|

by NewsMediaOrganization

Illustration:

Detentions, public shaming and suicides intensify the country's corporate gloom...

But on September 22nd he made headlines for another reason.

His company, Shanghai-listed Great Microwave Technology, disclosed that Mr Yu had been taken away by China's anti-corruption agency.

The country's entrepreneurs must contend with a lengthening list of worries.

Foremost is the economy, which has never fully recovered from the 'pandemic'.

But a further set of concerns is growing in prominence.

As the economic outlook darkens, China's institutional shortcomings are making the business elite even more miserable. Official investigations into company leaders are on the rise. So are court rulings that limit their freedom to travel around the country.

A spate of suicides among bosses this year is widely seen as evidence of intensifying pressure.

It is now frequently directed at businesspeople too.

Changes to regulations in June allow agents to hold people for up to eight months, to reset the clock if a new crime is suspected and to interrogate prisoners endlessly.

Cells typically have no windows, lights are always on and detainees are often supervised 24 hours a day, even when using the toilet.

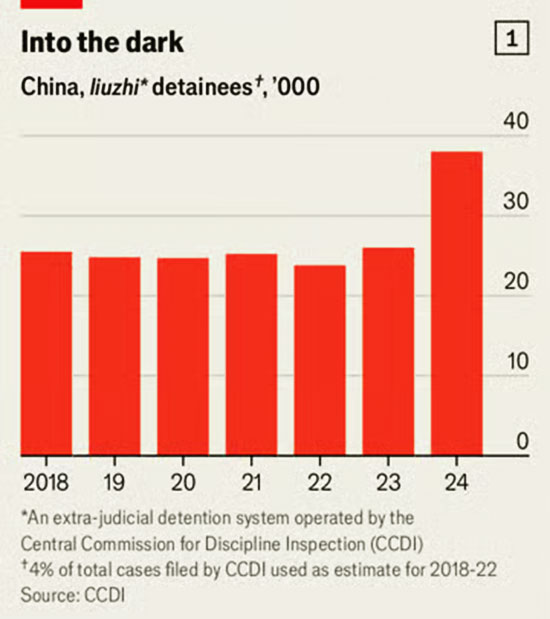

That already exceeds last year's record tally. But it is just a fraction of the broader picture.

Most corporate liuzhi targets work for unlisted companies, which are not obliged to explain to investors why their chief executives have disappeared.

The corporate side of the crackdown appears to be extensive.

The CCDI has said it took some form of disciplinary action (including liuzhi) against more than 60,000 people in the pharmaceutical sector and 17,000 in finance last year.

When an official is investigated, their entire business network can come under scrutiny, leading to a ballooning in corporate cases.

Some of the industries facing deepening anti-corruption probes, such as computing hardware and green technology, are tightly connected to local governments through procurement and contracting, notes Zhu Jiangnan of the University of Hong Kong.

Flagging economic growth may also help to account for the rise in detentions. Local governments are short on cash; many have enormous debts.

Some CCDI investigations have been characterized as "deep-sea fishing" expeditions, in which an executive is held on flimsy grounds in the hope that the harsh conditions of liuzhi will yield a confession of wrongdoing or the accusation of another wealthy person.

The investigators can then seize that person's (and their company's) assets.

A Chinese lawyer specializing in such cases says this is a sign that one local government is fishing in another's jurisdiction in search of funds. (The lawyer has asked to remain anonymous.)

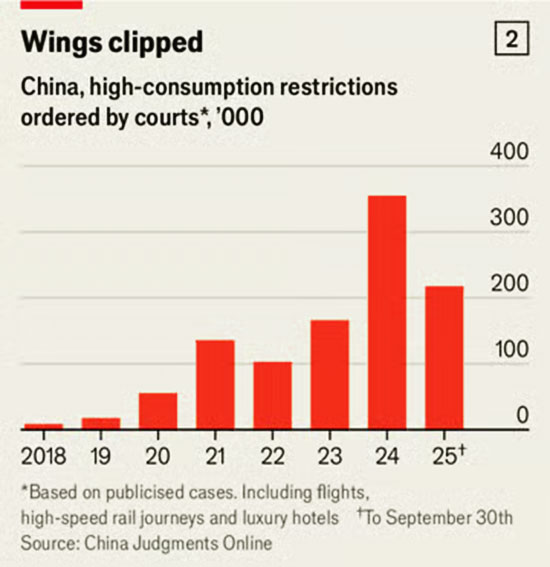

China's bankruptcy laws are not fully developed and courts often reach for quick fixes to put pressure on debtors to pay up. One method is to publicly add their names to the list, which bans them from "high consumption".

A court database shows that by the end of September some 200,000 people had been added this year, up from around 17,400 in the whole of 2019, before the economic rupture of the pandemic (see chart 2).

About 46% of this year's blacklistings were owing to contractual disputes, indicating that business-related activities led to the court rulings.

At a time when the economy is badly short of dynamism,

The central government has tried to improve conditions for entrepreneurs.

In February Mr Xi met a handful of China's top company bosses in the hope of signaling a reset.

But the dominant mood among entrepreneurs has instead stayed gloomy.

On September 28th it was revealed that Wang Jianlin, a property tycoon who was once China's richest man, had been added to the debtors' blacklist because of a contractual dispute.

This ban was lifted a day later but not without igniting a discussion on the dire situation facing some leading business figures. Mr Yu's detention has had a similar effect. If senior military scientists can be swept into liuzhi, no one is out of the corruption agency's reach.

Between April and July at least five prominent bosses leapt to their deaths from high buildings, leading to anguished public discussion about the burden on entrepreneurs.

The suicide of Wang Linpeng caused particular shock. The founder of a successful department-store chain, Wang was once the richest man in Hubei, his home province.

His suicide, days after his release, is just one of the few "that float to the surface", says the lawyer.

|