|

by Christopher

McIntosh

New Dawn

Special Issue,

Vol. 16,

No 5

October

2022

from

NewDawnMagazine Website

Russian philosopher

Alexander Dugin

Russia gets into your blood. It got into mine when I studied Russian

at the United Nations Language School in New York in the

1980s and 90s while working as a UN information officer, having

already learned the basics when I was 19.

I can still hear our teacher Alla coming into the classroom

and saying:

"Today, my dear

students, we going to study our beautiful Russian verbs - first

the imperfective and then the perfective verbs."

Who could fail to fall in

love with Russian verbs with such a charming teacher?

If you happen to read

this, Alla, I send you a big wave. But it was not only the verbs...

Other intricacies of

Russian grammar intrigued me, rules like,

"don't forget that if

the verb is negative the noun has to be in the genitive."

And the beautiful

Cyrillic alphabet would dance before my inner eyes.

Then there was my Russian

girlfriend around the same time, who told me that,

"to sound like a

Russian you must smile inwardly when you speak."

Indeed, they do this even

when they are conveying something sad or, more likely, sad and funny

at the same time - a combination at which the Russians excel.

Russian literature, too, captivated me.

I became familiar with

Dostoyevsky's Idiot, Andrei Bely's extraordinary

novel Petersburg and the equally extraordinary Master and

Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

Reading these works, one

becomes aware of the deeply spiritual nature of the Russian soul.

Furthermore, these last

two authors revealed another side to Russia that intrigued me,

namely a strong current of fascination for things magical, esoteric

and other-worldly.

I decided to go deeper

into this domain, and my latest book

Occult Russia was the result.

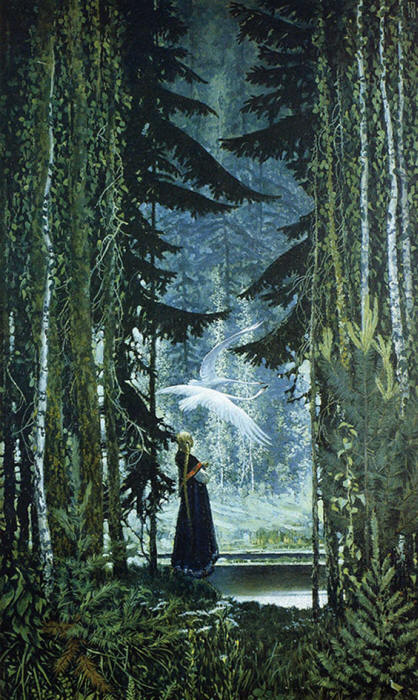

'Ilya Muromets' (1910)

by

Nicholas Roerich.

Of course, I was devastated when the war in the Ukraine began, and I

feel deeply for all my Russian and Ukrainian friends.

As I write I can only

pray that the conflict will not be prolonged. As a stop-press item,

I must express my deep outrage and sadness at the death of

Alexander Dugin's daughter Darya who was killed on 20 August

2022 by a car bomb possibly intended for her father.

Through this cowardly

act, the life of a radiant human being has been tragically cut

short.

My deepest sympathy

goes out to all her family.

I offer the book

Occult Russia in the hope that it will contribute to a deeper

understanding of the Russian mind and soul.

What follows is a

foretaste of it, abridged and edited from the Introduction...

• • •

Upon hearing the word "Russia" you may think of,

military parades in

Red Square, the war in the Ukraine, the annexation of the

Crimea, gangsters, internet hackers, assassinations of

journalists and imprisonment of opposition politicians...

This book is not about

those things but about a different Russia that is invisible to many

people in the West - namely the inner Russia, the Russia of

mysticism, myth, magic, the esoteric and the spiritual.

Like a vast river, long

ice-bound, the spiritual force deep in the Russian soul is moving

again.

In the wake of the

collapse of communism, the Russian people are seeking new - or often

old - ways of giving meaning to their lives. This search has given

rise both to a revival of ancient spiritual traditions and to a

plethora of new movements, cults, sects, -isms and -ologies, most of

which would have been banned in the Soviet era.

Out of this ferment

exciting things are emerging.

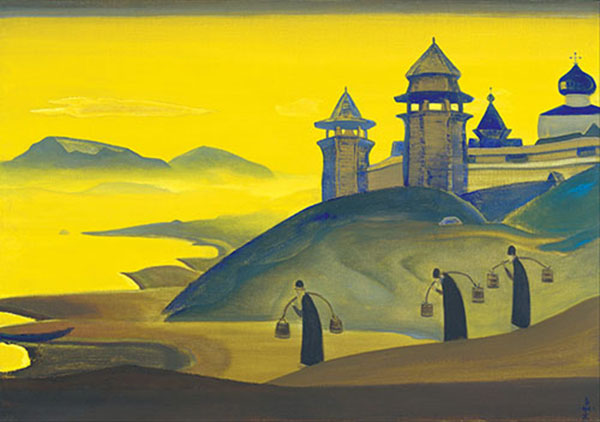

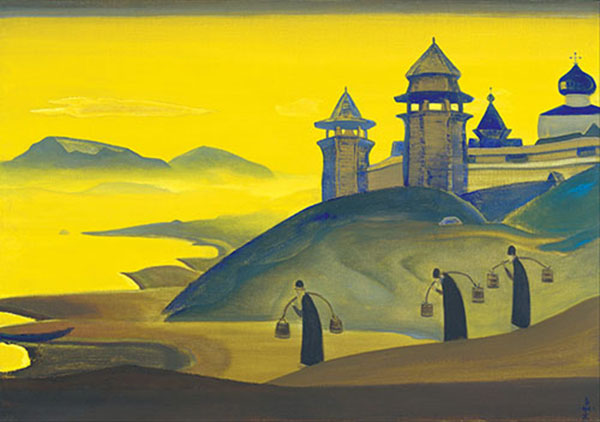

'And We are Trying' (1922)

by Russian artist and Eurasian mystic

Nicholas Roerich.

Today's spiritual quest in Russia covers an enormous spectrum.

Millions are turning or

returning to the Orthodox Church, and thousands of new churches are

being built. As for alternative forms of spirituality, many people

are turning to doctrines such as Theosophy, Anthroposophy and the

teachings of Nikolai and Helena Roerich.

Another group is turning

back to the pre-Christian gods of Russia or to

shamanism, often of the variety practiced by the urban

intelligentsia.

Meanwhile the indigenous

pagan communities such as

the Mari and the various shamanic

peoples of Siberia are enjoying a new lease of life.

In Russia the shamanic

and pagan traditions have long existed side by side with the

Orthodox religion - if not always in peaceful co-existence at least

in a modus vivendi that the Russians call dvoeverie

(dual faith).

History can be driven by mythical motifs, and this perhaps applies

particularly strongly to Russia. One useful term for such a motif is

the word "meme," coined by the British biologist Richard Dawkins

in his 1976 book 'The

Selfish Gene.'

Originally used in the

biological context, it has come to mean an idea or notion that

spreads like a message through a society, transmitted from person to

person or through the media.

A phenomenon with some similarities to the meme, but operating at a

deeper level, is that of the egregore, a collective

thought-form on the invisible plane, created by many people focusing

on the same ideas and symbols.

Deriving from a Greek

word meaning "watcher," an

egregore can take an infinite

variety of forms:

an angel or demon, a

god or goddess, a hero or heroine, an object of special

veneration, a sacred place or a compelling narrative...

The concept of the

egregore overlaps to some extent with the notion, developed by

the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, of the archetype,

an inherited motif in the collective unconscious of humanity.

In exploring Russia's

mystical quest we find various powerful memes, egregores

and archetypes at work.

They include the

following:

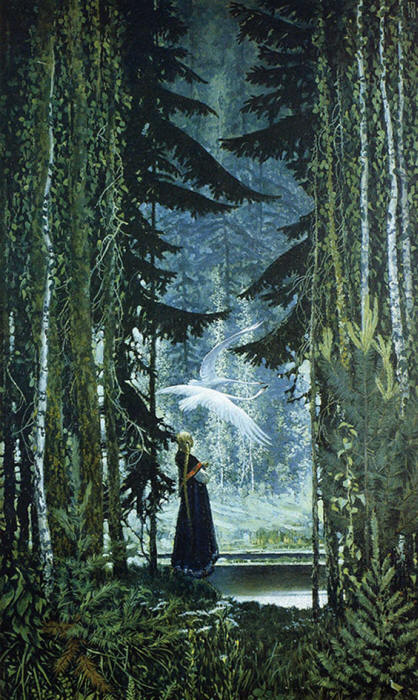

Holy Russia

Geese

by Konstantin Vasilyev

The notion of Holy Russia is searchingly explored by Gary

Lachman in his book of that title.

Deeply engrained in

the Russian collective soul is the conviction that Russia has a

special spiritual mission. This is reflected in the powerful

mystique of the Orthodox Church and the concept of the "Third

Rome":

the first Rome

being the city on the Tiber, the second being Constantinople

and the third and final one being Moscow.

All of this has given

rise to an egregore of enormous vitality, which has

enabled the Orthodox religion to flourish anew after the

communist era.

The Warrior

Hero

An early example of this figure is the semi-legendary Ilya

Muromets, who features in various Russian epics as well as

in films, novels and art.

Probably a composite

of various different people, he appears as a defender of Kievan

Rus in the 10th century and in later incarnations he

fought the Mongols and saved the Byzantine Emperor from a

monster.

He eventually became

a saint of the Orthodox Church.

The role of the

warrior hero has also been played by certain real historical

figures such as Prince Alexander Nevsky who defeated,

the Teutonic

Knights in the thirteenth century, Tsar Peter the Great, and

even Joseph Stalin...

The

Never-Never Land

This motif crops up repeatedly in Russian history in various

forms and under various names:

-

Byelovodye

(Land of the White Waters)

-

Opona, the

utopia of peasant folklore

-

Hyperborea,

the vanished promised land in the north

The Never-Never

Land is also thought of as the source of an ancient wisdom

tradition that has the power to transform human life if one

could only access it.

The

Rustic Sage

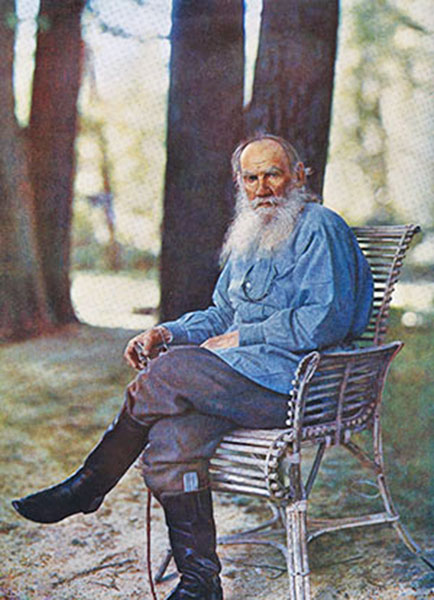

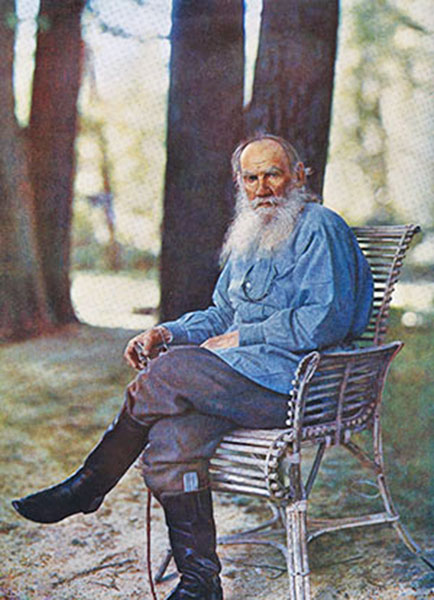

The

rustic sage,

Lev

Tolstoy,

pictured

at Yasnaya Polyana, 1908,

in

the first color photo portrait in Russia.

This figure is typified by Tolstoy's character of

Platon Karataev, the wise peasant who is a fellow

prisoner of the hero Pierre Bezukhov in War and Peace.

Tolstoy himself

adopted this persona in his later years.

The Holy

Fool

Alternatively "fool for Christ," this term is applied to someone

who adopts an apparently mad way of life, marked by great

austerity and extreme piety.

It can overlap with

the concept of the starets, the independent, god-illuminated

holy man or woman.

It has been pointed

out to me by my correspondent Dana Makaridina that there

are two kinds of holy fool, namely,

The distinction is

subtle.

The former are

characterized by a state of saintly bliss, whereas the

latter are conspicuous by their craziness and weird,

antisocial behavior.

Both are associated

with freedom, being unconstrained by any social norms and able

to communicate directly with God.

Dana Makaridina

mentions a friend who has had the nickname blazhennyi

since childhood because of his strange, otherworldly behavior.

She writes that,

"now he is an

extravagant rock musician and performance artist dealing

with topics of freedom and death."

The New

Messiah

Prophets and messiah figures have abounded in Russian history,

overlapping somewhat with the starets and the fool for

Christ, and they continue to appear in the present day.

A typical example is

the case of Sergei Anatoljewitsch Torop, an artist and

jack-of-all-trades who, in 1991, proclaimed himself to be

Jesus Christ returned.

Adopting the name

Vissarion, he founded a community called the Church of

the Last Testament, gathered several thousand followers and

established an eco-spiritual settlement in Siberia.

At the time of

writing he is in prison facing a charge of extorting money from

his followers and subjecting them to emotional abuse.

The Woman

Clothed with the Sun

This figure originates in a passage in chapter 12 of the book of

Revelation in the New Testament.

To quote the King

James Bible:

And there appeared a

great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the

moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars.

This image of the woman

clothed with the sun crops up repeatedly in Russian prophetic

writings.

My own perception of Russia has been through different stages. As

far as I can remember, the country meant little to me until 1953,

when I was nine years old, and one morning at breakfast my father

picked up the newspaper and remarked that Stalin had died.

I may have asked who

Stalin was and been told that he had been the leader of our powerful

eastern ally during the Second World War.

Later I absorbed the Cold War propaganda.

Russia came to mean,

-

the suppression

of the Hungarian uprising

-

defectors from

the West like Burgess and Maclean

-

Khrushchev

banging his shoe on the table at United Nations General

Assembly

-

the Cuban missile

crisis

-

the crushing of

the Prague Spring

-

the persecution

of dissidents...

At the same time I was

fascinated enough by Russia to start learning the language when I

was nineteen years old, a process that I resumed in my fifties, by

which time I had witnessed the advent of Gorbachev and

perestroika, shortly to be followed by the break-up of the Soviet

empire and the collapse of communism itself.

While these tumultuous

changes were going on I visited Russia for the first time in 1991

with an American contingent of very amiable born-again Christians,

whose tour group I was able to join through the facilitation of an

acquaintance.

A particularly vivid memory of that trip was visiting a Russian

Orthodox seminary near Saint Petersburg.

On entering the building

I found myself transported into another world, marked by candlelit

icons, the fragrance of incense and an atmosphere of still

reverence.

There was a quiet dignity

about the priests and seminarists moving about in the dim corridors.

One of them, looking

startling like the photographs I had seen of the wild-eyed prophet

Rasputin, was a young man with long, black hair and a solemn

expression, dressed all in black in a sort of peasant's tunic,

trousers, and boots.

We were shown to the

chapel of the seminary where a service was held, and I began to

understand why Madame Blavatsky, non-Christian though she

was, always vehemently defended the Orthodox Church.

At the present time, in the wake of the collapse of communism, the

Orthodox religion is once again playing a central role in the life

of the nation.

Churches are full,

and thousands of new ones are being built, with the state

playing a supporting role.

But not everyone is happy

with the current situation, and some of the initial post-perestroika

religious enthusiasm is waning.

Many believers oppose

what they see as an increasing tendency towards a merger of state

and Church, while people of other persuasions do not want Orthodox

Christianity to be imposed on the population.

Visiting Russia reinforced my view that it has a special destiny, as

many prophets have predicted. One of them, the German writer

Oswald Spengler, wrote in an essay entitled "The Two Faces of

Russia" (1922):

The bolshevism of the

early years has thus had a double meaning.

It has destroyed an

artificial, foreign structure, leaving only itself as a

remaining integral part.

But beyond this, it

has made the way clear for a new culture that will some day

awaken between "Europe" and East Asia. It is more a beginning

than an end.

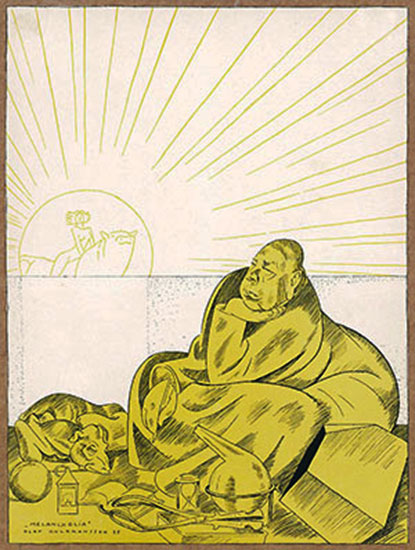

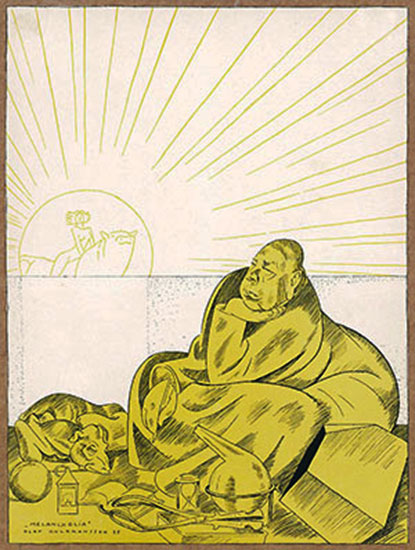

A 1930s

cartoon by Olaf Gulbransson,

caricaturing the German historian Oswald Spengler.

The woman in the background symbolizes Spengler's prediction

that

a new age will come out of Russia.

Property of the Olaf Gulbransson Museum, Tegernsee.

Photograph © VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022.

Thirteen years later Spengler's vision for Russia was illustrated in

a cartoon by the artist Olaf Gulbransson, which appeared in

1935 in a literary-satirical journal originally produced in Munich

under the name Simplicissimus, but by then published in exile

in Prague under the title Simpl.

The cartoon, entitled

Melancholia, is a parody of Albrecht Dürer's famous

engraving known under the same title.

In the foreground sits a melancholy Spengler, quill pen in hand,

beside an even more melancholy dog and various other objects

including an obstetric forceps, perhaps indicating that the New Age

in Russia will have a difficult birth.

In the background is an

image of the New Age itself in the form of a naked young woman

riding a rather complacent-looking bear, both framed in a large

rising sun.

The woman in the

background riding a bear symbolizes Spengler's prediction that a new

culture will come out of Russia.

Gulbransson's cartoon appeared in 1935 during a troubled time.

Germany had been through a military defeat, followed by the ravages

of inflation and depression and then by the Nazi seizure of power in

1933.

In Russia the Bolsheviks

ruled. Another war was on the horizon.

But Gulbransson pictured

a bright future coming from the direction of Russia and symbolized

by the maiden riding the bear.

Between then and now

there are certain parallels. The present era is overshadowed by war

and by high tensions between Russia and the West.

But I believe the maiden

riding the bear still carries a hopeful message.

References

|