|

August 08, 2017 from WorldPoliticsReview Website

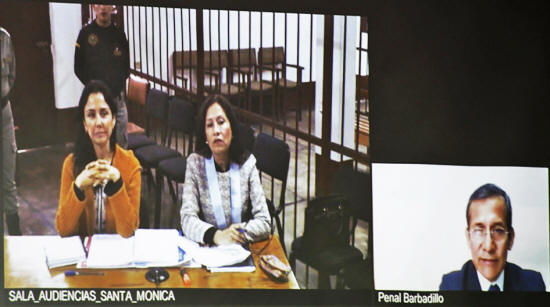

who are under preventative detention, attend a court hearing via video link, Lima, Peru, July 31, 2017 (AP photo by Martin Mejia).

Peru's political

establishment has been shaken by investigations and allegations of

corruption, with one former president and his wife jailed while

prosecutors investigate charges of money laundering against them,

and another former president facing possible extradition from the

U.S. in a similar case. What began as several national investigations into suspicious bank transfers and real estate purchases gained urgency following revelations from Brazil about an international bribery network managed by the construction conglomerate Odebrecht.

The company's

executives have admitted to

paying approximately $800 million in bribes

to public officials in a dozen countries in order to obtain billions

of dollars' worth of government contracts.

In February, the

former director of

Odebrecht in Peru, Jorge

Barata, told investigators that Odebrecht donated $3 million to

Humala's 2011 election campaign, which Humala and Heredia deny.

During an appeal

hearing last week, the couple denied having done anything to hinder

the investigation and claimed the decision to jail them was

politically motivated.

Peruvian prosecutors are investigating the purchase of approximately $4.6 million worth of real estate in Lima by Toledo's mother-in-law.

The purchases were made with funds from a company in Costa Rica called Ecoteva, which was founded by Toledo's friend Josef Maiman, a Peruvian-Israeli businessman.

Toledo, who denies

any wrongdoing, claims that his mother-in-law bought the properties

as an intermediary for Maiman, for whom Peru has issued an

international arrest warrant, though INTERPOL has been unable to

locate him.

Construction of that roadway, which connects southern Peru with Brazil, ended up costing $4.5 billion, several times the original bid.

Toledo has denied taking bribes and threatened to sue Barata for defamation.

Meanwhile, former President Alan Garcia, whose 2006-2011 administration awarded Odebrecht contracts for major public works, spent several hours this week answering prosecutors' questions about the construction of a commuter train line known as Metro 1.

Several officials from Garcia's administration have been jailed as part of an investigation sparked by Odebrecht's admission that it paid $8 million in bribes for that project.

Following his

meeting with prosecutors, Garcia told reporters that he has never

requested nor accepted a bribe.

However,

Odebrecht's use of offshore companies and cash payments has created

challenges for prosecutors.

A binational

agreement has allowed Peruvian prosecutors to interview Odebrecht

directors within the framework of their cooperation with the

Brazilian court.

He believes that

this reflects the degree to which corruption has penetrated the

country's police and court system, a problem that he says has been

exacerbated in recent decades by the growing influence of money from

illicit activities such as cocaine production and illegal gold

mining.

IDL Reporteros published a transcript of Peruvian prosecutors' interrogation of Marcelo Odebrecht, the company's chief executive, which took place on May 15 in Curritiba, Brazil.

In it, Odebrecht claimed that in addition to donating $3 million to Humala's campaign, the company also donated money to the 2011 presidential campaign of Keiko Fujimori, whose party now holds a majority in Peru's Congress.

He added that it also probably aided the 2011 presidential campaign of current Vice President Mercedes Araoz, but that Barata, the company's director in Peru, would know for sure.

Araoz, who Alan Garcia selected to be his party's candidate but who resigned after two months of campaigning, says that she had nothing to do with her campaign's finances.

Fujimori has denied

receiving any funds from Odebrecht.

Brazilian

authorities subsequently

agreed to Barata's request to give

no further declarations to Peruvian prosecutors.

Alberto Fujimori resigned in 2000 after local media broadcasted videos of his intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, bribing opposition politicians and managers of Peruvian media.

Montesinos and

other Fujimori collaborators were arrested on corruption charges

following his resignation, but the Peruvian government is still

trying to

recover tens of millions of dollars

from bank accounts in Luxembourg and Switzerland linked to

Montesinos and the elder Fujimori.

Recent surveys indicate that Peruvians now consider corruption to be the country's biggest problem, after years in which crime was their top concern.

Whether or not that public sentiment can ensure that justice is served remains to be seen...

|