|

by

Jessica Corbett

November 21, 2018

from

CommonDreams Website

The Xingu River flows near the area

where

the Belo Monte dam complex is under construction

in the

Amazon basin on June 15, 2012 near Altamira, Brazil.

The

controversial project is opposed by many

environmentalists and indigenous groups.

(Photo:

Mario Tama/Getty Images)

"We have come

from the forest

and we worry

about what is

happening"...

Alarmed by rampant

destruction in the Amazon rainforest and the long-term impacts on

biodiversity, an alliance of indigenous communities pitched the

creation of the world's largest protected area, which would reach

from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean, at a

United Nations conference in Egypt

on Wednesday.

"We have come from

the forest and we worry about what is happening," declared

Tuntiak Katan, vice-president of COICA, the alliance.

"This space is the

world's last great sanctuary for biodiversity. It is there

because we are there. Other places have been destroyed."

COICA, which represents about 500

groups across nine countries and is seeking government-level

representation at the U.N. Convention on Biodiversity, aims

to safeguard a,

"sacred corridor of

life and culture" about the size of Mexico.

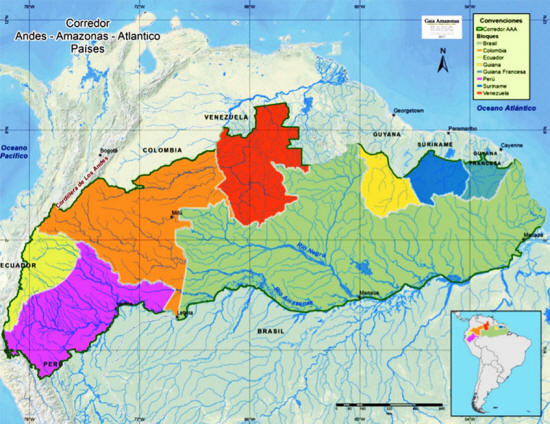

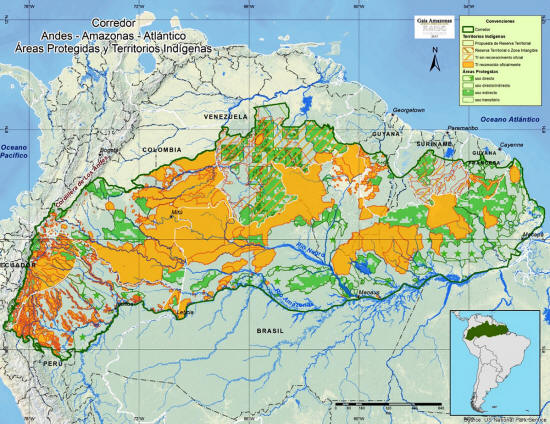

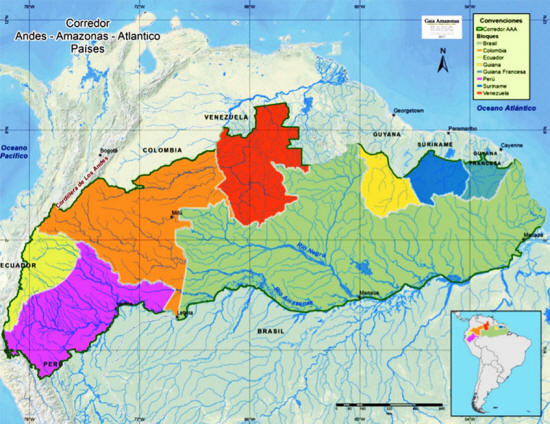

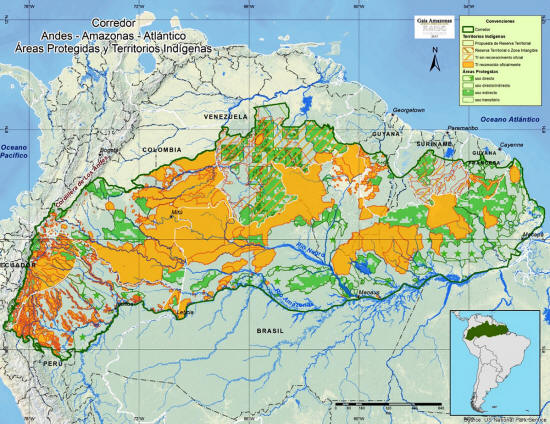

The alliance hopes to implement an "ambitious" post-2020 regional

plan to protect biodiversity in the Andes-Amazon-Atlantic or

"triple-A"

corridor from agribusiness, mining, and the global

climate crisis, but they are also concerned about territorial

rights, as they don't recognize modern national borders created by

colonial settlers.

The Andes, Amazon, Atlantic Corridor Project

source

"Indigenous

communities are guardians of life for all humanity, but they are

in danger for protecting their forest," Katan said. "We are

integrated with nature - it runs through our lives and we need

rights to defend it."

While fighting for the

right to defend the forest from development and the impacts of

global warming, the indigenous groups said they welcome

opportunities for collaboration.

Although Colombia had crafted a similar triple-A plan that was set

to be unveiled at next month's climate talks, as the Guardian noted,

"the election of new rightwing leaders in Colombia and Brazil has

thrown into doubt what would have been a major contribution by South

American nations to reduce emissions."

Outlining recent shifts in regional politics, the newspaper

reported:

Colombia's initial

proposal was smaller and focused only on biodiversity and

climate. But government enthusiasm has waned since an election

in June in which the rightwing populist Iván Duque took power.

Brazil was more

skeptical but had previously engaged in

ministerial-level talks on the corridor-plan. Its opposition is

likely to grow under its new rightwing president, Jair Bolsonaro,

who will take power in January.

Last month

Jair Bolsonaro

indicated he would only stay in the Paris climate agreement if he

had guarantees ensuring Brazilian sovereignty over indigenous land

and the "triple-A" region.

Source

Bolsonaro's comments about environmental and indigenous issues on

the campaign trail,

"are concerning

because they nurture a disturbing tendency in different parts of

the world,

-

where almost three-fourths of environmental defenders

assassinated in 2017 were indigenous leaders

-

where opposing agro-industry is the main cause for assassination of our leaders

worldwide

-

where imposing projects on to communities without

their free, prior, and informed consent,

...is at the root of all

attacks to indigenous and community leaders," said Juan Carlos Jintiach of COICA.

"Likewise, we see that it is increasingly frequent for

indigenous peoples and communities to face costly and difficult

processes to legalize their lands, while corporations obtain

licenses with ease," Jintiach noted, calling on Bolsonaro to

obey all laws and ensure the rights and safety of the people of

Brazil.

Despite the changes to

the local political climate, Katan vowed the indigenous communities

will keep working to play a key role in protecting the forest.

"We know the

governments will try to go over our heads," he said. "This is

nothing new for us. We have faced challenges for hundreds of

years."

"Indigenous peoples and local communities are a solution to the

devastation of our ecosystems and climate change both in the

Amazon as well as in the rest of the world," Katan added in a

statement.

"But whether policies

addressed at mitigating climate change and promoting the

restoration of rainforests succeed, depends on the security of

having possession of community lands."

|