|

from RadarOnLine Website

Over the years, John Young claims to have exposed

276 British

MI6 agents, 400 secret Japanese intelligence officers, and 2,619 CIA sources

Click here to see John Young's

most controversial Cryptome posts

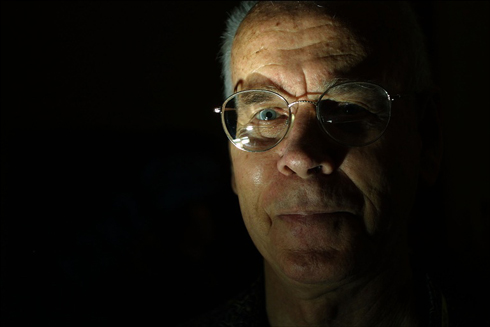

John L. Young asks that question a lot. When he poses it to me, leveling his intense, glassy blue eyes at mine across a barroom table on a muggy evening in late May, it is less a direct attack on my credibility than a cruel epistemological riddle.

Over the previous week, I had exchanged e-mails and spoken on the telephone with Young, a 71-year-old architect, spy buff, and proprietor of a strange and engrossing website called Cryptome, to set up an interview.

In doing so, I supplied him with certain data: my name [John Cook], occupation [reporter], employer [Radar magazine], location [216 E. 45th St.], e-mail address [redacted], telephone number [redacted]. Young craves data. He covets it, collects it, triangulates it, and uploads it to Cryptome - an online repository of forbidden information - where it collides with more data, gig after gig sloshing around in chaotic digital clouds.

There are high-resolution satellite photos of

President Bush's Crawford

ranch, technical documents detailing how the National Security Agency

spies

on computer traffic, even the home addresses and telephone numbers of

government officials, including former Director of National Intelligence

John Negroponte.

Before it is loosed on the Internet, scrubbed, cross-referenced, and interrogated by the hive mind for inconsistencies and cracks, it can be used to deceive. People lie. Misinformation is everywhere. People will use you; they will try to get you to believe things that aren't true in order to advance their own agendas.

It is, as Young likes to say, "standard tradecraft."

I could hand him a business card, show him a magazine, look him firmly and earnestly in the eye, and swear up and down that I am who I say I am.

There is no way out of this for John Young. He has a very good reason to suspect me, but he has good reasons to suspect everyone. Inquisitive reporters could have ulterior motives. Even the most casual of social interactions could be an attempt to shake him down for information.

Every

smiling stranger could be a Trojan horse; each friendly e-mail the beginning

of a sting. It must be exhausting.

Much of the material Young collects is stultifyingly dull - "RFC Keyed-Hash Message Authentication Code" will take the reader to an announcement in the Federal Register concerning a "mechanism for message authentication using cryptographic hash functions and shared secret keys" from the National Institute of Standards and Technology, for instance - but some of it is dangerous and even breathtaking.

WHO'S LOOKING OUT? Bill O'Reilly's home in Manhasset, NY, published on Cryptome last year

Hours after the FBI announced charges in June against four men for plotting to blow up jet-fuel tanks at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, Cryptome ran photos of the airport tank farms, pointing out the exact route of a jet-fuel pipeline buried beneath nearby residential neighborhoods. He regularly publishes satellite photos of the homes of intelligence officials, including CIA Director Michael Hayden's Washington, D.C., residence.

He has exposed

the names of what he claims are 276 British agents covertly working for MI6,

the names of 400 secret Japanese intelligence agents, and the names and home

addresses of what he claims are 2,619 CIA sources.

And the spies don't like it. After he posted the MI6 list in 1999, the British government reportedly asked his Internet service provider at the time to shut the site down. The company refused, but in May of this year, his hosting service suddenly, without explanation, announced that it would no longer have anything to do with the site. (Young promptly relocated to another service.)

He says he has received three visits to his home from the FBI, including one from a pair of agents with the Joint Terrorism Task Force.

Young's enemies have tried to shut the site down with

denial-of-service attacks. Officials at the National Security Agency read

his site with interest, and everyone wants to know where he gets his

information.

He doesn't understand why Radar is so interested in Cryptome.

He watches me, gauging my reaction. He thinks there's a story here, but it's not about him. It's about something else entirely. "People eat your stuff up," he says.

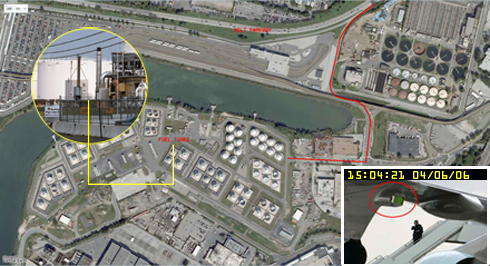

Young published these shots of JFK's jet-fuel tanks hours after a terrorist plot to blow them up was unraveled.

At right is a close-up

shot of Air Force One's anti-missile countermeasures

John Young doesn't look his age.

He "is fit and spry, and, with his coat, tie, and "close-cropped gray hair, the picture of upper-middle-class propriety.

Though he lives on Manhattan's Upper West Side, he wouldn't for a moment look out of place standing on a train platform in a Connecticut suburb with a briefcase in one hand and a Wall Street Journal in the other.

He is soft-spoken, polite, and capable of delivering vicious insults in a measured, calm voice with just the hint of a twinkle in his eye. He has a wicked sense of humor and an impish smile that he flashes like a switchblade. He likes to fuck with people.

Young cheerfully agreed to meet me in the bar of New York's Princeton Club, where his wife is a member, last spring. It wasn't until halfway into our two-hour conversation, during which Young was cryptic and reluctant to divulge anything but the most basic personal details, that I realized that it wasn't an interview.

It was an

operation.

He didn't tell me where, exactly.

He attended Rice University in Houston and did a stint in the Army Corps of Engineers before moving in 1967, at age 32, with a wife and four children in tow, to New York to pursue a graduate degree in architecture at Columbia University.

He studied there under James Marston Fitch, considered the father of the historic preservation movement.

In 1968, Young participated in the week-long seizure of Avery Hall, which housed the architecture school, during Columbia's student strike. He wasn't particularly radical, and says he joined in the protest "mainly because it seemed much more interesting than going to school."

But the strike, and the intellectual climate surrounding it, ignited something in him.

Young and his fellow Avery Hall activists founded Urban Deadline, an activist group-cum-architecture practice that sought, improbably, to change the world through design.

Throughout the early 1970s, Urban Deadline donated services to the poor, built storefront schools for high school dropouts, and scraped by on whatever paid contracts it could land.

Young, who was a few years older than his colleagues, reluctantly took on a leadership role despite the group's nominally egalitarian structure. Everyone wrote out their own paychecks at the end of each week. Young's first wife died of cancer either shortly before or shortly after his arrival at Columbia (memories of his former classmates differ, and Young wouldn't say), leaving him to raise their children on his own.

But, according to his fellow Urban Deadliners, he was single-mindedly devoted to the group and its radical goals.

He delighted in his own political obstinacy, and in poking his finger in the eye of whatever establishment figures were within reach.

When Columbia offered him a teaching position, he argued with the dean that he shouldn't receive any payment since he had no prior teaching experience.

Young once took out a series of ads in the small type along the bottom of the front page of the New York Times attacking I.M. Pei:

When he was invited to say a few words at an opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he told the audience of patrons,

Over the years, financial necessity caused Young's classmates to peel off and start their own practices, and Urban Deadline effectively dissolved in the late 1970s.

Young happened across the group when he first got online.

The cypher-punks concerned themselves with the policy implications of encryption technology, which at the time was a hotly debated topic. For the first time in the history of the electronic age, private citizens had access to powerful encryption software that allowed them to communicate with one another without government agencies having the option of listening in.

The NSA, which exists for no other purpose than to listen in, objected, and a series of protracted legal battles ensued between the federal government and privacy activists.

Philip Zimmermann, a cypher-punk

and the creator of the Pretty Good Privacy e-mail encryption software, was

investigated by the federal government in 1993 for making his software

available online, on the grounds that doing so constituted the criminal

unlicensed export of a weapon (charges were never filed).

Within months, he started to see daily visits from NSA computers. He'd gotten their attention. The site quickly shed its focus on cryptography, becoming a catch basin for random bits of information - data - about national security and government secrecy.

Young and his wife, Deborah Natsios, who helps him run Cryptome, assembled it all in one permanent archive, where readers can fall through the rabbit hole for hours, scanning presidential motorcade security procedures, reading declassified CIA case files, and viewing enhanced photos of that mysterious bulge in the back of President Bush's suit jacket caught on camera during the 2004 debates.

Young has posted 41,000 files so far and averages roughly 50,000 visitors per day.

Young reads the Federal Register every day, files FOIA requests, electronically clips news coverage of the intelligence world, and tracks down court documents.

He once paid a court reporter $9,000 for the complete transcripts of the New York trial of Osama bin Laden and 21 others for the Kenya and Tanzania embassy bombings. (He sells a DVD archive of everything on Cryptome for $25 apiece and sells ads on the site; aside from that, Young covers Cryptome's costs himself.)

The wild stuff: In July of 2000, a disgruntled former agent of the Public Security Intelligence Agency, Japan's version of the CIA, leaked Young a list of more than 400 PSIA operatives, which Young promptly published.

The Japanese government complained about the list to the FBI, and two agents called Young at his home to ask him to take it down.

Young refused, and published the names of the agents who called him. Three years later, two agents with the FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Force dropped in on Young unannounced.

They asked him to stop posting detailed aerial and street-level photos of nuclear installations, and to pass along any information he received that might help them unravel terrorist plots.

Young refused to take down the offending images, and told the agents that if he came across any information about terrorist threats, they could read about it on the site. After they left, he published the names of his visitors on Cryptome.

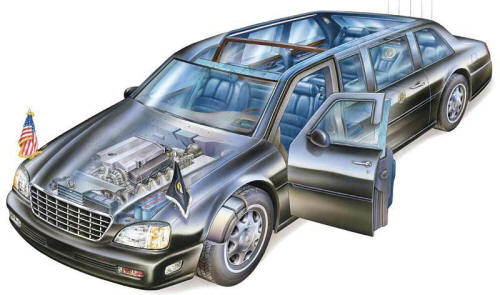

EXPLODED VIEW On the eve of Bush's second inaugural, Young published a "survey of presidential protection," including this illustration of the presidential Cadillac swiped from popularmechanics.com

Those sites removed the list at the request of the British government, but Young grabbed it before it went offline.

Since then he's added two more batches of names.

Earnest is also the chairman of the board of directors of the Association for Intelligence Officers, a group of retired spies, military intelligence officers, and even some journalists who cover intelligence, whose membership list - complete with addresses - Young published in 2000.

Even Young's admirers admit he goes over the line.

To Young, complaints about agents' safety is pure tradecraft. You can't argue with spies, because everything they say is a lie. Former covert operatives have told him as much, he says.

Young took this photo at Site R, the Pennsylvania mountain bunker

that reportedly served as Dick Cheney's "undisclosed

location" after September 11

For 90 minutes, through one and a half salted margaritas, John Young has been eyeballing me, speaking softly, fidgeting with the digital recorder I've placed in front of him.

He's heard all the questions I am asking

before, and he answers them carefully and pleasantly. Then he tells me why

he's here.

Haden-Guest has a

habit of calling magazine editors out of the blue from Chad or Syria with a

great story. He is a contributor to Radar and a personal friend of Radar's

editor in chief.

This was all in the strictest of confidence, Young says:

Afterward, Haden-Guest wrote a brief, laudatory article about Young

for a British newspaper. Roughly one year prior to my interview with Young,

Haden-Guest called Young again and proposed doing a more involved story on

him for Radar. They met at Haden-Guest's New York apartment for three hours,

Young says, and Haden-Guest tape-recorded the conversation. Young never

heard from him again.

And he

thinks I have something to do with it.

So he showed up to ping me.

Young believes that Haden-Guest and I are both working on stories about him.

But for MI6, not Radar.

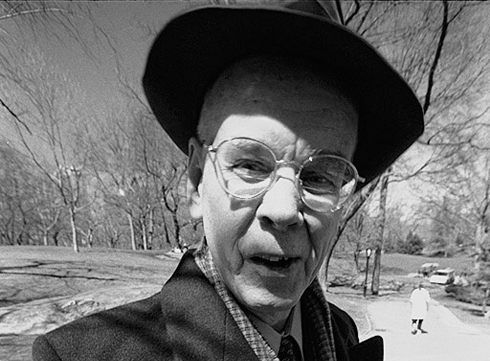

MASTER SPY?

Anthony Haden-Guest

I glance around at the tables next to us, concerned that someone might overhear our conversation. I don't know if it's because I don't want them to hear the paranoid rantings of a lunatic, or because I don't want them to hear the "truth" about Anthony Haden-Guest.

It is a simple and harmless set of facts: Radar killed Haden-Guest's story and handed it to me. That's not evidence of espionage. And so what if he bragged that people think he's a spy? Haden-Guest has been regaling acquaintances with fantastical-seeming tales for decades.

Why, if he really were an agent, would he volunteer - to John Young, of all people - that he's suspected of being an agent?

What seems like a reporter's effort to butter up a subject by appealing to his interest is also a tactic used by agents to inoculate themselves against being uncovered. It muddies the waters.

And why wouldn't MI6 send someone to ping the man who'd ousted 276 of

their agents, to see what clues he may inadvertently give up about his

sources? And who better than a reporter?

There

was the strange story in the British edition of Esquire about the Middle

East intelligence-gathering exploits of his friend "CK," who is "a

mercenary, if you like, one of the rare agents on the ground in this

high-tech epoch." But in the end, this was still the man who once appeared

on a panel discussion with Randy Jones of the Village People.

We see headlines now and again. We know - and quickly forget - that the CIA tailed Fox News Channel's Brit Hume, then a reporter for the late muckraking columnist Jack Anderson, in the 1970s.

That it kidnapped German citizen Khaled el-Masri in Macedonia, shoved a tranquilizer suppository up his ass, chained him to the floor of a plane, and flew him to an Afghan secret prison in 2004. That the NSA is capable of listening in on any communication, anywhere. This is what they do. It's not so crazy to imagine they'd check in on someone like Young. It's standard.

You just have to know what to look for.

A relatively well-known media figure has all but told him that he's an agent, using a magazine as cover, and for some reason - Affection? Vanity? - Young hasn't posted a word of it to Cryptome.

He rants about the betrayal, then drops it, and tells me that he's willing to put me in touch with good sources for national security stories. Then he insults me. A half-hour ago he said he found Radar "delightful"; now he finds it insipid.

I point out to him that he's alternating between affability and belligerence, and he bangs on the table with glee, delighted that I noticed.

Young points out how easy it was for me to set up the interview, how accessible he made himself to me.

Am I being recruited?

My mission, should I choose to accept it: Find out what happened to Haden-Guest's story, and write about Haden-Guest's alleged MI6 connection in Radar.

If I don't, Young will write about it on Cryptome.

John Young

In person and online, Young casts himself as an outsider and misanthrope. There is some truth to this portrayal.

At the same time, he has done architectural work for some of the most powerful members of the political establishment that he has sworn to attack.

He has worked for the Council on Foreign Relations, the bête noire of the conspiracy set. He was, for six years in the 1980s, the consulting architect to the Pierre, a Fifth Avenue apartment hotel that has been home to Sumner Redstone and Mohamed Al Fayed.

His résumé cites work on developer Kirk Kerkorian's residence there.

During the renovation of Grand Central Terminal in the 1990s, he was hired to document the existing structure and spent days in the rafters above the vaulted Main Concourse, meticulously measuring beams. He is respected enough in his field to have been selected, in 1998, for the nominating committee for the Chrysler Award for Innovation in Design.

He nominated James Bell, a Washington man who was convicted in 2001 of stalking U.S. Treasury agents, for Bell's online essay,

If it's incongruous to imagine a paranoid, spy-hating anarchist going over blueprints with Mrs. Kerkorian, consider the preposterous, cosmically incomprehensible case of John Young's late father-in-law.

Young has been married at least three times; in 1993 he met his current wife, Deborah Natsios, the daughter of Nicholas Natsios, a career CIA officer who served in Vietnam, Iran, and elsewhere.

Young disclosed the fact on Cryptome in 2000:

When Young published the membership list of the Association for Intelligence Officers four months later, Nicholas Natsios's name and home address were on it.

Natsios died in 2004.

When I called his daughter Christine Natsios - Young's sister-in-law - to ask her what she thought of Cryptome, she replied,

Deborah Natsios's cousin is Andrew Natsios, currently the State Department's

special envoy to Sudan and formerly the administrator of the Agency for

International Development, appointed by George W. Bush. The CIA is commonly

thought to use USAID positions as cover overseas. Disclosing the

relationship on Cryptome, Young described him as a "low-paid hardworking

honest guy mired in a hopelessly venal fat-cat system."

He describes it as a public education project.

But for every hard data point he offers, there's the ever-present admonishment that secrecy corrupts everything.

It's like a nihilist art project: Provide your readers with

more than 40,000 files of data the government doesn't want you to have, data

that exposes the lies of the powerful, and then remind them that you can

never, ever know for sure who is lying.

The next day he wrote Haden-Guest an e-mail, which he also posted on Cryptome:

He didn't return further e-mails or phone calls.

Several days later, when Young started getting calls and e-mails from friends alerting him to my inquiries for this story, he posted this:

Young continued to post his correspondence about me with various friends and relatives I had contacted for this story. His daughter Anina Young, who operates an online clothing store in New York, asked me to put my questions in an e-mail; she never replied, but the e-mail showed up on Cryptome two days later.

Young called Radar a "vile magazine," accused me of "hounding" his family, and advised his associates that I would tell them a "mixture of truth and lies" in order to "seduce and betray" them.

When I called Haden-Guest to let him know what Young had been saying about him, he replied that he had never told Young that he was commonly suspected of being a spy, or that he worked for British intelligence, and insisted that he had never done a thing for British intelligence.

He said he wished he had let Young know about the disposition of his story, but had been preoccupied with moving back to London from New York City.

He was concerned that someone like Young would spread a false rumor that he was MI6.

A few days later, Haden-Guest sent Radar an e-mail elaborating on Young's claims, chalking them up in part to anger over the fact that the original story never appeared:

Toward the end of my conversation with Young, he returned to the question that plagues him:

Then he said he had to wake up early in the morning.

On our way out, he invited me upstairs to have a look at the Princeton Club's second-floor lounge area.

He had mentioned earlier in our

conversation that the club had gone downhill, and how pleasant the sitting

area once was. I let him lead the way. His insults were still reverberating

in my head; I was reeling from the notion that I was involved, unwittingly,

tangentially, in an operation to spy on this 71-year-old man. He had been

berating me not 20 minutes earlier, and here he was, utterly charming,

leading me up the wide staircase into an empty room filled with stuffed

chairs and reading lamps.

We walked into the lounge area. He stopped and let me walk a few feet ahead.

The most controversial posts from John Young's Cryptome

BUNKER BUSTER With his website, Cryptome, John Young aims to publish forbidden information,

including these photos of Dick Cheney's mountain

bunker

John L. Young, the obsessive genius behind Cryptome, has been infuriating governments worldwide for years by assembling a library of sensitive, often classified, information about intelligence-gathering and national security.

Below is a list of some of his more illuminating chestnuts:

|