|

March 30, 2013

from

TheAtlantic Website

It's the gold standard...

minus the shiny

rocks.

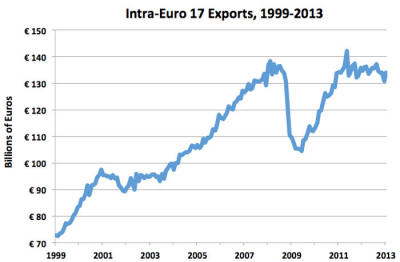

We're going to need a bigger acronym. In the beginning, it was just the "Greek debt crisis". Then markets realized Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain were in bad shape too, and the PIIGS (or GIIPS) were born.

But now Cyprus and Slovenia have run into trouble as well, giving us the... SIC(K) PIGS? At this rate, we're going to have to buy a vowel soon, assuming Estonia doesn't end up needing a bailout. The Euro crisis is entering its fourth year, and, sorry world, this won't be its last. Now, its long periods of boredom have gotten a bit longer, and its moments of sheer financial terror a bit less terrifying ever since the European Central Bank (ECB) promised to do "whatever it takes" to save the common currency.

But, as Cyprus and Slovenia

show, the battle for the Euro isn't over yet. Not even close. Here's the Cliff Notes version of the Euro crisis. The Euro zone doesn't have the fiscal or banking unions it needs to make monetary union work, and it's not close to changing that. In the meantime, the euro's continuing flaws continue to suck countries into crisis. And their politics get radicalized.

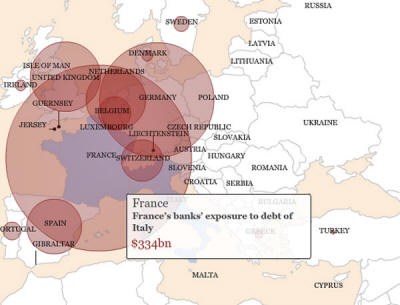

Most recently, Cyprus was forced to accept a bailout and bail-in, because its too-big-to-save banks made some horrendously bad bets on Greek bonds.

Slovenia looks like it could next on the Euro-bailout tour, because, as Dylan Matthews of the Washington Post points out, its too-big-to-save-ish banks made some horrendously bad bets on its own companies. Now, banks make bad bets all the time, but those bad bets can bankrupt you as a country if you don't have your own central bank. Like Euro countries. Of course, this "diabolic loop" between weak banks and weak sovereigns isn't the only problem in Euroland. The common currency has plenty of other flaws.

Here's why the Euro, as it's currently constructed, is a doomsday device for mass bankruptcy. (How's that for solidarity?).

The Euro is the gold standard minus the shiny rocks.

Both force countries to give up their ability to fight recessions in return for fixed exchange rates and open capital flows. But giving up the ability to fight recessions just makes it easier for recessions to turn into depressions.

And that puts all of the pressure on wages to adjust down when a shock hits - the most painful and destructive way of doing things. But the gold standard had an even bigger design flaw than creating depressions. That was perpetuating depressions. Under the rules of the game, countries short on gold were supposed to raise interest rates, which would push down wages, and push up exports. More exports would mean more gold, and then lower interest rates.

But there was an asymmetry.

Countries needed gold to create money, but countries didn't need to create money if they had gold. During the Great Depression, the U.S. and France sucked up most of the world's gold, but didn't turn it into money out of fear of nonexistent inflation.

Countries that needed gold needed to push down wages even more to make their exports competitive - not that there were any booming markets for them to export to, due to the self-inflicted economics wounds of the U.S. and France. Instead, the depression just fed on itself. The Euro suffers from a similar asymmetry. Debtor-Euro countries are to cut wages and deficits, but creditor-Euro countries aren't forced to increase wages and deficits. Perversely, the opposite. In other words, northern Europe isn't doing enough to offset the demand destruction in southern Europe. And it's sinking them all.

Even worse, this slow-motion collapse is turning loans that would have otherwise been good into losses - losses that force bailouts and faster collapses. But, to be clear, this isn't only a problem for the periphery.

As the U.S. and France found out in the

1930s, it's generally not a good idea to force your customers into

bankruptcy. That just creates depression without end - until the gold

(or Euro) standard ends. It's no coincidence that the countries that

ditched the gold standard first recovered from the Great Depression

first. History doesn't need to repeat, or even rhyme. Europe doesn't have to keep crucifying itself on a cross of Euros, the gold standard of the 21st-century.

The euro's northern bloc could decide to let the ECB do more. Or it could decide to start spending more. Or not.

Eurocrats seem content to do just enough to keep everything from falling apart, and nothing more. It's one part inflationphobia, and another part strategy.

Indeed, it's how they try to keep the pressure on the southern bloc to push through unpopular labor market reforms. But doing enough today eventually won't be enough tomorrow if the southern bloc doesn't have any hope of recovering within the Euro.

The politics will turn against the common currency long before that. By that point, Europe won't need an acronym anymore.

|