|

by Ron Unz and Mike Whitney interview with Ron Unz...

I think the Western media has been overwhelmingly

biased against China, a bias that stretches back for decades but has

steadily grown worse during the 2010s and especially the last few

years.

Furthermore, much of our academic world has followed this same

pattern of totally distorting the reality of China and its

relationship with the U.S.

For example, the former Beijing bureau chief of the Washington Post personally covered those events at the time, and he later published a long article setting the record straight, but his account has always been ignored.

Articles published in the New York Times by its own Beijing bureau chief said much the same thing, but these also had no impact.

Numerous other sources, including secret American diplomatic cables disclosed by Wikileaks have confirmed these facts, but our biased, lazy, or ignorant journalists have never paid any attention and for decades continued to promote the myth of the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Last year I published a long article summarizing all of this evidence.

Another egregious example was the 1999 American bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, an illegal attack that killed or wounded nearly two dozen Chinese.

Our government and media have always described this as a tragic accident, while denouncing and ridiculing China for claiming that the bombing was deliberate.

But once again, there is overwhelming evidence that the Chinese government was entirely correct and our own government was lying, with our dishonest media endorsing and amplifying those lies.

Indeed, a NATO officer was even quoted in a leading British newspaper as bragging that the guided bomb had struck exactly the intended room in the embassy. I discussed this in another section of that same article.

A few years after America's 2008 mortgage meltdown nearly brought down the world financial system, I published a long article contrasting China's growing success with America's recent record of failure. My piece emphasized that the Western media and much of the Western academic world often portrayed and contrasted the two countries in ways that were the exact opposite of the reality.

As a short sidebar to that long article, I compared the very different Western coverage of a pair of major public health scandals.

In China, dishonest businessmen had adulterated baby food and other products with a plastic compound called melamine, protecting themselves by paying bribes to government officials. As a result, hundreds of infants were hospitalized with kidney stone problems and six died, resulting in a huge wave of public outrage and a massive government investigation and severe crackdown.

Many of those involved received long prison sentences and a couple of the guiltiest culprits were executed. Western media outlets naturally had a field day describing how widespread Chinese corruption had resulted in dangerous food products.

Nearly 17 years later, I sometimes still find Americans mentioning China's food scandal and the dangers of Chinese imports.

However, around the same time, America was hit with the Vioxx scandal, in which Merck heavily marketed a lucrative pain relief medicine to the elderly as a replacement for simple aspirin.

But Vioxx sales were suddenly halted when a government study showed that the medication had apparently been responsible for tens of thousands of American deaths.

Internal documents soon revealed that Merck executives had known of those dangers for years but suppressed the evidence in order to reap billions of dollars of profit from their drug.

American media companies had earned hundreds of millions of dollars in Vioxx advertising, so they quickly dropped the story and almost no Americans still remember it today.

Although no one was ever punished, when I later examined the underlying mortality data, I discovered that the true Vioxx death toll may have actually reached into the hundreds of thousands.

Thus, the American media devoted huge attention to a Chinese health scandal resulting in six deaths while quickly flushing down the memory-hole an American health scandal whose body-count may have been as much as fifty thousand times larger.

Therefore, today probably many times more Americans are aware of the former than of the latter.

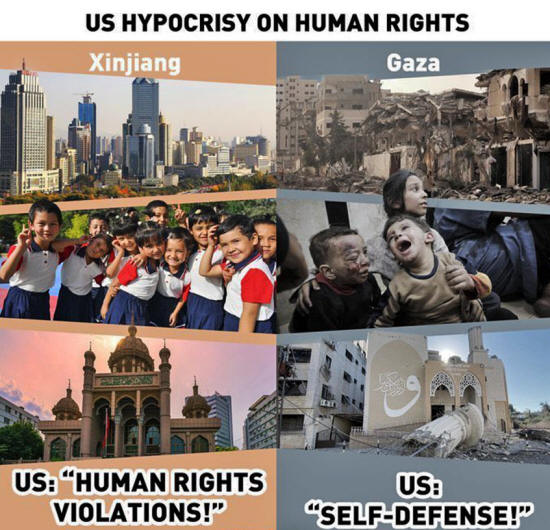

During the last few years, the media's anti-China propaganda has gone into complete overdrive, portraying that country as suffering under a horrible, oppressive dictatorship.

As an example, in January 2020, top officials of the outgoing Trump and the incoming Biden Administrations both declared that China was committing "genocide" against the Muslim Uighur population of Xinjiang province, and our media has regularly repeated and amplified those outrageous accusations.

Instead, many Westerners have who recently visited China or now live there have begun documenting their experiences in numerous YouTube videos, often very favorably comparing conditions in that country with those in America.

A common refrain of those YouTubers has often been,

Question 2: The Han Chinese People

The Han Chinese are by far the largest ethnic group in China, comprising an estimated 92% of China's population. In your opinion, is race or ethnicity a factor in China's success?

Ron Unz I do think that China's overwhelmingly Han Chinese majority population has been an important element in the country's national success in several different ways, but some of the key factors are not fully appreciated in the West.

First, because China's total population is over 90% Han, the country is far more ethnically homogenous and culturally unified than nearly any of today's Western countries.

Contrary to the West's dishonest anti-China propaganda, China's numerous ethnic national minorities are not harshly mistreated let alone the victims of cultural or physical "genocide."

But they are still only a very minor element in Chinese society, especially because they are mainly concentrated in outlying, often thinly populated provinces.

I think a reasonable analogy might have been the overwhelmingly white America of the 1950s but without blacks. Americans of that era certainly knew that various non-white minorities existed in their country, including Eskimos in Alaska, Hispanics in New Mexico and Puerto Rico, Asians in Hawaii, and some Hispanics and Asians in California.

But these were all very small groups, each amounting to only 1% or 2% of the total national population, so that most Americans never encountered them and considered their country's population as essentially white European.

Moreover, just as the overwhelmingly white America of the 1950s was divided into white regional groups, with New England whites different from Southern whites or Midwestern whites, the Han populations of the different Chinese provinces have traditionally spoken different regional dialects that actually amounted to different languages, while always using the same written form.

However, since the establishment of the PRC in 1949, younger Chinese have all learned the Mandarin dialect in the schools, an important step in strengthening national unity by ensuring that everyone could speak the same language.

Although Han Chinese think of themselves as a single people, to some extent they actually represent a fusion of different original groups who had existed prior to China's unification, with the example of the Roman Empire providing a reasonable analogy.

Around 2000 years ago, the Han Chinese Empire and the Roman Empire were roughly contemporaneous, but although Rome fell and its territories fragmented into numerous different states, the Chinese Empire survived and generally remained united during all the centuries that followed.

However, if Rome had never fallen, it's likely that all its different component peoples would have eventually come to regard themselves as "Romans," though with regional differences.

Thus, northern Romans might have generally been taller, with fairer skin, blond hair, and blue eyes, while the Romans of North African or the Levant would have been darker and shorter, with black hair and brown eyes. But all would have considered themselves Romans.

Similarly, northern Han tend to be taller than southern Han, and the different provinces - many of them as large as European countries - are often culturally different, traditionally spoke different dialects, and ate different foods, but they all regarded themselves as Han Chinese, though having differing regional characteristics.

But completely aside from China's Han ethnic unity, another very important reason for China's success has been its long and almost unbroken history as an organized, centralized state, which for thousands of years has been one of the most economically and technologically advanced parts of the world.

The resulting cultural and economic pressures have greatly shaped the Chinese people over those centuries, ultimately producing many of their current characteristics.

By contrast, much of today's Europe had never been a civilized part of the Roman Empire, and even those parts that were Roman later spent up to a thousand years living in the much more backward societies of the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages prior to the Renaissance.

The impact of this long legacy of civilized life in China was always noted by Western scholars.

In my articles, I have pointed out that although most Westerners of the mid-twentieth century were very skeptical of future Chinese success, our leading public intellectuals of a century ago had held entirely different views, and would hardly have been surprised by China's rapid economic advance in recent decades:

Thus, today's Han Chinese are the heirs to the shaping pressures of thousands of years of life in an organized, stable, but very economically challenging civilization.

Question 3: China's Competitive Economy

In your article, you say that China is a more competitive environment than the US which seems to indicate that China is more market-oriented than America. Can you explain what you mean by this?

Ron Unz Given the severe distortions about China frequently found in the Western media, we were very pleased to recently add a Chinese columnist named Hua Bin, a retired business executive who had established his own Substack, and published numerous informative posts regarding his own country and its sometimes troubled relationship with America.

Hua had originally caught my attention when he'd left a favorable comment on our website:

Given his business background, it was hardly surprising that many of his posts focused on economic matters, effectively debunking some of the misleading criticism of the Chinese economy.

For example, Hua noted that Western leaders often complain that many Chinese businesses are state-owned rather than private.

But he pointed out that this criticism seemed logically inconsistent.

America's reigning neoliberal dogma had always maintained that government-owned enterprises were inherently inefficient and uncompetitive, so denouncing China for having many such state-owned enterprises that were successfully outcompeting private Western corporations merely demonstrated the bankruptcy of that ideological framework.

Instead, he argued that the ultimate ownership structure of such companies mattered less than whether the marketplace in which they operated was sufficiently competitive, and in many sectors such heavy market competition was far more common in China than in America:

Hua argued that the severe consequences of such lack of market competition in America were most obvious in the military sector.

Thus, despite our gargantuan military spending, we have been completely unable to match Russia's far smaller economy in producing the munitions being expended in the Ukraine war:

Question 4: War Between the U.S. and China

Who would prevail in a war between the United States and China?

Ron Unz It obviously depends.

If China sent an expeditionary force to attack the West Coast of the U.S. or tried to occupy Canada or Mexico, our very short supply lines and our enormous numbers of land-based aircraft would doom the Chinese to a swift and certain defeat.

However, China has never been a militarily aggressive power and is extremely unlikely to launch such an attack.

Instead, any war fought between China and America would almost certainly occur under exactly the opposite conditions, taking place in the vicinity of the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea, locations that are very close to China but thousands of miles distant from the United States.

For that reason the outcome is likely to be very different.

In fact, China's entire weapons procurement policy and military strategy has been based upon the goal of deterring or if necessary defeating American armed forces operating in its own close vicinity.

I personally hope that such a disastrous military conflict can be avoided.

But over the last decade, the mainstream American media has regularly emphasized the likelihood of a war with China in the near future. A recent example was a lengthy late October article in the New York Times carrying the headline "The U.S. Army Prepares for War with China."

Therefore, quite a number of Hua's detailed posts focused upon the military implications of China's technological development and the weapons systems that China was creating.

He considered the recent record of America's aggressive wars as very threatening to his country, and he reasonably regarded a war as likely to occur:

Given these serious concerns, he summarized some of China's major advances in military technology in very detailed and precise terms.

A few days later Hua followed this up with a lengthy post entitled "Comparing War Readiness Between China and the US," and I found his overall analysis quite persuasive.

Once again, he began by emphasizing that a war seemed very likely:

He then focused upon the industrial factors that would be likely to dominate such a conflict, and China's strong superiority in that regard:

He also emphasized that the conflict would occur close to China but very far from the United States:

He noted that all of America's many wars since World War II have been fought against technically inferior opponents against which our military possessed enormous superiority and could operate with near total impunity.

However:

He also argued that China's national support for a war fought so close to its own homeland would be enormously greater than America's ideological commitment to its continued imperial adventure more than six thousand miles away in East Asia:

Finally, he pointed out that America's own military track record over the last three generations had hardly been impressive:

Therefore I found it very difficult to disagree with his ultimate conclusion:

Question 5: Comparing the Size of the Two Economies

Is GDP a reliable way of comparing the size of China's economy to America's?

Ron Unz The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) represents the total value of all the goods and services produced in a country, and is a useful means of comparing the size of two economies, but it must be treated carefully.

First, it's generally better to focus on GDPs that are adjusted for Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). These are based upon local prices, rather than relying upon nominal exchange rates.

For example, if China and America each produced a ton of steel of similar quality, the contribution to their nominal GDPs might be very different, while under the PPP adjustment the impact would be similar.

The use of PPP is sometimes called using "world prices" or "real prices" with the resulting PPP-adjusted GDP called "Real GDP."

Another, somewhat less common approach is to focus on the "productive GDP," namely the portion of the GDP that excludes the service sector.

Obviously, many service industries are absolutely necessary in a modern economy, and are just as legitimate and real as manufacturing, agriculture, construction, or mining.

But unfortunately service sector economic statistics are also far more easily manipulated, especially those involving the non-tradeable service sector.

Here's an example of what I mean.

Suppose that John and Bill each set up a diversity-coaching business, with John hiring Bill as a diversity-coach for a salary of $1 million per year, and Bill reciprocating by hiring John as a diversity-coach for the same annual salary.

Except for possible tax payments, no net money has changed hands and no net wealth has been created. But the size of the service sector GDP will have been boosted by $2 million per year, falsely suggesting a large increase in national prosperity.

Or consider a less ridiculous example. Parents normally look after their own children.

But suppose families instead swapped their children with their neighbors and hired the latter for that purpose. This would produce a huge apparent increase in service sector GDP without anyone gaining any actual economic benefit.

In one of his posts, Hua also noted that a related sort of phantom economic activity called "imputations" are already included in the U.S. GDP, which is therefore inflated as a result:

In addition, Hua pointed out that Western governments have sometimes even further inflated their GDPs by including criminal activity in their service economy:

But the GDP is intended to provide a means of measuring national economic prosperity, so including crimes such as prostitution, drug-dealing, burglary, and armed robbery in the service sector economy defeats the entire purpose of that metric and distorts our understanding of a country's economic situation.

The benefit of focusing upon the productive GDP excluding services has been emphasized by some noted academics.

Jacques Sapir serves as director of studies at the EHESS, one of France's leading academic institutions, and in late 2022 he published a short article making the case that focusing on real productive GDP removes all these potential distortions.

Therefore, he suggested that this probably produces a much more realistic estimate of the comparative economic strengths of different countries, including China and the U.S.

He argued that during periods of sharp international conflict, the productive sectors of GDP - industry, mining, agriculture, and construction - probably constitute a far better measure of relative economic power, and Russia was much stronger in that category.

So although Russia's nominal GDP was merely half that of France, its real productive economy was more than twice as large, representing nearly a five-fold shift in relative economic power.

This helped explain why Russia so easily surmounted the Western sanctions that had been expected to cripple it. Similarly, as far back as 2019, China's real productive economy was already three times larger than that of America.

These economic trends favoring Russia and China have continued over the last couple of years, and Russia's real productive economy has now surpassed that of both Japan and Germany to become the fourth largest in the world.

Meanwhile, China's lead over the nations of the West has steadily grown during that same period.

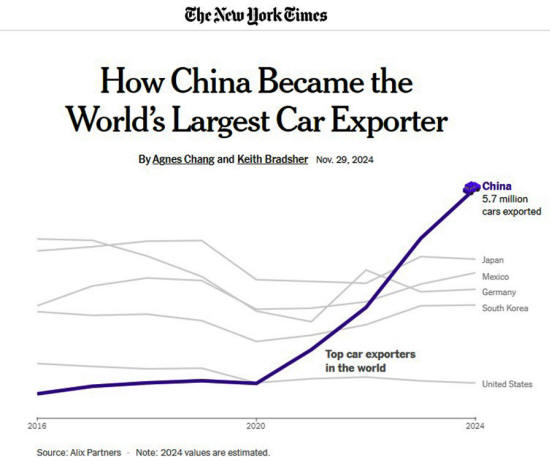

I recently noted that although the New York Times has run numerous wordy articles describing China's alleged economic stagnation, an actual chart it displayed suggested something extremely different:

As I explained:

Therefore, a few months ago I produced a table listing the size of the world's largest two dozen economies, including their nominal, real, and real productive figures.

All this data is drawn from the CIA World Factbook, which conveniently provides estimates of the 2023 real PPP-adjusted GDP for the countries of the world, as well as the most recent figures for the nominal GDPs, the economic sector composition, and the national populations.

Since some of these estimates come from slightly different years, I've rounded the values to emphasize that these statistics are merely approximations.

If we focus on the interesting metric of Per Capita Real Productive Income, we see that although the population of the Western bloc - the U.S., the EU, and Japan - is still comfortably ahead of China, the difference is much smaller than most Westerners might assume.

This may provide an indication that the actual standard of living for ordinary citizens in those different countries is not so very different, and may be rapidly converging.

Meanwhile, although the Western media often pairs China with India, the figure for that latter country is only about one-third as large.

Question 6: The Technological Edge

Does the US still have a technological edge over China?

Ron Unz Over the last couple of years American leaders have pointed to our huge lead in revolutionary AI systems as proof of our technological supremacy.

This AI boom has produced a multi-trillion-dollar rise in the stock market value of companies involved in this sector, with AI chip-maker Nvidia of Silicon Valley becoming the world's most valuable company, reaching a capitalization that topped $3.6 trillion.

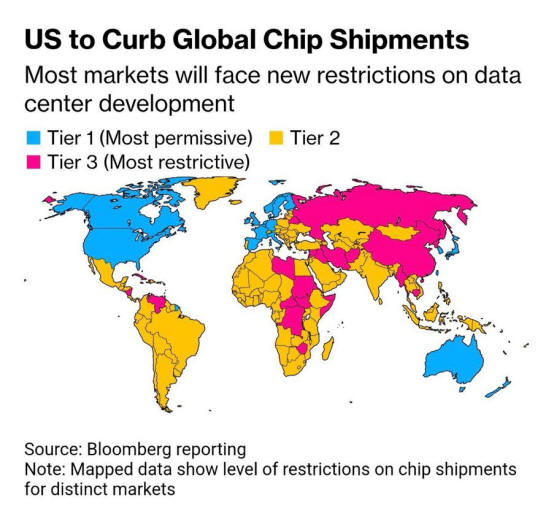

The Biden Administration sought to protect America's apparent lead through measures of doubtful international legality, violating our free trade agreements by banning the sale of cutting-edge AI chips to China while also strong-arming our allies into similarly preventing China from buying their top-tier chip-making equipment.

Hundreds of billions of dollars of investment capital flowed into AI startups such as OpenAI or the AI projects of leading tech corporations such as Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft.

An unprecedented building-boom for new data centers began, as well as a scramble for the necessary sources of energy to power them.

Although all of these AI projects were still losing money, often totaling many billions of dollars per year, they were considered proof that America would dominate the most important technologies of the future.

This continued under the incoming Trump Administration, with Trump holding a January 21st press conference with OpenAI and its top allies, boasting of their plans to invest a gargantuan $500 billion in a new AI project, grandiosely named Stargate.

But almost simultaneously with those bold words, that AI propaganda-bubble suddenly burst.

A small, totally unknown Chinese AI company called DeepSeek released a new AI system that was very comparable to the best of America's AI models, but built at tiny fraction of their cost. Once DeepSeek's effectiveness was confirmed, it became the #1 app downloaded on the Apple store, and also inspired days of front-page stories all across the world

Thus, even as Trump was bragging of his plans for a half-trillion-dollar investment in AI, a small Chinese firm had delivered an excellent AI system that only cost $5.6 million, a figure 99.999% lower, with that system created using only second-tier AI chips and far fewer of those.

Indeed, some people pointed out that the entire development cost of the DeepSeek AI was much less than the annual salary of many individual American AI experts.

The financial implications were obvious and within the next day or so a trillion dollars of the stock market value of AI-related American corporations evaporated.

Moreover, DeepSeek released its AI product as an open source system, allowing everyone in the world to examine and incorporate that code into their own AI projects.

Dozens of companies have already done this, severely challenging the entirely proprietary systems of America's reigning AI leaders.

A couple of your own articles from last week did an excellent job of describing this global technological earthquake:

This sudden, striking new development certainly reinforced the conclusions that Hua had reached in a number of his posts that I had heavily cited and excerpted in my own long analysis of the China/America competition.

Just as Hua believed that China was outperforming America economically, he felt that trends also favored China in the technological competition between the two countries and discussed these issues in a December post.

He analyzed the findings of ASPI, an Australian-based thinktank generally quite hostile to China, which had recently published its 2024 Critical Technology Tracker, an annual comparative analysis covering 64 different technologies in 8 meta categories, with the latter including:

Because this ASPI report tracked these same data categories back to 2003, it allowed the trends to be shown over time, and over the last twenty years these had shifted dramatically in China's favor.

The report also focused upon the potential monopolies in major technologies:

His post closed by noting that these technological advantages had direct commercial and military consequences:

In my November article on the underlying factors behind China's rise, I had sharply criticized Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, the 2024 winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, for their past claims that China had no hope of becoming a major technological innovator and would be permanently relegated to merely copying Western products.

Although I briefly noted a couple of the crucial technologies in which China now led the world, I had no idea that its lead had become so widespread across so many important categories, and I would have certainly cited this very comprehensive assessment if I'd had it available at the time.

Question 7: Is China a Communist Country?

People in the West typically disparage China as a "communist" country, but is that an accurate description?

In your article, you allude to the Confucian influence on Chinese society that emphasizes personal virtue and moral character aimed at ‘creating a harmonious society.'

Isn't Confucianism - which permeates the entire culture - more responsible for China's meteoric rise than communism?

Ron Unz Today's China is still ruled by a political organization that calls itself a "Communist Party," with its government paying lip service to that ideology and its past historic figures such as Marx, Engels, and Mao.

But the actual reality of China's economic and social system has evolved in a very different direction, and today's China bears almost no resemblance whatsoever to the classic Communist system of the Soviet Union or similar states.

Free enterprise of a very dynamic type is almost universal in China from top to bottom, ranging from the ubiquitous local village markets up to gigantic multi-billion-dollar private corporations listed on the different stock markets, including some of the world's largest real estate development conglomerates.

Although there is central government control of business activity, in some respects that control is less heavy-handed or intrusive than what is found in the United States or other Western countries that no one would ever call "Communist."

And aside from the U.S., China has the world's largest number of billionaires.

Obviously, a "Communist country" based upon widespread free enterprise and stock markets that contains huge numbers of billionaires is hardly a "Communist country" in the usual meaning of the term.

Thus, today's Chinese government fails to fit within the simple ideological framework of the old Cold War Era, and last year I happened to read an interesting book analyzing China's political system.

The author of The China Model was Daniel A. Bell, an American academic holding a Western-funded professorship at prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing, and his subtitle "Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy" explained the issues he discussed.

His book had originally appeared in 2015 with the paperback edition published the following year.

Although back then our countries were still on relatively friendly terms, the DC political elites were already beginning to view the growing economic power of China as a looming threat on the horizon.

This was indicated by the author's preface to the 2016 paperback edition, in which he expressed his surprise that his very restrained discussion of the Chinese political system had attracted such an unexpected outpouring of attention, much of it hostile and filled with claims that he had whitewashed a dictatorial regime.

Despite such angry reactions, Bell's main points seemed quite innocuous and even rather obvious to me.

He argued that in recent decades, the Chinese political system, certainly including its ruling Communist Party, had gradually shifted back to that country's old Confucianist traditions, with a strong emphasis on meritocracy as the major factor in advancement, including the important role of education and examinations.

Although patronage networks certainly played a role, especially at the very top, officials generally rose only if they had performed well at lower levels of government, with performance usually judged by economic growth.

As a result, Bell argued that the top leaders in China were unusually competent compared to their counterparts elsewhere in the world, notably including those in democratically-run countries.

He summarized the post-Mao system in China as tending towards "Democracy at the bottom, experimentation in the middle, and meritocracy at the top," a straightforward summary of his overall thesis.

China is certainly a one-party state ruled by the CCP - the Chinese Communist Party - but as a commenter recently suggested, a better description of those same initials might be "the Chinese Civilization Party" or even "the Chinese Confucianist Party."

In one of his earliest comments on our website, Hua Bin had suggested something very similar, emphasizing the role of the positive traits inculcated by the Confucianist thought that had traditionally played such a central role in Chinese culture:

Another fairly accurate if perhaps more controversial way of describing China's current system of government is that it amounts to national socialism, but without the extremely negative connotations implied by that term in today's West.

This ideological approach has become much stronger since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2013.

For example, as Hua explained:

Leading Western analysts have described President Xi's policies in very similar terms, though often with strongly negative implications.

For example, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd speaks fluent Mandarin and as a leading diplomat had followed China closely for decades, first encountering Xi more than 35 years ago, when both were very junior figures and privately meeting and speaking with him on numerous occasions since then.

A few years ago, he earned a Ph.D. at Oxford University with his doctoral dissertation being on the policies and world view of President Xi, and he recently published a very lengthy book entitled On Xi Jinping, incorporating much of that material.

In that work, Rudd argued that Xi has been moving China towards what the author calls "Marxist Nationalism," including,

Although this is probably somewhat exaggerated and the implications of such phrases are far too negative in the Western context, Rudd seems to be describing the same basic facts as those that Hua presents in a far more positive sense.

As I'd mentioned earlier, the tremendous and totally unexpected sudden success of China's DeepSeek AI system has hugely dominated the Western headlines over the last week or two, and some of the background to that technological triumph is quite intriguing.

For example, DeepSeek is actually a project of High-Flyer, a highly-successful Chinese hedge-fund that was founded in 2016 and manages some $8 billion of assets using AI systems.

But over the last several years, President Xi's Chinese government has exerted political pressure against companies focused on financial engineering, and this led CEO Liang Wenfeng to shift some of his effort away from the use of AI systems for trading towards the development of more advanced AI systems in general, with DeepSeek being the result.

As the New York Times explained:

Thus, according to the Western media, DeepSeek's huge global success seems directly attributable to the recent government policies emphasized by President Xi.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||