|

16. TACTICS, STRATEGIES,

FORGERIES, ILLUSIONS

From a western point of view, religion

and politics have been neatly and cleanly separated from one another since

the modern era (18th century). In this sense a clear distinction

is drawn here between the spread of Tantric Buddhism and the question of Tibet’s international legal status. However,

for an ancient culture like the Tibetan one, such a division is just not

possible. In it, all levels — the mystic, the mythic, the symbolic, and the

ritual — are addressed by every political event. From a Tibetan viewpoint

it is thus completely logical that the liberation of the Land of Snows from the claws of the Chinese dragon

be blown up into an exemplary deed that should benefit the whole planet.

“To save Tibet means to save the world!” is a

widespread slogan, even among committed Westerners.

Just like the teachings of the Buddha,

the political issue of Tibet at first evoked little resonance among

the western public. Those who broached the topic of the fate of the Tibetan

people in American and European governmental circles generally encountered

rejection and disinterest. But this dismissive stance changed in the

mid-eighties. With increasing frequency, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai

Lama was officially received by western heads of state who had previously

refused to be in public contact with him for fear of Chinese protests.

The “Tibet Lobby”

Since 1985 the so-called Tibet

lobby has been at work

in numerous countries. This is a cross-party collection of parliamentary

representatives who in their respective parliaments advocate a Tibet resolution that morally condemns China for its constant human rights abuses

and “cultural genocide”. A recognition of Tibet as an autonomous state is not linked

to such resolutions. At the Tibet

Support Groups Conference in Bonn (in 1996), Tim Nunn from England gave a paper on the methods (the upaya) of successful lobbying:

well-groomed appearance, diplomatic language, proper dress, skilled

presentation, and the like. Mr. Nunn was able to point to successes — 131

members of the British Lower House had engaged themselves for the cause of

the Land of Snows in London (Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung, 1996, pp.

77ff.).

In the USA the lawyer Michael van Walt van Praag

has successfully argued the interests of the Tibetan government in exile to

both Senators and Congressmen. He succeeded in getting a resolution on Tibet passed in the U.S. Senate. One of his

greatest political successes was when in 1991 the Kundun was permitted to take his place in the rotunda and

address the American House of Congress. Afterwards he met with President

George Bush. Bush signed an official document in which Tibet was described as am “occupied

country”. Since 1990 The Voice of

America has begun broadcasting programs in Tibetan. A new broadcaster, Free Asia, which also has a Tibet department, has recently been approved

by Congress. As of 1997, the State

Department appointed a “special representative for Tibet” who is supposed to have the task of

negotiating between the Kundun

and China.

In early September 1995, the Dalai Lama

smilingly embraced Senator Jesse Helms, renowned for his ultra-conservative

stance. This was a high point in the thoroughgoing reverence the

Republicans have shown him.

The Democrats barely acknowledged such

conservative solidarity, since it was they who smoothed the way for the

“liberal” god-king to reach a broad public. The American President, Bill

Clinton, and his Vice-president, Al Gore, were initially reserved and

ambivalent towards the Dalai Lama, whom they have met several times. The

American government’s position is expressed unambiguously in a statement

from 1994: „Because we do not recognize Tibet as an independent state, the

United States does not conduct diplomatic relations with the self-styled

the ‘Tibetan government-in-exile’“ it says there (Goldstein, 1997, p. 121).

But after several meetings with

President Clinton and his wife Hillary the god-king was able to make a

lasting impression on the presidential couple. Clinton committed himself as never before to

resolving the question of Tibet. One of the major points of his trip

to China (in 1998) was to encourage Jiang Zemin to take up

contact with the Dalai Lama. Every western head of state who visits the

Middle Kingdom now reiterates this, which has led to success: in the

meantime the two parties (Beijing and Dharamsala) confer constantly

behind closed doors.

In 1989 the Fourteenth Dalai Lama was

awarded the Nobel peace prize. The fact that he received this high accolade

has less to do with the political situation in Tibet than, above all, the bloody events in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, where numerous Chinese students

protesting against the regime lost their lives. The West wanted to morally

condemn China and the Tibet lobby was successful in proposing an

honoring of His Holiness as the best means of doing so.

From now on the god-king possessed an

international prominence like never before. The Oslo award could almost be said to have

granted him a passport and access to the majority of world heads of state.

There was hardly a president who still in the face of Chinese protests

refused to officially receive the god-king, at least as a religious

representative. In Ireland, France, Liechtenstein, Austria, Lithuania,

Latvia, Bulgaria, Russia, the USA, Canada, England, Switzerland, Germany,

Sweden, Israel, Japan, Taiwan, Gabun, Australia, New Zealand, several South

American countries — everywhere the “modest monk” was honored like a

pontiff.

In 1996 the lobbyists succeeded in

maneuvering Germany into a spectacular confrontation with China through the passing of a resolution Tibet in the Bundestag (the German lower house). The resolution was

supported by all parties in parliament, be they green, left, liberal, or

conservative. The paradoxical side to this move was that both the Dalai

Lama and the Chinese were able to profit from it whilst the naïve Germans

had to pay up. This coup represents the Kundun’s

party’s greatest political success in the West to date. On the other hand,

the Chinese succeeded in inducing the intimidated German federal government

into continuing to grant China the much desired Hermes securities

formerly refused them. For Beijing, with this agreement in hand, the

question of Tibet in its relations with Germany was resolved for now. Even if we

cannot speak of a direct cooperation here, according to the cui bonum principle the two Asian

parties profited greatly by drawing an essentially uninvolved nation into

the conflict.

The media management of the Kundun’s followers is by now

perfect. Numerous offices in all countries, above all the Tibet Information Network (TIN) in London, supply the press with material about

the serious shortcomings in the Land of Snows, life in the community of Tibetan

exiles, and the activities of the god-king. There is successful cooperation

with Chinese dissidents. Reports from Beijing, which admittedly can only be treated

with great caution but nonetheless include much important information, are

uniformly dismissed by Dharamsala as communist propaganda. This

one-sidedness in the assessment of Tibetan affairs has in the meantime also

been adopted by the western press corps.

For example, when at the invitation of

the Chinese the German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, visited Lhasa as the first

western head of government and afterwards announced that the situation in

the Tibet capital was by no means so criminal as it was portrayed to be by

the Dalai Lama’s office, he was lambasted in the media, who declared that

he was prepared to sell his morals for financial considerations. But when

he was there, the former American President Jimmy Carter, renowned for his

great commitment to human rights, also gained the same impression

(Grunfeld, 1996, p. 232).

The issue of Tibet has become an important means of

anchoring Tantric Buddhism in the West. As a political issue it appears in the West to be completely

divorced from any religious instrumentalization. The Kundun appears in public as a campaigner for peace, a democrat,

a humanist, as an advocate of the oppressed. This skillfully adapted

western/ethical “mixture” gains him unrestricted access to the highest

levels of government. Although some politicians may see a confirmation of

their ideals in the (ostensible) behavior of the Dalai Lama, fundamentally

it is probably power-political motives which determine Western policy on Asia. The West’s relationship with China is namely extremely ambivalent. On the

one hand there is a hope for good economic and political ties to the

prospering country with its unbounded markets, on the other a deep-seated

fear of a future Chinese superpower. The political situation in Tibet and the circumstances of the Tibetans

in exile afford sufficient grounds to be employed as an argument against a

potential Chinese imperialism.

The “Greens”

In Germany the issue of Tibet was first taken up by green politicians, primarily by the

parliamentary representatives Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian. Their

pro-Tibetan intervention is still marked by a continuing success. “Major

entertainers and environmentalists”, wrote the Spiegel magazine, “have found a common denominator in their

commitment to the kingdom on the roof of the world. Hollywood meets Robin

Hood — Tibet’s Buddhism is the common denominator”

(Spiegel, 16/1998, p. 109). Petra

Kelly’s selfless engagement was later interpreted as a form of “engaged Buddhism”

whose principle concerns were said to include the defense of human rights,

ecological responsibility, and sexual equality. [1]

The Kundun cleverly co-opted all

these western demands and suddenly (at the end of the eighties) appeared on

the political stage as a spearhead of the global ecological movement.

„Green

politics” and environmental issues have in the meantime attained a central

place within the political propaganda of the Tibetans in exile. There are

hundreds of conferences such as the one introduced by His Holiness in 1993

under the title of „Ecological responsibility: A dialog with Buddhism”. The

Kundun is a member of the

ecologically oriented Goal Forum of

Spiritual and Parliamentary Leaders on Human Survival. In 1992 he

visited the Greenpeace flagship,

the Rainbow Warrior. And at the

„global forum” in Rio de Janeiro the Dalai Lama

had far-reaching things to say about the earth’s problems: „This blue

planet of ours is a delightful habitat. Its life is our life; its future

our future. Indeed, the earth acts like a mother to all. Like children, we

are dependent on them. ... Our Mother Earth is teaching us a lesson in

universal responsibility”, the god-king announced emotionally. (www.tibet.com/Eco/dleco4.html)

Since the late eighties it has become

normal at international environmental meetings all around the world to

describe the Tibet of old as an ecological paradise, where wild gazelles

and “snow lions” eat from the monks’ hands, as the Dalai Lama’s brother

(Thubten Jigme Norbu) put it at a Tibet conference in Bonn (in 1996). For

thousands of years, it says in edifying writings, the Tibetans have revered

plants and animals as their equals. “Historical” idylls such as the

following are taken literally by innocently trusting Westerners:

„The Tibetan

traditional heritage, which is known to be over three thousand years

old[!], can be distinguished as one of [the] foremost traditions of the

world in which … humankind and its natural environment have persistently

remained in perfect harmony” (Huber, 2001, p. 360).

What glowed in the past should also

shine in the future. Accordingly many western followers of the Kundun imagine how the once

flourishing garden will bloom again after his return to the Land of Snows. His Holiness is also generously

accommodating towards this image of desire and promises to found the first

ecological state on earth in a “liberated” Tibet — for many “Greens” a

glimmer of hope in a world that constantly neglects its environmental

responsibilities.

Today, among many committed members of

the international “ecological scene”, being green, environmentally

friendly, nature-loving, vegetarian, and Tibetan Buddhist, are all but

identical. But is there any truth in such an equivalence? Was the Tibet of old really an “earthly garden of

paradise”? Is the essence of Tantric Buddhism pro-nature and animal-loving?

Tibetan Buddhism’s

hostility towards nature

No complicated research is required to

establish that the inhabitants of the Tibet of old, like all highlands

peoples, had an ambivalent relationship with nature, in which fear and

horror in the face of constant catastrophes (turns in the weather, cold,

famines, accidents, illnesses) predominated. Nature, which was (and often

still is) in fact experienced animistically

as being inhabited by spirits, was only rarely a friend and partner;

instead, most of the time it was a malevolent and destructive force, in

many instances a terrifying demoness. We have presented some of these

anti-human nature spirits in our chapter on Anarchy and Buddhism. Using violence, trickery, and magic they

have to be compelled, tamed, and not unrarely killed.

In a comprehensive study (Civilized Shamans), the Tibet

researcher Geoffrey Samuel has demonstrated that the violent subjugation of

a wild nature is a drama constantly repeated within the Tibetan monastic

civilization: beginning with the nailing down of the Tibetan primeval earth

mother, Srinmo, by King Songtsen Gampo so as to erect the

central shrines of the Land of Snows over her wounds, the construction of

every Lamaist temple (no matter where in the world) was and is prefaced by

a ritual that refreshes the dreadful stigmatization of the “earth mother”. Srinmo is undoubtedly the (Tibetan)

emanation of “Mother Earth” or “Mother Nature” whom the Dalai Lama so

emotionally pleads to rescue at international ecology congresses ("the

earth acts like a mother to all”). It was the Kundun himself — if we take his doctrine of incarnation

literally — who in the form of Songtsen

Gampo many centuries ago nailed down “Mother Earth” (Srinmo). He himself laid the bloody

foundations (the maltreated body of Srinmo)

upon which his clerical and andocentric system rests. It is he himself who

repeats this aggressive “taming act” at every public performance of the Kalachakra ritual: before a sand

mandala is created, the local nature spirits (some interpreters say the

earth mother Srinmo) are nailed

to the ground with phurbas

(ritual daggers).

The equation of nature with the

feminine principle is an archetypical move that we find in most cultures.

The Greek Gaia and Tibetan Srinmo are just two different names

for the same divine substance of the earth mother. In European alchemy,

nature is the starting point (the prima

materia) for the magic experiments and likewise a principium feminile. We have examined the close interconnection

of alchemy and Tantrism in detail and proved that in both systems the

feminine principle is sacrificed for the benefit of a masculine

experimenter. By adopting for ourselves the tantric way of seeing things in

which everything is linked to everything else, we were able to recognize

the nailing down of Srinmo (the

symbol-laden primal event of Tibetan history) as the historical predecessor

of the “tantric/alchemic female sacrifice”. Songtsen Gampo sacrificed the “earth mother” so as to acquire

her energies for himself, just as every tantra master sacrifices his karma mudra so as to absorb her gynergy.

In recent decades numerous books have

appeared that address the disrespect, enslavement, and dismemberment of

nature by the modern scientific world view and technology. Many of the

analyses, especially when they are the work of feminist authors, indicate

that the destruction and control of nature are to be equated with the

superiority of the masculine principle over the feminine, of the god over

the goddess, in brief with the supremacy of patriarchy. This critical view

of the history of oppression and exploitation of the scientific age has

largely obscured the view of atavistic religions’ hostility towards nature,

especially when these come from the east, like Tibetan Buddhism.

But Buddhist Tantrism, we would like to

unreservedly claim, is hostile to nature and therefore ecologically hostile

in principle, because it destroys

the natural, sensual, and feminine sphere so as to render it useful for the

masculine. Further, in the performance of his enlightenment rituals, every

tantra master burns up all the natural

components of his own human body and, parallel to this (on a macrocosmic

level), the entire natural

universe. From a traditional viewpoint nature consists of a checkered

mixture of the different elements (fire, water, earth, air, ether). In

Tantrism, however, fire destroys the other elementary constituents. In the

final instance it is the “fiery” SPIRIT which subjugates everything else,

but NATURE in particular. Let us recall that Avalokiteshvara, the incarnation father of the Dalai Lama, acts

as the “Lord of Fire” and the Bodhisattva of our age.

Nor were the centers of civilization in

former Tibet at all environmentally friendly. The Lhasa of tradition, for instance, capital of

the Lamaist world, could hardly be described as an exemplary ecological

site but rather, as a number of world travelers have reported, was until

the mid-twentieth century one of the dirtiest cities on the planet. As a

rule, refuse was tipped unto the street. The houses had no toilets.

Everywhere, wherever they were, the inhabitants unburdened themselves. Dead

animals were left to rot in public places. For such reasons the stench was

so penetrating and nauseating that the XIII Dalai Lama felt sick every time

he had to traverse the city. Nobles who stepped out usually held a

handkerchief over their nose.

It is even more absurd to describe the

Tibetan monastic society as a vegetarian culture. The production and

consumption of meat have always been counted among the most important

branches of the country’s economy (not least because of the climatic conditions).

It is indeed true that a devout Tibetan may not kill an animal himself, but

he is not forbidden from eating it. Hence the slaughter is performed by

those of other faiths, primarily Moslems. The Kundun is also a keen meat eater, albeit, if one is to believe

him, not out of enthusiasm but rather for health reasons. Anyone who is

also aware of the great contempt Buddhism in general shows for being reborn

as an animal can only wonder at such eco-paradisiacal-vegetarian

retrospection now on offer in the “scholarly history” of the exiled

Tibetans.

But by now the Tibetans in exile

themselves gladly believe in such ecological fairytales. For them it is

alone the brutal Chinese (whose behavior towards Mother Earth is no better

nor worse than any other capitalist country, however) who are the villains

and stand accused (in this instance rightly) of destroying the ancient

forests of the country and because they pay high prices for aphrodisiacs

won from the bones of the snow leopard. But there are also some factual

objectors to the opinion that the Tibet of old was an eco-paradise. The

Tibetans were never more ecologically aware than other peoples, writes

Jamyan Norbu, co-director of the Tibetan Culture Institute in Dharamsala,

and warns against dangerous myth making (Spiegel, 16/1998, p. 119).

Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian

In this section, which we introduced

with the two German “Greens”, Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian, we would like

to draw attention to some interesting speculations in the Buddhist scene concerning

the reunification of Germany. The Dalai Lama rarely becomes directly and

openly involved in world politics aside from the issue of Tibet unless calling for peace in general.

There are nevertheless numerous occult rumors in circulation among his followers

that suggest him to be the political director of the world who holds the

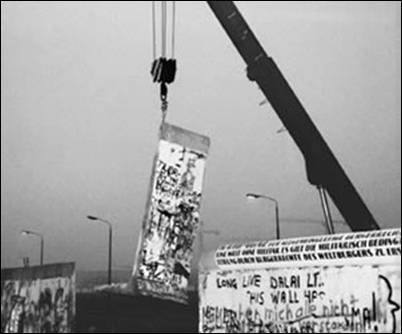

strings from “another dimension” in his hands. For example, there has been

talk that the fall of the Berlin Wall was to be attributed to him. Among

other things, the fact that at the exact point where the first break in the

wall was created (a scene broadcast all around the world) there stood a

graffiti reading Long Live Dalai Lama

is offered as proof of this.

In fact, six months before the German

reunification the Kundun had

stood praying before the “wall of shame” with a candle in his hand. The

pacifist, opponent of atomic energy, environmentalist and committed

campaigner for the freedom of Tibet, Petra Kelly, had been able to

motivate him to cross the East German border together with his entire

retinue in December 1989. After the candle ceremony mentioned, the group

were ferried to a Round Table

discussion with citizens’ rights groups by the GDR state security service

(the infamous Stasi, or secret

police). [2]

The first break in the “fall of the wall”

of Berlin.

See the graffiti “Long live Dalai [Lama]”

Petra Kelly later described the

situation as a political vacuum in which the democratic opposition

presented the vision of transforming the former GDR into a non-aligned

state without a military or nuclear weapons that would align itself with

neither capitalist nor communist ideas. The Dalai Lama was assured that he

would be the first guest of this new state and that Tibet’s autonomy would be recognized as the

first act of foreign affairs. The German participants in this conversation

regarded themselves as a kind of provisional government. All were said to

have been deeply moved by the presence of His Holiness. “Only six months

later, on 22 June 1990", writes Stephen Batchelor, “his prayer was

answered when Checkpoint Charlie was 'solemnly dismounted'"

(Batchelor, 1994, p. 378).

The Dalai Lama as a political magician

who brought down the Berlin Wall with his prayers? Such conceptions lay the

foundations for a “metapolitics” in which international events are

influenced by symbolic actions. Petra Kelly probably thought along these

lines; her extraordinary devotion to the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan cause

is otherwise hard to comprehend.

The pacifist was certainly uninformed

about the Kalachakra Tantra’s

aggressive/warlike core, the androcentric sexual magic of Tibetan Buddhism,

and the dark chapters in the Tibetan and Mongolian history. Like thousands

of others, she followed His Holiness’s charm and messages of peace and was

blind to the gods of the Vajrayana’s

obsessions with power at work through him. As she and her de facto, Gert

Bastian, visited Dharamsala in 1988, they were both, despite having an

eagle eye for every minor infringement of democracy in the German Federal Republic,

“enormously impressed by the extremely democratic discussions” that had

taken place in the parliament of the Tibetans in exile. This was a total

misassessment of the situation — as we have already shown at length and as

anyone who has the smallest insight into the inner political affairs of

Tibetans in exile knows, their popular representation is a farce (Tibetan Review, January 1989, p.

15). But not for Petra Kelly — following her visit to Dharamsala she was so

completely entranced by the Kundun’s

charm and humane political mask that the issue of Tibet became for her the

quintessential “moral touchstone of international politics” (Tibetan Review, July 1993, p. 19).

In concrete terms, that meant the politicians our world stood at a

threshold: if they supported the Dalai Lama they would be following the

path of morality and virtue; if they turned against the Kundun or simply remained passive,

then they would be steering down the road to immorality!

The green politician Petra Kelly

completely failed to perceive the religiously motivated power politics and

the tantric occultism of Dharamsala. Like many other women she became a

female chess piece (a queen) in the Kundun’s

game of strategy, one who opened doors to the German parliament and the

upper political ranks for him.

The illusory world of interreligious dialog and the ecumenical

movement

Although dominated by culturally fixed

images and rituals like every other religion, Tibetan Buddhism initially

presents itself as a tradition that is tied to neither a culture, a

society, nor a race. We hear from every lama that the teachings of the

Shakyamuni Buddha consist exclusively in the experiences of each

individual. Anybody can test their credibility in his or her own religious

practices. Being of another non-Buddhist confession is no obstacle to such

sacred exercises.

This, in the light of the tantric

ritual system and the “baroque” Tibetan pantheon feigned, purist and

liberal basic attitude allows His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama to

present himself as being so tolerant and open minded that he has been

celebrated for years as the “most open minded and liberal ecclesiastical

dignitary” on the planet. His readiness to engage in dialog has all but

become a catchphrase.

In now presenting the Kundun’s interreligious activities,

we always have clearly in mind an awareness that at heart the entire

Lamaist system is and wants to be incompatible with other faiths. Let us

review the reasons for this once more, summarized in seven points. Tantric

Buddhism, especially the Kalachakra

Tantra and the associated Shambhala

myth, includes:

-

The extermination of those of other faiths

-

A warlike philosophy of violence

-

Foundations for a neofascist ideology

-

Contempt for the person, the individual (in favor of the gods),

and especially for women (in favor of the tantra masters)

-

The linking of religious and state power

-

World conquest and the establishment of a global Buddhocracy

via manipulative and warlike means

In the face of these points the Kundun’s ecumenical activity remains

a lie for as long as he continues to abide by the principles of the tantric

ritual system and the ideological/political fundamentals of the Shambhala myth (and the associated

grasp for the world throne). It is nonetheless of important tactical

significance for him and has proved to be an excellent means of spreading

the ideas of Lamaism all over the world without objection.

This indirect missionary method has a long tradition in Tibetan

history. As Padmasambhava (Guru

Rinpoche) won the Land of Snows over to Tantrism in the 8th

century, he never went on a direct offensive by openly preaching the

fundamentals of the dharma. As an

ingenious manipulator, he succeeded in employing the language, images,

symbols, and gods of the local religions as a means of transporting the

Indian Buddhism he had brought with him. The tribes to whom he preached

were convinced that the dharma

was nothing more than a clear interpretation of their old religious

conceptions. They did not even need to give up their deities (even if these

were most cruel) if they were to “convert” to tantric Buddhism, since

Padmasambhava integrated these into his own system.

Even the Kalachakra Tantra, based on a marked and pervasive concept of

the enemy, recommends the manipulation of those of other faiths.

Surprisingly, the “Time Tantra” permits the performance of non-Buddhist

rites by the tantra master. But there is an important condition here,

namely that the mystic physiology of the practicing yogi (his energy body)

with which he controls the entire occult/religious event remain stable and

keep strictly and without deviation to the tantric method (upaya). Then, it says in the time

doctrine, “no form of religion from the way of one’s own or a foreign

people is corrupting for the yogis” (Grünwedel, Kalacakra II, p. 177). With this permission, the way is free

for one to externally appear tolerant and open minded towards any religious

direction without conflicting with the power-political goals of the Kalachakra Tantra and the Shambhala myth that want to elevate

Buddhism to be the sole world religion. In contrast, the feigned “religious

tolerance” becomes a powerful means of surreptitiously promoting one’s own

fundamentalism.

Where does this leave the ecumenical

politics of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama? Interreligious discussions are one

of the Kundun’s specialties;

there is not a major world ecumenical event of significance where his

negotiating presence is not evident. He is one of the presidents of the

“World’s Parliament of Religions” in Chicago. The god-king tirelessly spreads the

happy message that despite differing philosophies all religions have the

same motive, the perfection of humans. „Whatever the differences

between religions,” he explained in Madras in 1985, „all

of them want man to be good. Love and compassion form the essence of any

religion and these alone can bring people together and provide peace and

happiness to humanity” (Tibetan

Review, January 1985, p. 9).

Yet (he says) for the sake of quality

one should not gloss over the differences between the religious approaches.

It is not at all desirable that we end up with a uniform, overarching

religion; that can not be the goal of the dialog. One should guard against

a “religious cocktail”. The variety of religions is a outright necessity

for the evolution of humankind. “To form a new world religion,” the Kundun says, “would be difficult and

not particularly desirable. But since love is essential for all religions,

one could speak of a universal religion of love. Yet with regard to the

methods for developing love and for attaining salvation or permanent

liberation the religions differ from one another ... The fact that there

are so many different depictions of the way is enriching” (Brück and Lai,

1997, p. 520). In general, everyone should stick with the religion he or

she was born into.

For him it is a matter of deliberate

cooperation whilst maintaining autonomy, a dialog about the humanity common

to all. In 1997 the god-king proposed that groups of various religious

denominations undertake a pilgrimage to the holy places of the world

together in order to learn from one another. The religious leaders of the

world ought to come together more often, as “such a meeting is a powerful

message in the eyes of millions of people” (Tibetan Review, May 1997, p. 14).

Christianity

In the meantime, exchange programs

between Tibetan Buddhist and Christian orders of monks and nuns have become

institutionalized through a resolution of the Dalai Lama, with all four

major lines of tradition among the Tibetans (Nyingmapa, Sakyapa, Kagyupa,

and Gelugpa) participating. In the sixties, the American Trappist monk and

poet, Thomas Merton (1906-1968), visited the Kundun in Dharamsala and summarized his experience together as

follows: “I dealt primarily with Buddhists ... It is of incalculable value

to come into direct contact with people who have worked hard their whole

lives at training their minds and liberating themselves from passions and

illusions” (Brück and Lai, 1997, p. 49).

In 1989 the god-king and the

Benedictine abbot Thomas Keating led a gathering of several thousand

Christians and Buddhists in a joint meditation in the West. The Kundun has visited Lourdes and Jerusalem in order to pray there in silent

devotion. There is also very close contact between the Lutheran Church and the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs of H.H. the Dalai Lama.

At the so-called Naropa Conferences

in Boulder, Colorado, topics such as “God” (Christian) and

“Emptiness” (Buddhist), “Prayer” (Christian) and “Meditation” (Buddhist),

“Theism” and “non-Theism”, the “Trinity” and the “Three Body Theory” are

treated in dialog between Christians and Buddhists.

The comparison between Christ and

Buddha has a long tradition (see Brück and Lai, 1997, pp. 314ff.). There

are in fact many parallels (the virgin birth for example, the messianism).

But in particular Mahayana

Buddhism’s requirement of compassion allows the two founding figures to

appear as representatives of the same spirit. Avalokiteshvara, the supreme Bodhisattva of compassion is thus

often presented as a quasi-Christian archetype in Buddhism and also prayed

to as such. This is naturally of great advantage to the Kundun, who is himself an

incarnation of Avalokiteshvara

and can via the comparison (of the two deities) lay claim to the powerful

qualities of Christ’s image.

But His Holiness is extremely cautious

and diplomatic in such matters. For a Buddhist, the Dalai Lama says, Christ

can of course be regarded as a Bodhisattva, yet one must avoid claiming

Christ for Buddhism. (Incidentally, Christ is named in the Kalachakra Tantra as one the

“heretics”.) The Kundun knows

only too well that an open integration of the archetype of Christ into his

tantric pantheon would only lead to strong protests from the Christian

side.

He must thus proceed with more skill if

he wants to nonetheless integrate the Nazarene into his system as

Padmasambhava once incorporated the local gods of Tibet. For example, he describes so many

parallels between Christ and Buddha (Avalokiteshvara)

that his (Christian!) audience arrive at the conclusion that Christ is a

Bodhisattva completely of their own accord.

Just how successful the Kundun is with such manipulation is demonstrated

by a conference held between a small circle of Christians and himself (in

1994), the proceedings of which are documented in the book, The Good Heart: A Buddhist Perspective

on the Teachings of Jesus. In that the god-king repeatedly and emphatically

stressed at this meeting that he had not the slightest intention of letting

Buddhism monopolize anybody or anything, he in fact had the opposite

effect. The more tolerant and respectful towards other religions he showed

himself to be, the more he convinced his listeners that Buddhism was indeed

the one true faith. With this Catch 22, the Dalai Lama succeeded in

emerging at the end of this meeting as a Buddhist super monk, who in

himself combined all the qualities of the three most important Christian monastic

orders: „He [the Dalai Lama] brings three qualities to a spiritual

discourse,” the chief organizer of the small ecumenical event, a

Benedictine, says, „traits so rare in some contemporary Christian circles

as to have elicited grasps of relieved gratitude from the audience. These

qualities are gentleness, clarity, and laughter. If there is something Benedictine about him, there is a Franciscan side as well and a touch

of the Jesuit” (Dalai Lama XIV,

1997, pp. 16–17).

The Kundun appeared to the predominantly

Catholic participants at this interreligious meeting to be more Christian

than the Christians in many points.

Richard

Gere: “Jesus is very much accepted by the Tibetans, even though they don’t

believe in an ultimate creator God. I was at a very moving event that His

Holiness did in

England

where he lectured on Jesus at a Jesuit seminary. When he spoke the words of

Jesus, all of us there who had grown up Christians and had often heard them

before could not believe their power. It was ...” Gere suddenly chokes with emotion.

For a few moments he just stares into the makeup mirror, waiting to regain

his compusere. “When someone can fill such words with the depth meaning

that they are intended to have, it’s like hearing them for the first time.”

(Schell, 2000, p. 57)

Although the Dalai Lama indignantly

rejects any monopolization of other religions by Buddhism, this is not at

all true of his followers. In recent times an ever-expanding esoteric

literature has emerged in which the authors “prove” that Buddhism is the

original source of all religions. In particular there are attempts to

portray Christianity as a variant of the “great vehicle” (Mahayana). Christ is proclaimed as a

Bodhisattva, an emanation of Avalokiteshvara

who sacrificed himself out of compassion for all living creatures (e.g.,

Gruber and Kersten, 1994).

From the Tibetan point of view, the

point of ecumenical meetings is not encounters between several religious

orientations. [3] That would contradict the

entire tantric ritual system. Rather, they are for the infiltration of

foreign religions with the goal (like Padmasambhava) of ultimately

incorporating them within its own system. On rare occasions the methods to be employed in such a

policy of appropriation are discussed, albeit most subtly. Two conferences

held in the USA in 1987 and 1992 addressed the central topic of whether the

Buddhist concept of upaya

("adroit means”) could provide the instrument “for more relaxed

dealings with the issue of truth in dialog (between Christians and

Buddhists)” (Brück and Lai, 1997, p. 281) “More relaxed dealings with the

issue of truth” — that can only mean that the cultic mystery of the sexual

magic rites, the warlike Shambhala

ideology, and the “criminal history” of Lamaism is either not mentioned at

all at such ecumenical meetings or is presented falsely.

An 800-page work by the two theologists

Michael von Brück and Whalen Lai (Buddhismus

und Christentum [Buddhism and Christianity]) is devoted to the topic of

the encounter between Buddhism and Christianity. In it there is no mention

at all of the utmost significance of Vajrayana

in the Buddhist scene, as if this school did not even exist. We can read

page after page of pious and unhurried Mahayana

statements by Tibetan lamas, but there is all but nothing said of their

secret tantric philosophy. The terms Shambhala

and Kalachakra Tantra are not to

be found in the index, although they form the basis for the policy on

religions of the Dalai Lama whom the authors praise at great length as the

real star of the ecumenical dialog. We can present this “theologically”

highbrow book as evidence of the subtle and covert manipulation through

which the “totalistic paradigm” of Tibetan Buddhism is to be anchored in

the west.

Only at one single incriminating point,

which we have already quoted earlier, do the two authors let the cat out of

the bag. In it they recommend that American intellectuals who feel

attracted to Chinese Hua-yen Buddhism should instead turn to the Kundun as the only figure in a

position to be able to establish a Buddhocracy: “Yet Hua-yen is no longer a

living tradition. ... That does not mean that a totalistic paradigm could not be repeated, but it seems

more sensible to seek this in the Tibetan-Buddhist

tradition, since the Tibetan Buddhists have a living memory of a real

'Buddhocracy' and a living Dalai Lama who leads the people as a religious and political head” (Brück and Lai,

1997, p. 631). The authors thus believe, despite pages of feigned

ecumenical Christianity, that a “totalistic paradigm” could be repeated in

the future and recommend the god-king from Dharamsala as an example. They

thus clearly and openly confirm the Buddhocratic vision of the Kalachakra Tantra and the Shambhala myth, of which they

themselves have not breathed a word.

The Kundun

even seems to have succeeded in gaining access to the “immune” Judaism.

After the Dalai Lama’s visit to Jerusalem (in 1996), groups were formed in

Israel and the USA in which Jewish and Buddhist ideas were supposed to be

brought together. A film has been made about the fate of the Israeli writer

Rodger Kamenetz, who converted to Buddhism after he had visited the Dalai

Lama in Dharamsala and then set about reinterpreting his own religious

roots in Buddhist terms. The so-called Bu-Jews

(Buddhist Jews) are the most recent product of the Kundun’s politics of tantric conquest. They are hardly likely

to be aware of the interlinkage between Tantric Buddhism and occult fascism

that we have described in detail.

Islam (The Mlecchas)

In contrast Islam is proving more

difficult for His Holiness than the Jews and Christians: “I can barely

recall having a serious theological discussion with Mohammedans”, he said

at the start of the eighties (Levenson, 1992, p. 288). This is only all to

readily understandable in light of the apocalyptic battle between the Mlecchas (followers of Mohammed) and

the Buddhist armies of the mythical general, Rudra Chakrin, prophesied in the Shambhala myth. A foretaste of this radical confrontation,

which according to the Kalachakra

prophecy awaits us in the year 2327, was to be detected as the Moslem

Taliban in Afghanistan declared in 1997 that they would destroy the

2000-year-old statues of Buddha in Bamyan because Islam prohibited human

icons. This could, however, be prevented under pressure from the world

public who reacted strongly to the announcement. (We would like to mention

in passing that the likenesses of Buddha carved into the cliffs of Bamyan,

of which one figure is 60 yards high, are to be found in a region from

which, in the opinion of reliable investigators like Helmut Hoffmann and

John Ronald Newman, the Kalachakra

Tantra originally comes.)

However, after being awarded the Nobel

peace prize, the Kundun in his

function as a world religious leader has revised his traditional

reservation towards Islam. He knows that it is far more publicity-friendly

if he also displays the greatest tolerance in this case. In 1998, he thus

encouraged Indian Muslims to play a leading role in the discourse between the

world religions. In the same, conciliatory frame of mind, in an interview

he earlier expressed the wish to visit Mecca one day (Dalai Lama XIV,

1996b, p. 152). [4]

On the other hand however, His Holiness

maintains very close contact with the Indian BJP (Bhatiya Janata Party) and the RSS (Rashtriya Svayam Sevak Sangh), two old-school conservative Hindu organizations

(currently — in 1998 — members of the governing coalition) who proceed with

all vigor against Islam. [5]

An honest renunciation of Tantric

Buddhism’s hostility toward Islam could only consist in the Kundun’s clear distantiation from

all the passages from the Kalachakra

tradition that concern this. To date, this has — as far as we know — never

happened.

In contrast, already today there are radical

developments in the Buddhist camp that are headed for a direct

confrontation with Islam. For example, the Western Buddhist “lama”, Ole

Nydhal (a Kagyupa), is strongly

and radically active in opposition to the immigration of Moslems to Europe.

As problematic as we perceive

fundamentalist Islam to be, we are nonetheless not convinced that the Kalachakra ideology and the final

battle with the Mlecchas

(Mohammedans) prognosticated by the tantra can solve the conflict at the

heart of the struggle between the cultures. A contribution to an

internet-based discussion rightly described the idea of a Shambhala warrior as the Buddhist

equivalent to the jihad, the

Moslem “holy war”. Religious wars, which have the goal of eliminating the

respective non-believers, have in fact, and for the West unexpectedly,

become a threat to world peace in recent years. We return to this point in

our conclusion, especially the question of whether the division of humanity

into two camps — Buddhist and Islam — as predicted in the Kalachakra Tantra is just a fiction

or whether it is a real danger.

Shamanism

Up until well into the eighties, the

encounter with nature religions played a significant role for the Dalai Lama. There was at that stage

a lot of literature that enthusiastically drew attention to the parallels

between the North American culture of the Hopi Indians and Tibetan

Buddhism. The same terminology was even discovered, just with the meanings

reversed: for example, the Tibetan word for “sun” was said to mean “moon”

in the language of the Hopi and vice versa, the Hopi sun corresponded to

the Tibetan moon (Keegan, 1981, unnumbered). There are also said to be

amazing correspondences among the rituals, especially the “fire

ceremonies”.

For a time the idea arose that the

Dalai Lama was the messiah announced in the Hopi religion. In the legend

this figure had been a member of the “sun clan” in the mythical past and

had left his Indian brothers so as to return in the future as a redeemer. “They

wanted to tell me about an old prophecy of their people passed on from

generation to generation,” His Holiness recounted, “in which one day

someone would come from the east. ... They thought it could be me and had

come to tell me this” (Levenson, 1992, p. 277).

In France in 1997 an unusual meeting

took place. The spiritual representatives of various native peoples

gathered there with the intention of founding a kind of international body

of the “United Traditions” and presenting a common “charta” to the public.

By this the attendees understood a global cooperation between shamanistic

religions, still practiced all over the world, with the aim of articulating

common rights and gaining an influence over the world’s conscience as the

“circle of elders”. The Dalai Lama was also invited to this congress,

organized by a Lamaist monastery in France (Karma Ling). Just how adroitly the organizers made him the

focal figure of the entire event, which was actually supposed to be a union

of equals, is shown by the subtitle of the book subsequently published

about the event, The United

Traditions: Shamans, Mecidine Men and Wise Women around the Dalai Lama.

The whole scenario did in fact revolve around the Dalai Lama. Siberian

shamans, North, South, and Central American medicine men (Apaches,

Cheyenne, Mohawks, Shuars from the Amazon, and Aztecs), African voodoo

priests (from Benin),Bon lamas, Australian Aborigines, and Japanese martial

artists came together for an opening ceremony at a Vajrayana temple,

surrounded “by the amazing beauty of the Tibetan décor” (Eersel and

Grosrey, 1998, p. 31). The meeting was suddenly interrupted by the cry,

“His Holiness, His Holiness!” — intended for the Dalai Lama who was

approaching the meeting place. The shamans stood up and went towards him.

From this point on he was the absolute center of events. There were

admittedly mild distantiations before this, but only the Bon priests dared

to be openly critical. Their representative, Lopön Trinley Nyima Rinpoche,

strongly attacked Lamaism as a repressive religion that has persecuted the

Bon followers for centuries. In answer to a question about his attitude to

Tibetan Buddhism he replied, “Seen historically, a merciless war has in

fact long been conducted between us two. … Between the 7th and the 20th

century a good four fifths of Tibet was Buddhist. Sometimes this also meant

violence: hence, in the 18th century, with the help of the Chinese, the

Gelugpa carried out mass conversions in the border regions of Tibet which

had long been inhabited by the Bon” (quoted by Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p.

141). Still today, the Bonpos are disadvantaged in many ways: “You should

be aware, for instance, that non-Buddhist children do not see a penny of

the money donated by international aid organizations for Tibetan children!”

Nyima Rinpoche protested (quoted by Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p. 132).

But the Kundun knows how to deal with

such matters. The next day he lets the Bon critic sit beside him, and

declares the Bonpos to be “Tibet’s fifth school”. In his pride, Nyima

Rinpoche forgot about any criticism or the history of the repression of his

religion. The Dalai Lama takes the African voodoo representative, Daagpo

Hounon Houna, in his arms and has a photo taken. The two book authors

comment that, “Back home in Africa this picture will certainly receive

great symbolic status” (Eersel and Grosley, 1998, p. 132). Then the Kundun

says some moving words about “Mother Earth” he has learned from the New Age

milieu and which as such do not exist in the Tibetan tradition: “These days

we have too little contact to Mother Earth and in this we forget that we

ourselves are a part of nature. We are cildren of nature, Mother Earth, and

this planet is our only home” (quoted by Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p. 180).

Let us recall that before the start of every Kalachakra ritual the earth spirits are nailed down with a

ritual dagger. The Dalai Lama goes on to preach about the variety of races

and the equality of the religions of the world. And he has already won the

hearts of all. It is naturally his congress,

he is the axis around which the “circle of elders” revolves.

Roughly in the middle of the book we

suddenly learn that the delegates were invited in his name and that “without the support and the

exceptional aura of His Holiness” nothing would have been possible (Eersel

and Grosrey, 1998, p. 253). Even the high priest from Benin, who smuggled

the remains of an animal sacrifice into the ritual temple that was,

however, discovered and removed, accepts the Tibetan hierarch as the

central figure of the meeting, saying “I therefore greet His Holiness the

Dalai Lama around whom we have gathered here” (Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p.

199). One of the organizers(Jean-Claude Carrière) sums things up: “That was

actually the motor of this meeting. Here for the first time peoples, some

of whom have almost vanished from the face of the earth, were asked to

speak (and act) and they have recognized the likewise degraded, disowned,

and exiled Dalai Lama as one of their own. It is barely imaginable how

important it was for them to be able to bow before him and present him with

a gift” (Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p. 254). Tibetan Buddhism is becoming a

catch-all for all religions: “If the meeting of the United Traditions took

place in a Buddhist monastery, it is surely because the spirit of the Way

of Buddha, as embodied by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, encourages such

meetings. His presence alongside the elders and the role of unifier which

was accorded him on the Day of the United Traditions, is in the same

category as the suggestions that he made in front of the assembled

Christians in 1994 …” (Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p. 406). Thus Lamaism

plays the tune to which those attending dance: “A more astonishing vision,

in which we here, borne along by the songs and drums of the Tibetans, begin

to ‘rotate’ along with the Asian shamans, African high priests, American

and Australian men and women of knowledge” (Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p.

176).

This meeting made two things apparent:

firstly, that the traditions of the native peoples are fundamentally

uninterested in a process of criticism or self-criticism, and secondly,

that here too the Dalai Lama assumes spiritual leadership as a “king

shaman”. A line from the joint closing prayer typifies the androcentric

spirit of the “circle of elders”: “God our Father, we sacrifice and

dedicate to you our Mother the Earth” (Eersel and Grosrey, 1998, p. 413).

This says it all; even if a few women participate the council of elders

remains a “circle of patriarchs”, and the female sacrifice which we have

identified as the central mystery of Tantric Buddhism also essentially

determines the traditional systems of ritual of the shamans gathered in

France.

The occult scene and the

New Age

What then is the relationship like

between the Dalai Lama and the so-called esoteric scene, which has spread

like a bomb all over the West in

recent years? In relations with various traditional occult sects (the

Moonies, Brahmakumaris, Scientologists, Theosophists, Roerich groups) who

in general do not enjoy a good name in the official press His Holiness is

often more tolerant and intimate than the broad public realizes. We have

already reported extensively about his connection to Shoko Asahara’s AUM

sect. He also maintains lively contact with Theosophists of the most

diverse schools. A few years ago His Holiness praised and introduced a

collection of Madame Blavatsky’s writings with a foreword.

But it is his relationship with the

religious subculture that became known worldwide as the New Age Movement which is of

decisive significance. Already at the start of the seventies the youth

protest movement of 1968 was replaced by the spiritual practices of

individuals and groups, the left-wing political utopia of a classless

society by a vision of the “community of the holy”. All the followers of

the New Age saw themselves as

members of a “soft conspiracy” that was to prepare for the “New Age of

Aquarius” and the appearance of messianic saviors (often from non-European

cultures). Every conceivable school of belief, politico-religious viewpoint

and surreal fantasy was gathered up in this dynamic and creative cultural

current. At the outset the New Age

movement displayed a naive but impressive independence of the existing

religious traditions. It was believed one could select the best from all cultic mysteries —

those of the Indians and American Indians, the Tibetans, Sufis, the

Theosophists, etc. — in order to nonchalantly combine it with one’s own

spiritual experiences and further develop it in the sense of a spiritual

and peaceful global community. Even traditionally based gurus from the

early phase like Rajneesh Baghwan from India or the Tibetan, Chögyam

Trungpa, were able to accept this “spiritual liberalism” and combined their

hallowed initiation techniques with all manner of methods drawn from the

modern western tradition, especially with those of therapeutic psychology.

But after only a few years of creative freedom, the orthodox ecclesiastical

orientations and atavistic sects who put this “mystic-original potential”

to use for their own ends, indeed vitally needed it for their own

regeneration, prevailed in the New

Age movement.

Buddhism was intensively involved in

this process (the incorporation of the New

Age) from the outset. At first the influence of Japanese Zen

predominated, however, two decades later Tibetan Lamaism succeeded in

winning over ever more New Age

protagonists. The fact that since the 19th century Tibet has

been the object of western fantasies, onto which all conceivable occult

desires and mystic hopes have been projected, certainly helped here. The

Theosophic vision of omnipotent Mahatmas

who steer the fate of the world from the heights of the Himalayas has

developed into a powerful image for non-theosophical religious subcultures

as well.

For the Fourteenth Dalai Lama the New Age Movement was both the

primary recruiting field for western Buddhists and the gateway to

mainstream society. The double character of his religion, this mixture of

Buddhocratic officialese and the anarchistic drop-out that we have depicted

earlier, was of great advantage to him in his skilled conquest of the

spiritual subculture. Then the “children of the Age of Aquarius”, who

conceived of themselves as rebels against the existing social norms (their

anarchic side) and were not infrequently held up to ridicule by the

bourgeois public, also on the other hand battled fiercely for social

recognition and the assertion of their ideas as culturally acknowledged

values. A visit by the Dalai Lama lent their events considerable official

status, which they would not otherwise have had. They invested much money

and effort to achieve this. Since the Dalai Lama was only very rarely

received by state institutions before the late eighties but nonetheless saw

extended travels as his political duty, the material resources of the New

Age scene likewise played an important role for him. “He opens Buddhist

centers for New Age nouveau riche protagonists”,

wrote the Spiegel, “whose

respectability he cannot always be convinced about” (Spiegel 16/1998, p. 111). Up until the mid eighties, it was

small esoteric groups who invited him to visit various western countries

and who paid the bills for his expenses afterwards — not the ministers and

heads of state in Bonn, Madrid, Paris, Washington, London, and Vienna.

Such an arrangement suited the

governments well, since they did not have to risk falling out with China by

committing themselves to a visit by the Dalai Lama. On the other hand, the

exotic/magic aura of the Kundun, the

“living Buddha” and “god-king”, has always exercised a strong attraction

over Society. Hardly anyone who had a name or status (whether in business,

politics, the arts, or as nobility) could resist this charming and “human”

arch-god. To be able to shake the hand of the “yellow pontiff” and

“spiritual ruler from the roof of the world” and maybe even chat casually

with him has always been a unique social experience. Thus, on these

somewhat marginalized New Age

trips, time and again “secret” meetings took place “on the side “ with the

most varied heads of state and also very famous artists (Herbert von

Karajan for example), who let themselves be enchanted by the smile and the

exoticism of the Kundun.

Countless such unofficial meetings laid the groundwork for the Kundun’s Great Leap into the

official political sphere, which he finally achieved at the end of the

eighties with the Tibet Lobby and

the award of the Nobel peace prize (1989).

Since then, it has been the heads of

state, the famous stars, the higher ranks of the nobility, the rectors of

the major universities, who receive the Tibetan Kalachakra master with much pomp and circumstance. The

intriguing, original but naive New

Age Movement no longer exists. It was rubbed out between the various

religious traditions (especially Buddhism) on one side and the “bourgeois”

press (the so-called “critical public”) on the other. For all the problems

this spiritual heir and successor to the movements of 1968 had, it also

possessed numerous ideas and life practices which were adequate for a

spiritually based culture beyond that of the extant religious traditions.

But the bourgeois society (from

which the “Children of the Age of Aquarius came) had neither recognized nor

acted upon this potential. In contrast, the traditional religions, but

especially Buddhism, reacted to the New

Age scene with great sensitivity. They had experienced the most

dangerous crisis in their decline in the sixties and they needed the

visions, the commitment, and the fresh blood of a young and dynamic

generation in order to survive at all. Today the New Age is passé and the Kundun

can distance himself ever further from his old friends and move over into

the establishment completely.

In the following chapter we shall show

just how decisive a role the Kundun

played in the conservative process of resorption (of the New Age). He succeeded, in fact, in

binding the intellectual and scientific elite of the New Age Movement to his own atavistic system. These were both

young and elder western scientists trained in the classic disciplines

(nuclear physics, chemistry, biology, neurobiology) who endeavored to

combine their groundings in the natural sciences with religious and

philosophical presentations of the subject, whereby the Eastern-influenced

doctrines became increasingly important. This international circle of bold

thinkers and researchers, who include such well-known individuals as Carl

Friedrich von Weizsäcker, David Bohm, Francisco Varela, and Fritjof Capra,

is our next topic. A further section of the New Age scene now serve as his dogsbodies through their

commitment to the issue of Tibet, and are spiritual rewarded from time to

time with visits from lamas and retreats.

Modern science and Tantric Buddhism

In 1939 in a commentary on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the great

psychologist Carl Gustav Jung wrote to the effect that to practice yoga on

the 5th Avenue or anywhere else that could be reached by telephone would be

a spiritual joke. Jung was convinced that the ancient yoga practices of

Tibetan Tantrism was incompatible with the modern, scientifically and

technologically determined, western world view. For him, the combination of

a telephone and Tibet presented a paradox. “The telephone! Was there no

place on earth where one could be protected from the curse”, a west

European weary of civilization asks in another text, and promptly decides

to journey to Tibet, the Holy Land, in which one can still not be reached

by phone (Riencourt, 1951, pp. 49-50). Yet such yearning western images of

an untouched Tibet are deceptive. Just one year after Jung’s statement (in

1940) the Potala had its own telephone line.

But there were also other voices in the

thirties! Voices that dared to make bold comparisons between modern

technical possibilities and the magic powers (siddhis) of Tantrism: Evans-Wentz, for example, the famous

translator of the Tibetan Book of the

Dead, enthuses about how “As from mighty broadcasting stations, the Great

Ones broadcast over the earth that Vital Spirituality which alone makes

human evolution possible” (Evans-Wentz, 1978, p. 18). These “Great Ones”

are the Maha Siddhas ("Grand

Sorcerers”) who are in hiding in the Himalayas (in Shambhala) and can with their magic reach out and manipulate

every human brain as they will.

In the last thirty years Tibetan

Buddhism has built up a successful connection to the modern western age.

From the side of the “atavistic” religion of Tibet there is no longer any

fear of contact with the science and technology of the West. All the

information technologies of the Occident are skillfully and abundantly

employed by Tibetan monks in exile and their western followers. There are

countless homepages preaching the dharma

(the Buddhist teaching) on the internet. The international jet set includes lamas who fly

around the globe visiting their spiritual centers all over the world.

But Tibetan Buddhism goes a step

further: the monastic clergy does not just take on the scientific/technical

achievements of the West, but attempts to render them epistemologically

dependent on its Buddhocratic/tantric world view. Even, as we shall soon

show, the Kundun is convinced

that the modern natural sciences can be “Buddhized”. This is much easier for

the Buddhists than the Moslems for example, who are currently pursuing a

similar strategy with western modernity. The doctrine of Mohammed is a

revelatory religion and has been codified in a holy book, the Koran. The Koran is considered the absolute word of God and forms the

immutable foundation of Islamic culture. It proves itself to be extremely

cumbersome when attempts are made to subsume the European scientific

disciplines within this revelatory text.

In contrast, Tibetan Buddhism (and also

the Kalachakra Tantra) is based

upon an abstract philosophy of “emptiness” which as the most general of

principles can “include” everything, even western culture. “Everything arises out of shunyata (the emptiness)!” — with

this fundamental statement, which we still have to discuss, the Lamaist

philosophical elite gains access to the current paradigm discussion which has had European science holding its

breath since Heisenberg’s contribution to quantum theory. What does this

all mean?

„Paradigms gain their status,” Thomas Kuhn writes in his classic

work, The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions, „because they are more successful than their competitors

in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners has come to

recognize as acute.” (Kuhn, 1962, p. 23). In his statement, Kuhn takes a scientific paradigm dispute (between

“theories”) as his starting point, but at the same time opens the door for articles of faith, since in his

investigation a paradigm does not need to explain all its assumptions. In very general terms, we can thus

understand the basic foundations of a human culture, be they of a

scientific or a religious nature, as a paradigm. The dogma as to whether it

is a god or a goddess who stands at the beginning of creation is thus just

as much a paradigm as René Descartes’ assumption of the separation of the

thinking mind (res cogitans) from

extended matter (res extensa), or

the principle of natural causation of Newtonian physics. Just like the

believers in the tantric Shambhala

myth, traditional Christians who accept the doctrinal status of the

Apocalypse of St. John interpret human history according to an eschatological, intentional

paradigm. In both systems, all historical events are directed towards a

final goal, namely the coming of a messiah (Christ or Rudra Chakrin)

and the staging of a final battle between believers and unbelievers. The

future of humanity is thus fixed for all time. In contrast, western

historicism sees history purely as the interplay of various causes that

together produce an open-ended, undecided future. It thus follows a causal paradigm. A democracy holds

the principle of the freedom and equality of all people as its guiding

paradigm, whereas a theocracy or Buddhocracy recognize the omnipotence of a

god or, respectively, Buddha as the highest principle of their system of

governance.

New paradigms first come to the fore in

a society’s cultural awareness when the old dominant paradigmatic

fundamentals come into crisis. The western world is currently being shaken

by such a paradigmatic crisis. According to contemporary critics, the

scientific “Age of Reason” in alignment with the ideas of René Descartes

and Isaac Newton is no longer able to cope with the multiplex demands of a

postmodern society. Neither is the mechanistic world view with the causal

principle of classical physics sufficient to apprehend the complexity of

the universe, nor does western “rationalism” help meaningfully organize human and natural life. “Reason” for

instance, as the undisputed higher principle reigned over the emotions,

intuition, vision, religiousness, erotic love, indeed even over humanism.

The result has been a fundamental crisis of meaning and epistemology.

Citing Oswald Spengler, some commentators talk of the Fall of the West.

Hence proposals for the new,

“postmodern” paradigms of the third millennium have been discussed

everywhere in recent years at conferences and symposia (not least in New Age circles). For example,

rather than trying to explain nature through linear-causal models, as in

Newtonian physics, one can consider holistic, synchronic, synergetic,

ecological, cybernetic, or micro/macrocosmic structures.

Such new models revolutionize

perception and thought and are easier to name than to put into socially

integrated practice. For a paradigm shapes reality as such to conform with its foundations, it

“objectifies” it, so to speak, in its image; in other words (albeit only

after it has been culturally accepted) it creates the “objective world of

appearances “, that is, people perceive reality

through the paradigmatic filter of their own culture. A paradigm shift is

thus experienced by the traditional elements of a society as a kind of loss

of reality.

For this reason, as the foundations of

a culture paradigms are not so easily shaken. In order to abandon the

“outdated” Newtonian world view of classical physics, for example, the

reality-generating bases of its thinking (above all the causal principle)

would have to be relativized. But this — as Kuhn has convincingly argued —

does not necessarily require that the new (postmodern, post-Newtonian)

paradigm deliver an updated and more convincing scientific proof or a rational explanation, rather, it is

sufficient for the new world view to appear

better in total than the old one. To put it bluntly, this means that it is

the most powerful and not

necessarily the most reasonable paradigm

that after its cultural establishment becomes the best and is thus accepted as the basis of a new culture.

Hence every paradigm change is always

preceded by a deadly power struggle between various world views. Deadly

because once established, the victorious paradigm completely disables its

opponents, i.e., denies them any paradigmatic (or reality-explaining)

significance. Ptolemy’s cosmological paradigm ("the sun rotates around

the earth”) no longer has, after Copernicus ("the earth orbits the

sun”), any reality-generating meaning. Thus, in the Copernican era the

Ptolemaic views are at best considered to still be imaginary truths but are

no longer capable of explaining reality.

To take another example — for a Tibetan lama, what a positivist scientist

refers to as reality is purely illusory (samsara), whilst the other way around, the religious world of

the lama is a fantastic, if not outright pathological illusion for the

scientist.

The crisis of western modernity (the

rational age) and the occidental discussions about a paradigm shift

primarily have nothing to do with Buddhism, they are a cultural event that

arose at the beginning of the twentieth century in scientific circles in

Europe and North America and a result of the critical self-reflection of

western science itself. It was primarily prominent representatives from

nuclear physics who were involved in this process. (We shall return to this

point shortly.) Atavistic religious systems with their questionable wisdoms

are now pouring into the “empty” and “paradigmless” space created by the

self-doubt and the “loss of meaning “ of the modern western age, so as to

offer themselves as new paradigms and prevail. In recent decades they have

been offering their dogmas (which were abandoned during the Enlightenment

or “age of reason”) with an unprecedented carefree freshness and freedom,

albeit often in a new, contemporary packaging.

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama is just one

of many (coming from the East) who present themselves and their spiritual

meaning to the West as its savior in great need, but he is particularly

adroit at this. Of course, neither the sexual magic doctrines of the Kalachakra Tantra nor the military

ideology of the Shambhala myth

are to be found in his public teachings

(about the new paradigm), just the epistemological discourse of the two

most important Buddhist philosophical schools (Madhyamika and Yogachara)

and the compassionate, touching ethic of Mahayana Buddhism.

One must, however, admit without

reservation that the Buddhist epistemological doctrine makes its entry into

the western paradigm discussion especially easy. No matter which school,

they all assume that an object is only manifest with the perception of the object.

Objectivity (reality) and

subjective perception are thus inseparable, they are in the final instance

identical. This radical subjectivism necessarily leads to the philosophical

premise that all appearances in the exterior world have no “inherent

existence” but are either produced by an awareness (in the Yogachara school) or have to be

described as “empty” (as in the Madhyamika

school).

We are dealing here with two

epistemological schools of opinion which are also not unknown in the West.

The Buddhist Madhyamika

philosophy, which assumes the “emptiness” (shunyata) of all being, could thus win for itself a substantial

voice in the Euro-American philosophical debate. For example, the thesis of

the modern logician, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), that all talk of

“God” and the “emptiness” is nothing more than “word play”, has been

compared with the radical statement of the Madhyamika scholar, Nagarjuna (2nd to 3rd

century), that intellectual discourse is a “word play in diversity” (Brück

and Lai, 1997, p. 443). [6]

Further, the Yogachara school ("everything is awareness”) is presented

as a Buddhist witness for the “quantum theory” of Werner Heisenberg

(1901-1976). The German nuclear physicist introduced the dependence of

“objective” physical processes upon the status of an (observing) subject

into the scientific epistemological debate. Depending upon the experimental

arrangement, for example, the same physical process can be seen as the

movement of non-material waves or as the motion of subatomic particles (uncertainty principle). Occult

schools of all manner of orientations welcomed Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle as a

confirmation of their proposed spiritualization (subjectification) of all

being and celebrated his observations as a “scientific” confirmation of

their “just spirit” theories. ("Reality is dependent on the observing

subject”).

Even the

Fourteenth Dalai Lama speaks nonchalantly

about Heisenberg’s theory and the subjectivity of atomic worlds: „Thus

certain phenomena in physics”, we hear from the man himself, „are sometimes

described as electromagnetic waves and on other occasions as particles. The

description of the phenomenon thus seems to be very dependent upon the describer.

Thus, in science we also find this concrete relationship to spirit, to the

observing spirit which attempts to describe the phenomenon. Buddhism is

very rich regarding the description of the spirit ... „ (Dalai Lama XIV,

1995, p. 52).

Surprisingly,

such epistemological statements by the Kundun,

which have in the meantime been taken up by every esoteric, are taken

seriously in scientific circles. Even eminent authorities in their subject

like the German particle physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von

Weizsäcker who was one of the leading theoretical

founding fathers of the atomic bomb are enthusiastic about the

self-assurance with which the god-king from Tibet chats about topics in

quantum theory, and come to a far-reaching conclusion: „I [von Weizsäcker]

therefore believe that modern physics is in fact compatible with Buddhism,

to a higher degree than one may have earlier imagined” (Dalai Lama XIV,

1995, 11).

On the other

hand, in a charming return gesture the Kundun

describes himself as the „pupil of Professor von Weizsäcker. ... I myself

regard ... him as my teacher, my guru” (Dalai Lama XIV, 1995, p. 13), and

at another point adds,

“The

fact is that the concepts of atoms and elementary particles is nothing new

for Buddhism. Since the earliest times our texts speak of these and mention

even more subtle particles. ... After numerous conversations with various

researchers I have realized that there is an almost total correspondence