|

They would take the brunt of the engine's noise and smoke that, somehow, always managed to seep through unseen cracks. A dining car was placed between the sections as a subtle barrier between the two classes of travelers. By today's Standards, the environment was drab. Chairs and mattresses were hard. Surfaces were metal or scarred wood. Colors were dark green and gray.

The shades were drawn, but through the open door, one could see mahogany paneling, velvet drapes, plush armchairs, and a well stocked bar.

Porters with white serving coats were busying themselves with routine chores. And there was the distinct aroma of expensive cigars. Other cars in the station bore numbers on each end to distinguish them from their dull brothers. But numbers were not needed for this beauty. On the center of each side was a small plaque bearing but a single word: ALDRICH.

As an investment associate of J.P. Morgan, he had extensive holdings in banking, manufacturing, and public utilities. His son-in-law was John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Sixty years later, his grandson, Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, would become Vice-President of the United States.

Had they forgotten something? Was there a problem with the engine?

CONCENTRATION OF WEALTH

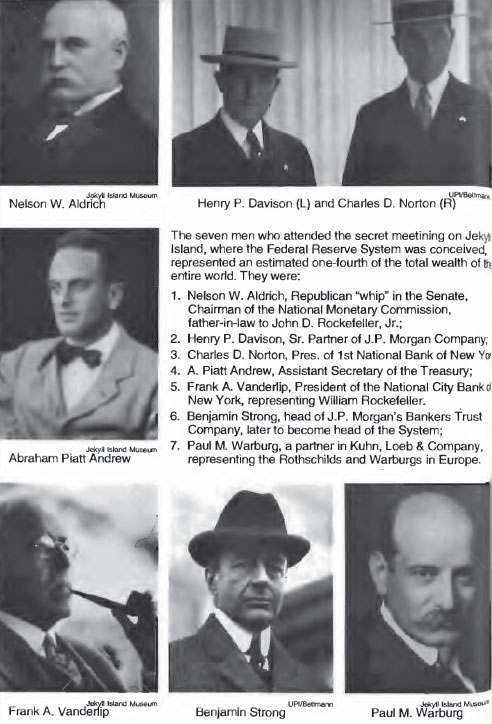

In the United States, there were two main focal points of this control: the Morgan group and the Rockefeller group. Within each orbit was a maze of commercial banks, acceptance banks, and investment firms. In Europe, the same process had proceeded even further and had coalesced into the Rothschild group and the Warburg group.

An article appeared in the New York Times on May 3, 1931, commenting on the death of George Baker, one of Morgan's closest associates.

It said:

The reference was only to those in the Morgan group, (members of the Jekyll Island Club), It did not include the Rockefeller group or the European financiers. When all of these are combined, the previous estimate that one-fourth of the world's wealth was represented by these groups is probably conservative.

In spite of his efforts, however, the final report of the committee at large was devastating:

Under our system of issuing and distributing corporate securities the investing public does not buy directly from the corporation.

The securities travel from the issuing house through middlemen to the investor. It is only the great banks or bankers with access to the mainsprings of the concentrated resources made up of other people's money, in the banks, trust companies, and life insurance companies, and with control of the machinery for creating markets and distributing securities, who have had the power to underwrite or guarantee the sale of large-scale security issues.

The men who through their control over the funds of our railroad and industrial companies are able to direct where such funds shall be kept, and thus to create these great reservoirs of the people's money are the ones who are in a position to tap those reservoirs for the ventures in which they are interested and to prevent their being tapped for purposes which they do not approve...

Quickly, the crew threw a switch, and the engine nudged the last car onto a siding where, just as quickly, it was uncoupled and left behind. When passengers stepped onto the platform at the terminal a few moments later, their train appeared exactly as it had been when they boarded.

They could not know that their travelling companions for the night, at that very instant, were joining still another train which, within the hour, would depart Southbound once again.

But, by that time, the Sea Islands that sheltered the coast from South Carolina to Florida already had become popular as winter resorts for the very wealthy. One such island, just off the coast of Brunswick, had recently been purchased by J.P. Morgan and several of his business associates, and it was here that they came in the fall and winter to hunt ducks or deer and to escape the rigors of cold weather in the North. It was called Jekyll Island.

Who were Mr. Aldrich's guests? Why were they here? Was there anything special happening?

Mr. Davison, who was one of the owners of Jekyll Island and who was well known to the local paper, told them that these were merely personal friends and that they had come for the simple amusement of duck hunting. Satisfied that there was no real news in the event, the reporters returned to their office.

It is difficult to imagine any event in history - including preparation for war - that was shielded from public view with greater mystery and secrecy.

In more specific terms, the purpose and, indeed, the actual outcome of this meeting was to create the blueprint for the Federal Reserve System.

Even now, the accepted view is that the meeting was relatively unimportant, and only paranoid unsophisticates would try to make anything out of it.

Ron Chernow writes:

Little by little, however, the story has been pieced together in amazing detail, and it has come directly or indirectly from those who actually were there.

Furthermore, if what they say about their own purposes and actions does not constitute a classic conspiracy, then there is little meaning to that word.

At any rate, the opening paragraph contained a dramatic but highly accurate summary of both the nature and purpose of the meeting:

I am not romancing. I am giving to the world, for the first time, the real story of how the famous Aldrich currency report, the foundation of our new currency system, was written.2

1 - Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990), p. 129. 2 - "Men Who Are Making America/' by B.C. Forbes, Leslie's Weekly, October 19, 1916, p. 423.

In 1930, Paul Warburg wrote a massive book - 1750 pages in all - entitled The Federal Reserve System, Its Origin and Growth. In this tome, he described the meeting and its purpose but did not mention eitheNts location or the names of those who attended.

But he did say:

Then, in a footnote he added:

An interesting insight to Paul Warburg's attendance at the Jekyll Island meeting came thirty-four years later, in a book written by his son, James.

James had been appointed by F.D.R. as Director of the Budget and, during World War II, as head of the Office of War Information. In his book he described how his father, who didn't know one end of a gun from the other, borrowed a shotgun from a friend and carried it with him to the train to disguise himself as a duck hunter.2

Stephenson continues with a description of the encounter at Brunswick station.

He tells us that, shortly after they arrived, the station master walked into the private car and shocked them by his apparent knowledge of the identities of everyone on board. To make matters even worse, he said that a group of reporters were waiting outside.

Davison took charge.

No one claims to know what story was told standing on the railroad ties that morning, but a few moments later Davison returned with a broad smile on his face.

Stephenson continues:

1. Paul Warburg, The Federal Reserve

System: Its Origin and Growth (New York: Macmillan, 1930), Vol. I, p. 58. It

is apparent that Warburg wrote this line two years before the book was

published.

In the February 9, 1935, issue of the Saturday Evening Post, an article appeared written by Frank Vanderlip.

In it he said:

THE STRUCTURE WAS PURE CARTEL

A cartel is a group of independent businesses

which join together to coordinate the production, pricing, or marketing of

their members. The purpose of a cartel is to reduce competition and thereby

increase profitability. This is accomplished through a shared monopoly over

their industry which forces the public to pay higher prices for their goods

or services than would be otherwise required under free-enterprise

competition.

They were often competitors, and there is little doubt that there was considerable distrust between them and skillful maneuvering for favored position in any agreement. But they were driven together by one overriding desire to fight their common enemy.

The enemy was competition.

Almost all banks in the 1880s were national banks, which means they were chartered by the federal government. Generally, they were located in the big cities, and were allowed by law to issue their own currency in the form of bank notes.

Even as early as 1896, however, the number of non-national banks had grown to sixty-one per cent, and they already held fifty-four per cent of the country's total banking deposits. By 1913, when the Federal Reserve Act was passed, those numbers were seventy-one per cent non-national banks holding fifty-seven per cent of the deposits.1

In the eyes of those duck hunters from New York, this was a trend that simply had to be reversed.

Rates were low enough to attract serious borrowers who were confident of the success of their business ventures and of their ability to repay, but they were high enough to discourage loans for frivolous ventures or those for which there were alternative sources of funding - for example, one's own capital. That balance between debt and thrift was the result of a limited money supply.

Banks could create loans in excess of their actual deposits, as we shall see, but there was a limit to that process. And that limit was ultimately determined by the supply of gold they held. Consequently, between 1900 and 1910, seventy per cent of the funding for American corporate growth was generated internally, making industry increasingly independent of the banks.1

Even the federal government was becoming thrifty. It had a growing stockpile of gold, was systematically redeeming the Greenbacks - which had been issued during the Civil War - and was rapidly reducing the national debt.

To accomplish this, the money supply simply had to be disconnected from gold and made more plentiful or, as they described it, more elastic.

This is because, when banks accept a customer's deposit, they give in return a "balance" in his account. This is the equivalent of a promise to pay back the deposit anytime he wants. Likewise, when another customer borrows money from the bank, he also is given an account balance which usually is withdrawn immediately to satisfy the purpose of the loan.

This creates a ticking time bomb because, at that point, the bank has issued more promises to "pay-on-demand" than it has money in the vault. Even though the depositing customer thinks he can get his money any time he wants, in reality it has been given to the borrowing customer and no longer is available at the bank.

And, because only about three per cent of these accounts are actually retained in the vault in the form of cash - the rest having been put into even more loans and investments - the bank's promises exceed its ability to keep those promises by a factor of over three hundred-to-one.2

1. William Greider, Secrets ofthe

Temple (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987), p. 274, 275. Also Kolko, p. 145

As long as only a small percentage

Bankruptcy usually follows in due course.

Instead of withdrawing their funds at the teller's window, they simply wrote checks to purchase goods or services. People receiving those checks took them to a bank for deposit. If that bank happened to be the same one from which the check was drawn, then all was well, because it was not necessary to remove any real money from the vault.

But if the holder of the check took it to another bank, it was quickly passed back to the issuing bank and settlement was demanded between banks.

While the Downtown Bank is demanding payment from the Uptown Bank, the Uptown Bank is also clearing checks and demanding payment from the Downtown bank. As long as the money flow in both directions is equal, then everything can be handled with simple bookkeeping. But if the flow is not equal, then one of the banks will have to actually send money to the other to make up the difference.

If the amount of money required exceeds a few percentage points of the bank's total deposits, the result is the same as a run on the bank by depositors. This demand of money by other banks rather than by depositors is called a currency drain.

It was dangerous enough to loan ninety per cent of their customers' savings (keeping only one dollar in reserve out of every ten), but that had proven to be adequate most of the time. Some banks, however, were tempted to walk even closer to the precipice.

They pushed the ratio to ninety-too per cent, ninety-five per cent, ninety-nine per cent. After all, the way a bank makes money is to collect interest, and the only way to do that is to make loans. The more loans, the better. And, so, there was a practice among some of the more reckless banks to "loan up," as they call it.

Which was another way of saying to push dawn their reserve ratios.

No major currency drains would ever occur.

The entire banking industry might collapse under such a system, but not individual banks - at least not those that were part of the cartel. All would walk the same distance from the edge, regardless of how close it was. Under such uniformity, no individual bank could be blamed for failure to meet its obligations. The blame could be shifted, instead, to the "economy" or "government policy" or "interest rates" or "trade deficits" or the "exchange-value of the dollar" or even to the "capitalist system" itself.

Thus, the bank which pursued a more reckless

lending policy had to draw against its reserves in order to make payments to

the more conservative banks and, when those funds were exhausted, it usually

was forced into bankruptcy. Historian John Klein tells us that,

In other words, the "panics" and resulting bank failures were caused, not by negative factors in the economy, but by currency drains on the banks which were loaned up to the point where they had practically no reserves at all.

The banks did not fail because the system was weak. The system failed because the banks were weak.

To do this, they had to find a way to force all banks to walk the same distance from the edge, and, when the inevitable disasters happened, to shift public blame away from themselves. By making it appear to be a problem of the national economy rather than of private banking practice, the door then could be opened for the use of tax money rather than their own funds for paying off the losses.

The most important task before them, therefore, can be stated as objective number five:

The task was a delicate one.

The American people did not like the concept of

a cartel. The idea of business enterprises joining together to fix prices

and prevent competition was alien to the free-enterprise system. It could

never be sold to the voters. But, if the word cartel was not used, if the

venture could be described

Henceforth, the cartel would operate as a central bank. And even that was to be but a generic expression. For purposes of public relations and legislation, they would devise a name that would avoid the word bank altogether and which would conjure the image of the federal government itself.

Furthermore, to create the impression that there would be no concentration of power, they would establish regional branches of the cartel and make that a main selling point.

Stephenson tells us:

But political expediency required that such plans be concealed from the public.

As John Kenneth Galbraith explained it:

1. Stephenson, p. 378.

Because of this knowledge, Paul Warburg became the dominant and guiding mind throughout all of the discussions. Even a casual perusal of the literature on the creation of the Federal Reserve System is sufficient to find that he was, indeed, the cartel's mastermind.

Galbraith says,

Professor Edwin Seligman, a member of the international banking family of J. & W. Seligman, and head of the Department of Economics at Columbia University, writes that,

He had come to the United States only nine years previously. Soon after arrival, however, and with funding provided mostly by the Rothschild group, he and his brother, Felix, had been able to buy partnerships in the New York investment banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Company, while continuing as partners in Warburg of Hamburg.1

1. Anthony Sutton, Wall Street and FDR (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House, 1975), p. 92.

Within twenty years, Paul would become one of the wealthiest men in America with an unchallenged domination over the country's railroad system.

This was, of course, a central bank, and it was one of the cartel models used in the construction of the Federal Reserve System. The Reichsbank, incidentally, a few years later would create the massive hyperinflation that occurred in Germany, wiping out the middle class and the entire German economy as well.

These attracted wide attention in both financial and academic circles and set the intellectual climate for all future discussions regarding banking legislation. In these treatises, Warburg complained that the American monetary system was crippled by its dependency on gold and government bonds, both of which were in limited supply.

What America needed, he argued, was an elastic money supply that could be expanded and contracted to accommodate the fluctuating needs of commerce. The solution, he said, was to follow the German example whereby banks could create currency solely on the basis of "commercial paper," which is banker language for I.O.U.s from corporations.

In March of that year, for example, The Nezv York Times published an eleven-part series written by Warburg explaining and expounding what he called the Reserve Bank of the United States.1

To cover the fact that a central bank is merely a cartel which has been legalized, its proponents had to lay down a thick smoke screen of technical jargon focusing always on how it would supposedly benefit commerce, the public, and the nation; how it would lower interest rates, provide funding for needed industrial projects, and prevent panics in the economy.

There was not the slightest glimmer that, underneath it all, was a master plan which was designed from top to bottom to serve private interests at the expense of the public.

He said:

Precisely. A union of banks.

He said:

And that is about as good a definition of a cartel as one is likely to find.

In an article published in July of that year in a magazine called The Independent, he boasted:

One of the most widely-used textbooks on this subject says:

Even the most naive student must sense a grave contradiction between this cherished view and the System's actual performance.

Since its inception, it has presided over the crashes of 1921 and 1929; the Great Depression of '29 to '39; recessions in '53, '57, '69, '75, and '81; a stock market "Black Monday" in '87; and a 1000% inflation which has destroyed 90% of the dollar's purchasing power.3

1. Quoted by KoLko, Triumph, p. 235.

That incredible loss in value was quietly transferred to the federal government in the form of hidden taxation, and the Federal Reserve System was the mechanism by which it was accomplished.

The consequences of wealth confiscation by the Federal-Reserve mechanism are now upon us.

In the current decade,

FIRST REASON TO ABOLISH THE SYSTEM

There can be no argument that the System has failed in its stated objectives. Furthermore, after all this time, after repeated changes in personnel, after operating under both political parties, after numerous experiments in monetary philosophy, after almost a hundred revisions to its charter, and after the development of countless new formulas and techniques, there has been more than ample opportunity to work out mere procedural flaws.

It is not unreasonable to conclude, therefore, that the System has failed, not because it needs a new set of rules or more intelligent directors, but because it is incapable of achieving its stated objectives.

The painful answer is: those were never its true objectives.

When one realizes the circumstances under which it was created, when one contemplates the identities of those who authored it, and when one studies its actual performance over the years, it becomes obvious that the System is merely a cartel with a government facade. There is no doubt that those who run it are motivated to maintain full employment, high productivity, low inflation, and a generally sound economy.

They are not interested in killing the goose that lays such beautiful golden eggs. But, when there is a conflict between the public interest and the private needs of the cartel - a conflict that arises almost daily - the public will be sacrificed. That is the nature of the beast. It is foolish to expect a cartel to act in any other way.

For example, William Greider was a former Assistant Managing Editor for The Washington Post. His book, Secrets of The Temple, was published in 1987 by Simon and Schuster. It was critical of the Federal Reserve because of its failures, but, according to Greider, these were not caused by any defect in the System itself, but merely because the economic factors are "sooo complicated" that the good men who have struggled to make the System work have just not yet been able to figure it all out.

But, don't worry, folks, they're working on it! That is exactly the kind of powder-puff criticism which is acceptable in our mainstream media. Yet, Greider's own research points to an entirely different interpretation.

Speaking of the System's origin, he says:

Anthony Sutton, former Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution for War, Revolution and Peace, and also Professor of Economics at California State University, Los Angeles, provides a somewhat deeper analysis.

1. Greider, p. 275.

He writes:

The real significance of the journey to Jekyll Island and the creature that was hatched there was inadvertently summarized by the words of Paul Warburg's admiring biographer, Harold Kellock:

1. Sutton, Wall Street and F.D.R., p,

94.

Those who attended represented the great financial institutions of Wall Street and, indirectly, Europe as well. The reason for secrecy was simple. Had it been known that rival factions of the banking community had joined together, the public would have been alerted to the possibility that the bankers were plotting an agreement in restraint of trade - which, of course, is exactly what they were doing.

What emerged was a cartel agreement with five objectives: stop the growing competition from the nation's newer banks; obtain a franchise to create money out of nothing for the purpose of lending; get control of the reserves of all banks so that the more reckless -ones would not be exposed to currency drains and bank runs; get the taxpayer to pick up the cartel's inevitable losses; and convince Congress that the purpose was to protect the public.

It was realized that the bankers would have to become partners with the politicians and that the structure of the cartel would have to be a central bank. The record shows that the Fed has failed to achieve its stated Objectives. That is because those were never its true goals.

As a banking cartel, and in terms of the five

objectives stated above, it has been an Unqualified success.

Chapter

Two

That, of course, is one of the more controversial assertions made in this book.

Yet, there is little room for any other interpretation when one confronts the massive evidence of history since the System was created. Let us, therefore, take another leap through time. Having jumped to the year 1910 to begin this story, let us now return to the present era.

We would stare with incredulity at men dressed like aliens from another planet; throwing their bodies against each other; tossing a funny shaped object hack and forth; fighting over it as though it were of great value, yet, occasionally kicking it out of the area as though it were worthless and despised; chasing each other, knocking each other to the ground and then walking away to regroup for another surge; all this with tens of thousand of spectators riotously shouting in unison for no apparent reason at all.

Without a basic understanding that this was a game and without knowledge of the rules of that game, the event would appear as total chaos and universal madness.

Which, as far as monetary matters is concerned, is the common state of the vast majority of Americans today.

The procedure by which this is accomplished is as follows:

The banks derive profit from this easy money, not by spending it, but by lending it to others and collecting interest.

The only way to do this and balance the books once again is to draw upon the capital which was invested by the bank's stockholders or to deduct the loss from the bank's current profits. In either case, the owners of the bank lose an amount equal to the value of the defaulted loan.

So, to them, the loss becomes very real. If the bank is forced to write off a large amount of bad loans, the amount could exceed the entire value of the owners' equity. When that happens, the game is over, and the bank is insolvent.

But the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Federal Deposit Loan Corporation now guarantee that massive loans made to large corporations and to other governments will not be allowed to fall entirely upon the bank's owners should those loans go into default.

This is done under the argument that, if these corporations or banks are allowed to fail, the nation would suffer from vast unemployment and economic disruption.

More on that in a moment.

The larger the loan, the better it is, because it will produce the greatest amount of profit with the least amount of effort A single loan to a third-world country netting hundreds of millions of dollars in annual interest is just as easy to process - if not easier - than a loan for $50,000 to a local merchant on the shopping mall. If the interest is paid, it's gravy time.

If the loan defaults, the federal government will "protect the public" and, through various mechanisms described shortly, will make sure that the banks continue to receive their interest.

There are no such guarantees for the small loans. The public will not swallow the line that bailing out the little guy is necessary to save the system. The dollar amounts are too small. Only when the figures become mind-boggling does the ploy become plausible.

They make a profit from interest on the loan, not repayment of the loan. If a loan is paid off, the bank merely has to find another borrower, and that can be an expensive nuisance. It is much better to have the existing borrower pay only the interest and never make payments on the loan itself. That process is called rolling over the debt. One of the reasons banks prefer to lend to governments is that they do not expect those loans ever to be repaid.

When Walter Wriston was chairman of the Citicorp Bank in 1982, he extolled the virtue of the action this way:

When this activity is carried out in the United States, as it is weekly, it is described as a Treasury bill auction.

But when basically the same process is conducted abroad in a foreign language, our news media usually speak of a country's "rolling over its debts." The perception remains that some form of disaster is inevitable. It is not.

Certainly in an era of $100-billion deficits, no one lending money to our Government by buying a Treasury bill expects that it will be paid at maturity in any way except by our Government's selling a new bill of like amount.1

1. "Banking Against Disaster/' by Walter B. Wriston, The New York Times, September 14, 1982.

Furthermore, it is predictable that most unsound loans eventually will go into default. When the borrower finally declares that he cannot pay, the bank responds by rolling over the loan.

This often is stage managed to appear as a concession on the part of the bank but, in reality, it is a significant forward move toward the objective of perpetual interest.

So the bank's next move is to create additional money out of nothing and lend that to the borrower so he will have enough to continue paying the interest, which by now must be paid on the original loan plus the additional loan as well. What looked like certain disaster suddenly is converted by a brilliant play into a major score.

This not only maintains the old loan on the books as an asset, it actually increases the apparent size of that asset and also results in higher interest payments, thus, greater profit to the bank.

He is not interested in making interest payments

with nothing left for himself. He comes to realize that he is merely working

for the bank and, once again, interest payments stop. The opposing teams go

into a huddle to plan the next move, then rush to the scrimmage

Finally, a "compromise" is worked out.

As before, the bank agrees to create still more money out of nothing and lend that to the borrower to cover the interest on both of the previous loans but, this time, they up the ante to provide still additional money for the borrower to spend on something other than interest. That is a perfect score. The borrower suddenly has a fresh supply of money for his purposes plus enough to keep making those bothersome interest payments.

The bank, on the other hand, now has still larger assets, higher interest income, and greater profits.

What an exciting game!

This realization usually comes when the interest payments become so large they represent almost as much as the entire corporate earnings or the country's total tax base. This time around, roll-overs with larger loans are rejected, and default seems inevitable.

A voice over the public address system announces:

Rescheduling usually means a combination of a lower interest rate and a longer period for repayment.

The effect is primarily cosmetic. It reduces the monthly payment but extends the period further into the future. This makes the current burden to the borrower a little easier to carry, but it also makes repayment of the capital even more unlikely.

It postpones the day of reckoning but, in the meantime, you guessed it: The loan remains as an asset, and the interest payments continue.

The borrower realizes he can never repay the capital and flatly refuses to pay interest on it. It is time for the Final Maneuver.

1- "Overseas Lending... Trigger for A Severe Depression?" The Banking Safety Digest (U.S. Business Publishing/Veribanc, Wakefield, Massachusetts), August, 1989, p. 3.

The banks can absorb the losses of their bad loans to multinational corporations and foreign governments, but that is not according to the rules.

It would be a major loss to the stockholders who would receive little or no dividends during the adjustment period, and any chief executive officer who embarked upon such a course would soon be looking for a new job. That this is not part of I the game plan is evident by the fact that, while a small portion of the Latin American debt has been absorbed, the banks are continuing to make gigantic loans to governments in other parts of the world, particularly Africa, Red China, and Eastern European nations.

For reasons which will be analyzed in chapter four, there is little hope that the performance of these loans will be different than those in Latin America.

But the most important reason for not absorbing the losses is that there is a standard play that can still [breathe life back into those dead loans and reactivate the bountiful income stream that flows from them.

The captains of both teams approach the Referee and the Game Commissioner to request that the game be extended. The reason given is that this is in the interest of the public, the spectators who are having such a wonderful time and [who will be sad to see the game ended.

They request also that, while the spectators are in the stadium enjoying themselves, the barking-lot attendants be ordered to quietly remove the hub caps from every car.

These can be sold to provide money for additional salaries for all the players, including the referee and, of course, the Commissioner himself. That is only fair since they are now working overtime for the benefit of the spectators. When the deal is finally struck, the horn will blow three times, and a roar of joyous relief will sweep across the stadium.

Not only will there be unemployment and hardship at home, there will be massive disruptions in world markets. And, since we are now so dependent on those markets, our exports will drop, foreign capital will dry up, and we will suffer greatly.

What is needed, they will say, is for Congress to provide money to the borrower, either directly or indirectly, to allow him to continue to pay interest on the loan and to initiate new spending programs which will be so profitable he will soon be able to pay everyone back.

After all, the amount to be lost through the write-off was created out of nothing in the first place and, without this Final Maneuver, the entirety would be written off.

Furthermore, this modest write down is dwarfed by the amount to be gained through restoration of the income stream.

That means to guarantee future payments should the borrower again default. Once Congress agrees to this, the government becomes a co-signer to the loan, and the inevitable losses are finally lifted from the ledger of the bank and placed onto the backs of the American taxpayer.

All of these mechanisms extract payments from the American people and channel them to the deadbeat borrowers who then send them to the banks to service their loans. Very little of this money actually comes from taxes.

Almost all of it is generated by the Federal Reserve System. When this newly created money returns to the banks, it quickly moves out again into the economy where it mingles with and dilutes the value of the money already there. The result is the appearance of rising prices but which, in reality, is a lowering of the value of the dollar.

They do not realize that these groups also are victimized by a monetary system which is constantly being eroded in value by and through the Federal Reserve System.

A man from the audience rose and asked angrily:

And the audience of several hundred people actually cheered in enthusiastic approval!

Yet, many of them still manage to bungle themselves into insolvency. As we shall see in a later section of this study, insolvency actually is inherent in the system itself, a system called fractional-reserve banking.

Lo and behold, there isn't enough to go around and, when that happens, the cat is finally out of the bag. The bank must close its doors, and the depositors still waiting in line outside are... well, just that: still waiting.

In other words, they should keep cash in the vault equal to 100% of their depositors' accounts. When we give our hat to the hat-check girl and obtain a receipt for it, we don't expect her to rent it out while we eat dinner hoping she'll get it back - or one just like it - in time for our departure.

We expect all the hats to remain there all the time so there will be no question of getting ours back precisely when we want it.

They are told they can have their money any time they want it and they are paid interest as well. Even if they do not receive interest, the bank does, and this is how so many customer services can be offered at little or no direct cost. Occasionally, a thirty-day or sixty-day delay will be mentioned as a possibility, but that is greatly inadequate for deposits which have been transformed into ten, twenty, or thirty-year loans. The banks are simply playing the odds that everything will work out most of the time.

Students of finance are told that there simply is no other way for the system to function. Once that premise is accepted, then all attention can be focused, not on the inherent fraud, but on ways and means to live with it and make it as painless as possible.

That is banker language meaning it stands ready to create money out of nothing and immediately lend it to any bank in trouble. (Details on how that is accomplished are in chapter eight.)

But there are practical limits to just how far that process can work. Even the Fed will not support a bank that has gotten itself so deeply in the hole it has no realistic chance of digging out. When a bank's bookkeeping assets finally become less than its liabilities, the rules of the game call for transferring the losses to the depositors themselves. This means they pay twice: once as taxpayers and again as depositors.

The mechanism by which this is accomplished is called the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

THE FDIC PLAY

The money to do this comes out of a special fund which is derived from assessments against participating banks. The banks, of course, do not pay this assessment. As with all other expenses, the bulk of the cost ultimately is passed on to their customers in the form of higher service fees and lower interest rates on deposits.

When moral hazard is present, it is normal for people to become careless, and the likelihood increases that what is being insured against will actually happen. An example would be a government program forcing everyone to pay an equal amount into a fund to protect them from the expense of parking fines.

One hesitates even to mention this absurd proposition lest some enterprising politician should decide to put it on the ballot.

Therefore, let us hasten to point out that, if such a numb-skull plan were adopted, two things would happen:

The FDIC operates exactly in this fashion.

Depositors are told their insured accounts are protected in the event their bank should become insolvent. To pay for this protection, each bank is assessed a specified percentage of its total deposits. That percentage is the same for all banks regardless of their previous record or how risky their loans. Under such conditions, it does not pay to be cautious.

The banks making reckless loans earn a higher rate of interest than those making conservative loans.

They also are far more likely to collect from the fund, yet they pay not one cent more. Conservative banks are penalized and gradually become motivated to make more risky loans to keep up with their competitors and to get their "fair share" of the fund's protection. Moral hazard, therefore, is built right into the system.

As with protection against parking tickets, the FDIC increases the likelihood that what is being insured against will actually happen.

It is not a solution to the problem, it is part of the problem.

Banks with solid loans on their books would be able to obtain protection for their depositors at reasonable rates, because the chances of the insurance company having to pay would be small. Banks with unsound loans, however, would have to pay much higher rates or possibly would not be able to obtain coverage at any price.

Depositors, therefore, would know instantly, without need to investigate further, that a bank without insurance is not a place where they want to put their money. In order to attract deposits, banks would have to have insurance. In order to have insurance at rates they could afford, they would have to demonstrate to the insurance company that their financial affairs are in good order.

Consequently, banks which failed to meet the minimum standards of sound business practice would soon have no customers and would be forced out of business. A voluntary, private insurance program would act as a powerful regulator of the entire banking industry far more effectively and honestly than any political scheme ever could.

Unfortunately, such is not the banking world of today.

As we have already seen, the first line of defense in this scheme is to have large, defaulted loans restored to life by a Congressional pledge of tax dollars. If that should fail and the bank can no longer conceal its insolvency through creative bookkeeping, it is almost certain that anxious depositors will soon line up to withdraw their money - which the bank does not have.

The second line of defense, therefore, is to have the FDIC step in and make those payments for them.

If the bank is rescued in this fashion, management is fired and what is left of the business usually is absorbed by another bank. Furthermore, the value of the stock will plummet, but this will affect the small stockholders only. Those with controlling interest and those in management know long in advance of the pending catastrophe and are able to sell the bulk of their shares while the price is still high.

The people who create the problem seldom suffer the economic consequences of their actions.

If that amount were in existence, it could be held by the banks themselves, and an insurance fund would not even be necessary. Instead, the FDIC operates on the same assumption as the banks: that only a small percentage will ever need money at the same time. So the amount held in reserve is never more than a few percentage points of the total liability.

Typically, the FDIC holds about $1.20 for every $100 of covered deposits. At the time of this writing, however, that figure had slipped to only 70 cents and was still dropping. That means that the financial exposure is about 99.3% larger than the safety net which is supposed to catch it.

The failure of just one or two large banks in the system could completely wipe out the entire fund.

In the final stage of this process, therefore, the FDIC itself runs out of money and turns, first to the Treasury, then to Congress for help. This step, of course, is an act of final desperation, but it is usually presented in the media as though it were a sign of the system's great strength.

U.S. News & World Report blandly describes it this way:

1. "How Safe Are Deposits in Ailing Banks, S&L's?" U.S. News & World Report, March 25, 1985, p. 73.

Isn't that wonderful? It sort of makes one feel rosy all over to know that the fund is so well secured.

The public picks up a portion of these I.O.U.s, and the Federal Reserve buys the rest. If there is a monetary crisis at hand and the size of the loan is great, the Fed will pick up the entire issue.

The old paycheck doesn't buy as much any more,

so we learn to get along with a little bit less. But, see? The bank's doors

are open again, and all the depositors are happy - until they return to

their cars and discover the missing hub caps! That is what is meant by "the full faith and credit of the federal government."

The central fact to understanding these events is that all the money in the banking system has been created out of nothing through the process of making loans.

A defaulted loan, therefore, costs the bank little of tangible value, but it shows up on the ledger as a reduction in assets without a corresponding reduction in liabilities. If the bad loans exceed the size of the assets, the bank becomes technically insolvent and must close its doors. The first rule of survival, therefore, is to avoid writing off large, bad loans and, if possible, to at least continue receiving interest payments on them.

To accomplish that, the endangered loans are rolled over and increased in size.

This provides the borrower with money to continue paying interest plus fresh funds for new spending. The basic problem is not solved, but it is postponed for a little while and made worse.

The FDIC is not insurance, because the presence of "moral hazard" makes the thing it supposedly protects against more likely to happen.

A portion of the FDIC funds are derived from assessments against the banks. Ultimately, however, they are paid by the depositors themselves. When these funds run out, the balance is provided by the Federal Reserve System in the form of freshly created new money.

This floods through the economy causing the appearance of rising prices but which, in reality, is the lowering of the value of the dollar. The final cost of the bailout, therefore, is passed to the public in the form of a hidden tax called inflation.

In the previous chapter, we offered the whimsical analogy of a sporting event to clarify the maneuvers of monetary and political scientists to bail out those commercial banks which comprise the Federal-Reserve cartel.

The danger in such an approach is that it could leave the impression the topic is frivolous. So, let us abandon the analogy and turn to reality. Now that we have studied the hypothetical rules of the game, it is time to check the scorecard of the actual play itself, and it will become obvious that this is no trivial matter.

A good place to start is with the rescue of a consortium of banks which were holding the endangered loans of Penn Central Railroad.

In 1970, it also became the nation's biggest bankruptcy. It was deeply in debt to just about every bank that was willing to lend it money, and that list included Chase Manhattan, Morgan Guaranty, Manufacturers Hanover, First National City, Chemical Bank, and Continental Illinois. Officers of the largest of those banks had been appointed to Penn Central's board of directors as a condition for obtaining funds, and they gradually had acquired control over the railroad's Management.

The banks also held large blocks of Penn Central stock in their trust departments.

Chris Welles, in The Last Days of the Club, describes what happened:

More to the point of this study is the fact that virtually all of the major management decisions which led to Penn Central's demise were made by or with the concurrence of its board of directors, which is to say, by the banks that provided the loans.

In other words, the bankers were not in trouble because of Penn Central's poor management, they were Penn Central's poor management. An investigation conducted in 1972 by Congressman Wright Patman, Chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee, revealed the following: The banks provided large loans for disastrous expansion and diversification projects.

They loaned additional millions to the railroad so it could pay dividends to its stockholders. This created the false appearance of prosperity and artificially inflated the market price of its stock long enough to dump it on the unsuspecting public.

Thus, the banker-managers were able to engineer a three-way bonanza for themselves.

They,

1. Chris Welles, The Last Days ofthe

Club (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1975), pp. 398-99.

Reports from the Securities and Exchange Commission showed that the company's top executives had disposed of their stock in this fashion at a personal savings of more than $1 million.1

That is a common practice among corporate raiders who use borrowed funds to seize control of a company, bleed off its assets to other enterprises which they also control, and then toss the debt-ridden, dying carcass upon the remaining stockholders or, in this case, the taxpayers.

The banking cartel, commonly called the Federal Reserve System, was created for exactly this kind of bailout. Arthur Burns, who was the Fed's chairman, would have preferred to provide a direct infusion of newly created money, but that was contrary to the rules at that time.

In his own words:

1- "Penn Central: Bankruptcy Filed

After Loan Bill Fails/' 1970 Congressional Quarterly Almanac (Washington,

D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, 1970), p. 811.

The company's cash crisis came to a head over a weekend and, in order to avoid having the corporation forced to file for bankruptcy on Monday morning.

Burns called the homes of the heads of the Federal Reserve banks around the country and told them to get the word out immediately that the System was anxious to help.

On Sunday, William Treiber, who was the first vice-president of the New York branch of the Fed, contacted the chief executives of the ten largest banks in New York and told them that the Fed's Discount Window would be wide open the next morning. Translated, that means the Federal Reserve System was prepared to create money out of nothing and then immediately loan it to the commercial banks so they, in turn, could multiply and re-lend it to Perm Central and other corporations, such as Chrysler, which were in similar straits.1

Furthermore, the rates at which the Fed would make these funds available would be low enough to compensate for the risk, speaking of what transpired on the following Monday, Burns boasted:

Looking back at the event, Chris Welles approvingly describes it as,

Finest hour or not, the banks were not that interested in the proposition unless they could be assured the taxpayer would co-sign the loans and guarantee payment.

So the action inevitably shifted back to Congress. Perm Central's executives, bankers, and union representatives came in droves to explain how the railroad's continued existence was in the best interest of the public, of the working man, of the economic system itself. The Navy Department spoke of protecting the nation's "defense resources." Congress, of course, could not callously ignore these pressing needs of the nation.

It responded by ordering a retroactive, 13½ per cent pay raise for all union employees. After having added that burden to the railroad's cash drain and putting it even deeper into the hole, it then passed the Emergency Rail Services Act of 1970 authorizing $125 million in federal loan guarantees.3

AMTRAK took over the passenger services of Perm Central, CONRAIL assumed operation of its freight services, along with five other Eastern railroads. CONRAIL technically is a private corporation. When it was created, however, 85% of its stock was held by the government.

The remainder was held by employees. Fortunately, the government's stock was sold in a public offering in 1987. AMTRAK continues under political control and operates at a loss. It is sustained by government subsidies - which is to say by taxpayers. In 1997, Congress dutifully gave it another $5.7 billion and, by 1998, liabilities exceeded assets by an estimated $14 billion.

CONRAIL, on the other hand, since it was returned to the private sector, has experienced an impressive turnaround and has been running at a profit - paying taxes instead of consuming them.

LOCKHEED

The Bank of America and several smaller banks had loaned $400 million to the Goliath and they were not anxious to lose the bountiful interest-income stream that flowed from that; nor did they wish to see such a large bookkeeping asset disappear from their ledgers. In due course, the banks joined forces with Lockheed's management, stockholders, and labor unions, and the group descended on Washington.

Sympathetic politicians were told that, if Lockheed were allowed to fail, 31,000 jobs would be lost, hundreds of sub contractors would go down, thousands of suppliers would be forced into bankruptcy, and national security would be seriously jeopardized.

What the company needed was to borrow more money and lots of it. But, because of its current financial predicament, no one was willing to lend. The answer? In the interest of protecting the economy and defending the nation, the government simply had to provide either the money or the credit.

The government agreed to guarantee payment on an additional $250 million in loans - an amount which would put Lockheed 60% deeper into the debt hole than it had been before. But that made no difference now. Once the taxpayer had been made a co-signer to the account, the banks had no qualms about advancing the funds.

Other defense contractors which had operated more efficiently would lose business, but that could not be proven. Furthermore, a slight increase in defenses expenditures would hardly be noticed.

Under such an arrangement, it makes little difference if the loans were paid back or not.

Taxpayers were doomed to pay the bill either way.

In 1975, New York had reached the end of its credit rope and was unable even to make payroll. The cause was not mysterious. New York had long been a welfare state within itself, and success in city politics was traditionally achieved by lavish promises of benefits and subsidies for "the poor."

Not surprisingly, the city also was notorious for political corruption and bureaucratic fraud. Whereas the average large city employed thirty-one people per one-thousand residents, New York had forty nine. That's an excess of fifty-eight per cent. The salaries of these employees far outstripped those in private industry. While an X-ray technician in a private hospital earned $187 per week, a porter working for the city earned $203.

The average bank teller earned $154 per week, but a change maker on the city subway received $212. And municipal fringe benefits were fully twice as generous as those in private industry within the state. On top of this mountainous overhead were heaped additional costs for free college educations, subsidized housing, free medical care, and endless varieties of welfare programs.

Even after transfer payments from Albany and Washington added state and federal taxes to the take, the outflow continued to exceed the inflow. There were now only three options: increase city taxes, reduce expenses, or go into debt. The choice was never in serious doubt. By 1975, New York had floated so many bonds it had saturated the market and could find no more lenders.

Two billion dollars of this debt was held by a small group of banks, dominated by Chase Manhattan and Citicorp.

Starvation, disease, and crime would run rampant through the city.

It would be a disgrace to America. David Rockefeller at Chase Manhattan persuaded his friend Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor of West Germany, to make a statement to the media that the disastrous situation in New York could trigger an international financial crisis.

All of this money, of course, would first have to be borrowed by Congress which was, itself, deeply in debt. And most of it would be created, directly or indirectly, by the Federal Reserve System. That money would be taken from the taxpayer through the loss of purchasing power called inflation, but at least the banks could be repaid, which is the object of the game.

New York City has continued to be a welfare utopia, and it is unlikely that it will ever get out of debt.

It had rolled over its debt to the banks many times, and the game was nearing an end. In spite of an OPEC oil embargo which had pushed up the cost of gasoline and in spite of the increasing popularity of small-automobile imports, the company had continued to build the traditional gas hog. It was now saddled with a mammoth inventory of unsaleable cars and with a staggering debt which it had acquired to build those cars.

America was also experiencing high interest rates which, coupled with fears of U.S. military involvement in Cambodia, had led to a slump in the stock market. Banks felt the credit crunch keenly and, in one of those rare instances in modern history, the money makers themselves were scouring for money.

The banks agreed to write down $600 million of their old loans and to exchange an additional $700 million for preferred stock.

Both of these moves were advertised as evidence the banks were taking a terrible loss but were willing to yield in order to save the nation. It should be noted, however, that the value of the stock which was exchanged for previously uncollectable debt rose drastically after the settlement was announced to the public.

Furthermore, not only did interest payments resume on the balance of the old loans, but the banks now replaced the written down portion with fresh loans, and these were far superior in quality because they were fully guaranteed by the taxpayers. So valuable was this guarantee that Chrysler, in spite of its previously poor debt performance, was able to obtain loans at 10.35% interest while its more solvent competitor, Ford, had to pay 13.5%.

Applying the difference of 3.15% to one and-a-half billion dollars, with a declining balance continuing for only six years, produces a savings in excess of $165 million. That is a modest estimate of the size of the federal subsidy.

The real value was far greater because, without it, the corporation would have ceased to exist, and the banks would have taken a loss of almost their entire loan exposure.

Banking services are uninterrupted and, aside from a change in name, most customers are unaware of the transaction. This option is generally selected for small and medium banks. In both a payoff and a sell off, the FDIC takes over the bad loans of the failed bank and supplies the money to pay back the insured depositors.

Irvine Sprague, a former director of the FDIC, explains:

1- Irvine H. Sprague, Bailout: An Insider's Account ofBank Failures and Rescues (New York: Basic Books, 1986), p, 23.

That's right, he said everyone - insured or not - is fully protected.

The banks which comprise the elect few generally are the large ones. It is only when the number of dollars at risk becomes mind numbing that a bailout can be camouflaged as protection of the public.

Sprague says:

1. Sprague, p. 68.

Favoritism toward the large banks is obvious at many levels.

One of them is the fact that, in a bailout, the FDIC covers all deposits, whether insured or not. That is significant, because the banks pay an assessment based only on their insured deposits. So, if un insured deposits are covered also, that coverage is free - more precisely, paid by someone else.

What deposits are uninsured?

Those in excess of $100,000 and those held outside the United States. Which banks hold the vast majority of such deposits? The large ones, of course, particularly those with extensive overseas operations.2 The bottom line is that the large banks get a whopping free ride when they are bailed out. Their uninsured accounts are paid by FDIC, and the cost of that benefit is passed to the smaller banks and to the taxpayer.

This is not an oversight. Part of the plan at Jekyll Island was to give a competitive edge to the large banks.

In 1971, Unity Bank and Trust Company in the Roxbury section of Boston found itself hopelessly insolvent, and the federal agency moved in. This is what was found: Unity's capital was depleted; most of its loans were bad; its loan collection practices were weak; and its personnel represented the worst of two worlds: overstaffing and inexperience.

The examiners reported that there were two persons for every job, and neither one had been taught the job.

As Sprague, himself, admitted:

But Unity Bank was different.

It was located in a black neighborhood and was minority owned. As is often the case when government agencies are given discretionary powers, decisions are determined more by political pressures than by logic or merit, and Unity was a perfect example. In 1971, the specter of rioting in black communities still haunted the halls of Congress.

Would the FDIC allow this bank to fail and assume the awesome responsibility for new riots and bloodshed?

Sprague answers:

1- Sprague, pp. 41-42.

On July 22, 1971, the FDIC declared that the continued operation of Unity Bank was, indeed, essential and authorized a direct infusion of $1.5 million.

Although appearing on the agency's ledger as a loan, no one really expected repayment. In 1976, in spite of the FDIC's own staff report that the bank's operations continued "as slipshod and haphazard as ever/' the agency rolled over the "loan" for another five years. Operations did not improve and, on June 30, 1982, the Massachusetts Banking Commissioner finally revoked Unity's charter.

There were no riots in the streets, and the FDIC quietly wrote off the sum of $4,463,000 as the final cost of the bailout.

From that point forward, however, the FDIC game plan was strictly according to Hoyle. The next bailout occurred in 1972 involving the $1.5 billion Bank of the Common-Wealth of Detroit.

Commonwealth had funded most of its phenomenal growth through loans from another bank, Chase Manhattan in New York.

When Commonwealth went belly up, largely due to securities speculation and self dealing on the part of its management, Chase seized 39% of its common stock and actually took control of the bank in an attempt to find a way to get its money back.

FDIC director Sprague describes the inevitable sequel:

1. Sprague, p. 68.

The bankers argued that Commonwealth must not be allowed to fold because it provided "essential" banking services to the community.

That was justified on two counts:

It was unclear what the minority issue had to do with it inasmuch as every neighborhood in which Commonwealth had a branch was served by other banks as well.

Furthermore, if Commonwealth were to be liquidated, many of those branches undoubtedly would have been purchased by competitors, and service to the communities would have continued. Judging by the absence of attention given to this issue during discussions, it is apparent that it was merely thrown in for good measure, and no one took it very seriously.

In any event, the FDIC did not want to be accused of being indifferent to the needs of Detroit's minorities and it certainly did not want to be a destroyer of free-enterprise competition. So, on January 17,1972, Commonwealth was bailed out with a $60 million loan plus numerous federal guarantees.

Chase absorbed some losses, primarily as a result of Commonwealth's weak bond portfolio, but those were minor compared to what would have been lost without FDIC intervention.

Better to have financial power concentrated in Saudi Arabia than in Detroit. The bank continued to flounder and, in 1983, what was left of it was resold to the former Detroit Bank & Trust Company, now called Comerica.

Thus the dreaded concentration of local power was realized after all, but not until Chase Manhattan was able to walk away from the deal with most of its losses covered.

First Perm was the nation's twenty-third largest bank with assets in excess of $9 billion. It was six times the size of Commonwealth; nine hundred times larger than Unity. It was also the nation's oldest bank, dating back to the Bank of North America which was created by the Continental Congress in 1781.

As long as the economy expanded, these gambles were profitable, and the stockholders loved him dearly. When his gamble in the bond market turned sour, however, the bank plunged into a negative cash flow.

By 1979, First Penn was forced to sell off

several of its profitable subsidiaries in order to obtain operating funds,

and it was carrying $328 million in questionable loans. That was $16 million

more than the entire stockholder investment. The bank was insolvent, and the

time had arrived to hit up the taxpayer for the loss.

They were joined by spokesmen from the nation's top three: Bank of America, Citibank, and of course the ever-present Chase Manhattan.

They argued that, not only was the bailout of First Penn essential" for the continuation of banking services in Philadelphia, it was also critical to the preservation of world economic stability.

The bank was so large, they said, if it were allowed to fall, it would act as the first domino leading to an international financial crisis. At first, the directors of the FDIC resisted that theory and earned the angry impatience of the Federal Reserve.

Sprague recalls:

The Fed's role as lender of last resort first generated contention between the Fed and FDIC during this period.

The Fed was lending heavily to First Pennsylvania, fully secured, and Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said he planned to continue funding indefinitely until we could work out a merger or a bailout to save the bank.

1. Sprague, pp. 88-89.

So, in due course, a bailout package was put together which featured a $325 million loan from FDIC, interest free for the first year and at a subsidized rate thereafter; about half the market rate.

Several other banks which were financially tied to First Perm, and which would have suffered great losses if it had folded, loaned an additional $175 million and offered a $1 billion line of credit FDIC insisted on this move to demonstrate that the banking industry itself was helping and that it had faith in the venture. To bolster that faith, the Federal Reserve opened its Discount Window offering low-interest funds for that purpose.

The bank has remained on shaky ground, however, and the final page of this episode has not yet been written.

With assets of $42 billion and with 12,000 employees working in offices in almost every major country in the world, its loan portfolio had undergone spectacular growth. Its net income on loans had literally doubled in just five years and by 1981 had rocketed to an annual figure of $254 million. It had become the darling of the market analysts and even had been named by Dun's Review as one of the five best managed companies in the country.

These opinion leaders failed to perceive that the spectacular performance was due, not to an expertise in banking or investment, but to the financing of shaky business enterprises and foreign governments which could not obtain loans anywhere else. But the public didn't know that and wanted in on the action. For awhile, the bank's common stock actually sold at a premium over others which were more prudently managed.

The Mexican and Argentine debt crisis was coming to a head, and a series of major corporate bankruptcies were receiving almost daily headlines. Continental had placed large chunks of its easy money with all of them. When these events caused the bank's credit raring to drop, cautious depositors began to withdraw their funds, and new funding dwindled to a trickle.

The bank became desperate for cash to meet its daily expenses. In an effort to attract new money, it began to offer unrealistically high rates of interest on its CDs. Loan officers were sent to scour the European and Japanese markets and to conduct a public relations campaign aimed at convincing market managers that the bank was calm and steady.

David Taylor, the bank's chairman at that time, said:

1- Quoted by Chernow, p. 657.

In the fantasy land of modern finance, glitter is often more important than substance, image more valuable than reality.

The bank paid the usual quarterly dividend in

August, in spite of the fact that this intensified its cash crunch. As with

the Perm Central Railroad twelve years earlier, that move was calculated to

project an image of business-as-usual prosperity. And the ploy worked - for a while, at least. By November, the public's confidence had been restored, and the bank's stock recovered to its pre-Penn Square level. By March of 1983, it had risen even higher. But the worst was yet to come.

On Tuesday, May 8, Reuters, the British news agency, moved a story on its wire service stating that banks in the Netherlands, West Germany, Switzerland, and Japan had increased their interest rate on loans to Continental and that some of them had begun to withdraw their funds. The story also quoted the bank's official statement that rumors of pending bankruptcy were "totally preposterous."

Within hours, another wire, the Commodity News Service, reported a second rumor: that a Japanese bank was interested in buying Continental.

A billion dollars in Asian money moved out that first day. The next day - a little more than twenty-four hours following Continental's assurance that bankruptcy was totally preposterous, its long-standing customer, the Board of Trade Clearing Corporation, located just down the street - withdrew $50 million. Word of the defection spread through the financial wire services, and the panic was on. It became the world's first global electronic bank run.

Chernow says:

Sprague writes:

This was the golden moment for which the Federal Reserve and the FDIC were created.

Without government intervention, Continental would have collapsed, its stockholders would have been wiped out, depositors would have been badly damaged, and the financial world would have learned that banks, not only have to talk about prudent management, they actually have to adopt it. Future banking practices would have been severely altered, and the long-term economic benefit to the nation would have been enormous.

But with government intervention, the discipline of a free market is suspended, and the cost of failure or fraud is politically passed to the taxpayers.

Depositors continue to live in a dream world of false security, and banks can operate recklessly and fraudulently with the knowledge that their political partners in government will come to their rescue when they get into trouble.

Which means that the bank paid insurance premiums into the fund based on only four per cent of its total coverage, and the taxpayers now would pick up the other ninety-six per cent.

FDIC director Sprague explains:

That course was never seriously considered by any of the players.

From the beginning, there were only two questions: how to come to Continental's rescue by covering its total liabilities and, equally important, how to politically justify such a fleecing of the taxpayer. As pointed out in the previous chapter, the rules of the game require that the scam must always be described as a heroic effort to protect the public.

In the case of Continental, the sheer size of the numbers made the ploy relatively easy.

There were so many depositors involved, so many billions at risk, so many other banks interlocked, it could be claimed that the economic fabric of the entire nation - of the world itself - was at stake. And who could say that it was not so.

Sprague argues the case in familiar terms:

1. Sprague, p. 184.

There would be some preliminary lip service given to the necessity of allowing the banks themselves to work out their own problem. That would be followed by a plan to have the banks and the government share the burden. And that finally would collapse into a mere public-relations illusion.

In the end, almost the entire cost of the bailout would be assumed by the government and passed on to the taxpayer.

At the May 15 meeting, Treasury Secretary Regan spoke eloquently about the value of a free market and the necessity of having the banks mount their own rescue plan, at least for a part of the money.

To work out that plan, a summit meeting was arranged the next morning among the chairmen of the seven largest banks:

The meeting was perfunctory at best.

The bankers knew full well that the Reagan Administration would not risk the political embarrassment of a major bank failure. That would make the President and the Congress look bad at re-election time. But, still, some kind of tokenism was called for to preserve the Administration's conservative image. So, with urging from the Fed and the Treasury, the consortium agreed to put up the sum of $500 million - an average of only $71 million for each, far short of the actual need.

Chernow describes the plan as "make-believe" and says "they pretended to mount a rescue."1

Sprague supplies the details:

1- Chernow, p. 659.

The final bailout package was a whopper.

Basically, the government took over Continental Illinois and assumed all of its losses. Specifically, the FDIC took $4.5 billion in bad loans and paid Continental $35 billion for them. The difference was then made up by the infusion of $1 billion in fresh capital in the form of stock purchase. The bank, therefore, now had the federal government as a stockholder controlling 80 per cent of its shares, and its bad loans had been dumped onto the taxpayer.

In effect, even though Continental retained the appearance of a private institution, it had been nationalized.

If the bank had been allowed to fail, and the FDIC had been required to cover the losses, the drain would have emptied the entire fund with nothing left to cover the liabilities of thousands of other banks. In other words, this one failure alone, if it were allowed to happen, would have wiped out the entire FDIC!

That's one reason the bank had to be kept operating, losses or no losses, and that's why the Fed had to be involved in the bail out In fact, that was precisely the reason the System was created at Jekyll Island:

The scam could never work unless the Fed was able to create money out of nothing and pump it into the banks along with "credit" and "liquidity" guarantees.

Which means, if the loans go sour, the money is eventually extracted from the American people through the hidden tax called inflation. That's the meaning of the phrase "lender of last resort."

While explaining this fleecing of the taxpayer to the Senate Banking Committee, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said:

With those words, he has confirmed one of the more controversial assertions of this book.

There could be no better example of this than the bail out of Continental Illinois. In 1983, the bank paid a premium into the fund of only $6.5 million to protect its insured deposits of $3 billion. The actual liability, however - including its institutional and overseas deposits - was ten times that figure, and the FDIC guaranteed payment on the whole amount.

As Sprague admitted,

How true.

Within the same week that the FDIC and the Fed were providing billions in payments, stock purchases, loans, and guarantees for Continental Illinois, it closed down the tiny Bledsoe County Bank of Pikeville, Tennessee, and the Planters Trust and Savings Bank of Opelousas, Louisiana. During the first half of that year, forty-three smaller banks failed without an FDIC bailout.

In most cases, a merger was arranged with a larger bank, and only the uninsured deposits were at risk. The impact of this inequity upon the banking system is enormous. It sends a message to bankers and depositors alike that small banks, if they get into trouble, will be allowed to fold, whereas large banks are safe regardless of how poorly or fraudulently they are managed.

As a New York investment analyst stated to news reporters, Continental Illinois, even though it had just failed, was,

1- Quoted by Greider, p. 628.

Nothing could be better calculated to drive the small independent banks out of business or to force them to sell out to the giants.

And that, in fact, is exactly what has been happening. Since 1984, while hundreds of small banks have been forced out of business, the average size of the banks which remain - with government protection - has more than doubled. It will be recalled that this advantage of the big banks over their smaller competitors was also one of the objectives of the Jekyll Island plan.

Their lament was that it should now protect them in the same paternalistic fashion. Voters and politicians were silent on the issue, apparently awed by the sheer size of the numbers and the specter of economic chaos. Decades of public education had left their mark. After all, wasn't this exactly what government schools have taught is the proper function of government? Wasn't this the American way?

Even Ronald Reagan, viewed as the national champion of economic conservatism, praised the action.

From aboard Air Force One on the way to California, the President said:

The Reagan endorsement brought into focus one of the most amazing phenomena of the 20th century:

William Greider, a former writer for the liberal Washington Post and The Rolling Stone, complains:

In the past, conservative scholars and pundits had objected loudly at any federal intervention in the private economy, particularly emergency assistance for failing companies.

Now, they hardly seemed to notice. Perhaps they would have been more vocal if the deed had been done by someone other than the conservative champion, Ronald Reagan.2

The FDIC pumped $130 million into its main banking unit and took warrants for 55% ownership. The pattern had been set. By accepting stock in a failing bank in return for bailing it out, the government had devised an ingenious way to nationalize banks without calling it that. Issuing stock sounds like a business transaction in the private sector.

And the public didn't seem to notice the reality that Uncle Sam was going into banking.

Here are some of the big games of the season and

their final scores.

Directors concealed reality from the stockholders and made additional loans so the company could pay dividends to keep up the false front. During this time, the directors and their banks unloaded their stock at unrealistically high prices. When the truth became public, the stockholders were left holding the empty bag.

The bailout, which was engineered by the Federal Reserve, involved government subsidies to other banks to grant additional loans.

Then Congress was told that the collapse of Perm Central would be devastating to the public interest. Congress responded by granting $125 million in loan guarantees so that banks would not be at risk. The railroad eventually failed anyway, but the bank loans were covered. Perm Central was nationalized into AMTRAK and continues to operate at a loss.

This was accomplished by granting lucrative defense contracts at non-competitive bids. The banks were paid back.

News of the deal pushed up the market value of that stock and largely offset the loan write-off. The banks' previously uncollectable debt was converted into a government-backed, interest-bearing asset.

So the FDIC pumped in a $60 million loan plus federal guarantees of repayment. Commonwealth was sold to an Arab consortium. Chase took a minor write down but converted most of its potential loss into government-backed assets.

So the FDIC gave a $325 million loan - interest-free for the first year, and at half the market rate thereafter. The Federal Reserve offered money to other banks at a subsidized rate for the specific purpose of relending to First Perm. With that enticement, they advanced $175 million in immediate loans plus a $1 billion line of credit.