|

by Max Roser

March 05,

2021

from

OurWorldInData Website

Who is

Considered Poor

in a Rich

Country?

And what does

this Mean for

our

Understanding of Global Poverty?

Our World in

Data presents

the data and

research to make progress

against the

world's largest problems.

This post draws on data and research

discussed in our

entries on

Income

Inequality, Global Extreme Poverty

and Economic

Growth...

Abstract:

The

extremely low poverty line that the UN relies on has the

advantage that it draws the attention to the very

poorest people in the world.

It

has the disadvantage that it ignores what is happening

to the incomes of the 90% of the world population who

live above the extreme poverty threshold.

The global poverty line that the UN relies on is based

on the national poverty lines in the world's poorest

countries.

In

this article I ask what global poverty looks like if we

rely on the notions of poverty that are common in the

world's rich countries like Denmark, the US, or

Germany.

Based on the evidence I ask what our aspirations for the

future of global poverty reduction might be.

In every country of the world there are people living in poverty.

Even in the world's richest countries the poorest people often live

in poor housing and struggle to afford basic goods and services like

heating, transport, and healthy food for themselves and their

family.

Those who are in monetary poverty also have much poorer living

conditions more broadly.

Even in a rich and relatively equal country

like Denmark middle-aged men who are among the poorest 20% of the

population die on average 9 years earlier than those among the

richest 20%. 1

In Denmark a person who

lives on less than $30 per day is considered poor and it is the

declared goal of the country to reduce poverty relative to this

threshold. 2

Countries

that are much poorer than Denmark also have the goal to

reduce poverty.

The United Nations declared the objective of

ending 'extreme poverty'

to be the number 1 goal of the global Sustainable

Development Goals.

According to the UN a person is considered to live in

extreme poverty when he or she is living on less than $1.90

per day, this is called the International Poverty Line.

According

to the latest global statistics about one in ten

people live in extreme poverty globally.

3

If we know

that poverty is a large problem even in high income

countries like Denmark where the poverty line is set at

around $30 a day, why should we use an International Poverty

Line that is so extremely low to measure poverty globally?

It is the

reality of our extremely unequal world in which every

tenth person lives in extreme poverty that makes such an

extremely low poverty line necessary. Without having an

extremely low poverty line we would not be aware of the

fact that a large share of the world lives in such extreme

poverty.

The UN's

global poverty line is valuable because it draws attention

to the reality of extreme poverty in our world.

In a world

where the majority still lives on very low incomes it would

be wrong if the UN decided to measure global poverty solely

by a poverty line as high as the poverty line of Denmark.

It would

mean that the global statistics gloss over the extremely

large and important income differences among the poorest

billions in the world.

It would

mean that the difference between those who live on only $1

per day and those who have an income that is more than

20-times higher would be entirely disregarded. They would

all be considered poor, and the reality that some of them

are much poorer than others would be hidden.

Slightly

higher global poverty lines such as the poverty line of

$3.10 per day that Kate Raworth relies on in her 'Doughnut'

framework, or the poverty line of $7.40 per day that

anthropologist Jason Hickel uses in his work, or Bob Allen's

absolute poverty line based on minimal nutritional

requirements all have the same value.

4

These low

poverty lines allow us to understand the material living

conditions of the poorest people in the world and have been

successful in drawing attention to the terrible depths of

poverty experienced by a large share of the world's

population.

The only

way to achieve these goals is to rely on extremely low

poverty lines.

Indeed

there is an argument for using an even lower poverty line.

To

understand what is happening to the very poorest in

the world, we need to look even lower than $1.90. This is

because one of the biggest failures of development is that

over the last decades the incomes of

the very poorest people have not risen.

A big part

of the reason for why this issue doesn't get discussed

enough is that the International Poverty Line we rely on is

too high to see this fact.

Yet,

only measuring global poverty relative to such

extremely low poverty lines has its own large downside.

By focusing

on an income threshold that is lower than the incomes of 90%

of the global population we are ignoring what is happening

to the majority of the world's population. This matters.

The

majority of the world do not live in extreme poverty

anymore, but billions are nevertheless living in great

poverty still.

The obvious

solution to the problem that the majority of the world is

not considered by the International Poverty Line is to use

an additional poverty line. This is not a new idea.

One poverty

researcher who has made the argument for an additional

higher global poverty line based on the notions of poverty

in rich countries is Lant Pritchett you find it in his

short, yet widely-cited essay 'The case for a high

global poverty line' from eight years ago.

5

Defining

global poverty lines

The

definition of poverty differs between countries. Poorer

countries set much lower poverty lines than richer

countries.

6

This means

that if we were to simply rely on national poverty

definitions for a global measure of poverty we would end up

with a measurement framework in which the fact where

a person happens to live would determine whether they are

poor or not:

If we

would count as poor those who are defined nationally as

poor we would end up counting a person who lives on $20

per day as poor in a rich country, while at the same

time counting a person who lives on $2 as not-poor when

they happen to live in a very poor country.

One way out

of this problem is to set global poverty lines based on the

national definitions, but to apply them globally.

This is how

the UN decided to define the International Poverty Line.

In order to

ground this global poverty line on something more than the

views of global poverty researchers, it is set based on the

existing definitions of poverty adopted in countries around

the world at the national level, but to avoid the problem

outlined above they apply the national poverty lines

globally.

As we

explain

here in some detail, the $1.90 per day poverty line is

set to reflect the national poverty lines adopted in the

world's poorest countries.

7

Applying

this poverty line globally means that a person who lives on

less than $1.90 per day is considered extremely poor no

matter where they live.

In recent

years the World Bank has applied this same methodology to

countries in the middle-income bracket, those countries with

a GNI per capita between $1000 and $12,500.

Based on

the poverty lines in these countries they have set

additional global poverty lines at $3.20 and $5.50 per day,

which are now

directly

available via the World Bank statistics.

8

What I want

to do here is to see what a global poverty line would be if

we rely on the notion of poverty in rich countries countries like Denmark, the US, or Germany.

9

That is what Pritchett suggested eight years ago:

"Since

the origin of the [International Poverty Line] was just

to adopt as a global lower bound the poverty lines used

by the poorest countries, it symmetrically makes sense

to say that the global upper bound poverty line is based

on the poverty line used in rich countries."

The

definition of poverty is certainly not an easy ethical

question and thoughtful people disagree about it in ways

that have meaningful consequences for our understanding of

the world.

There are

also interesting proposals for hybrid poverty lines that

combine absolute and weakly-relative measures, see Ravallion

(2019) for a recent proposal.

10

And I would

also recommend Tony Atkinson's last book 'Measuring

Poverty around the World' for an excellent recent

overview of the topic.

The basics of global

poverty measurement

Throughout

this article and in global income and

expenditure data generally the

statisticians who produce these figures

are careful to make these numbers as

comparable as possible.

First,

many poorer people rely on subsistence

farming and do not have a monetary

income.

To take

this into account and make a fair

comparison of their living standards,

the statisticians that produce these

figures estimate the monetary value of

their home production and add it to

their income/expenditure.

Second,

price changes over time (inflation) and

price differences across countries are

both taken into account: all measures

are adjusted for differences in

purchasing power.

11

To this

end incomes and expenditures are

expressed in so-called international

dollars. This is a hypothetical

currency that results from the price

adjustments across time and place.

An

international dollar is defined as

having the same purchasing power as one

US-$ in the US.

This means no

matter where in the world a person is

living on int. $30, they can buy the

goods and services that cost $30 in the

US.

None of

these adjustments are ever going to be

perfect, but in a world where price

differences are large it is important to

attempt to account for these differences

as well as possible, and this is what

these adjustments do.

12

Throughout

this text I'm always adjusting incomes

for price changes over time and price

differences between countries in this

way. All dollar values discussed here

are presented in int. $; the UN does the

same for the $1.90 poverty line.

Sometimes

I leave out 'international' as it is

awkward to repeat it all the time; but

every time I mention any $ amount in

this text I'm referring to

international-$ and not US-$.

13

An additional higher poverty

line of $30 per day

Pritchett

made his proposal based on data and prices a decade ago and

so it is necessary to update his calculations.

But I want

to go beyond Pritchett's approach and additionally provide a

number of other relevant comparisons to inform our

understanding of who is considered poor in a rich country.

By

following this idea I find that a poverty of 30

international-$ per day corresponds to the notion of poverty

in a rich country. In the following section I consider a

long number of benchmarks that made me arrive at this

poverty line.

Here is the

short summary of these comparisons:

The range

of possible higher poverty lines based on richer countries

is wide, as the list of benchmarks suggests.

At the

lower end I believe that it might be as low as $25 per day,

and on the higher end it might be as high as $40 or $50 per

day.

Just as

someone who lives on less than $1.90 per day is defined as

extremely poor, a person who lives on less than $30

a day could be considered moderately poor.

A reality

check for any poverty line you might want to consider is to

ask yourself what you think about living on less than that

poverty line yourself. I lived on less than $30 per day

before and would consider myself poor if I'd fall back on

that income level again.

In the

following box you find the sources and calculations of the

benchmarks that led me to my $30 per poverty line proposal.

Who is considered poor in

rich countries? Poverty lines and other relevant benchmarks

Poverty lines in European countries

As

mentioned before most European

countries set their poverty line at

60% of the median income in the

country.

In his

original proposal Pritchett was

relying on this 60% of median

cut-off.

Calculating the poverty line for

European countries therefore means

that we look up their median income

and then multiply it by 0.6. This is

less straightforward than it might

first appear. The reason for that is

that there are many different income

concepts.

You

quickly realize that it is not easy

to define a person's income if you

ask yourself what your own income

is.

Do

you take government transfers

into account or not?

Do

you take your partner's income

into account and divide it by

two?

How do you take into account

that you have a child for which

you need to pay?

It is

possible to take these and many

other aspects into account and

arrive at useful statistics, but

various sensible ways of addressing

such questions lead to many

different income metrics.

As

such, in comparing different poverty

thresholds across countries we have

to take care to avoid mixing

different income concepts as much as

possible.

One

important difference is how incomes

are adjusted for the size of the

household: whether the total

household income is simply divided

by the number of people (including

children) 'per capita' income or

whether some adjustment is made to

account for the fact that larger

households, and particularly

households with children, face lower

costs per person known as 'equivalised'

income.

Whereas EU countries, like other

rich countries, use equivalent

income to measure poverty, the UN's

measurement of global poverty is

based on a global dataset of per

capita incomes.

This

dataset is called

PovcalNet, and it is this that

we must use in order to make

comparisons of poverty measures in

different countries according to the

same income concept.

In

this dataset we find the median

income for countries around the

world and we can take that median

income and then apply the logic on

which the European poverty lines are

based. In the extensive footnote

here you find more details and the

full calculations.

14

As

high-income European countries I'm

referring to those European

countries, which

according to the Eurostat statistics

had a higher income in 2019 than the

European average.

These

are the following countries:

Finland, Netherlands, Belgium,

Sweden, Germany, France,

Iceland, Switzerland, Norway,

Luxembourg, Denmark, Austria,

Ireland, and the UK.

These

are the poverty lines for daily

income in a number of high-income

European countries (based on 60% of

the median incomes from PovcalNet):

-

Sweden: $29.40 per day

-

Norway: $37.80 per day

-

Austria: $31 per day

-

UK: $25.04 per day

-

Switzerland: $35.82 per day

-

Germany: $28.35 per day

-

France: $27.28 per day

-

Luxembourg: $43.86 per day

-

Finland: $27.22 per day

-

Iceland: $31.64 per day

-

Ireland: $24.68 per day

-

Netherlands: $28.6 per day

-

Belgium: $26.92 per day

-

Denmark: $29.06 per day

The

span of poverty lines in these

countries ranges from $25 (for the

UK and Ireland) up to $38 (for

Norway).

In the small country of

Luxembourg the poverty line is

higher.

The

poverty line in the US

Unlike

European countries, the US does not

set the poverty line in a relative

way. Instead the US poverty line

dates back to the work of Mollie Orshansky, an economist working for

the Social Security Administration

in the early 1960s.

Since

then it has been of course revised

for price changes, but otherwise it

remained unchanged.

The US

poverty line is

very often criticized as being

too low. Those that criticize the US

poverty line in that way therefore

suggest that the severity of poverty

in the US is understated in the

statistics.

How

high is the poverty line in the US?

In 2020 the poverty threshold for a

single person under 65 was 35

international-$ per day.

15

Now

the problem with comparing this

poverty line with the global

statistics is again that the income

concept is different. The US

crucially relies on an equivalence

scale for adjusting the income

cutoff depending on the household

size.

An

alternative is to apply the same

concept that the Europeans are using

for their poverty line

determination. If the US would use

the 60% of median income definition

of poverty their poverty line would

be int. $32.8 per day.

16

Very

close to the one-person poverty line

based on Orshansky's work.

A

somewhat comparable poverty line

based on these two approaches

therefore falls into the range of

around $33 to $35 per day.

Within

the range of poverty lines in

European countries.

Survey results Below which income do

you consider a person poor?

The UN and

Pritchett rely on the existing poverty

lines in low-income and high-income

countries respectively to derive their

poverty lines. We can follow other

approaches too.

An obvious

one is to ask what people out there

believe:

Who is

considered poor in a high-income

country by people in high-income

countries?

For the

regular poverty report of the German

government, a survey is conducted that

asks Germans below which income level

they consider someone as poor.

The latest

data is from the year 2015.

17

The mean

answer given by the German population

for a cutoff below which a person is

considered poor was 947€ per month. In

international dollars per day this

corresponds to an income of

int. -$37.58.

18

Universal Basic Income

Universal Basic Income

(UBI) is a political idea that is

becoming rapidly more popular.

A

large UBI study in Germany called

'Mein Grundeinkommen' sets

this income at €1200. In

international-$ this corresponds to

an income of int. $48.19 per

day.

19

Social

security in Germany

Germany pays basic social care for

its citizens. This social security

payment is referred to as 'Hartz-IV'.

How

much a person receives depends on

the particular circumstances of the

individual, but we can look at the

average payment. In 2018 a single

person

received on average 783 Euro per

month.

That corresponds to

int. -$30.78 per day.

20

The

Roslings' suggest a cutoff of $32

per day

Anna

Rosling-Rönnlund, Ola Rosling and

Hans Rosling challenged the old

dichotomy between developed and

developing countries in their

bestselling book 'Factfulness'.

They argue that the old dichotomy

corresponds to a view of the world

that was accurate half a century ago

when a few countries were relatively

well-off, but most countries were

living in very

poor conditions.

Today, they say,

people around the world live on a

large spectrum. To reflect this

spectrum they proposed 4 income

levels.

The

first cut-off corresponds to the

international poverty line (rounded

to int. $2 per day). The next income

cutoff they set at $8 per day, the

following one at $16 and the highest

one at int. $32 per day.

Kahneman's and Deaton's study of

income and emotional well-being

Nobel

laureates Daniel Kahneman and

Angus

Deaton published a famous study on

the link between life satisfaction

and income.

2

The

authors find that higher incomes go

together with higher self-reported

life satisfaction, but for people's

self-reported emotional well-being

this is only true up to a certain

point:

the study finds that above

$75,000 further increases in

income do not correspond with

improvements in people's

emotional well-being a finding

that is often cited to argue

that additional economic growth

does not improve people's lives

in high-income countries.

22

Again, the

income concept is not the same as that

in PovcalNet, and so comparisons with

the global data are not directly

possible.

But we can

ask what the daily income at which

emotional well-being supposedly levels

off corresponds to: $75,000 per year are

int. $205 per day.

It is

certainly worth considering whether an

income up to which emotional well-being

increases could be taken as the basis

for a definition of poverty.

A US

company reacted to the research finding

of Kahneman and Deaton by using it to

set the minimum wage in their company:

everyone in that company

gets paid that salary.

For the

discussion of global poverty however it

might be considered as an even higher

poverty line, but for any practical

purpose in the world today the income

cutoff would be too high as only a very

small fraction of the world lives on

more than $75,000 per year.

How many

people in the world live in poverty?

We have

seen that 10% of the world live in extreme poverty

as defined by the UN. How large is the share of the world

that lives in moderate poverty?

The latest

global data tells us that 85% of the world

population live on less than $30 per day.

These are

6.5 billion people...!

Relying on

a higher poverty line of $45 per day you find that 92% live

in poverty and using a lower poverty line of $20 per day you

find that 78% live in poverty.

No matter which of these

poverty lines you might want to choose, at least

three-quarters of the world live in poverty.

All of this

data refers to pre-pandemic times...

The global

recession has certainly increased the share below any of

these cutoff points. As soon as the new data is available

you will find it on Our World in Data.

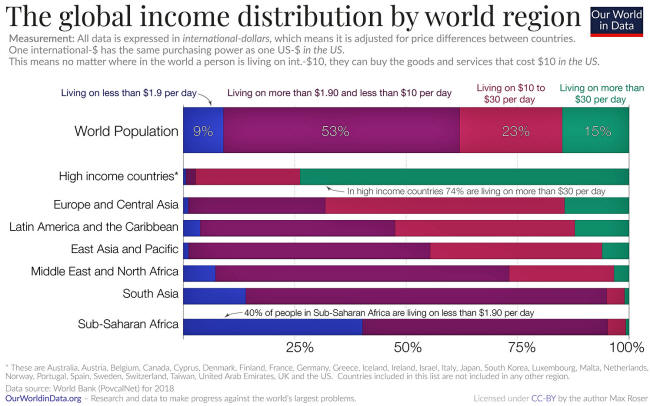

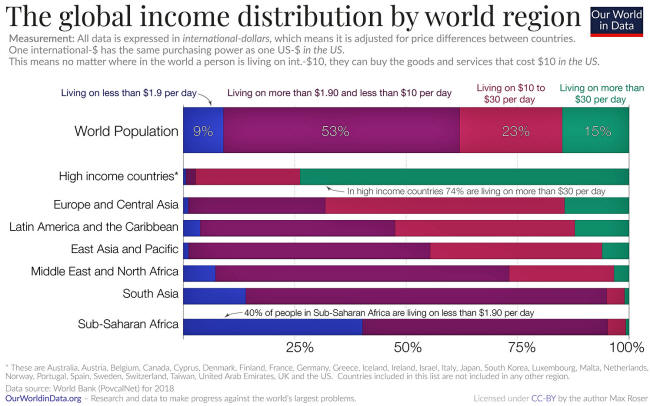

The chart

shows where in the world people are poor. If we would only

rely on the UN's extreme poverty line we would conclude that

barely anyone lives in poverty in high-income countries.

Relying on

higher poverty lines, this data here shows that even in

high-income countries there is a significant share of the

population that lives in poverty. No country, not even the

high-income countries, have eliminated poverty.

There are

no 'developed countries' there is work to do for all.

But just as

clear from this data is the fact that in many world regions

the large majority of people are very poor. In Sub-Saharan

Africa about 40% of the population lives on less than $1.90

per day as the chart shows.

In all

regions outside of high-income countries more than 85% of

all people live in moderate poverty.

Countries in

which the majority do not live in poverty have only left

poverty behind in recent history

Two

centuries ago the global income distribution was very

different.

Back then

almost everyone in the world was living in extreme

poverty. Those places in which few people live in moderate

poverty today only left poverty behind in the very recent

past.

Denmark is

one of those places. The reason why the majority of people

in Denmark is not living in poverty is that the economic

inequality is low and the average income high.

The fact

that the inequality is low you can see on the map. It shows

an inequality measure called the Gini coefficient (explained

here) which makes clear that Denmark is among the least

unequal countries in the world.

The reason

that the average income in Denmark is high is due to the

fact that average incomes have increased steadily for the

last two centuries, this long-term development is called

economic growth.

As the

historical data shows the average incomes in Denmark are

today more than 20-times higher than in the past.

You can add

any other country to this chart. By adding one of those

countries in which the majority lives in poverty like

Ethiopia you see just how large the differences in average

incomes are.

GDP per

capita is by far the most widely used measure of average

income and is yet another income concept from the two I

mentioned so far.

23

It is a

more comprehensive measure of incomes and crucially takes

into account government expenditures.

For these

and other reasons (mentioned in the long footnote) you will

find that dividing GDP per capita by 365 days will let you

arrive at a higher value than the income that is determined

in household income surveys.

24

Billions of

people live in countries where average incomes are very low

The income

of every person depends on two factors, the average income

in the country they live in and the position that particular

person has in that country's income distribution.

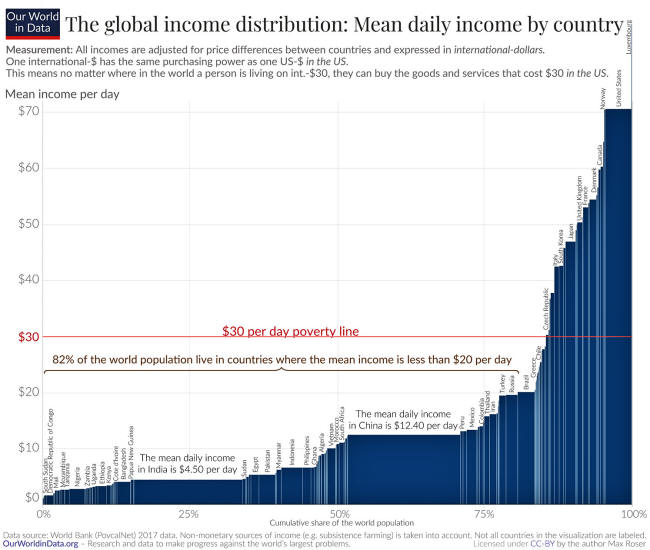

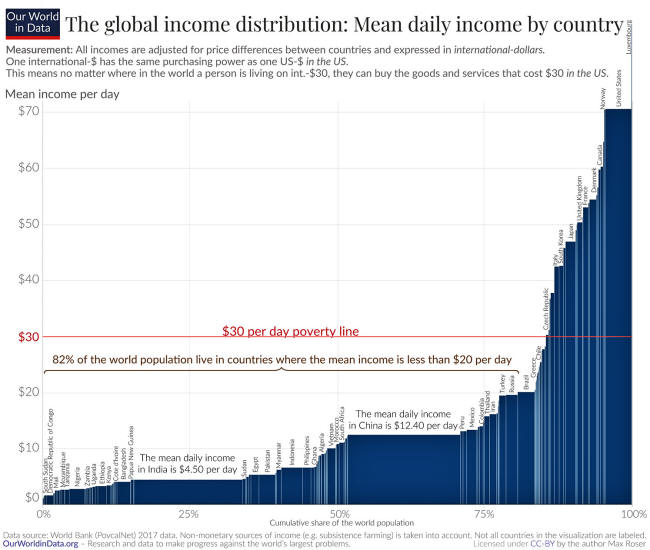

This chart

here shows the average income in countries around the world.

The height

of each bar represents the average daily income in a

country, the width of each country corresponds to the

country's population size.

I have

ordered the countries by income:

from

the poorest country on the very left (South Sudan where

the average person lives on $1.12 per day) to the

richest country on the very right (Luxembourg with an

average of $86 per day).

After two

centuries of economic growth the average income in Denmark

is now $57 per day today.

You find

the country far to the right in this chart, which tells you

that only very few countries in the world have such high

average incomes. The fact that the average income is far

higher than the poverty line tells us that the existing

poverty in Denmark discussed at the beginning of this post

is to a large extent the consequence of inequality.

What this

chart makes very clear is how low the average incomes in

many countries in the world are. The huge majority of the

world live in countries where the average income is

much lower than the poverty threshold in rich countries.

82% of the

world population live in countries where the mean income is

less than $20 per day. And where incomes are low, living

standards generally

are poor.

As the last

chart below shows, a child that is born into a poorer

country must not just expect to live on a very low income,

but also faces a much higher risk of not staying alive at

all.

As I have

said before, people are not poor because of who they

are, but because of where they are.

This is why

economic growth is so important to leave poverty behind. By

far the most important difference between those people who

are not living in poverty and those who do is the average

income in the country that they live in this single factor

matters more for a person's income

than all other factors taken together.

The

increase of average income in a country is called economic

growth and for global poverty to decrease substantially

economic growth for the poorest billions of people is

necessary.

The future of

global poverty

The world

today is far away from the 'end of poverty' relative to

any poverty definition.

After two

centuries of

unprecedented progress against the very worst poverty it

is still the case that every tenth person lives on less than

$1.90 per day.

As the

world has not even ended extreme poverty it is therefore

right to focus much of our attention on this very low

poverty cutoff; ending extreme poverty surely is a global

goal of great importance.

Yet at the

same time we should consider what our aspirations for the

future are. In the past our ancestors

did not know that it is possible for a society to leave

widespread poverty behind. Today we are in a different

situation.

We know

from the reality of today's rich countries that widespread

poverty is not inevitable.

Because we

know that poverty relative to such higher cutoffs is not

inevitable I believe it would be wrong to limit the

ambitions to eradicating poverty based on the definition of

poverty in the very poorest countries.

What I take

away from this discussion are three insights:

First,

we have seen from countries like Denmark that it is

possible to reduce poverty for an entire population

relative to a poverty line of about $30 per day.

Second,

we have seen that these countries were extremely poor in

the past and were able to reduce poverty over the course

of the last few generations.

And

third we have seen that the huge majority of the world

is still living in great poverty, by any standard.

What this

suggests to me is that the history of global poverty

reduction has only just begun...

Endnotes

-

Brønnum-Hansen

H, Foverskov E, Andersen IIncome inequality in life

expectancy and disability-free life expectancy in DenmarkJ

Epidemiol Community Health 2021;75:145-150.

https://jech.bmj.com/content/75/2/145

-

For the

moment it is important to note that this $30 per day poverty

line is defined in international-$ and therefore comparable

with the 'International Poverty Line' discussed in the

following section. Much more details about how to compare

incomes across countries, the income concept here, and the

definition of this poverty line follows further below in

this text.

-

Before the

pandemic

9% lived below this poverty line. Due to the global

recession the share in extreme poverty is expected to

increase this year to over 10%.

-

Kate

Raworth (2017) A Doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity's

compass in the 21st century. In The Lancet Planetary Health.

Volume 1, Issue 2, E48-E49, May 01, 2017. Open Access DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30028-1 You find

the metrics that the Doughnut relies on

in the Appendix here.

Jason Hickel

Could you live on $1.90 a day? That's the international

poverty line and

here.

Allen, Robert C.(201). Absolute Poverty: When

Necessity Displaces Desire. American Economic Review,

107 (12): 3690-3721.DOI: 10.1257/aer.20161080

-

Lant

Pritchett (2013) Monitoring progress on poverty: the case

for a high global poverty line. Online here

https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8440.pdf

-

Jolliffe

and Prydz (2016)

-

Specifically, the line is set at the average national

poverty line amongst 15 particular low-income countries. As

Jolliffe and Prydz (2016) demonstrate however, this is also

the average poverty line found among in the poorest quarter

of countries with available data, and also among countries

falling into the World Bank's low-income category.

-

The study

on which these thresholds rely is Jolliffe, D., Prydz, E.B.

Estimating international poverty lines from comparable

national thresholds. J Econ Inequal 14, 185–198 (2016).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-016-9327-5 The

researchers also report an average high-income country

poverty line of $21.70 per day.

High income countries in the World Bank framework are

however relatively poor compared to the countries that I'm

focusing on here the cutoff for a high-income country

according to the World Bank is $12,536, about a quarter of

the GNI of Germany and only a fifth of the US. Accordingly

the poverty cutoff is much lower than in those countries.

Here you find the World Bank income classification cutoffs.

-

The range

of incomes considered 'middle' and 'high' income countries

according to the World Bank are very low relative to rich

countries. High-income economies are those with a GNI per

capita of $12,536 or more. The range of middle-income

economies begins at a GNI per capita of $1,036. In this post

I want to rely on countries like Denmark; higher income

countries by any standard.

-

Martin

Ravallion (2019)

On Measuring

Global Poverty. NBER Working Paper 26211. DOI

10.3386/w26211

-

This is

possible by relying on the work of the

International Comparison Project, which monitors the

prices of goods and services around the world.

-

Angus

Deaton and Alan Heston (2010) discuss the methods behind

such price adjustments and many of the difficulties and

limitations involved.

Deaton, A.,

and Heston, A. 2010. "Understanding PPPs and PPP-Based

National Accounts." American Economic Journal:

Macroeconomics 2 (4): 1–35. A working paper version is

available online

here.

-

Keep in

mind that in the special case of the US the US-$ equals the

international-$.

-

The

European reference incomes are national median equivalised

disposable income after social transfers.

The

disposable household income including all income from work

(employee wages and self-employment earnings), private

income from investment and property, transfers between

households, and all social transfers received in cash

including old-age pensions.

Eurostat

applies an equivalisation factor calculated according to the

OECD-modified scale first proposed in 1994. The UN/World

Bank is not.

This is

according to Eurostat

here, where you also find the relevant data. (If the

link should break, search on Google for 'Distribution of

income by quantiles EU-SILC and ECHP surveys'.)

There are

various ways of bringing the national poverty lines with

reference to the national median equivalised disposable

income after social transfers in line with the

income/expenditure concept used in PovcalNet.

Joliffe and

Prydz follow a different approach and their paper is very

relevant for anyone interested in this question here. One

alternative to the approach I'm following in this article

would be to start from the poverty lines they estimated

(based on the poverty headcount ratio) and apply the growth

rate of the median income since the publication of their

study. Yet another possibility would of course be to repeat

their analysis with the up-to-date data. I am not following

either of these approaches because I believe for a wide

audience they are less transparent that the approach here which is simply: I rely on the same dataset so that I rely

on the same income concept, then look up the median income

and multiply it by 0.6.

This is the

reference: Jolliffe & Prydz (2016). Estimating international

poverty lines from comparable national thresholds. The

Journal of Economic Inequality, 14(2), 185-198.

–––

The

following are the relevant calculations. All of them are

based on PovcalNet data:

Germany's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1417.29 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

0.6*$1417.29=$850.374/30=$28.35 per day

Sweden's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1469 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1469)/30=$29.38 per day

Norway's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1890 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1890)/30=$37.8 per day

Austria's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1534 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1534)/30=$30.68 per day

In the

UK the median monthly income in 2017 was

$1252 according to PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1252)/30=$25.04 per day

France's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1364 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1364)/30=$27.28 per day

Switzerland's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1791 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1791)/30=$35.82 per day

Spain's median

monthly income in 2017 was $982 according to PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*982)/30=$19.64 per day

Iceland's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1582 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1582)/30=$31.64 per day

Luxembourg's

median monthly income in 2017 was $2193 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*2193)/30=$43.86 per day

Netherland's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1430 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1430)/30=$28.6 per day

Belgium's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1346 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1346)/30=$26.92 per day

Denmark's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1453 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1453)/30=$29.06 per day

Ireland's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1234 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1234)/30=$24.68 per day

Finland's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1361 according to

PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1361)/30=$27.22 per day

-

According

to the "Annual

Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines" the poverty line

in the US is an annual income of US$12,760. [And

12,760/365.25=$34.95.]

-

The

US median monthly income in 2017 was $1640

according to PovcalNet.

60% of the median expressed in daily income/consumption is

(0.6*1640)/30=$32.8 per day

-

These

reports are called 'Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der

Bundesregierung' online at

armuts-und-reichtumsbericht.de

The latest

survey was produced by aproxima and published in 2016. It is

published as

Wahrnehmung von Armut und Reichtum in Deutschland,

Ergebnisse der repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung „ARB-Survey

2015", Berlin: Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales

(Hrsg.).

-

The 2011

PPP conversion factor for private consumption (LCU per

international $) for Germany in 2015 is 0.84 according to

the World Bank

here.

This means

the perceived poverty threshold corresponds to

€947/0.84=int. $1,127.38 per month or int. $37.58.

-

The 2011

PPP conversion factor for private consumption (LCU per

international $) for Germany in 2017 is 0.83 according to

the World Bank

here.

This means

the UBI corresponds to 1200/0.83=int. $1,445.78 per month or

int. $48.19.

-

That's

€783/0.834=int. $938.85 per month. Or

int. $938.85/30.5=int. $30.78

per day.

-

Kahneman

and Deaton (2010) High income improves evaluation of life

but not emotional well-being. Published in the Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences. https://www.pnas.org/content/107/38/16489

-

Kahneman

and Deaton analyze two different concepts self-reported

satisfaction:

- Emotional

well-being refers to the "emotional quality of an

individual's everyday experience the frequency and

intensity of experiences of joy, stress, sadness, anger, and

affection that make one's life pleasant or unpleasant."

- Life

evaluation refers to the thoughts that people have about

their life when they think about it.

The authors

find that higher incomes go together with higher

self-reported life satisfaction in both metrics. What they

emphasize is that at very high incomes this is not true

anymore emotional well-being does not increase over around

$75,000. Evaluation of life however continues to increase

even at incomes over $75,000.

-

The two

previous ones were income/expenditure as determined in

household surveys and equivalised disposable income after

social transfers.

-

There is

generally a gap between GDP per capita and the averages

found in both income surveys and expenditure surveys. But

the reasons for the gap are different depending on which we

are comparing.

GDP

includes many items that are typically not measured in

household income surveys, such as an imputed rental value of

owner-occupied housing, the retained earnings of firms and

taxes on production such as VAT. The gap is even larger when

GDP is compared to surveys of household consumption the

latter concept excluding both investment expenditure and

government expenditure on public services such as education

and health.

Other

aggregates beyond GDP are available in the national accounts

that are more comparable to the concepts applied in

household income and consumption surveys. However important

differences still remain even here. For example, in addition

to imputed rents, imputations for the value of certain

financial services, such as bank accounts, are included in

aggregate household consumption measured in national

accounts, with no equivalent for these items recorded in the

survey data. In many countries the consumption of 'nonprofit

institutions serving households' (NPISH) is included as part

of household consumption within national accounts, but not

within household surveys.

On top of

these conceptual differences are a range of mismeasurement

problems that affect both sets of data. On this topic see

Deaton (2005), and Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin (2016).

Deaton,

Angus. 2005. "Measuring Poverty in a Growing World (or

Measuring Growth in a Poor World)." The Review of Economics

and Statistics 87 (1): 1–1.

Pinkovskiy,

Maxim, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2016. "Lights, Camera…

Income! Illuminating the Nation"

|