|

by

Samantha Pearson

and

Luciana Magalhaes from WSJ Website

patrolled a beach in Rio de Janeiro in June.

Mauro

Pimentel/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

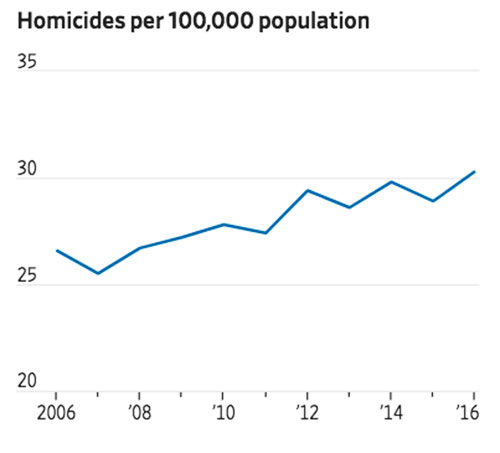

Shaken by violence, thousands of TV stars, bankers, lawyers and wealthy Brazilians are fleeing the country...

Wealthy Brazilians are

fleeing the country, terrified by spiraling gun violence and

pessimistic about the nation's political and economic future.

For months, the 40-year-old actor has been agonizing over whether to move his family to Europe for the safety of his three young children.

Unlike Central Americans fleeing to the U.S. because of gang violence or in search of work, these Brazilians are often members of the country's elite,

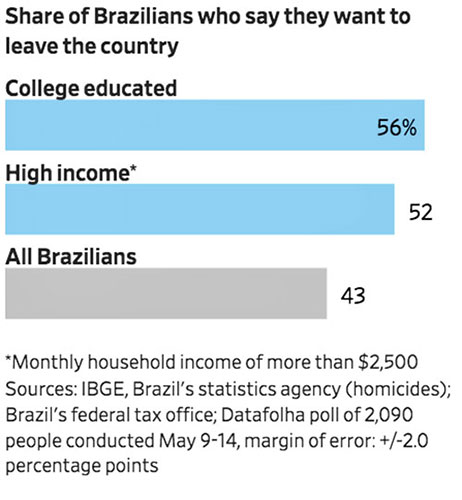

About 52% of the richest Brazilians - those with a monthly household income of more than $2,500 - want to emigrate, while 56% of college-educated Brazilians want to leave, according to a study published in June by Brazilian polling agency Datafolha.

Overall, 43% of Brazilians would emigrate if they could.

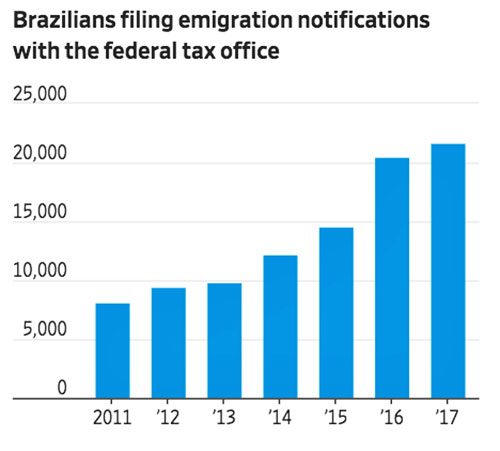

Brazil's government has struggled to keep track of how many of its citizens live abroad, but a series of recent studies paint a dismal picture.

With the October

presidential elections approaching, 41% more Brazilians have

registered to vote from abroad than in 2014, according to government

figures.

Many are moving to

exclusive enclaves on the Portuguese Riviera and to U.S. cities such

as Orlando and Miami.

In the affluent Urca

neighborhood, where locals go to watch the sunset, six dead bodies

recently washed up on the rocks.

A couple of months later,

he said his father was held up by gunmen.

About 62% of 16- to

24-year-olds would emigrate if they could, according to

Datafolha.

For those with a good

education, leaving "looks like a good decision," he said.

But Portugal, the colonial motherland, is fast becoming Brazilians' so-called Plan B.

There are now 85,000

Brazilians living in Portugal, the largest community of foreign

nationals, including many retirees lured by tax incentives,

Portugal's immigration and border service said.

The U.K. is another

popular choice, as is Switzerland - the adopted home of Brazil's

richest man, Jorge Paulo Lemann, who relocated there in 1999

after gunmen tried to kidnap his children on the way to school in

São Paulo.

Joseph Williams, a U.S. businessman who moved to Brazil eight years ago, said Brazilians can't understand why he is still here.

Only this week in São Paulo, where he runs a real-estate advisory and investment firm, two men robbed the drivers in the car next to his at the traffic lights.

But for many Brazilians, leaving is the last resort.

Still, for Mr. Melo, the e-commerce manager, life in Portugal has more appeal.

He is looking forward to simple things, like being able to answer his cellphone in the street - something he said he no longer does in Rio for fear of it being stolen.

at Copacabana beach in Rio in April. Photo: Erbs Jr./AGIF/Associated Press

|