|

by Roy Peachey

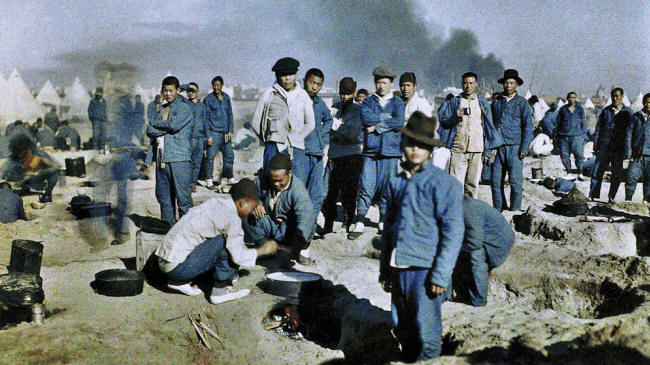

in an early color photograph. Some 140,000 laborers were recruited by Britain and France and another 200,000 by Russia ©Paul Castelnau / Galerie Bilderwelt

Getty

Images

A third of a million Chinese laborers helped the Allies defeat the Kaiser, but their huge unsung contribution ended in betrayal...

While studying in the School of Oriental and African Studies library a few years ago, I stumbled across Guoqi Xu's China and the Great War and was taken aback by the book's title.

I had a degree in modern history from Oxford and had taught history in secondary schools for several years, and yet I knew nothing about China's involvement in the First World War.

I abandoned the essay I was supposed to be writing, borrowed the book, and set off on a journey of historical discovery.

Hunting down every bit of information I could find on the topic, I interrupted family holidays to visit Chinese cemeteries in northern France and eventually wrote a novel about what I had discovered.

The potential impact of

idly browsing in a library should never be underestimated.

The narrative with which we are most familiar tends to focus on European battles and European ambitions.

But if we ignore the war's Asian dimension, we inevitably develop an inadequate understanding of 20th-century history.

What happened during the

war and afterwards at Versailles defined the nature of Sino-Japanese

relations for the next hundred years, provoked a political and

cultural revolution in China, and led indirectly to the rise of the

Chinese Communist Party.

By the time the Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion were over, more than a dozen European countries had acquired territorial interests in China, annexing territories such as Hong Kong and Taiwan and establishing enclaves, known as concessions, in west-coast ports including Shanghai and Tianjin.

My students now learn about the Opium Wars, but the first I heard about them was when I saw an exhibition in a Hong Kong museum as an adult:

'The story of China and the Great War is not an incidental tale, a mere coda to a greater European symphony. The Chinese experience provides a salutary reminder

that the Great

War was indeed a world war'...

Having gained a foothold

in the province of Shandong, it quickly developed the city into what

it hoped would be a model colony, the remains of which can be seen

to this day in the architecture of several churches, the impressive

façade of the former governor's residence and, above all, in the

world-renowned Tsingtao Brewery.

However, it also faced the possibility of being over-run by warring imperial powers.

Hoping to keep the conflict at arm's length, the Chinese government immediately announced its neutrality. But neutrality proved to be a vain hope...

Japan, seeing an opportunity to strengthen its extra-territorial interests, laid siege to Qingdao with British help and by November 1914 had driven the Germans out and taken their place, quickly extending their reach into the whole province.

The British were delighted by this early Allied victory:

They may have been quite

happy to see the Germans dispatched from Qingdao, but their

replacement by Japanese troops who were clearly keen to further

extend Japan's sphere of influence was hardly the outcome they had

been seeking.

Determined to regain full

territorial integrity while being acutely aware of domestic

instability, the Chinese government did all it could to persuade the

Allies to return Qingdao and the rest of Shandong to Chinese

control, which meant that it had no alternative but to support the

Allied war effort.

When this offer was rejected by Britain, one of the leading Chinese politicians of the time, Liang Shiyi, came up with a new idea:

By offering laborers to

the Allies, the Chinese hoped to win a seat at the post-war peace

conference and so ensure that the territory that had been wrested

from them would be swiftly returned.

Desperate for additional manpower in France, the British turned first to their own colonies and dominions for troops and laborers, though this approach proved to be problematic.

Not only was it a struggle to recruit enough men but the policy also created imperial unease on a grand scale.

The Boer newspaper, Ons Land, summarized the concern most explicitly when it reported that,

This can only be

detrimental to the image of Western culture and of the whites.

With British trade unions also voicing their concerns, the British government held back from sanctioning the use of Chinese labor until France forced its hand.

When the French government decided in late 1915 to start recruiting Chinese laborers, pressure built on the British to do likewise.

After a slow start, the recruitment process quickly gathered momentum. Eventually some 140,000 laborers were recruited by Britain and France, while Russia hired another 200,000 men.

By the time China

declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary in August 1917, many

thousands of laborers had already travelled to Europe and many had

died.

From there they were

transported via Canada to Britain and then across the Channel to

France, arriving at the headquarters of the Chinese Labor Corps

(or CLC) at Noyelles-sur-Mer at the mouth of the Somme.

Wood, who travelled with the Chinese Labor Corps from Weihaiwai on the SS Coconada in September 1917, kept a diary during the journey which reveals a great deal about the daily experience of the laborers and a great deal more about the attitudes of the men who were responsible for keeping them in their place.

The very first entry in the diary, for example, tells us that,

What sort of steps are revealed in a later entry, which reveals that,

Another diary that was later published, with the revealing title of With the Chinks, more explicitly reveals the casual racism the Chinese laborers were subjected to.

The diary's author, Second Lieutenant Daryl Klein, admitted that,

However, even though he now distanced himself from that view, Klein clung onto a hardly less flattering caricature of the men he was responsible for, writing that,

Making the sea journey to France was a perilous business.

According to Guoqi Xu, approximately 700 Chinese laborers lost their lives as a result of German submarine attacks before they reached their destination.

However, what they found when they eventually arrived at Noyelles was a remarkable base camp.

The headquarters of the CLC developed very quickly from a holding camp to a major centre that provided a temporary home from home for the Chinese laborers in northern France. One of the most impressive aspects of the base was its hospital, which rivaled any hospital in China at the time.

This is how one of the British officers proudly describes it to a Chinese translator, with only a little exaggeration, in my novel:

Though the contracts for Chinese laborers explicitly stated that laborers were,

...the reality was that many Chinese workers ended up working at or very close to the front line.

Casualty rates were therefore much higher than many of the laborers had been led to believe when they were recruited.

The doctors at Noyelles

were required to treat bullet and shell wounds as well as a wide

range of industrial injuries, to say nothing of the diseases,

chiefly trachoma, that many laborers brought with them from China.

That meant that Chinese laborers were soon given a wide range of back-breaking tasks to do, including digging trenches, repairing roads, building railway lines, and manufacturing tanks and ammunition.

They also did what was

euphemistically known as battlefield clearance. This was perhaps the

deadliest task of all, as a moving visit to the Chinese cemetery at

Noyelles brought home to me.

were killed while clearing bodies, barbed wire and the detritus of war from the killing fields of

northern France

and Belgium'

How unlucky can you get? Quite a lot more unlucky, it transpired...

The next gravestone marked the last resting place of Teng Hsi T'ien who died on November 12 and the one after that the grave of Pan Chung Shan who died on November 13.

Walking down one row

after another, I saw the graves of hundreds of men who died after

Armistice Day. In fact, over half of the 841 men buried at Noyelles

died after November 11, 1918, the last death being recorded

on March 23, 1920.

"Battlefield clearance"

is such an innocuous phrase and yet the reality was horrifying.

Sometimes the ground had been marked by retreating Axis troops, a helmet hanging from a wooden stake, or a piece of wood with the letter E burnt into it, signaling the site of an English grave.

However, as often as not, these markers were non-existent, having been blown to pieces by heavy shelling or never having existed in the first place.

In those situations the laborers had to rely on other indications of decay:

Marking smaller burial sites with yellow flags and larger ones with blue flags, the laborers began to carve out the war cemeteries with which we are so familiar today.

What we see is order and beauty, fitting tributes to the war dead in the north European countryside: what the laborers faced was a blasted landscape, a confusion of body parts, and unexploded ordnance.

Here is how I describe their work in Between Darkness and Light:

The dates of World War One may be engraved on the British collective memory but the Chinese experience of war reminds us that limiting the war to the years 1914-1918 is very misleading.

For the Chinese, the war started in 1914, but only ended when the last of their laborers was killed in 1920 or even later, if we consider the catastrophic situation faced by those laborers who were dispatched to Russia only to be caught up in the revolution and subsequent civil war.

the Chinese cemetery at Noyelles-sur-Mer

(FELIX

POTUIT)

They were quickly forgotten, their presence in Europe an embarrassment and their contribution to the war effort largely unacknowledged.

When the war ended, the British and French kept as many laborers as they required for battlefield clearance and repatriated the others as quickly as was practically possible.

A few laborers stayed on

in France and elsewhere, marrying local women or continuing to work

in the docks or in other places where they had made themselves

particularly useful.

As Lord Bourne has pointed out:

That is why an alliance of Chinese groups in the UK is currently working towards the creation of the first permanent memorial to the Chinese Labour Corps in Britain.

They have chosen the name Ensuring We Remember for their campaign and at times bringing such memories to the surface must have seemed like a forlorn hope.

There are, though, signs

that the First World War's Asian dimension is finally being

recognized in the West.

Having maneuvered themselves into a position where they believed they would be able to influence the course of events and win back the territory that Japan had seized from them, the Chinese government was thwarted once more when negotiations got under way.

In fact, the writing was on the wall even before the conference got going.

Though Japan was given five seats at the conference, China was granted only two. Having contributed troops to the war effort, the Japanese always held the upper hand in the post-war negotiations, especially as they had frequent support from the American delegation, led by Woodrow Wilson himself, which was desperate to ensure that Japan signed up to the League of Nations.

Handing Qingdao and the

surrounding regions back to China would almost certainly have

scuppered that ambition. The Chinese delegation, led by Lu

Zhengxiang, was on the back foot from the very start of the

conference.

When it became apparent that the Allies planned to honor these agreements, even though they had been made under considerable duress, thousands of students poured onto the streets of Beijing in protest.

May 4, the date of those initial demonstrations, became the most resonant date in modern Chinese history, the protests spawning a new political, social and cultural movement.

If you visit Qingdao today, you will find the waterfront dominated by a huge red memorial to the May Fourth Movement. But the humiliation at Versailles did not simply leave a legacy of colorful public sculptures.

The May Fourth

Movement transformed Chinese social and political affairs and

led indirectly to the creation of the Chinese Communist Party

itself. China may have been an afterthought to the so-called Big

Four at Versailles, but the events that were set in train at the

conference came back to haunt the Allied nations later in the

century.

However, as Lu Zhengxiang explained in his memoirs,

June 28, 2019 is not just the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles:

The war was now

officially over, but for the Chinese laborers and the government

that had sent them to France the battle for recognition and equality

of esteem had only just begun.

|