|

11 September 2019 citation data are locked inside proprietary databases.

Credit:

iLexx/Getty want to make their own decisions about how to interpret citation metrics.

That requires data to be freely accessible...

As we report this week,

the publisher

Elsevier has been

investigating cases in which

reviewers have repeatedly asked authors of papers to cite the

reviewers' own work.

Last month, we reported

that some 250 highly cited scientists had amassed more than half of

their citations from their own work or that of co-authors - much

more than the usual proportion for their field or career stage (see

Nature 572, 578–579; 2019).

It was refined by the anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, and states that,

One obvious answer is for institutions and funders to just stop using citation-based metrics as a proxy for importance or quality when assessing researchers.

...one reader exclaimed in response to an online poll in Nature last month, in which we asked what - if anything - needed to be done to curb excessive self-citation.

Metrics-based analysis

can certainly reveal useful insights about research. But any

assessment procedure that rewards scientists according to

citation-based metrics alone seems designed to invite game-playing.

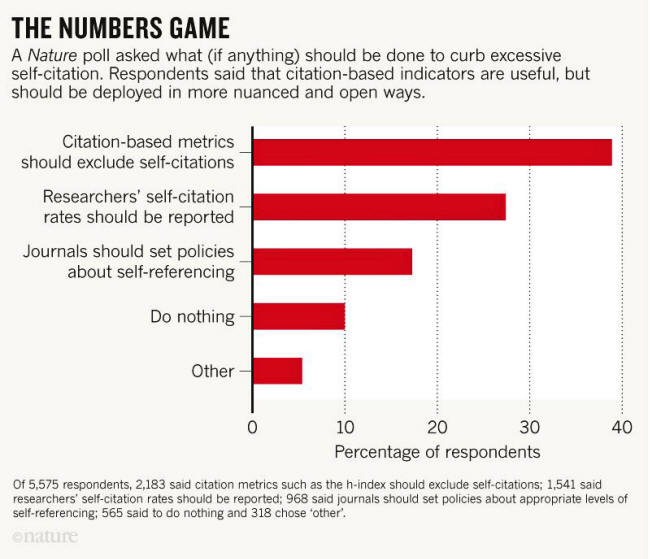

Of the more than 5,000 readers who answered Nature's poll, 10% said nothing needed to be done.

However, most poll respondents felt that citation-based indicators are useful, but that they should be deployed in more nuanced and open ways.

The most popular responses to the poll were that citation-based indicators should be tweaked to exclude self-citations, or that self-citation rates should be reported alongside other metrics (see 'The numbers game' - below image):

On the whole, respondents wanted to be able to judge for themselves when self-citations might be appropriate, and when not; to be able to compare self-citation across fields; and more.

Since 2000, more and more publishers have been depositing information about research-paper references with an organization called Crossref, the non-profit agency that registers digital object identifiers (DOIs), the strings of characters that identify papers on the web.

But not all publishers

allow their reference lists to be made open for anyone to download

and analyze - only 59% of the almost 48 million articles deposited

with Crossref currently have open references.

Last January, I4OC co-founder David Shotton at the Oxford e-Research Centre, University of Oxford, UK, urged all research publishers to join the initiative (see Nature 553, 129; 2018).

They should...

Excessive self-citation cannot be eliminated, but free access to citation data for everyone - researchers and non-researchers - will help to illuminate some darker corners.

Without more journals

coming on board, these necessary efforts to analyze self-citation

data will remain incomplete.

|