the "Three Regions" - Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley. The peace that ensued lasted a long time, but not forever. One who had been unhappy with the arrangements all along was Marduk, the Firstborn Son of Enki.

Reviving the rivalry between his father and Enlil which stemmed from the complex succession rules of the Anunnaki, Marduk challenged the grant of Sumer and Akkad (what we call Mesopotamia) to the offspring of Enlil and claimed the right to a Mesopotamian city called Bab-Ili (Babylon) - literally, "Gate-way of the Gods." As a result of the ensuing conflicts, Marduk was sentenced to be buried alive inside the Great Pyramid of Giza; but, pardoned before it was too late, he was forced into exile; and once again Ninurta was called upon to help resolve the conflicts.

Ninurta, however, was not just a warrior. In the aftermath of the Deluge it was he who dammed the mountain passes to prevent more flooding in the plain between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and who had arranged extensive drainage works there to make the plain habitable again. Thereafter, he oversaw the introduction of organized agriculture to the region and was fondly nicknamed by the Sumerians Urash - "He of the Plough."

When the Anunnaki decided to give Kingship to Mankind, it was Ninurta who was assigned to organize it at the first City of Men, Kish. And when, after the upheavals caused by Marduk, the lands quieted down circa 2250 BC., it was again Ninurta who restored order and kingship from his "cult city," Lagash. His reward was permission from Enlil to build a brand new temple in Lagash. It was not that he was "homeless"; he already had a temple in Kish, and a temple within the sacred precinct in Nippur, next to his father's ziggurat.

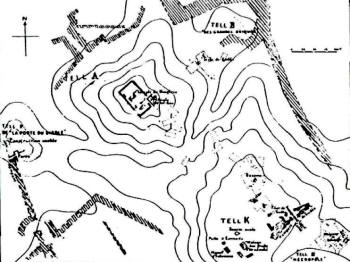

He also had his own temple in the Girsu, the sacred precinct of his "cult center," the city of Lagash. French teams of archaeologists who have been excavating at the site (now locally called Tello), conducting twenty "campaigns" between 1877 and 1933, uncovered many of the ancient remains of a square ziggurat and rectangular temples whose corners were precisely oriented to the cardinal points (Fig. 73). Figure 73

They estimated that the foundations of the earliest temple were laid in Early Dynastic times, before 2700 BC., on the mound marked "K" on the excavations map. Inscriptions by the earliest rulers of Lagash already spoke of rebuilding and improvements in the Girsu, as well as of the presentation of votive artifacts, such as the silver vase by Entemena (Fig. 48), over a period of six or seven hundred years before Gudea's time.

Some inscriptions may mean that the foundations for the very first Eninnu were laid by Mesilim, a king of Kish who had reigned circa 2850 BC. Kish, it will be recalled, was where Ninurta had established for the Sumerians the institution of Kingship. For a long time the rulers of Lagash were considered just viceroys, who had to earn the title "king of Kish" in order to be fullfledged sovereigns.

It was perhaps this second-class stigma that made Ninurta seek a temple truly authentic for his city; he also needed one that could hold the remarkable weapons that he had been granted by Anu and Enlil, including an aircraft that was nicknamed the Divine Storm Bird (Fig. 74) which had a wingspan of about seventy-five feet and thus needed a specially designed enclosure.

Figure 74

When Ninurta defeated the Enki'ites he entered the Great Pyramid and for the first time realized its intricate and amazing inner architecture in addition to its outer grandeur. The information provided by the inscriptions of Gudea suggests that Ninurta had nourished a desire to have a ziggurat of similar greatness and intricacy ever since his Egyptian tour of duty. Now that he had once again pacified Sumer and attained for Lagash the status of a royal capital, he asked Enlil once again for permission to build a new E.NINNU, a new "House of Fifty," in the Girsu precinct of Lagash.

This time, his wish was to be fulfilled. That his wish was granted should not be downplayed as a matter of course. We read, for example, in the Canaanite "myths" regarding the God Ba'al ("Lord"), that for his role in defeating the enemies of El ("The Lofty One," the supreme deity) he sought El's permission to build a House on the crest of Mount Zaphon in Lebanon.

Ba'al had sought this permission before, and was repeatedly turned down; he had repeatedly complained to "Bull El, his father":

Now he asked Asherah, El's spouse, to intercede for him; and Asherah finally convinced El to give his permission. Added to the previous arguments was a new one: Ba'al, she said, could then "observe the seasons" in his new House - make there celestial observations for a calendar.

But though a God, Ba'al could not just go ahead and build his temple-abode. The plans had to be drawn and construction supervised by the Kothar-Hasis, the "Skilled and Knowing" Craftsman of the Gods. Not only modern scholars but even Philo of Byblos in the first century a.d. (quoting earlier Phoenician historians) compared Kothar-Hasis with the Greek divine craftsman Hephaestus (who built the temple-abode of Zeus) or with Thoth, the Egyptian God of knowledge, crafts, and magic.

The Canaanite texts indeed state that Ba'al sent emissaries to Egypt to fetch KotharHasis, but found him eventually in Crete. No sooner, however, did Kothar-Hasis arrive than Ba'al got into fierce arguments with him regarding the temple's architecture. He wanted, it appears, a House of only two parts, not the customary three - an Hekhal and a Bamtim (a raised stage).

The sharpest argument was over a funnellike window or skylight which Kothar-Hasis claimed had to be positioned "in the House" but Ba'al vehemently argued should be located somewhere else. The argument is given the space of many verses in the text to show its ferocity and importance; it involved shouting and spitting... The reasons for the argument regarding the skylight and its location remain obscure; our guess is that it might have been connected with the temple's orientation.

The statement by Asherah that the temple would enable observance of the seasons suggests an orientation requiring certain astronomical observations. Ba'al, on the other hand, as the Canaanite text later reveals, was planning to install in the temple a secret communication device that would enable him to seize power over other Gods.

To that purpose Ba'al "stretched a cord, strong and supple," from the peak of Zaphon ("North") to Kadesh ("the Sacred Place") in the south, in the Sinai desert. The orientation in the end remained the way the divine architect, Kothar-Hasis, wanted it. "Thou shalt heed my words," he told Ba'al emphatically, and "as for Ba'al, his house was thus built."

If, as

one must assume, the later temples atop

the Baalbek platform were

built according to that olden plan, then we find that the

orientation Kothar-Hasis had insisted upon resulted in a temple with

an east-west axis (see Fig. 25). As the Sumerian tale of the new

Eninnu temple unfolds, we shall sec that it too involved celestial

observations to determine its orientation, and required the services

of divine architects.

All was described in detail, all was so magnificent and marvelous that, when it was finished, "the Anunnaki were altogether seized with admiration." The sections in the Gudea inscriptions of the greatest interest are those that deal with the events that preceded the construction of the temple, the determination of its orientation, its equipment and symbolism; we follow primarily the information provided in the inscription known as Cylinder A.

The chain of events, Gudea's record states, began on a certain day, a day of great significance. Referring in the inscriptions to Ninurta by his formal title NIN.GIRSU - "Lord of the Girsu" - this how the record begins:

Recording Ninurta's complaint about the delay in the building of the new temple "which is vital to the city in accordance with the ME's," it reports that on that propitious day Enlil finally granted the permission, and he also decreed what the temple's name shall be: "Its king shall name the temple E.NINNU." The edict, Gudea wrote, "made a brilliance in heaven and on Earth." Having received the permission of Enlil and having obtained the name for the new ziggurat, Ninurta was now free to proceed with the construction.

Without losing time, Gudea rushed to supplicate his God to be the one chosen for the task. Offering sacrifices of oxen and kids,

Persisting, Gudea kept praying:

Finally the miracle happened. "At midnight," he wrote, "something came to me; its meaning I did not understand." He took his asphalt-lined boat and, sailing on a canal, went to a nearby town to seek an explanation from the oracle Goddess Nanshe in her "House of Fate-Solving."

Offering prayers and sacrifices that she would solve the riddle of his vision, he proceeded to tell her about the appearance of the God whose command he was to heed:

A celestial omen then occurred whose meaning, Gudea told the oracle Goddess, he did not understand: the Sun upon Kishar, Jupiter, was suddenly seen on the horizon. A woman then appeared who gave Gudea other celestial directions:

A third divine being then appeared who had the look of a "hero":

Having heard the details of the dreamlike vision, the oracle Goddess proceeded to tell Gudea what it meant. The first God to appear was Ningirsu (Ninurta); "for thee to build his temple, Eninnu, he commanded." The heliacal rising, she explained, signaled the God Ningishzidda, indicating to him the point of the Sun on the horizon.

The Goddess was Nisaba; "to build the House in accordance with the Holy Planet she instructed thee." And the third God, Nanshe explained, "Nindub is his name; to thee the plan of the House he gave." Nanshe then added some instructions of her own, reminding Gudea that the new Eninnu had to provide appropriate places for Ninurta's weapons, for his great aircraft, even for his favorite lyre.

Given these explanations and instructions Gudea returned to Lagash and secluded himself in the old temple, trying to figure out what all those instructions meant.

Most baffling to him, to begin with, was the matter of the new temple's orientation.

Stepping up to a high or elevated part of the old temple called Shugalam, "the place of the aperture, the place of determining, from which Ningirsu can see the repetition over his lands," Gudea removed some of the "spittle" (mortar? mud?) that obstructed the view, trying to fathom the secrets of the temple's construction; but he was still baffled and perplexed.

He asked for a second omen; and as he was sleeping Ningirsu/Ninurta appeared to him; "While I was sleeping, at my head he stood," Gudea wrote. The God made clear the instructions to Gudea, assuring him of constant divine help:

The God then lists for Gudea all the inner requirements of the new temple, expanding at the same time on his great powers, the awesomeness of his weapons, his memorable deeds (such as the damming of the waters) and the status he was granted by Anu, "the fifty names of lordship, by those ordained."

The construction, he tells Gudea, should begin on "the day of the new Moon," when the God will give him the proper omen- - a signal: on the evening of the New Year the God's hand shall appear holding a flame, giving off a light "that shall make the night as light as day." Ninurta/Ningirsu also assures Gudea that he will receive from the very beginning of the planning of the new Eninnu divine help: the God whose epithet was "The Bright Serpent" shall come to help build the Eninnu and its new precinct - "build it to be like the House of the Serpent, as a strong place it shall be built."

Ninurta then promises Gudea that the construction of the temple will bring the land abundance: "When my temple-terrace is completed," rains will come on time, the irrigation canals will fill up with water, even the desert "where water has not flowed" shall bloom; there will be abundant crops, and plenty of oil for cooking, and "wool in abundance shall be weighed."

Now "Gudea understood the favorable plan, a plan that was the clear message of his vision-dream; having heard the words of the lord Ningirsu, he bowed his head... Now he was greatly wise and understood great things." Losing no time Gudea proceeded to "purify the city" and organize the people of Lagash, old and young, to form work brigades and enlist themselves in the solemn task.

In verses that throw light on the human side of the story, of life and manners and social problems more than four millennia ago, we read that as a way to consecrate themselves for the unique undertaking "the whip of the overseer was prohibited, the mother did not chide her child... a maid who had done a great wrong was not struck by her mistress in the face." But the people were asked not only to become angelic; to finance the project, Gudea "levied taxes in the land; as a submission to the lord Ningirsu the taxes were increased"...

One can stop here for a moment to look ahead to another construction of a God's Residence, the one built in the wilderness of Sinai for Yahweh. The subject is recorded in detail in the Book of Exodus, beginning in chapter 25.

Then followed the most detailed architectural instructions - details which make possible the reconstructions of the Residence and its components by modern scholars. To help Moses carry out these detailed plans, Yahweh decided to provide Moses with two assistants whom Yahweh was to endow with a "divine spirit"- - "wisdom and understanding and knowledge of all manner of workmanship.''

Two men were chosen by Yahweh to be so instructed, Bezalel and Aholiab, "to carry out all of the sacred work in all of the manner that Yahweh had ordered." These instructions began with the layout plan of the Residence and make clear that it was a rectangular enclosure with its long sides (one hundred cubits) facing precisely south and north and its short sides (fifty cubits in length) facing precisely east and west, creating an east-west axis of orientation (see Fig. 44a).

By now ''greatly wise" and ''understanding great things," Gudea - to go back to Sumer some seven centuries before the Exodus - launched the execution of the divine instructions in a grand way. By canal and river he sent out boats, "holy ships on which the emblem of Nanshe was raised," to summon assistance from her followers; he sent caravans of cattle and asses to the lands of Inanna, with her emblem of the "star-disk" carried in front; he enlisted the men of Utu, "the God whom he loves."

As a result,

Cedars were brought from Lebanon, bronze was collected, shiploads of stones arrived. Copper, gold, silver, and marble were obtained. When all that was ready, it was time to make the bricks of clay. This was no small undertaking, not only because tens of thousands of bricks were needed.

The bricks - one of the Sumerian "firsts" which, in a land short of stones, enabled them to build high-rise buildings - -were not of the shape and size that we use nowadays: they were usually square, a foot or more on each side and two or three inches thick. They were not identical in all places at all times; they were sometimes just sun-dried, sometimes dried in kilns for durability; they were not always flat. but sometimes concave or convex, as their function required, to withstand structural stress.

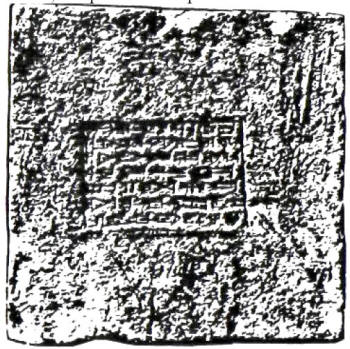

As is clear from Gudea's as well as other kings' inscriptions, when it came to temples, and even more so to ziggurats, it was the God in charge who determined the size and shape of the bricks; this was such an important step in the construction, and such an honor for the king to mold the first brick, that the kings embedded in the wet bricks a stamped inscription (Fig. 75) with a votive content. Figure 75

This custom, fortunately, made it possible for archaeologists to identify so many of the kings involved in the construction, Gudea devoted many lines in his inscriptions to the subject of the bricks. It was a ceremony attended by several Gods and was held on the grounds of the old temple. Gudea prepared himself by spending the night in the sanctuary, then bathing clean and putting on special clothes in the morning. Throughout the land it was a solemn rest day.

Gudea offered sacrifices, then went into the old Holy of Holies; there was the brick mold that the God had shown him in the vision-dream and a "holy carrying-basket." Gudea put the basket on his head. A God named Galalim led the procession. The God Ningishzidda held the brick-mold in his hand.

He let Gudea pour into the mold water from the temple's copper cup, as a good omen. On a signal from Ninurta, Gudea poured clay into the mold, all the while uttering incantations. Reverently, the inscription says, he carried out the holy rites.

The whole city of Lagash "was lying low," waiting for the outcome: will the brick come out right or will it be faulty?

Ancient, even archaic, Sumerian depictions have been found dealing with the brick ceremony; one of them (Fig. 76) shows a seated deity holding up the Holy Mold, bricks from which are carried to construct a ziggurat. The time has thus come to start building the temple; and the first step was to mark out its orientation and implant the foundation stone. Figure 76

Gudea wrote

that a new place was chosen for the new Eninnu, and archaeologists

(see map. Fig. 73) have indeed found its remains on a hill about

fifteen hundred feet away from the earlier one, on the mound marked

"A" on the excavations map.

The day was announced by the Goddess Nanshe: "Nanshe, a child of Eridu" (the city of Enki) "commanded the fulfillment of the ascertained oracle." It is our guess that it was the Day of the Equinox. At midday, "when the Sun came fully forth." the "Lord of the Observers, a Master Builder, stationed at the temple, the direction carefully planned."

As the Anunnaki were watching the procedure of determining the orientation "with much admiration," he "laid the foundation stone and marked in the earth the wall's direction." We read later on in the inscription that this Lord of the Observers, the Master Builder, was Ningishzidda; and we know from various depictions (Fig. 77) that it was a deity (recognized by his horned cap) who implanted the conical cornerstone on such occasions. Figure 77

Apart from depictions of the ceremony, showing a God with the horned headdress implanting the conical "stone," such representations cast in bronze suggest that the "stone" was actually a bronze one; the use of the term "stone" is not unusual, since all metals resulting from quarrying and mining were named with the prefix NA, meaning "stone" or "that which is mined."

In this regard it is noteworthy that in the Bible the laying of the comer or First Stone was also considered a divine or divinely inspired act signifying the Lord's blessing to the new House. In the prophecy by Zechariah about the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, he relates how Yahweh showed him in a vision "a man holding a measuring cord in his hand," and how he was told that this divine emissary would come to measure the four sides of a rebuilt and greater Jerusalem with its new Lord's House, whose stones shall rise sevenfold after the Lord will place for him the First Stone.

"And when they shall see the bronze stone in the hands of Zerubbabel" (the one chosen by Yahweh to rebuild the Temple) all nations will know that it was the Lord's will. On that occasion too the men chosen to carry out the temple's rebuilding were named by Yahweh.

In Lagash, once the cornerstone was embedded by the God Ningishzidda, Gudea was able to lay the temple's foundations, by now "like Nisaba knowing the meaning of numbers."

The ziggurat built by Gudea, scholars have concluded, was one of seven stages. Accordingly, seven blessings were pronounced as soon as the laying of the foundation stone was completed and the temple's orientation set and Gudea began to place the bricks along the marking on the ground:

Then did Gudea begin to build the "House, a dwelling he established for his lord Ningirsu ... a temple truly a Heaven-Earth mountain, its head reaching heavenward... Joyfully did Gudea erect the Eninnu with Sumer's firm bricks; the great temple he thus constructed."

With no stones to be quarried in Mesopotamia, the "Land between the rivers" which was covered with an avalanche of mud during the Deluge, the only building materials were the mud or clay bricks, and all the temples and ziggurats were so built. The statement by Gudea that the Eninnu was erected "with Sumer's firm bricks" is thus a mere statement of fact. What is puzzling is the detailed list by Gudea of other materials used in the construction.

We refer here not to the various woods and timbers, which were commonly used in temple constructions, but to the variety of metals and stones employed in the project - materials all of which had to be imported from afar. The king, we read in the inscriptions, "the Righteous Shepherd," "built the temple bright with metal" bringing copper, gold, and silver from distant lands. "He built the Eninnu with stone, he made it bright with jewels; with copper mixed with tin he held it fast."

This is undoubtedly a reference to bronze which, in addition to its use for various listed artifacts, apparently was also used to clamp together stone blocks and metals. The making of bronze, a complex process involving the mixing of copper and tin under great heat in specified proportions, was quite an art; and indeed Gudea's inscription makes it clear that for the purpose a Sangu Simug, a "priestly smith," working for the God Nintud, was brought over from the "Land of smelting."

This priestly smith, the inscription adds, "worked on the temple's facade; with two handbreadths of bright stone he faced over the brickwork; with diorite and one handbreadth of bright stone he ..." (the inscription is too damaged here to be legible). Not just the mere quantity of stones used in the Eninnu but the outright statement that the brickwork was faced with bright stone of a certain thickness - a statement that until now has not drawn the attention of scholars - is nothing short of sensational.

We know of no other instance of Sumerian records of temple construction that mention the facing or "casing" of brickwork with stones. Such inscriptions speak only of brickwork - its erection, its crumbling, its replacement - but never of a stone facing over the brick facade. Incredibly - but as we shall show, not inexplicably - the facing of the new Eninnu with bright stones, unique in Sumer, emulated the Egyptian method of facing step-pyramids with bright stone casings to give them smooth sides!

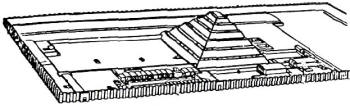

The Egyptian pyramids that were built by pharaohs began with one built by King Zoser at Sakkara (south of Memphis) circa 2650 BC. (Fig. 78). Figure 78

Rising in six steps within a rectangular sacred precinct, it was originally faced with bright limestone casing stones of which only traces now remain: its casing stones, as those of ensuing pyramids, were removed by later rulers to be used in their own monuments. The Egyptian pyramids, as we have shown and proved in The Stairway to Heaven, began with those built by the Anunnaki themselves - the Great Pyramid and its two companions at Giza.

It was they who devised the casing with bright stones of what were in their core step-pyramids, giving them their renowned smooth sides. That the new Eninnu in Lagash, commissioned by Ninurta at about the same time as Stonehenge became truly a stonehenge, emulated an Egyptian pyramid's stone facing, is a major clue for the resolution of the Stonehenge enigma. Such an unexpected link to ancient Egypt, as we have been showing, was only one among many.

Gudea himself was alluding to these connections when he stated that the shape of the Eninnu and its casing with bright stones were based on information provided by Nisaba "who was taught the plan of the temple by Enki" in the "House of Learning.'' That academy was undoubtedly in one of Enki's centers; and Egypt, it will be recalled, was the domain allotted to Enki and his descendants when Earth was divided.

The Eninnu project involved the participation of quite a number of Gods; Nisaba, who had appeared to Gudea in the first vision with the star map, was not the only female among them. Let us look at the full list, then highlight the female roles. First there was Enlil, who began the process by granting the permission to Ninurta to build the new temple. Then Ninurta appeared to Gudea, informing him of the divine decision and of his (Gudea's) selection to be the builder. In his vision Ningishzidda indicated to him the celestial point where the Sun rose, Nisaba pointed with a stylus to the favorable star, and Nindub drew the plan of the temple on a tablet.

In order to understand all that, he consulted Nanshe, the oracle Goddess. Inanna/Ishtar and Utu/Shamash enlisted their followers in obtaining the rare building materials. Ningishzidda, with the participation of a God named Galalim, was involved in molding the bricks. Nanshe chose the auspicious day on which to start the construction. Ningishzidda then determined the orientation and laid the cornerstone.

Before the Eninnu was declared fit for its purpose, Utu/Shamash

examined its alignment with the Sun. The individual shrines built

alongside the ziggurat honored Anu, Enlil, and Enki. And the final

purification and consecration rites, before Ninurta/Ningirsu and his

spouse Bau moved in, involved the deities Ninmada, Enki, Nindub, and

Nanshe.

Nanshe, who identified for Gudea the celestial role of each of the deities that appeared to him in his vision and determined the precise calendrical day (of the equinox) for orienting the temple, is called in the Gudea inscriptions "a daughter of Eridu" (Enki's city in Sumer). Indeed, in the major God Lists of Mesopotamia, she was called NIN. A - "Lady of Water" - and shown as a daughter of Ea/Enki.

The planning of waterways and the locating of fountainheads were her specialty; her celestial counterpart was the constellation Scorpio - mul GIR.TAB in Sumerian. The knowledge she contributed to the building of the Eninnu in Lagash was thus that of the Enki'ite academies. A hymn to Nanshe in her role as determiner of the New Year Day has her sitting in judgment on Mankind on that day, accompanied by Nisaba in the role of Divine Accountant who tallies and measures the sins of those who are judged, such as the sin of he "who substituted a small weight for a large weight, a small measure for a large measure."

But while the two Goddesses were frequently mentioned together, Nisaba (some scholars read her name Nidaba) was clearly listed among the Enlilites, and was sometimes identified as a half sister of Ninurta/Ningirsu. Although she was in later times deemed to be a Goddess who blesses the crops - perhaps because of her association with the calendar and weather - she was described in Sumerian literature as one who "opens men's ears," i.e. teaches them wisdom. In one of several School Essays compiled by Samuel N. Kramer (The Sumerians) from scattered fragments, the Urn mia (" Word-knower") names Nisaba as the patron Goddess of the E.DUB.BA ("House of Inscribed Tablets"), Sumer's principal academy for scribal arts.

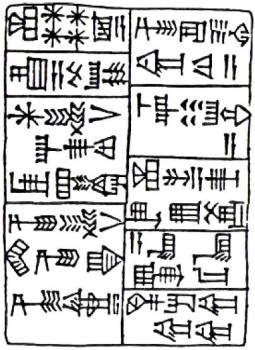

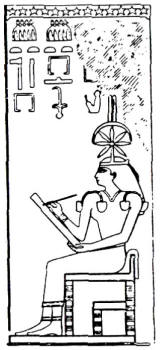

Kramer called her "the Sumerian Goddess of Wisdom." Nisaba was, in the words of D.O. Edzard (Cotter und My then im Vorderen Orient), the Sumerian Goddess of "the art of writing, mathematics, science, architecture and astronomy." Gudea specifically described her as the "Goddess who knows numbers" - a female "Einstein" of antiquity... The emblem of Nisaba was the Holy Stylus. A short hymn to Nisaba on a tablet unearthed in the ruins of the sacred precinct of Lagash (Fig. 79) describes her as "she who acquired fifty great ME's" and as possessor of the "stylus of seven numbers." Figure 79

Both numbers were associated with Enlil and

Ninurta: the numerical rank of both was fifty, and one of Enlil's

epithets (as commander of Earth, the seventh planet) was "Lord of

Seven."

The term MUL in Sumerian (Kakkab in Akkadian), meaning "celestial body," was applied to both planets and stars, and one wonders what heavenly bodies were shown on the star map possessed by Nisaba, whether they were stars or planets or (probably) both.

The opening line of the text shown in Fig. 79, paying homage to Nisaba as a great astronomer, calls her NIN MUL.MUL.LA - "Lady of Many Stars." The intriguing aspect of this formulation is that the term "many stars" is written not with a star sign together with the determinative sign for "many," but with four star signs.

The only plausible explanation for this unusual formulation is that Nisaba could point out, on her sky map, the four stars that we continue to use for determining the cardinal points. Her great wisdom and scientific knowledge were ex-pressed in Sumerian hymns by the statement that she was "perfected with the fifty great ME's" - those enigmatic "divine formulas" that, like computer disks, were small enough to be carried by hand though each contained a vast amount of information. Inanna/Ishtar, a Sumerian text related, went to Eridu and tricked Enki into giving her one hundred of them.

Nisaba, on the other hand, did not have to steal the fifty ME's. A poetic text compiled from fragments and rendered into English by William W. Hallo (in a lecture titled "The Cultic Setting of Sumerian Poetry") that he called The Blessing of Nisaba by Enki, makes clear that in addition to her Enlilite schooling Nisaba was also a graduate of the Eridu academy of Enki.

Extolling Nisaba as "Chief scribe of heaven, record-keeper of Enlil, all-knowing sage of the Gods" and exalting Enki, "the craftsman of Eridu" and his "House of Learning," the hymn says of Enki:

The "cult city" of Nisaba was called Eresh ("Foremost Abode"); its remains or location were never discovered in Mesopotamia. The fifth stanza of this poem suggests that it was located in the "Lower World" (Abzu) of Africa, where Enki oversaw the mining and metallurgical operations and conducted his experiments in genetics.

Listing the various distant locations where Nisaba was also schooled under Enki's aegis, the poem states:

A cousin of Nisaba, the Goddess

ERESH.KI.GAL ("Foremost Abode in the Great Place"), was in charge of

a scientific station in southern Africa and there shared control of

a Tablet of Wisdom with Nergal, a son of Enki, as a marriage dowry.

It is quite possible that it was there that Nisaba acquired her

additional schooling. Figure 80

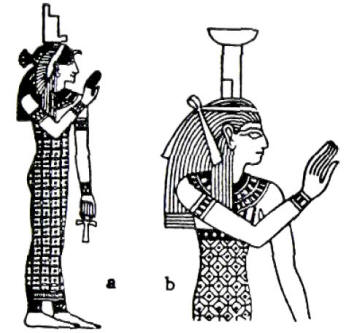

She is shown inside a gateway surmounted by the stepped viewing positions. She holds a pole-mounted viewing instrument, identified here by the crescent as one for viewing the Moon's movements, i.e. for calendrical purposes. And she is further identified by the four stars - the symbol, we believe, of Nisaba. One of the oddest statements made by Gudea when he described the deities who appeared to him concerned Nisaba: "The image of a temple-structure, a ziggurat, she carried on her head."

The headdress of Mesopotamian deities was distinguished by its pairs of horns; that Gods or Goddesses would instead wear on their heads the image of a temple or an object was absolutely unheard of. Yet, in his inscription, that is how Gudea described Nisaba. He was not imagining things. If we examine illustration 80, we will see that Nisaba is indeed carrying on her head the image of a temple-ziggurat, just as Gudea had stated.

But it is not a stepped structure; rather, it is the image of a smooth-sided pyramid - an Egyptian pyramid! Moreover, not only is the ziggurat Egyptianized - the very custom of wearing such an image on the head is Egyptian, especially as it applied to Egyptian Goddesses. Foremost of them were Isis, the sister-wife of Osiris (Fig. 81a) and Nephtys, their sister (Fig. 81b). Figures 81a and 81b

Was Nisaba, an Enlilite Goddess schooled in Enki's academy, Egyptianized enough to be wearing this kind of headgear? As we pursue this investigation, many similarities between Nisaba and Sesheta, the female assistant of Thoth in Egypt, come to light. In addition to the attributes and function of Sesheta that we have already reviewed, there were others that closely matched those of Nisaba.

They included her role as "the Goddess of the arts of writing and of science," in the words of Hermann Kees (Der Gotterglaube in Alien Aegypten). Nisaba possessed the "stylus of seven numbers"; Sesheta too was associated with the number seven. One of her epithets was "Sesheta means seven" and her name was often written hieroglyphically by the sign for seven placed above a bow. Like Nisaba, who had appeared to Gudea with the image of a temple-structure on her head, so was Sesheta depicted with the image of a twin-towered structure on her head, above her identifying star-and-bow symbol (Fig. 82). Figure 82

She was a "daughter of the sky," a chronologer and chronographer; and like Nisaba, she determined the required astronomical data for the royaltemple builders. According to the Sumerian texts, the consort of Nisaba was a God called Haia. Hardly anything is known of him, except that in the judgment procedures on New Year's Day supervised by Nanshe, he was also present, acting as the balancer of the scales.

In Egyptian beliefs Judgment Day for the pharaoh was when he died, at which time his heart was weighed to determine his fate in the Afterlife. In Egyptian theology, the God who balanced the scales was Thoth, the God of science, astronomy, the calendar, and of writing and record keeping. Such an overlapping of identities between the deities who provided the astronomical and calendrical knowledge for the Eninnu reveals an otherwise unknown state of cooperation between the Sumerian and Egyptian Divine Architects in Gudea's time.

It was, in many respects, an unusual phenomenon; it found expression in the unique shape and appearance of the Eninnu and in the establishment within its sacred precinct of an extraordinary astronomical facility. It all involved and revolved around the calendar - the gift to Mankind by the divine Keepers of the Secrets.

After the construction of the Eninnu ziggurat was completed, much effort and artistry went into its adorning, not only outside but also inside; portions, we learn, of the "inner shrine" were overlaid with "cedar panels, attractive to the eye." Outside, rare trees and bushes were planted to create a pleasant garden. A pool was built and filled with rare fish - another unusual feature in Sumerian temple precincts and one which is akin to Egyptian ones, where a sacred pool was a common feature. "The dream," Gudea wrote, "was fulfilled."

The Eninnu was completed, "like a bright mass it stands, a radiant brightness of its facing covers everything; like a mountain which glows it joyously rises." Now he turned his attention and efforts to the Girsu, the sacred precinct as such. A ravine, "a great dump" was filled up: "with the wisdom granted by Enki divinely he did the grading, enlarging the area of the temple terrace."

Cylinder A alone lists more than fifty separate shrines and temples built adjoining the ziggurat to honor the various Gods involved in the project as well as Anu, Enlil, and Enki. There were enclosures, service buildings, courts, altars, gates; residences for the various priests; and, of course, the special dwelling and sleeping quarters of Ningirsu/Ninurta and his spouse Bau. There were also special enclosures or facilities for housing the Divine Black Bird, the aircraft of Ninurta, and for his awesome weapons; as well as places at which the astronomical-calendrical functions of the new Eninnu were to be performed.

There was a special place for "the Master of Secrets," and the new Shugalam, the high place of the aperture, the "place of determining whose awesomeness is great, where the Brilliance is announced." And there were two buildings connected with the "solving of the cords" and the "binding with the cords" respectively - facilities whose purpose has eluded scholars but which had to be connected with celestial observations, for they were located next to, or were part of, the structures called ''Uppermost Chamber'' and "Chamber of the seven zones."

There were certain other features that were added to the new Eninnu and its sacred precinct that indeed made it as unique as Gudea had boasted; we shall discuss them in the detail they deserve further on. There was also a need, as the text makes clear, to await a certain specific day - New Year's Day, to be precise before Ninurta and his spouse Bau could actually move into the new Eninnu and make it their dwelling abode.

Whereas Cylinder A was devoted to the events leading to the construction of the Eninnu and the construction itself, Gudea's inscriptions on Cylinder B deal with the rites connected with the consecration of the new ziggurat and its sacred precinct and the ceremonies involved in the actual arrival of Ninurta and Bau in the Girsu - reaffirming his title as NIN.GIRSU, "Lord of Girsu" - and their entry into their new dwelling place.

The astronomical and calendrical aspects of these rites and ceremonies enhance the data with which the Cylinder A inscriptions are filled. While the arrival of the inauguration day was awaited - for the better part of a year - Gudea engaged in daily prayers, the pouring of libations, and the filling up of the new temple's granaries with food from the fields and its cattle pens with sheep from the pastures. Finally the designated day arrived:

On that day, as the "new Moon was born," the dedication ceremonies began. The Gods themselves performed the purification and consecration rites:

The third day, Gudea recorded, was a bright day. It was on that day that Ninurta stepped out - "with a bright radiance he shone." As he entered the new sacred precinct, "the Goddess Bau was advancing on his left side." Gudea "sprinkled the ground with an abundance of oil... he brought forth honey, butter, wine, milk, grain, olive oil... dates and grapes he piled up in a heap - food untouched by fire, food for the eating by the Gods."

The entertainment of the divine couple and the other Gods with fruits and other uncooked foods went on until midday.

It was also the day on which the harvest began:

Following a decree of Ninurta and the Goddess Nanshe, there followed seven days of repentance and atonement in the land.

At the end of the seven days, on the tenth day of the month, Gudea entered the new temple and for the first time performed there the rites of the High Priest, "lighting the fire in the temple-terrace before the bright heavens." A depiction on a cylinder seal from the second millennium BC., found at Ashur, may well have preserved for us the scene that had taken place a thousand years earlier in Lagash: it shows a High Priest (who as often as not was also the king, as in the case of Gudea) lighting a fire on an altar as he faces the God's ziggurat, while the "favorite planet" is seen in the heavens (Fig. 83).

Figure 83

And the God Ninurta, promising Lagash and its people abundance, that "the land may bear whatever is good," to Gudea himself said:

Appropriately, the Cylinder B inscription concludes thus:

|