|

by Clara Denina and Sarah Mcfarlane

Additional

reporting by Kate Abnett in Brussels, Christoph Steitz in Frankfurt,

Josephine Mason, Mark

John, Richa Naidu and Pratima Desai in London,

Michael Shields in

Zurich and Angeliki Koutantou in Athens.

November 02, 2022

from

Reuters Website

Italian version

A worker walks at the Yara ammonia plant

in

Porsgrunn, Norway August 9, 2017.

Picture

taken August 9, 2017.

REUTERS/Lefteris Karagiannopoulos/File Photo

A general view of the German chemical company,

BASF

Schwarzheide GmbH in Schwarzheide, Germany,

December 10, 2019.

REUTERS/Annegret Hilse

LONDON, Nov 2

(Reuters)

Europe needs its

industrial companies to save energy amid soaring costs and shrinking

supplies, and they are delivering - demand for natural gas and

electricity both fell in the past quarter.

It is far too early to rejoice, though.

The drop is not just

because industrial companies are turning down thermostats, they are

also shutting down plants that may never reopen.

And while lower energy use helps Europe weather the crisis sparked

by Russia's war in Ukraine and Moscow's supply cuts, executives,

economists and industry groups warn its industrial base may end up

severely weakened if high energy costs persist.

Energy-intensive industries, such as aluminium,

fertilizers, and chemicals are at risk of companies

permanently shifting production to locations where cheap energy

abounds, such as the United States.

Even as an unusually warm October and projections

of a mild winter helped

drive prices lower, natural gas in the United States still costs

about a fifth what companies pay in Europe.

"A lot of companies are just quitting

production," Patrick Lammers, management board member at

utility E.ON (EONGn.DE)

told a conference in London last month.

"They actually demand destruct."

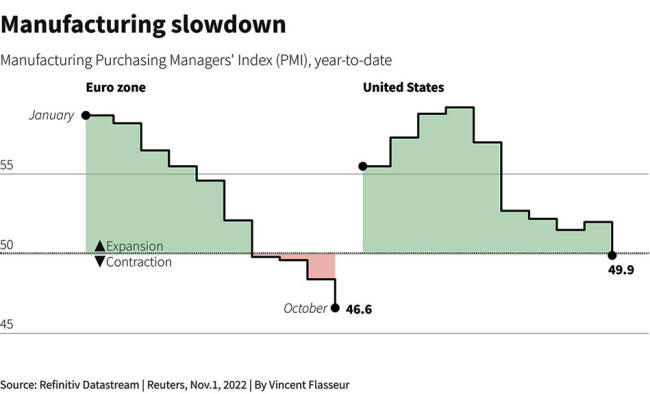

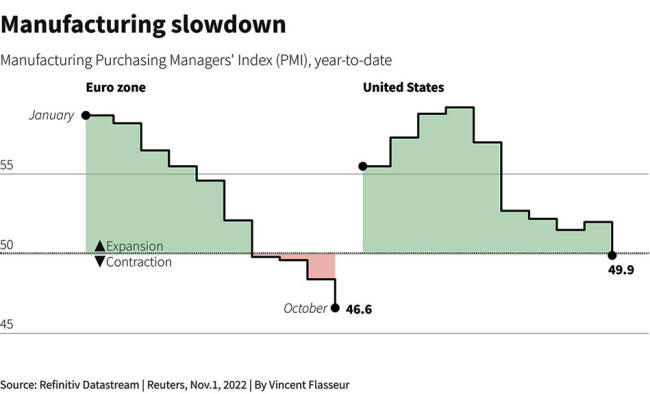

Euro-zone

manufacturing activity this month hit its weakest level since

May 2020, signaling Europe was heading for a recession.

Reuters Graphics

The International Energy Agency estimates

European industrial gas demand fell by 25% in the third quarter from

a year earlier.

Analysts say widespread shutdowns had to be

behind the drop because efficiency gains alone would not produce

such savings.

"We are doing all we can to prevent a

reduction in industrial activity," an European Commission

spokesperson said in an email.

But a

survey released on Wednesday showed companies in Europe's

industrial powerhouse Germany were already scaling back because of

energy costs.

More than one business in four in the chemicals

sector and 16% in the auto sector said they were being forced to cut

production, a survey of 24,000 businesses by the German chambers

of commerce and industry (DIHK) showed.

Moreover 17% of auto sector companies said they

were planning to move some production abroad.

"The effects are clearly visible:

energy-intensive producers of intermediate goods in particular

are cutting back on production," said DIHK Managing Director

Martin Wansleben, referring to critical semi-finished

products, such as chemicals and metals.

EXODUS FEARS

European industry has been shifting production to

locations with cheaper labor and lower other costs for decades, but

the energy crisis is accelerating the exodus, analysts said.

"If the energy prices stay so elevated that

part of European industry becomes structurally uncompetitive,

factories will shut down and move to the U.S. where there is an

abundance of

cheap shale energy," said Daniel Kral, senior

economist at Oxford Economics.

For example, EU primary aluminium output was

halved, cut by 1 million tonnes, over the past year.

Trade figures compiled by Reuters show all nine

zinc smelters in the bloc have either cut or stopped production,

which was replaced by imports from,

China, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Russia...

Reopening an aluminium smelter costs up to 400

million Euros ($394 million) and is unlikely given Europe's

uncertain economic outlook, Chris Heron at industry

association Eurometaux said.

"Historically, when these temporary closures

happen, permanent closures come as a consequence," he added.

Western efforts to secure supplies not just for

energy but also for key minerals used in electric vehicles and

renewable infrastructure are also at risk from high energy prices.

Brussels is expected to propose new legislation

early next year - the

European Critical Raw Materials Act

- to build up reserves of minerals indispensable in the transition

to green economy, such as lithium, bauxite, nickel, and rare earths.

But without more renewable power and lower costs,

companies are unlikely to invest in Europe, Emanuele Manigrassi,

climate and energy senior manager at

European Aluminium, warned.

Reuters Graphics

PACKING UP

Examples of industrial erosion are piling up...

Europe became a net importer of chemicals for

the first time ever this year, according to Cefic, the

European Chemical Industry Council.

More than half of European ammonia

production, a key ingredient in fertilizers, has shut, and has

been replaced by imports, according to the International

Fertilizer Association.

Norwegian fertilizer maker Yara (YAR.OL)

is utilizing around two-thirds of its European ammonia

production capacity.

"We are watching the situation in the gas

market closely and are making contingency plans," CEO

Svein Tore Holsether told Reuters via email.

Last week, the world's largest chemical group

BASF (BASFn.DE),

questioned whether there was a business case for new plants

in Europe.

The company has also warned it would have to

shut production at its main Ludwigshafen site - Germany's

single-biggest industrial power consumer - if gas supplies fall

below half of its needs.

Some firms, including German viscose fibre

maker Kelheim Fibres which supplies Procter & Gamble

(PG.N),

are looking to

other energy sources.

This year, the German company has cut output

twice at its factory in Bavaria.

"From Jan. 1, we will be able to switch

to oil," company executive Wolfgang Ott said, as the

company seeks government help to cushion energy costs.

It is even pondering a 2 megawatt solar

project.

In Greece, Selected Textiles, a small

cotton yarn producer, has cut output as orders mainly from

northern Europe have fallen.

At its plant in Farsala, central Greece, CEO

Apostolos Dontas estimated production would fall 30% this

year.

"We see our clients (...) are seriously

concerned whether there will be an equivalent consumption of

finished products in Europe and whether northern European

manufacturers themselves will have access to natural gas,"

he told Reuters.

Tata Chemicals (TTCH.NS),

which usually operates on a five-year plan, is now working on a

quarterly basis, its Europe managing director Martin Ashcroft

said.

"If this is a structural change and gas

prices stay high for three or four years, the real risk is

industry investment will be directed elsewhere to places

with lower energy prices," Ashcroft added.

|