|

|

|

April 11, 2012 from CNET Website

wants to create the world's

first Internet provider designed to be surveillance-resistant.

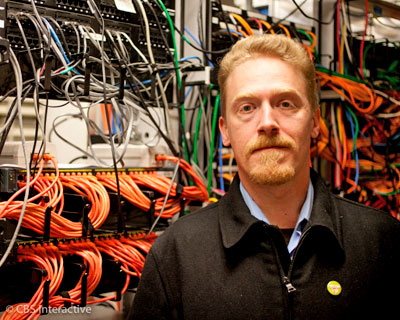

Nicholas Merrill is planning to revolutionize online privacy with a concept as simple as it is ingenious:

Merrill, 39, who previously ran a New York-based

Internet provider, told CNET that he's raising funds to launch a national

"non-profit telecommunications provider dedicated to privacy, using

ubiquitous encryption" that will sell mobile phone service and, for as

little as $20 a month, Internet connectivity.

Leading providers including AT&T and Verizon handed billions of customer telephone records to the National Security Agency;

By contrast, Merrill says his ISP, to be run by a non-profit called the Calyx Institute with for-profit subsidiaries, will put customers first

Merrill is in the unique position of being the first ISP exec to fight back against the Patriot Act's expanded police powers - and win.

Nick Merrill says that, "we will use all legal and technical means to resist having to hand over information, and aspire to be the partner in the telecommunications industry

that ACLU and EFF have always

needed but never had." In February 2004, the FBI sent Merrill a secret "national security letter" (not an actual court order signed by a judge) asking for confidential information about his customers and forbidding him from disclosing the letter's existence. He enlisted the ACLU to fight the gag order, and won.

A federal judge barred the FBI from invoking that portion of the law, ruling it was,

Merrill's identity was kept confidential for years as the litigation continued.

In 2007, the Washington Post published his anonymous op-ed which said:

He wasn't able to

discuss his case publicly

until 2010.

A 1994 federal law called the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) was highly controversial when it was enacted because it required telecommunications carriers to configure their networks for easy wiretappability by the FBI.

But even CALEA says that ISPs,

Translation:

Merrill has formed an advisory board with members including,

The next step for Merrill is to raise about $2 million and then, if all goes well, launch the service later this year. Right now Calyx is largely self-funded.

Thanks to a travel grant from the Ford Foundation, Merrill is heading to the San Francisco Bay Area later this month to meet with venture capitalists and individual angel investors.

While the intimacy of the relationship between Washington and telecommunications companies varies over time, it's existed in one form or another for decades.

In his 2006 book titled "State of War," New York Times reporter James Risen wrote:

Louis Tordella, the longest-serving deputy director of the NSA, acknowledged overseeing a project to intercept telegrams in the 1970s.

Called Project Shamrock, it relied on the major telegraph companies including Western Union secretly turning over copies of all messages sent to or from the United States.

Like the eavesdropping system that President George W. Bush secretly authorized, Project Shamrock had a "watch list" of people whose conversations would be identified and plucked out of the ether by NSA computers.

It was initially intended to be used for foreign intelligence purposes, but at its peak, 600 American citizens appeared on the list, including,

Nick Merrill says that, "if we were given any orders that were questionable,

we wouldn't hesitate to

challenge them in court." Even if Calyx encrypts everything, the surveillance arms of the FBI and the bureau's lesser-known counterparts will still have other legal means to eavesdrop on Americans, of course.

Police can

remotely install spyware on a

suspect's computer. Or

install keyloggers by breaking into a home or office.

Or, as the Secret Service outlined at last year's RSA conference, they can

try to guess passwords and conduct physical surveillance.

Last year, CNET was the first to report that the FBI warned Congress about what it dubbed the "Going Dark" problem, meaning when police are thwarted in conducting court-authorized eavesdropping because Internet companies aren't required to build in back doors in advance, or because the technology doesn't permit it.

FBI general counsel Valerie Caproni said

at the time that agents armed with wiretap orders need to be able to conduct

surveillance of "Web-based e-mail, social networking sites, and peer-to-peer

communications technology."

This article sparked a lengthy Reddit thread, complete with repeated suggestions that Nick Merrill should turn to Kickstarter to raise money.

Merrill told me this morning that Kickstarter,

But he has set up a contribution page, with a $1 million target, on IndieGogo.com, a self-described crowdfunding platform.

If he makes the $1 million target, IndieGogo

takes a smaller percentage. Internet privacy aficionados, what say you?

|